Image seeking in multilingual environments: a study of the user experience

Evgenia Vassilakaki

Department of Library Science & Information Systems, Technological

Educational Institute, Athens, Greece

Frances Johnson and R.J.Hartley

Department of Languages, Information & Communications, Manchester

Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK

Introduction

This paper explores the user experience when searching for images in a multilingual environment with the aim of identifying the core factors that underlie the users' actions and which may influence their behaviour. It does so using the experimental system FlickLing. There has been considerable interest in the development of multilingual information retrieval systems in recent years. Such systems are intended to accept queries in a single language and retrieve information objects held within the system regardless of the language of those objects. A common criticism is that there is little value in retrieving objects in multiple languages if the searcher is unable to understand text in the retrieved languages. It is reasonable to argue that no such objection can be raised when the objects retrieved are images which are inherently language independent (Sanderson and Clough 2002; Villena-Roman et al. 2005; Clough et al. 2005). Whilst the testing of multilingual information retrieval systems have progressed their development, there has been little exploration of how users behave when using such systems (Peters et al. 2012).

This paper seeks to contribute to multilingual information retrieval research by providing a detailed understanding of how one group of users behaved when retrieving images in a multilingual information retrieval environment. Focusing on eliciting users' rationales and justifications of their actions, it seeks to learn how users perceive, employ and adjust multilingual information retrieval systems to their needs and search strategies. Information seeking is known to be a highly interactive process and subject to a range of influences (Oard et al. 2000; Foster 2004). Therefore the aim of this study is capture user thoughts associated with their actions to provide insight into the possible influences on a user's search experience. We therefore study user information searching as the process of querying a collection to retrieve items of relevance to a given query but refer to studies of information seeking behaviour when the broader activity of seeking information in response to an information need is under consideration. The analysis of the data collected was based upon Straussian grounded theory to structure the theme according to the actions identified and the associated explanations given by users for these actions. Specifically, the data was analysed to identify:

- users' actions, interactions and thoughts while interacting with FlickLing;

- the similarities and differences in users' actions and interactions, as well as similarities and contradictions in users' explanations of their actions;

- the factors that influenced users' image searching behaviour in FlickLing.

The paper is structured as follows. A selection of the relevant literature is reviewed to place this user study in context and to demonstrate how it differs from other multilingual information retrieval research. The literature review is followed by a description of the research design and methods employed. The data analysis results in the description of the user experience which is presented as subject to the core influences identified. The final section concludes with discussion of the insights gained into the user experience.

Literature review

Multilingual information retrieval has emerged in the last twenty years as a research area focusing on the development of systems for the effective and efficient retrieval of information across languages (Oard and Dorr 1996). The evaluation of system performance helped progress multilingual information retrieval research, notably with the multilingual track introduced in TREC-3, the Text Retrieval Conference (co-sponsored by the National Institute of Standards and Technology and U.S. Department of Defence) which provided an infrastructure for evaluating text retrieval systems, and repeated as a formal track in TREC-4 (Harman, 1996). In 2000, the infrastructure for developing and evaluating information retrieval systems for European languages in monolingual and cross-language contexts was moved to the Cross Language Evaluation Forum programme with the test-suites for benchmarking extended to include collections in formats other than text such as photos, images, speech and video. The Forum is now known as the CLEF Initiative (Conference and Labs of the Evaluation Forum)).

Images are inherently language independent and thus image retrieval can often be seen as a language-independent task. This is not the case in concept-based image retrieval where the images are accompanied by descriptive searchable text. As a result, image retrieval integrates with multilingual information retrieval, as users' native languages can differ from the language used for describing images (Villena-Roman et al. 2005; Clough et al. 2005) and, as such, concept-based multilingual image retrieval has been studied in the context of the CLEF campaign (Petrelli and Clough 2005; Villena-Roman et al. 2005; Clough et al. 2006; Clough and Sanderson 2006; Olsson and Karlgren 2007; Cristea et al. 2009; Navarro et al. 2009; Müller et al. 2010).

System development for multilingual information retrieval has been well researched in these evaluation studies. More recently attention has been given to understanding the users and their use of the system. In the CLEF campaign from 2001 and onwards, user-centred studies were mainly produced in the context of the interactive CLEF (iCLEF) track which was launched in the same year. This was done to provide the necessary infrastructure and multilingual test collection for conducting studies that explore users' behaviour, mainly through questionnaires and search log analysis but occasionally through observation and interview. Whilst all methods may be used to collect user data, within iCLEF most researchers have used log file analysis and focused on the differences in users' characteristics (e.g., language skills) and on the use of the system.

Peinado et al. (2009) employed log file analysis to establish differences in behaviour among users with active and/or passive or no knowledge of the language of the target image. Karlgren (2008) analysed the log file to find evidence of different levels of users' confidence and competence. Vundavalli (2008) set out to explore the behaviour of the most and the least successful users to investigate the differences in users' search behaviour based on their language skills. Artiles et al. (2006) employed a questionnaire to examine the attitudes of users towards cross-language searching with the system in three search modes (no translation, automatic translation and assisted translation). Clough et al. (2006) used bilingual Arabic-English students during the development and evaluation phase of the Arabic interface for Flickr. During the development phase five users were observed and questioned about their actions and, during evaluation eleven were employed to carry out the iCLEF task. Ruiz and Chin (2009) recruited six North American students to explore the challenges users face when searching for images with multilingual annotations and how they behave to find the desired information.

This user study of multilingual information retrieval draws on qualitative data analysis of information searching behaviour to identify the key factors that emerge in the users' thoughts associated with their core actions. The use of qualitative methods in the study of information searching, such as observation, diaries, or think aloud, can be seen as allowing the user model of the system to emerge and to be studied in context. The study of information searching is predicated on the recognition that context informs behaviour, and that context in turn is defined by the meanings that people ascribed to the situations they find themselves in (an insight that derives in the main from symbolic interactionist sociology (Blumer 1956). Hence information searching behaviour will depend on the tasks associated with different domains and the problems associated with them.

Ingwersen's (1996) cognitive model, for example, views the users' perceptions of the work task as the trigger of the problem situation, leading to a variety of information needs to be integrated into the information seeking behaviour model (see Jarvelin 1986 and Bystrom and Jarvelin 1995). Whilst the emergent models cannot generalise towards a theory of information searching they can encompass the complexity of the interacting features and influences of the given context for a process that is non-sequential and iterative (Erdelez 1997; Cheuk 1998; Spink et al. 2002).

Foster's non-linear model of information seeking behaviour (2004), for example, depicts a non-linear process with users' characteristics, such as cognition, influencing the core processes of opening, orientation and consolidation. Our aim was to draw on the qualitative approach for conceptualising information searching in a multilingual environment and to make sense of the sources of its successes and failures from the user perspective. We do not aim to generate a theory of information searching behaviour but rather to contexualise the information searching actions and interactions in the multilingual information retrieval environment from the user perspective. In other words, we sought to describe the user experience and identify (rather than test) the factors that influence users' image searching behaviour in multilingual environments.

Research design and research methods

Our study adopts an analytical inductive approach with observation, retrospective thinking aloud, and interview. Coding principles proposed by Straussian grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin 1998) are used to identify actions and interactions, and to show users' reasons or justifications for every action; thus to explain and understand user information searching behaviour.

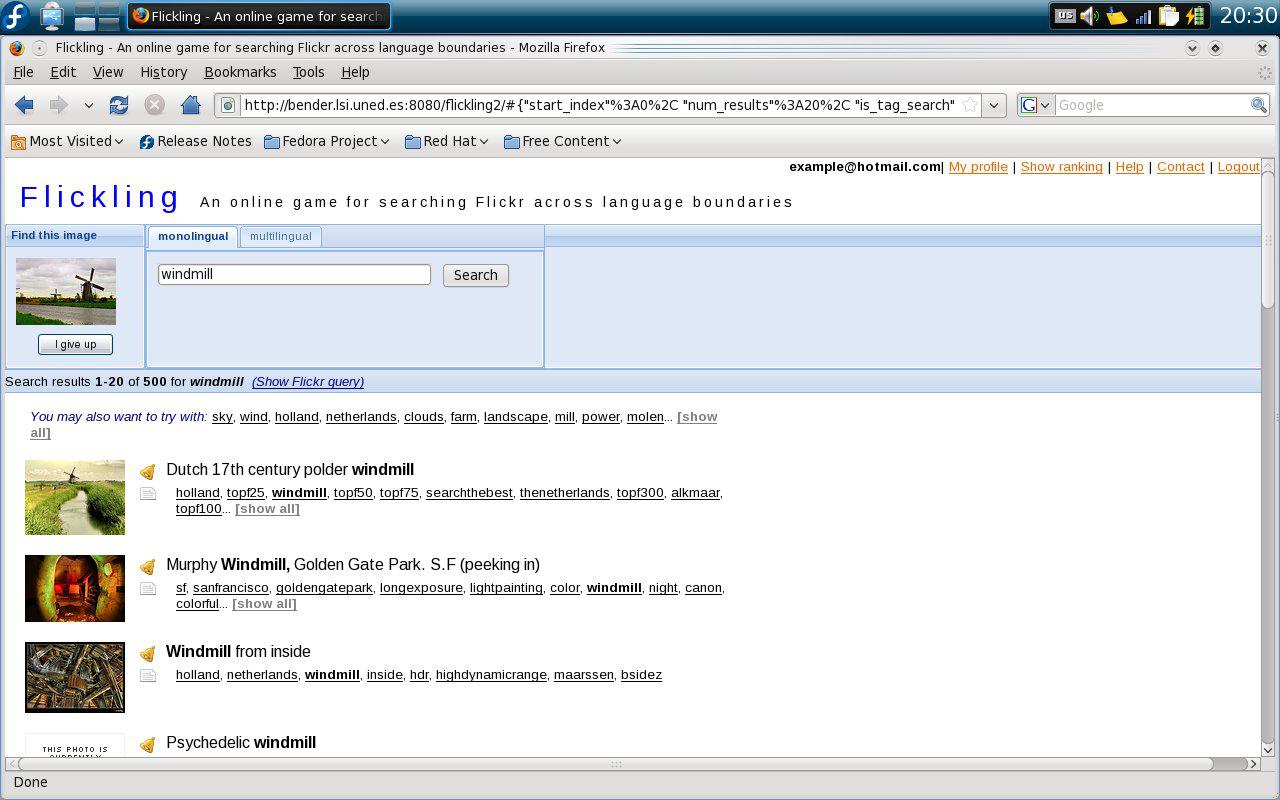

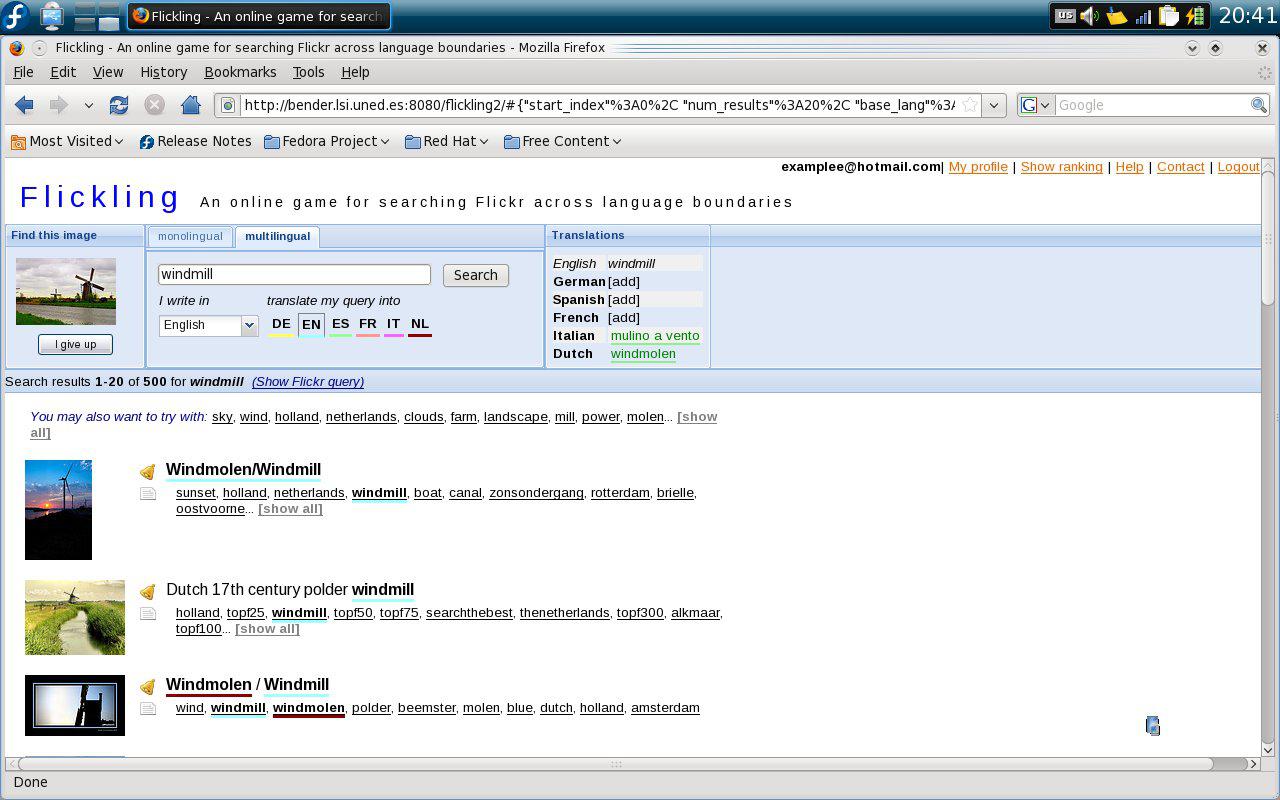

The research, which was undertaken in March and May 2009, used FlickLing, an experimental research tool based upon the well-known web image storage service, Flickr. FlickLing was developed as a part of the interactive Cross Language Evaluation Forum (iCLEF) and offers retrieval in six languages: Dutch, English, French, German, Italian and Spanish. It consists of two modes: the monolingual mode and the multilingual mode. The monolingual mode enables searchers to search in a single language, as illustrated by screen shots in Appendix 1, and retrieves only items tagged with terms in the search language. The multi-lingual mode uses the FlickLing translation function to retrieve any image that matches the search criteria regardless which of the six languages are used in its tagging, as illustrated in Appendix 2.

FlickLing was developed as a game in which users were challenged to use search terms to retrieve a known image that they were shown. This study required the users to search for three preselected images without knowing in which language those images were tagged. The chosen images each had a minimum of three tags, thus providing a reasonable number of access points. The images, tagged respectively in Dutch, German and Spanish, each contained at least one clue indicating the likely tagging language. Thus one contained an image of windmills which might be associated with the Netherlands, another image contained the German word Polizei whilst the final image was of carnival in Mexico. Searching was undertaken by twenty-four volunteer students (a mix of undergraduates and postgraduates), each of whom conducted the same three searches. No time limit was imposed on the searches although our participants were told that giving up on the search was permitted. Data were collected from seventy-two searches.

Users were observed whilst searching and key actions recorded on an observation sheet. This sheet was organised to enable the researcher to record actions and her thoughts whilst watching the search. This recorded matters of interest which were subsequently explored in post-search interviews. Users' interactions with FlickLing were captured using the screen capture software Camtasia Studio (v5.1). Post-search retrospective think aloud was used to explore with each user, their actions and thoughts whilst searching. Retrospective think aloud rather than concurrent thinking aloud was employed because this was believed to be less demanding on the users (Van den Haak et al. 2003). Immediately following the thinking aloud, brief interviews were undertaken in which the questions varied according to the observations made by the researcher during the searching.

The sampling strategy fell into theoretical sampling as defined in Straussian grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin 1998). As such, the sample was not pre-defined and no limitations were placed on users' characteristics. In the sample of twenty-four users, eighteen were female and six male ranging in age from 18 to 32; there was one over 32. Eleven were first year undergraduate students, five were second year undergraduate students and the remaining eight were postgraduate students, all of whom were studying at Manchester Metropolitan University.

In regards to users' knowledge of foreign languages, eight were monolingual, two bilingual and sixteen users stated knowledge of one or more foreign languages (including the two bilingual users who stated knowledge of additional foreign languages). The eight monolingual users were English native speakers. One bilingual stated Bengali and English and a basic knowledge of French and Spanish. The other stated Urdu and English, a good knowledge of French and a basic knowledge of German, Dutch, Italian and Spanish. The remaining fourteen users stated a range of language knowledge both in languages and levels as shown in Table 1.

| Language | Basic | Good | Very Good | Excellent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| German | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| French | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Italian | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Dutch | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Spanish | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

All twenty-four users stated having experience in searching for images. In particular, five searched for images very often, eight of them often, eight of them sometimes and the remaining three searched rarely. In addition, eight out of the twenty-four users had searched on the web for an image in a language other than their native language.

Data analysis

Users' image searching behaviour in FlickLing consisted of users' actions, interactions and reasons to reveal and describe their search strategies. We refer to users' own explanations and justifications of their actions while searching as 'conditions'. Based on Straussian grounded theory, three activities of open, axial, and selective coding were used in the identification of the actions/interactions and conditions resulting in the description of the user experience.

During open coding the text from the data gathering was opened up exposing the ideas, thoughts and meanings contained therein. The data were broken down into discrete parts and were closely compared for similarities or differences. The recordings of users' actions were coded to reflect users' image searching behaviour. Each of the twenty-four recordings was played back and users' actions were represented in the form of an action diagram, in sequence. Actions such as search terms used, various clicks on the interface's features (tags, suggestions, modes, give up, hints), the number of results retrieved and the number of pages scanned were recorded (for example see Table 2).

| User G1_01 |

|---|

| 1st Image |

| Monolingual Mode |

| ... |

| [typed] windmill holland |

| [clicked] search |

| 500 retrieved results |

| Scrolled down |

| ... |

The detailed transcripts created from retrospective think aloud were read through several times to form an idea of what sort of data were in the transcripts. Users' expressions that seemed important or had some significance to what they were doing were underlined. Key areas of interest were identified (e.g. modes usage, headings/tags usage) and relevant tables were created in an attempt to group these expressions under each user and for each image. These key areas formulated the concepts that were subsequently peer-reviewed for their consistency, clarity and agreement with the data. As a result, eleven concepts capturing and identifying users' actions and interactions with the interface's features while searching for images across languages were identified, as follows:

- modes usage;

- suggestions usage;

- headings and tags usage;

- hints usage;

- users clicking the 'give up' button;

- 'I write in language' feature usage;

- language button feature usage;

- paying attention to translations;

- system automatically retrieving translations;

- usage of language as a search term; and

- system playing around.

In the remainder of this paper we provide detailed analysis and illustration of the actions relating to three of these concepts, 1) Paying attention to translations, 2) Modes usage, 3) Suggestions usage, as well as a fourth action point at which the user stopped the search. We indicate how many of the users expressed a comment in Table 3. For example, in coding the concept Paying attention to translations during the first image search, 21 of the 24 users had comments and 11 of the 24 users had data in the retrospective think aloud that could be grouped as indicating the action Paid attention to translations: 7 Interacted with translations, 3 Clicked on translations, 7 Retyped the query, 2 Did not interact, and 10 Did not pay attention.

| Actions | Number of users expressing a comment | How many user comments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |

| Paying Attention to Translations | 21 | 21 | 20 | - Paid attention to translations

(11 users) – Interacted with translations (7 users) — Clicked on translations (3 users) — Retyped the translations (7 users) — Did not interact with translations (2 users) - Did not pay attention to translations (10 users) |

- Paid attention to translations

(18 users) – Interacted with translations (10 users) — Clicked on translations (4 users) — Retyped the translations (7 users) — Did not interact with translations (2 users) - Did not pay attention to translations (3 users) |

- Paid attention to translations

(16 users) – Interacted with translations (8 users) — Clicked on translations (4 users) — Retyped the translations (5 users) — Did not interact with translations (6 users) - Did not pay attention to translations (4 users) |

| Modes Usage | 24 | 24 | 24 | - Only one

mode (4 users) - Switched between the two Modes (20 users) |

- Only one

mode (4 users) - Switched between the two Modes (20 users) |

- Only one

mode (4 users) - Switched between the two Modes (20 users) |

| Suggestions Usage | 24 | 24 | 24 | - Suggestions not used (13 users) - Suggestions used (11 users) – Interacted with Suggestions (11 users) ---Clicked on Suggestions (6 users) ---Retyped the Suggestions (5 users) |

- Suggestions not used (18 users) - Suggestions used (6 users) – Interacted with Suggestions (6 users) --- Clicked on Suggestions (5 users) --- Retyped the Suggestions (1 user) |

- Suggestions not used (19 users) - Suggestions used (5 users) – Interacted with Suggestions ( 5 users) --- Clicked on Suggestions (3 users) --- Retyped the Suggestions (2 users) |

| Stopping the search | 24 | 16 | 11 | -Problems of identifying search

terms (7 users) -Unsatisfied retrieved results (14 users) -Failure to understand how FlickLing worked (6 users) |

-Problems of identifying search

terms (7 users) -Unsatisfied retrieved results (9 users) -Failure to understand how FlickLing worked (4 users) |

-Problems of identifying search

terms (7 users) -Unsatisfied retrieved results (2 users) -Failure to understand how FlickLing worked (2 users) |

Axial coding attempts to answer questions such as how and why and in doing so relationships between concepts emerge. In axial coding, users' actions and interactions are related to the responses to events, and link, in an explanatory way, to the behaviour studied. In this study, users' actions and interactions were identified in the action diagrams created from the recordings. The conditions explaining users' actions/interactions were identified in the analysis of the transcripts from the retrospective think aloud. Specifically, users' explanations of every action and interaction for all three images were identified as conditions and placed in each user's diagram after each relevant action and interaction. (see Table 4).

| Axial coding | User G1_01 |

|---|---|

| [System feature] | 1st Image |

| [System feature] | Monolingual mode |

| ... | |

| Action/interaction | [typed] windmill holland |

| Condition | 'there was a search hint and then I thought, I will just linked Holland with windmills and thinking maybe that was the image' |

| Action/interaction | [clicked] search |

| Condition | 'there were lots of them and I was just trying to find, trying to be more specific, thinking' |

| Action/interaction | Scrolled down |

| ... |

The conditions were loosely coded so that they could be assigned to each of the eleven actions identified as well as to the additional concept code representing the point at which the user stopped their search. This is shown in Table 5 for one of the action concepts Paying attention to translations which refers to whether users did or did not pay attention to the translations shown in the multilingual mode, each time they conducted a search. Initially, all users' comments throughout the task referring to this concept were grouped separately for each image and then grouped by the sub-concept (paid attention to translation, did not pay attention to translations, interacted with translations, did not interact with translations, clicked on translations, retyped the translations) (see Table 5, Columns 1, 2 and 3). The axial coding which brings together action and interactions and conditions (users' justifications or reasons for these actions) begins to suggest how the conditions identified in the analysis might describe the user experience for a particular action/interaction concept.

| Grouping

of concept - 'Paying attention to translations' |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Image | 2nd Image | 3rd Image | Concept |

| —Paid attention to translations expectation, number of retrieved results, language hint, search translations, |

—Paid attention to translations expectation, number of retrieved results, language hint, search translations, confusing results, system's functionality, learn the language of a wording, check search terms. |

—Paid attention to translations expectation, number of retrieved results, language hint, search translations, confusing results, system's' functionality, learn the language of a wording, check search terms, language skills. |

—Paid attention to translations expectation, number of retrieved results, language hint, search translations, confusing results, system's functionality, learn the language of a wording, check search terms, language skills. |

| —Interacted with translations –Clicked on translations expectation, experiment. |

—Interacted with translations –Clicked on translations expectation, experiment, failure to understand system's functionality. |

—Interacted with translations –Clicked on translations expectation, experiment, failure to understand system's functionality. |

—Interacted with translations –Clicked on translations expectation, experiment, failure to understand system's functionality. |

| —Retyped the translations failure to understand system's functionality, image's language learned, normal search behaviour, impulse (not knowing why). |

—Retyped the translations failure to understand system's functionality, image's language learned, normal search behaviour, impulse (not knowing why), system's failure to automatically search the translation, users' interpretation of system's functionality. |

—Retyped the translations failure to understand system's functionality, image's language learned, normal search behaviour, impulse (not knowing why), system's failure to automatically search the translation, users' interpretation of system's functionality. |

—Retyped the translations failure to understand system's functionality, image's language learned, normal search behaviour, impulse (not knowing why), system's failure to automatically search the translation, users' interpretation of system's functionality |

| —Did not interact with

translations failure to understand system's functionality. |

—Did not interact with

translations failure to understand system's functionality. |

—Did not interact with

translations failure to understand system's functionality, users' reliance on system, trust system it brought the right results. |

—Did not interact with

translations failure to understand system's functionality, users' reliance on system, trust system it brought the right results |

| —Did not pay attention to

translations extent of attention, understanding of the task, focused on searching, expectation. |

—Did not pay attention to

translations extent of attention, understanding of the task, focused on searching, expectation, trust in FlickLing |

—Did not pay attention to

translations extent of attention, understanding of the task, focused on searching, expectation, trust in FlickLing |

—Did not pay attention to

translations extent of attention, understanding of the task, focused on searching, expectation, trust in FlickLing |

The final step of coding is selective coding (Strauss and Corbin 1998). During selective coding the data, which was broken down during open and axial coding, is reassembled and refined to provide insight into user experience. Specifically, the thoughts and explanations made by the twenty-four users when searching for images in a multilingual image environment and associated with each of the actions and interactions were grouped into four contextual factors knowledge of system, search experience, query domain and knowledge of language.

For example, using Paying attention to translations, the conditions shown in Table 5 in the column Concept were grouped by the four contextual factors (shown in Table 6) and used to provide the description of the user experience in the following section.

| Paying attention to translations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contextual Factors | Knowledge of language | Search experience | Query domain | Knowledge of system |

| User conditions | learn the language of the

wording, language hint, language skills, search translations |

expectation, number of retrieved results, search translations, experiment, expectation, normal search behaviour, impulse, focused on search |

number of retrieved results, confusing results, check search terms, understanding of the task, extent of attention paid |

system's functionality, experiment, failure to understand system's functionality, users' interpretation of system's functionality, users' reliance on system, trust system it brought the right results |

Descriptions of the user experience

The analysis of the data collected through open, axial and selective coding led to the categorising of the user reasons and explanations (as conditions) relating to four contextual factors of knowledge of language, search experience, query domain and knowledge of system. These were seen across the user action and interaction codes and provide the basis for the description of user experience. We select three core actions paying attention to translations, modes usage and suggestions usage as well as the outcome concept stopping the search to describe the user experience through each of the four prevalent contextual factors.

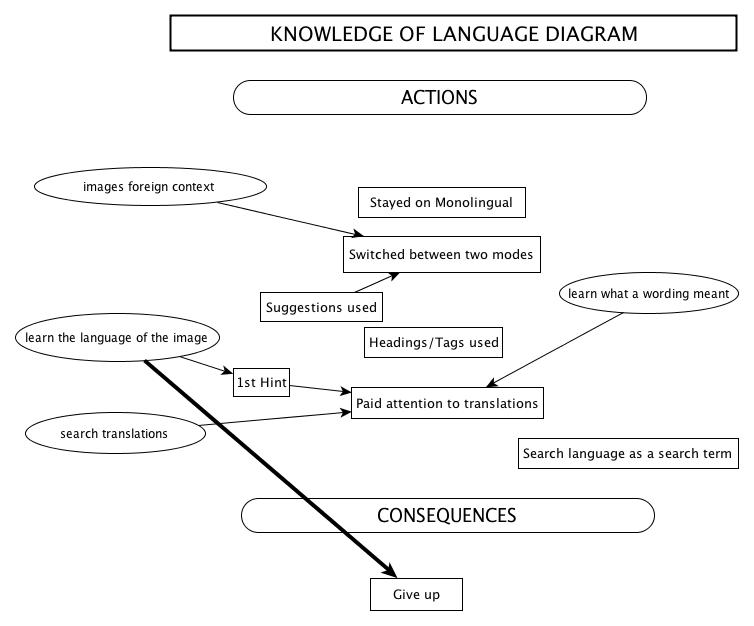

Knowledge of language

It was often the case that users' knowledge of language was given as a reason behind actions. Users with no knowledge of languages felt they needed to know foreign languages either to provide translations or to find translations. Some explained that they would not use the multilingual mode as they lacked knowledge of a foreign language. Others thought that it was difficult to search across languages and tried to find out what the translations meant by searching on the given translations. Users gave up on the search thinking that knowledge of the language was key to succeeding in the search. The influence of language as a factor can be seen in more detail when specifically relating to each of the three illustrative actions and outcome concept.

Modes usage

Once logged in, users started interacting with the system and one of their first actions was to choose between the multilingual and monolingual modes to start searching. Users' knowledge of language came into the thoughts that were associated with this action. In particular, users with low confidence in their languages skills stayed on monolingual mode:

I didn't know what else to write or what I should do, because I didn't know any languages and things like searching in other languages.

Others stayed in the monolingual mode, thinking that it was used for multilingual searching by users with a knowledge of foreign languages:

I thought I wouldn't be able to understand with the languages anyway so, I didn't click on it [multilingual mode].

In contrast, those with high confidence in language skills used both modes:

I would search first with my native language 'cause it seemed well… I don't know maybe I would try Italian to see because it is a language that I know and then I finally realised what I was supposed to be doing, it makes you search by using other languages and you are gaining confidence if you are speaking other languages.

Paying attention to translations

Each time a user conducted a search, translations were shown and the system automatically translated and retrieved images tagged with the translated terms. Users unable to judge the accuracy of the translations had to trust that FlickLing had provided the right translations:

the translations are there, if I knew Spanish I could check… but I can't so.…

Suggestions usage

When first confronted with the given images users tried to identify the key aspects of the images and to find the right search terms. Users who made use of suggestions (and headings or tags) perceived them as helpful when working on this task in other languages:

just to see whether it came up with any other suggestions as well as like the different languages… they were quite useful actually because they would also come up with the translations in other languages… if I would go back and recognized them I would clicked on them and look to see what it translated.

Users expressed reasons for ceasing a search

Users gave up on the search, at a loss for what to do next, when they did not know the language with which the given images were annotated and thought that knowledge of the language was key to succeeding in the search:

I needed to know Dutch, that further complicated the things in my mind… because if it is in Dutch it will be likely to be in the language Dutch but I don't know Dutch

Search experience

Users' reasons, thoughts and explanations frequently related to their search experience or how they perceived the search in hand. Statements were often made with respect to how the user normally searches or how they might want to control or direct the search itself. The users would mention the strategies they used when faced with too many or too few results. Previous experience, results relevancy, help and expectation were all related to what the users had to say about their search experience when explaining their actions on searching with FlickLing. Search experience as a contextual factor for the user conditions is shown again for each of the selected actions and interactions.

Modes usage

Users' search experience, and possibly the habits they formed when using other systems, was offered as reasons for clicking between the two modes. Users who clicked between modes explained that this is what they usually do when they search and decide what to do:

I was just trying to get a feel of the search engine. Before I actually like started probably searching for it.

Paying attention to translations

Some users clicked on the translations, explaining that this is what they usually do when searching, and expected the system to put the translations in the search box automatically:

I thought it might put it in the search.

Suggestions usage

Users gave reasons for using suggestions that related to conduct of the search. They were thought to help quickly find the images:

I thought of them easier to type them in, so, it was quicker to click on that and add it in my search.

or could be used to control the search:

I wanted to kind of narrow it myself the search results.

or use the suggested terms in conjunction with other search terms:

I still wanted to use it in conjunction with a couple of the words that I had already used and not just by itself.

Users expressed reasons for ceasing a search

Users' reasons for stopping touched upon their ability to develop or progress the search especially after several unsuccessful attempts:

I have exhausted all the keywords that I could think of and I couldn't think of anything else to put in.

Not knowing what else to do, users would give up since their previous experience in FlickLing had not been successful:

I just thought, I just because of the past experiences I just thought it's not happening but it's not brought me results so.

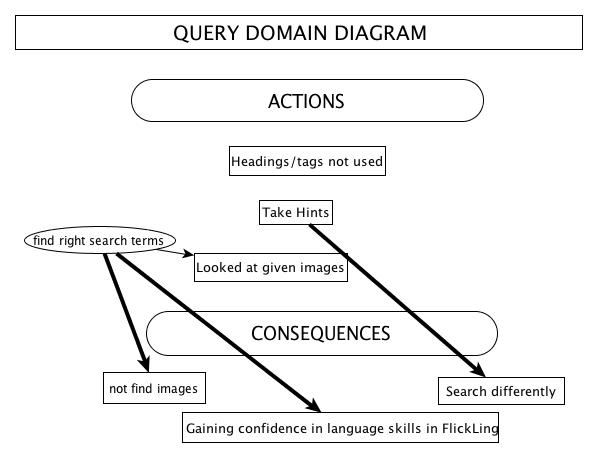

Query domain

Less was said about the query terms than might have been expected and, in the main, related to the actions of Suggestions usage and Modes usage. Relevancy of the search results was mentioned as well as how useful and helpful the terms were perceived to be.

Mode usage

The foreign context clues found in the image (or in the suggestions) and used to come up with appropriate query terms was often the trigger for users to switch between modes:

I think that this one was easier because you had like some clue like 'polizei' … I think because it had like on the boat it actually had a word in a different language so, that kind of triggered like that it must be that I have to search for a different language.

Paying attention to translations

The use of the translations was not without misconception. Those who retyped the translations wanted to check the translations of their search terms and use the translations as search terms:

I was trying to translate here 'skull'.

Suggestions usage

Suggestions that were perceived as relevant to the given images were considered to be useful and helpful in providing ideas of which search terms to use and to narrow the results:

I found them useful, they gave me ideas of what else to search.

Users expressed reasons for ceasing a search

Issues relating to the difficulty of finding a good query term to describe the sought images were given as reasons for stopping the search:

I didn't really know what was like, how to describe it so as to get the actual image.

I thought I just couldn't find the right because I thought it might need something more specific or broader keywords.

I didn't really wanted to type in just 'skull'… because I knew that will be a lot of 'skull' will be coming up.

Knowledge of system

Throughout the coding of the core actions, users' reasons and thoughts related to the contextual factor knowledge of system where the user was trying to determine how the system worked or when their actions were influenced by how they thought the system functioned. In general, users admitted to playing around with FlickLing while searching; that is to say, they experimented with it to see what it would retrieve and to 'get a feel of the system'. Regardless of whether the images were found or not, users were confused about how the system functioned and thought that translations were not shown and thus were not working. As with the other contextual factors, a range of aspects were mentioned relating to knowledge of system including, expectation, trust, experiment, time and understanding. The influence of system knowledge as a factor can be seen in more detail when the three illustrative actions and outcome concept are considered.

Mode usage

Choice of a specific mode (multilingual or monolingual) was determined by users' knowledge of the system and their interpretation of the two modes. Users who did not observe the system closely interpreted the monolingual mode as being the basic search interface:

I just thought I would stick to the basic one [monolingual mode].In contrast, users who paid attention to how FlickLing operated understood that the monolingual mode was for searching only in English and multilingual mode was for searching across the six languages. These users stayed on the multilingual mode offering the correct reason for this in terms of the system's functionality:

Well on monolingual I could only type in English obviously and in multilingual I could search for it in different languages and I would also get different searches.

Paying attention to translations

The users who paid attention to the translations attempted to understand how FlickLing worked or drew on their knowledge of the system to explain how the translations could be used:

I thought that maybe this translation just suggests what words you can use and then you type them in to the search box.

In contrast, users who did not interact with translations either did not understand the translation mechanism's functionality or relied upon and trusted the mechanism to give the right translations:

you typed in whatever you think the image is of and then it does everything for you… I thought it was doing it all for me.

In addition, some users searched the language of the image thinking it was a search term. When justifying this action, users claimed they were trying it out or thought that it would make their search more descriptive and would retrieve relevant results by narrowing the search down to one language:

I was getting a little bit confused thinking, did it translate it and expect you to type the translated words into the search box? I was trying to figure out how it works.

Suggestions usage.

Further reasons associated with the use of suggestions were, as one user stated, 'so as to figure out the mechanism'. When users were seen to re-type the suggestions in the search box it was revealed that they were uncertain of how the system functioned:

I wasn't sure whether I clicked on them whether it would search for them.

or, as they gained experience in FlickLing, suggestions were used only when they did not know what to try next:

I would use these taggy little things if they gave me any more information or ideas on this cause to be honest I couldn't really think of what to search for.

Users expressed reasons for ceasing a search

Users identified a series of problems relating to their understanding of how the system functioned in terms of hindering or preventing them from finding the given images. On giving up the search, users indicated that they had not really understood how the system was working, in particular with regards to the translation mechanism. Users did not understand that there were translations or why no translations were shown or why translations were not working:

because I didn't understand at this point that it can translate some of the words.

I was just wondering whether, a lot of the stuff was in English so, I was thinking, Is it searching properly?

For then it didn't give, if we got the translations from there it didn't had, it doesn't put it back the English one.

In addition, users were confused about how the system functioned and thought that they had used it incorrectly because they did not understand it:

I didn't really understand what it was happening when I clicked on these words [language buttons] whether they were crossed out or I wasn't sure.

Users were seen to completely give up, not knowing what to do next; they put this down to not understanding how FlickLing was working and thus how to search in FlickLing:

I wasn't really sure of what else to do.

User experience insights: discussion and conclusion

Qualitative techniques of observation, retrospective thinking aloud, and interview were used to collect user data whilst interacting with the FlickLing multilingual information retrieval system. The coding of the transcripts and the users' video sessions followed the principles of grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin, 1998). This contributed to our understanding of users' search behaviour in multilingual contexts and in particular it revealed the complexity of this behaviour as well as the specific factors that impose in some way on users' search experiences.

The progressive grouping of the concepts, sub-concepts, codes and sub-codes enabled the identification of the key actions and interactions and of the associated reasons and thoughts, grouped into four contextual factors. It is important to stress that the aim was to analyse the user experience with respect to the actions and conditions of the entire group of participants in the study. There is no attempt to generalise and suggest that this represents the behaviour of the majority of users; rather the aim is to show the variety and the complexity of users' behaviour while searching in multilingual environments. In this paper we have described the user experience, the reasons behind their actions, and their perception of the interactions, through each of these four contextual factors for the selected action codes of modes usage, suggestions usage, paying attention to translations, as well as stopping a search. The four contextual factors knowledge of language, query domain, search experience and knowledge of system were taken to be significant in the sense that user comments (reasons or thoughts) all related to one or more of these factors and could be seen to occur throughout the various actions and interactions.

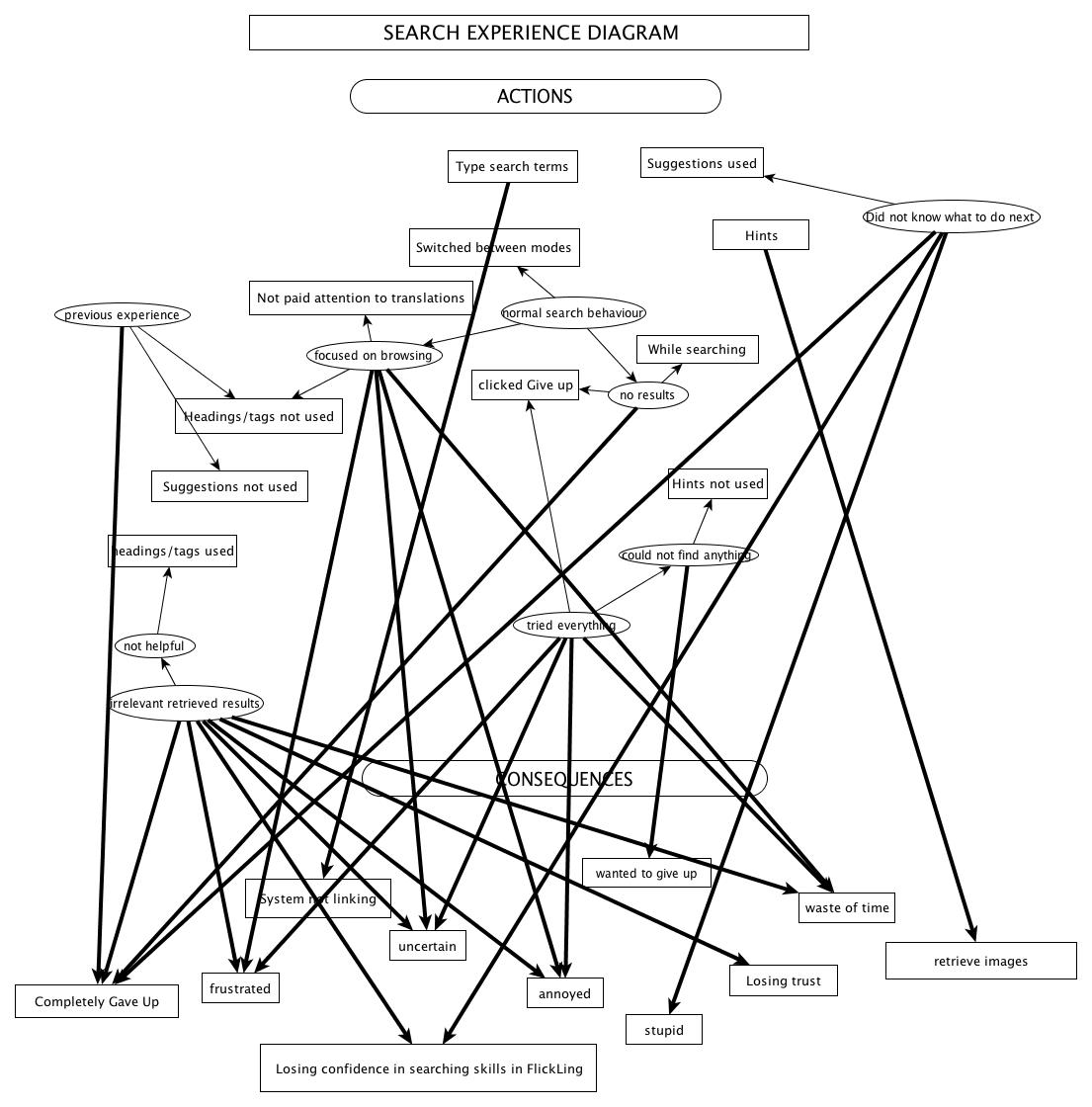

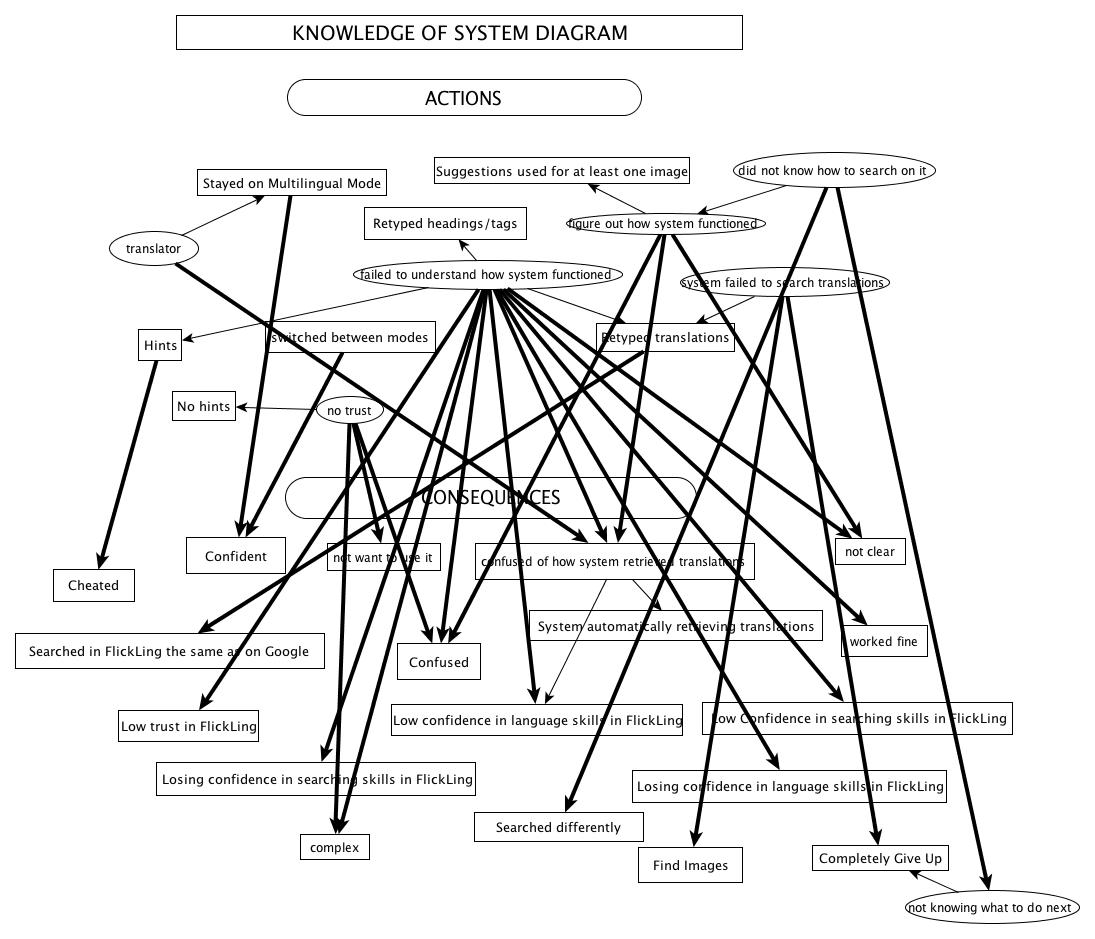

Whilst this may suggest a modelling of behaviour according to these four factors at the specific interactions during a single search using FlickLing, the actual picture of information seeking is a complex one. In an attempt to illustrate this, four diagrams were used, one for each conceptual category, in which each code and sub-code of the significant actions along with the conditions (being the users' justifications) identified as belonging to the category of the diagram. The diagrams for knowledge of language, query domain, search experience and knowledge of system are given in Appendix 2. The arrows used in the diagram simply indicate a relationship among and between the actions and conditions codes, and served to demonstrate during the analysis that conditions when identified and grouped by the four contextual factors could be seen to be prevalent across the actions and interactions of the search. This is not to generalise and suggest that all four factors will influence the user and their interaction during any one search; rather the picture gained is that at any point in the search any one or any combination of these factors may impact on and thus describe the search in the user's experience.

This study has identified, perhaps not surprisingly, users' knowledge of language as an important factor in their behaviour in a multi-lingual image retrieval environment. Beyond this, however, the users' unfolding experience was also influenced by their lack of experience in searching online for images, their ability to find (or failure to find) the right search terms when searching for images, and their knowledge and experience of the system. Whilst we would welcome further research which affirmed our findings, this research may offer some insight into the complex relations held between user factors and with use of the system. For instance, studies of search in multilingual information retrieval systems report on a variety of findings specific to the particular investigation. Artilles et al. (2006) reported that their users had a preference for an assisted translation mode. Similarly Vunadivalli (2008) noted that users tended to switch to the multilingual mode once they had discovered that it was more useful. In our study participants did not profess a preference for one search mode over the other but gave reasons associated with the four contextual factors for use of a particular mode or when switching between them.

There is contradictory advice in other studies given on the matter of allowing users to change the translations offered by a multilingual information retrieval system. Davis and Ogden (1997) stated that users would be able to judge erroneous translations and Petrelli and colleagues (Petrelli and Clough 2005; Petrelli et al. 2004) have argued that it is mandatory that users are permitted to check and if necessary change a translation. Evidence from Cristea et al. (2009) suggests that users are prepared to do this. During the retrospective thinking aloud, our participants commented on the accuracy of the translations with reference to their own language skills. That is they indicated that they could not judge the translations as correct, or that that they had to assume they had been accurate on the basis of the images retrieved. As our users either felt that the system would do everything for them or were not clear about how to use translations, we are in closer agreement with Figuerola et al. (2004) who noted changing translations was of little interest to their users. It is clear that different studies have yielded contradictory results concerning the translation functionality in multilingual information retrieval systems.

Whilst we recognise that a partial explanation is doubtless the different ways in which the studies were conducted, we also suggest that this very contradiction serves to emphasise the importance of system developers making clear their system's functionality. The four contextual factors that emerged from the detailed observation of the use of a multilingual information retrieval system may provide a basis for understanding how the system features (such as translations and suggestions) may be useful to the user during a search. The importance of each of the four contextual factors in this respect is perhaps highlighted in a final comparison of studies performed using FlickLing. Ruiz and Chin (2009) reported that difficulty in finding the correct search term and in selecting the correct translation lead users to stop an unsuccessful search. In our study on Flickling users also stopped the search when they failed to find the relevant images due to a poor understanding of the system. The analysis of the qualitative data obtained from studies to investigate user experience, as presented here, is time consuming and lacks testing for generalisation. The data that the investigation yielded may provide insight useful in the user centred design of multilingual information retrieval systems.

About the authors

Evgenia Vassilakaki is a Scientific Associate at Technological Educational Institute, Athens. She received her PhD from Manchester

Metropolitan University, Department of Information & Communications. She can be contacted at: EveVasilak@gmail.com

Frances Johnson is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Languages, Information & Communications at Manchester Metropolitan University She has PhD from the University of Manchester in Computational Linguistics and her research work focuses on the design of the search interface and the study of information interactions. She can be contacted at: f.johnson@mmu.ac.uk

R.J. Hartley is Emeritus Professor in Information Science at Manchester Metropolitan University and researches scholarly communication and information seeking behaviour. He can be contacted at: r.j.hartley@mmu.ac.uk