Poster session

Pathways to research participant recruitment in a challenging information behaviour context: South African cold case investigators as exemplar

Naailah Parbhoo-Ebrahim and Ina Fourie.

Introduction. Research participant recruitment is challenging – especially in vulnerable, stigmatised, high security, poorly demarcated contexts and contexts with diverse and interchangeable job labelling and poorly centralised reporting infrastructures. Cold case investigators in South Africa is an example of the latter.

Method. Scoping literature review of information behaviour and other disciplines to note challenges and solutions in research participant recruitment.

Analysis. Brief review of challenges noted in research methodology textbooks and applied thematic analysis mapped to problems and correlating solutions for research participant recruitment (various disciplines including information behaviour).

Results. There are many challenges and solutions noted across disciplines including information behaviour e.g. job confidentiality, poor context demarcation, diverse and interchangeable job labels for the same context. Solutions reported include exploring related job/role labels, snowball sampling, non-intrusive social media methods.

Conclusion. Based on experience with information search heuristics we suggest an additional novel approach for information behaviour research (and other) participant recruitment; a South African cold case investigator information behaviour study serves as exemplar to demonstrate how search heuristics can be used to identify potential research participants and solicit referrals for research participant recruitment.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2026

Introduction and background

In order to conduct successful, high quality research it is vital to identify context appropriate research participants, select and recruit them. A research participant is an individual who agrees to participate in the research process through e.g., questionnaires, interviews, experiments, personal health records, narratives, focus groups, and direct observation (Case and Given, 2016; Given, 2008). Participants may also be referred to as research subjects in policy documents, research ethic guidelines and institutions (Given, 2015). For this paper we will use the term research participant.

Although some disciplines have specific guidelines and criteria, they seldom fully address the challenges of actual identification and recruitment (Aidley, 2019; Hackett, 2016; Pickard, 2013; Symon and Cassell, 2012; Rubin and Babbie, 2008). Researchers need to consider the criteria needed for ethical research participant selection, requirements, retainment and research conduct (Begun, et al., 2018; Singh, 2008). They must also reckon with the challenges of the context in which a study is conducted. Some contexts such as palliative care, caregiving, minority group or non-dominant culture contexts, intimate partner violence, law enforcement, youth and stigmatised diseases involve additional challenges such as vulnerability, stigmatisation, high security, poor context demarcation, interchangeable job labelling and poorly centralised reporting infrastructures (Koziol-McLain, et al., 2016; Moscovitch, et al., 2015; Mertens and McLaughlin, 2004). Information behaviour studies are no exception to challenges in research participant recruitment (Burford and Park, 2014; Case, 2012; Fisher, et al., 2006; Cooper, et al., 2004).

Researchers in law enforcement and cold case investigations face additional challenges since in some sections of law enforcement, such as cold case investigation, there are fewer people that meet the precise selection criteria of a study. Davis, et al. (2011) define cold case investigations as homicide cases that could not be solved due to the lack of evidence, DNA forensic technology and witnesses at the time of the crime being committed. These cases may be left unsolved for months or years until advancements in technology, DNA matches are made, and eyewitnesses or suspects come forward (Walton, 2014). Cold case investigators are homicide detectives who investigate cases that have gone cold (Rapp, 2005). Their official titles include police detectives, homicide detectives, cold case detectives and homicide investigators; they all complete the same tasks to solve cold cases (Roufa, 2017). In cold case investigations potential research participants are also incarcerated, refuse to participate or have passed away (Govender, 2017; Yaksic, 2015). Neal (2004), reporting on the information behaviour of police officers did, however, not dwell on challenges with research participant recruitment; this can be ascribed to the fact that the environment from where research participants were recruited was accessible and well demarcated.

- A scoping review of the literature to identify challenges and solutions.

- Inductive reasoning drawing on prior experiences e.g. in literature searching and search heuristics to identify means to extend conventional methods of research participant recruitment and snowball sampling.

Significance and relevance of topic

Promising research should not be abandoned due to challenges and barriers or stumbling blocks; solutions must be sought. Many such contexts have been noted in the Introduction. Many researchers experience issues with recruiting research participants that meet the criteria of a specific study. By using an information behaviour study of cold case investigators (already shown as worth further investigation [Parbhoo-Ebrahim and Fourie, 2018]) as example, this paper intends to draw on challenges and solutions reported in research textbooks, as well as in a variety of disciplines and more specifically in information behaviour research to offer suggestions to information behaviour studies in challenging contexts. In addition, the suggestions will inform the information behaviour study with cold case investigators as set out in Parbhoo-Ebrahim and Fourie (2018).

Research question and sub-questions

>Which innovative methods can be applied to recruit hard to identify research participants for information behaviour studies – South African cold case investigators as exemplar?

RQ1: What challenges have been reported on hard to recruit research participants?

RQ2: What solutions have been reported on hard to recruit research participants?

RQ3: Which innovative methods can be used to supplement existing solutions to recruit research participants for an information behaviour study with hard to recruit research participants – South African cold case investigators as exemplar?

Method: scoping literature review, thematic analysis and inductive reasoning

This paper is based on a scoping literature review. Grant and Booth (2009, p. 101) define a scoping literature review as a ‘preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research)’. A scoping review does not adhere to the strict guidelines of systematic reviews and is much less comprehensive (Booth, et al., 2012). Details on the scoping review and selection of publications is set out in the section to follow.

We applied thematic analysis to the selected publications to identify (i) core challenges reported on research participant recruitment and (ii) solutions to research participant recruitment in various disciplines and contexts; where available we focused on law enforcement and cold case investigation. According to Braun and Clarke (2012, p. 57), thematic analysis ‘is a method for systematically identifying, organizing, and offering insight into patterns of meaning (themes) across a data set’. Thematic analysis is a form of qualitative analysis that is used to analyse classifications and present patterns that relate to the data (Alhojailan, 2012). Namey, et al., (2008) state that a thematic analysis provides researchers with the precise relationships between concepts and compare them with the replicated data.

The literature search and selection choices for the scoping review was done using the following:

Databases searched: Emerald Insight, IEEE Xplore® Digital Library, Web of Science, all Proquest databases to which the institutional library subscribes including Library and Information Science Abstracts (LISA), all EbscoHost databases to which the institutional library subscribes including, ERIC, Library & Information Science Source, Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts (LISTA), PubMed, Sabinet (a local database service), Sage Publications, ScienceDirect, Taylor & Francis (Journals), Wiley Online Library.

Concepts and search terms searched: research participants, human research subjects, research participants combined with the relevant fields e.g. cold case investigation and law enforcement, research participant recruitment (various contexts including specifically cold case and law enforcement were considered).

Literature selected for review: A total of 78 publications were analysed for this paper. Since this was only a scoping review, we were very selective (manual selection) to get to a manageable body of relevant literature: only publications in English, only if full-text was available and no limit on date published. Theses and dissertations were included. The articles reviewed included: cold case investigation studies per se: 10; information behaviour studies: 18 (information behaviour in various contexts: 10; information behaviour related to cold case investigation: 2; information behaviour related to law enforcement: 6); various contexts reporting research participant recruitment challenges: 19; research methods prone to challenges and solutions: 31 (articles: 9; research method textbooks: 21).

Some of the core research methodology textbooks consulted: Creswell (2014), Kumar (2014), Leedy and Ormrod (2013), Pickard (2013), Babbie (2012), Given (2008) and Federman, et al. (2002).

In addition, we decided to draw on the prior experience of the second author to identify additional means to find institutions and people who can either participate or offer referrals to institutions or people. We applied inductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning begins with specific observation to broader generalisations and theories (Trochim, et al., 2014). It is also referred to as the bottom-up approach where a researcher will begin with detailed observations and measures, distinguish patterns and regularities, formulate tentative hypotheses that can be explored and develop general conclusions or theories (Trochim, et al., 2014). Our application of inductive reasoning did not apply to research data, but experiences and knowledge of the literature on information literacy, online searching and specifically search strategies and search heuristics (Bothma, et al., 2017; Savolainen, 2016; Ruthven, 2010; Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005; Harter, 1986). Bates’ (1989) work on berrypicking techniques and a diversity of search strategies especially served as inspiration. This was supplemented with insights on a practical level from Bothma, et al., (2017) while Ingwersen and Järvelin (2005) alerted us to the numerous underlying challenges in successful information retrieval – choice of vocabulary and various points of entry e.g. subjects as well as authors and bearing in mind the frame of reference (cognitive spaces) of those generating records in information retrieval sources as well as those generating documents. Work by these authors encouraged us to search wider and to work from different angles to identify points of entrance such as institutions for referrals as well as opening up active participant recruitment. In addition, work by Savolainen (2007, 2016) offered encouragement to look beyond the obvious for different information sources (i.e., to explore and redefine information horizons), and to move beyond deliberate strategies starting the search process with initial intentions e.g., identifying cold case investigators as research participants. In his research Savolainen (2016) found also emergent strategies that ‘indicate how patterns in information seeking and searching developed in the absence of intentions, or despite them’. One of the most valuable characteristics of information searching, is the iterative nature and ability to adapt and explore new approaches. Apart from the sources acknowledged here the second author draw on her own experiences in search heuristics from teaching information retrieval, information literacy and literature reviews. The concept of search heuristics and how we applied it is explained in the section Applying search heuristics to find solutions.

Findings from thematic analysis

Textbooks on research methods often provide detail on the methods to be followed for research participant sampling and recruitment (Babbie, 2012; Creswell, 2014; Leedy and Ormrod, 2013; Pickard, 2013), but with limited advice on dealing with challenges. They focus on appropriate sampling techniques, sampling ratios and adherence to ethical research conduct including applying for and receiving ethical clearance, obtaining employers’ permission to conduct the research, obtaining informed research participant consent, treating research participants with respect and protecting their privacy and confidentiality, as well as ensuring that research participants do not come into harm physically and emotionally (Aidley, 2019; Pickard, 2013; Bryman, 2012). Even many research articles would only state that challenges were experienced and that is why they have a smaller number of research participants than expected, but without going into detail of how they resolved such challenges.

From our analysis of the literature sources we identified 5 themes for challenges experienced that are specifically relevant to the case we use as exemplar (i.e., an information behaviour study of cold case investigators in South Africa) and 5 themes for solutions to address challenges with research participant recruitment. For both the challenges and solutions we will very briefly note general issues and suggestions, before focusing on the themes relevant to context similar to our exemplar.

Themes for challenges

Many challenges apply in general when recruiting research participants and only a few are more specific to contexts such as cold case investigation and law enforcement in general. General concerns include issues of privacy and confidentiality and reluctance to participate due to lack of time (e.g., too many work priorities), lack of understanding of the project and how research participants will benefit (Surmiak, 2018; Pickard, 2013; Couper, et al., 2008; Pérez-Cárceles, et al., 2005). The latter relate to lack of motivation especially when no incentives are offered (Zutlevics, 2016). Sometimes research participants may be in a hard to reach physical location, it may be difficult to trace their contact detail and physical addresses, employers might be unwilling to give permission and research participants might not have access to appropriate technology such as devices and Internet connections for virtual meetings (Bender, et al., 2017; Watson, et al., 2016). Some researchers find it difficult to determine who they should actually recruit as research participants; this relates to a clear demarcation of the research problem, the context and the people to involve in searching for answers (Morris, 2018; Hennink, et al., 2011). Sometimes the potential pool of research participants is much smaller than expected (Grove, et al., 2012). This would call for actions to expand the scope of the study e.g. considering different geographic regions or considering related fields; the latter will depend on the nature of the research problem and need to be done with great care (Morris, 2018). Research with deeply vulnerable, stigmatised communities and high security/risk communities faces serious challenges in gaining trust (Gemmill, et al., 2012). Many emotional experiences have also prevented people from participating: bashfulness, shame, suspicion, fear, scepticism and feelings of incompetence (Kubicek and Robles, 2016; Labott, et al., 2013). In information behaviour research challenges are especially experienced with deeply qualitative research methods and with research participant recruitment in research requiring people to communicate their experiences, absence of formal ethical review committees and privacy concerns associated with [online] tracking (Akanbi and Fourie, 2018; Wang and Yu, 2017; Smith, 2016; Wellstead, 2016). We selected the following themes from the scoping review for further discussion; these are all relevant to the case we use as exemplar:

- Lack of a dedicated unit or centralised body to give permission for a research study and to approve access to potential research participants and ways of recruitment: In the South African context, albeit many efforts, there is not a central unit for cold case investigation. Although the formation of a dedicated cold case team was announced in 2018 (Mitchley, 2018; Sicetsha, 2018, el), it has still not been established. It is thus difficult to determine where and how to apply for permission to recruit research participants through the institutional infrastructure and how to get entrance to recruit participants.

- Establishing contact with research participants: Although there are many examples of groups where it is easy to establish contact such as studies with students, hospital patients and staff working for a dedicated institution, in a challenging context such as cold case investigation, researchers might not be able to make contact with the relevant individuals without drawing on alternative strategies (Sitole, 2019; Seidman, 2006).

- Diverse labels for the job: A diversity of job labels and lack of consistency over various sectors make it challenging to identify research participants. In the South African context, various labels apply when considering a study with cold case investigatorsg. detectives, homicide detectives, private investigators, South African police services (SAPS) officers and South Africa's Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation (such as Hawks investigators) (Mitchley, 2018; Sicetsha, 2018).

- Too limited pool of potential research participants: sometimes challenges are aggravated if there is a limited number of people meeting with the criteria (Cleaver, 2017; Kubicek and Robles; 2016; Weierbach, et al., 2010). This would happen with a specialist or exclusive group. E.g. winners of a specific talent country competition in comparison with winners of a weekly national lottery. For our exemplar there might be many law enforcement officers and many detectives, but relatively few working on homicide cases that have gone cold. This raises challenges with regard to the demarcation of a project.

- Challenges with community entrance: Krauss (2014) explains community entrance as the understanding of the cultural context, fundamental values, emancipatory concepts and interests, and circumstances of people within a specific area before becoming a member of the community. In some contexts, it is necessary to first gain the trust of the community of research participants and to understand their cultural or workplace practices before being given permission to start with the research.

I experienced a number of difficulties during the community entry phases of participant- observation. Initially two key issues stood out, namely, the difficulties associated with intercultural communication and some ideological remnants associated with the Apartheid [former South African political regime] legacy (Krauss, 2014, p.130).

Various researchers have reported challenges in gaining the trust of a community or individual research participants (Joubert and Webber, 2020; Ford, 2015; Carter, 2013; Case, 2012; Cronin, et al., 2007; Meyers, et al., 2007; Patel, et al., 2003).

Themes for solutions

Many suggestions on research participant recruitment have been noted, but not always direly related to challenges experienced. Traditional methods such as press releases, advertisements in newspapers, the radio, television interviews and targeted mail (nowadays email) invitations to participate, as well as none or less intrusive methods such as flyers, posters and bulletin board tear-offs are widely reported. Even recruitment agencies (Raymond, et al., 2018; Watson, et al., 2018; Newington and Metcalfe, 2014). Gradually the shift moved to online recruiting: social media postings using Facebook and WhatsApp and postings on appropriate websites (Sharon, 2018; Bender, et al., 2017). Non-intrusive methods such as the analyses of question and answer websites and twitter feeds are especially good for sensitive topics. Westbrook (2014) made use of question and answer (Q&A) forums, such as wikianswers, Ask.com, Blurtit and Yahoo! Answers as a non-intrusive method. Although it initially was used as a method to avoid application for ethical clearance, several voices have raised arguments that some form of consent or informing posters must be addressed (Gelinas, et al., 2017). Searching social networking sites such as LinkedIn has also been useful (Sharon, 2018; Bender, et al., 2017; Gelinas, et al., 2017). Multi-pronged recruitment strategies such as combinations of traditional, web-based, and online survey methods (Watson, et al., 2018) have also been noted. A solution that has been noted is to increase the number of research participants that can meet the criteria of the research by identifying professionals or experts that can be contacted as entry point to research participants before implementing a snowball technique (Newington and Metcalfe, 2014). Snowball sampling, also known as peer to peer recruitment, is widely noted; the researcher makes contact with a few research participants and then invite them for references to other potential research participants (Morris, 2018). Although not essential it can be good to start with people known to the researcher. When implementing a snowballing technique, a researcher must find one or a few individuals that fit the criteria; these individuals may be people known to the researcher such as friends/family or other types of acquaintances (Maungwa and Fourie, 2018; Pajo, 2018).

From the scoping literature review, we selected the following themes for solutions since they relate best to the challenges experienced with the exemplar for cold case investigation.

- Recruitment strategies aligning with the contexts and characteristics of the research participants who need to be recruited (Rook, 2018; Kumar, 2014).

- Non-intrusive methods for recruiting (e.g. recruitment agencies, Twitter polls, Facebook posts) (Miller, et al., 2019; Raymond, et al., 2018) or for non-intrusive observation and analysis e.g. discussion boards and question and answer websites (such as wikianswers, Ask.com and Yahoo! Answers).

- Extending research participant criteria to draw on a larger pool of potential research participants. Guclu (2011) describes how information researchers extended studies on the information-seeking behaviour of professionals to go beyond professionals in the field of science and scholars to other professionals that included: doctors, engineers, nurses, lawyers, law enforcement officers and other occupations.

- Snowball sampling: Jacobs, et al. (2016) as well as Ju and Albertson (2018) recruited participants through a snowball sampling from law enforcement agencies, bereavement groups and media personnel; these participants gave referrals to the researcher to further pursue.

- Recruitment through social media site such as LinkedIn has also been reported (Sharon, 2018).

Since these themes do not fully address the themes for challenges for our exemplar. We thus turned to search heuristics for further solutions.

Applying search heuristics to find solutions

As explained under the Method section, we used inductive reasoning to come to the decision that the purposeful systematic application of search heuristics (i.e., targeted to our purpose and finding solutions to the challenges listed under themes for challenges), might enable us to identify appropriate research participants. Harter (1986, p.170) explains that ‘a search method or heuristic is a move made to advance a specific strategy’. According to Harter (1986, p.194):

Regardless of the search problem or the overall strategy that has been selected initially to solve it, the ongoing process of online searching is best regarded as a heuristic, problem-solving activity, analogous to scientific inquiry. As one proceeds through a search, conducting the question negation session, establishing an overall strategy, selecting vocabulary elements, constructing specific search formulations, printing and evaluating samples of retrieved citations, and formulating and testing alternative hypothesis, one needs a rational basis on which to proceed. Unfortunately, current research can offer us little guidance in directions that ought to be taken in particular retrieval situations. There are few rules of conduct that can be offered that will guarantee success. Thus, online information retrieval should be regarded as interactive and heuristic rather than algorithmic

There are many strategies and heuristics that can be applied to increase the success of finding information (Bothma, et al., 2017; Savolainen, 2016; Harter, 1986). In our example it will be to identify research participants for an information behaviour study of cold case investigators. This include the choice of search terms (e.g., cold case investigators, cold case detectives) as well as related search terms that might also lead us to potential research participants; this will fit the solution of broadening the potential pool of participants (Badke, 2014). Examples would be to search for forensic scientists, homicide detectives, criminalists, pathologists. The use of building blocks, successive factions (Marchionini, 1995) and citation searching and citation pearl growing (Badke, 2014) have also been mentioned. According to Markey (2019) the citation pearl growing search strategy is a series of searches that a researcher implements to find relevant search terms and then incorporates them into follow-up searches. Citation pearl growing can be used to identify authors and the people they cited and their contacts if approached individually. We searched a South African database (Sabinet African Journals) for South African authors of articles on cold case investigation in order to identify institutions as well as people we might approach to participate or for referrals to cold case investigators. This led us to universities with departments related to cold case investigation such as a Department of Law and Criminology and Department of Forensic ScienceBates’ (1989) discussion of berrypicking as a new model of searching online and other information systems encouraged us to think outside the normal approaches. The berrypicking process includes two points namely, the continuing shift of information needs and queries due to learning from the information encountered; information needs are not satisfied from a single, final retrieved set of documents but by a series of selections and bits of information found along the way (Hearst, 2009). In this iterative process a variety of strategies can be used to expand the scope of search results. In addition Savolainen’s (2007, 2016) work on information landscapes and information horizons (although more relevant to traditional interpretations of information seeking) encouraged us to look at a wider variety of sources to identify opportunities for (i) access to institutional units (in the absence of a central cold case unit in South Africa), and (ii) recruiting individual research participants. We started with Internet searches, social media sites and known person (cf Figure 2). Information found can again trigger further insight on possibilities for searching. (This is in line with Bates’ 1989 berrypicking techniques.)

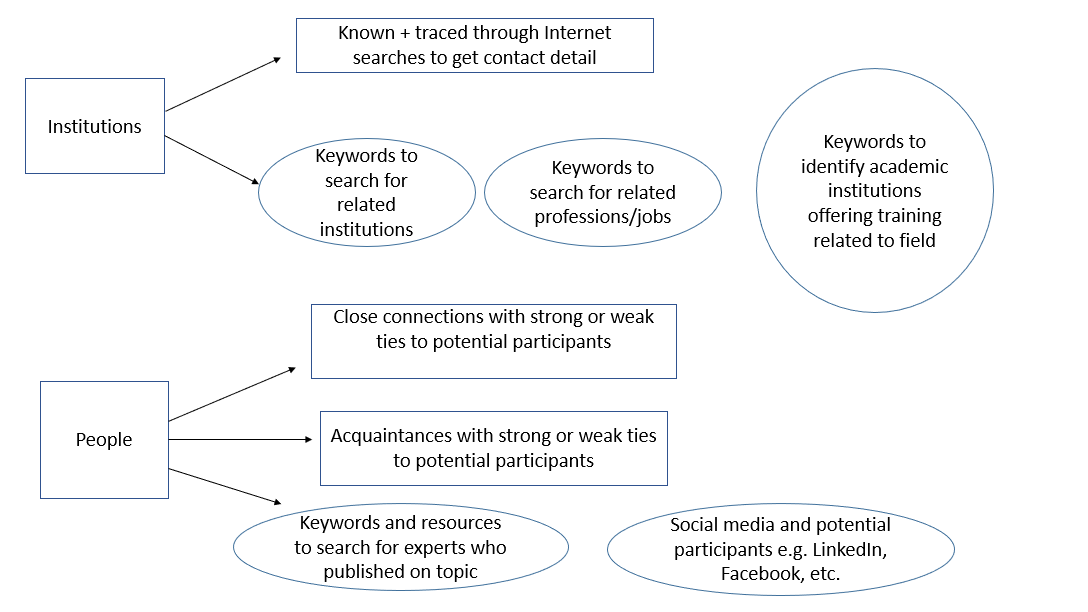

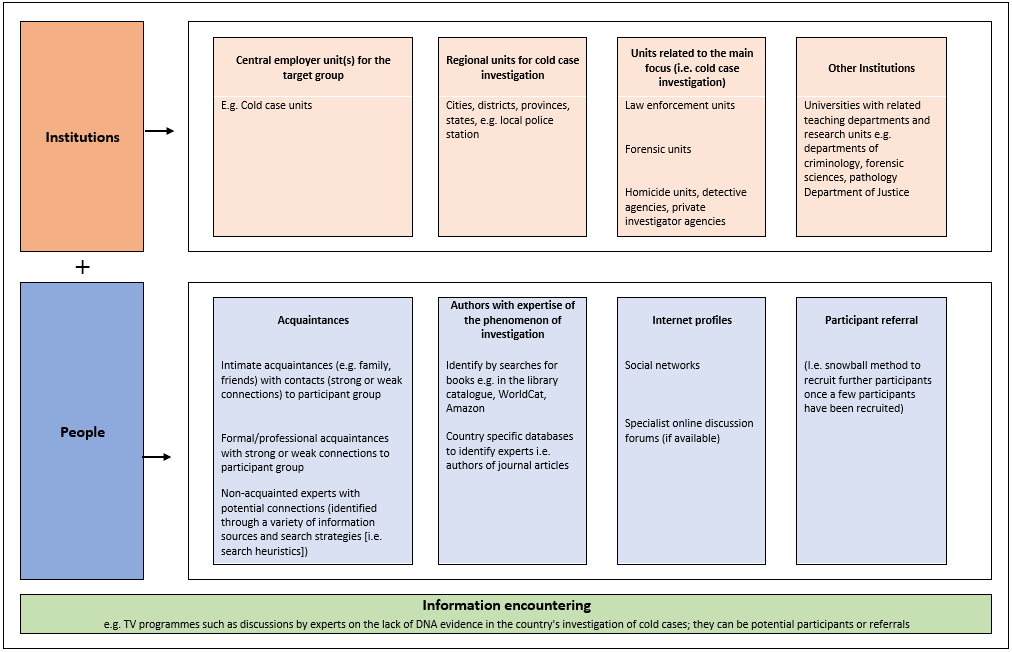

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the application of search heuristics that can be applied to research studies in various fields searching for (i) institutions and (ii) people to expand the pool of potential research participants. Figure 1 shows the heuristics and Figure 2 the detail for our exemplar: an information behaviour study of cold case investigators. For institutions there are known and obvious choices such as the South African Police Services as point of departure. In the absence of a dedicated cold case investigation unit, we need to do various Internet searches to identify other possibilities using synonyms and related terms (keywords) e.g. searching for cold case units in a regional unit district or city basis or homicide sections. The potential pool can also be expanded by using additional job labels (i.e., searching for related professions). We can search for related professions and jobs such as investigative forensic analysts, special investigating unit officers and homicide detectives. Academic departments are also a possibility; we however need to first identify relevant search terms. Police Science is a point of departure, but through trying various search strategies as also shown in Figure 2, we came up with other academic departments we might approach such as Department of Forensic Science, Department of Criminology and Department of Criminal and Procedural Law. For all of these we need to identify appropriate keywords as shown in Figure 1. Search heuristic can assist in finding people e.g. contacting acquaintances with connections (strong or weak ties) to potential participants. These include family and friends that have contact with the research participant group, professional acquaintances through work and contacting experts in the field though a variety of information sources and search strategies. Authors with expertise in the field can be identified by conducting searches on cold case investigations books and databases. Internet profiles of homicide detectives, active detectives, forensic scientists, criminalists and pathologists using social networks such as LinkedIn, Facebook and personal websites can be used. In Figure 2 we show how research participants can also be identified through information encountering which includes expert interviews conducted on television or cold case documentaries with contact information. (Research encountering is strongly associated with the work of Erdelez [2004]).

Figure 1: Application of search heuristics

Figure 2: Search heuristics to recruit research participants for a study in cold case investigation

Conclusion

As noted in the Introduction to our paper, information behaviour studies are no exception to challenges in research participant recruitment (Case, 2012; Fisher, et al., 2006). One of the most important barriers to recruiting and retaining research participants is that a researcher may not know where to look for research participants (Rubin and Babbie, 2008, p.102). Since we strongly belief that a research study of importance should not be abandoned due to challenges with participant recruitment, we used our interest in studying the information behaviour of cold case investigators in South Africa as an example. A scoping review of the literature identified many general challenges that are experienced by researchers. In addition 5 of the themes stood out for our example: lack of a dedicated unit or centralised body to give permission for a research study and to approve access to potential research participants and ways of recruitment, establishing contact with research participants, diverse labels for the job, too limited pool of potential research participants, and issues with community entrance. There are many general guidelines on research participant sampling and techniques or methods to consider. For purposes of our example five themes of solutions to challenges experienced with research participant recruitment stood out: recruitment strategies aligning with the contexts and characteristics of the research participants, non-intrusive methods for recruiting, extending research participant criteria to draw on a larger pool of potential research participants, snowball sampling and checking various social media. Although useful, these did not fully address our core challenges. We thus applied inductive reasoning to explore the value of search heuristics. The search heuristics shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2 can support participant recruitment for an information behaviour study of cold case investigators. It can also guide participant recruitment in other challenging contexts and for other disciplines. The scoping review guided our initial perceptions of solutions. Personal experience in online searching and further reading on search heuristics guided the suggestions we offer. The only challenge for which we still need to find a solution is the challenges that might be experienced with community entrance as sketched by Krauss (2014). This is an issue for a future paper.

About the author

Naailah Parbhoo-Ebrahim is a full-time lecturer in the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria. She holds a masters in Information Technology with specialisation in library services. She is currently completing her doctorate in Information Science at the University of Pretoria. Her research focus includes information behaviour, information retrieval, information ethics, cold case investigations and competitive intelligence. Postal address: University of Pretoria, Department of Information Science, Private bag X20, Hatfield, 0028, Pretoria, South Africa. She can be contacted at naailah.parbhoo@up.ac.za.

Dr Ina Fourie is a full professor and Head of the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria. She holds a doctorate in Information Science, and a post-graduate diploma in tertiary education. Her research focus includes information behaviour, information literacy, information services, current awareness services and distance education. Currently she mostly focuses on affect and emotion and palliative care including work on cancer, pain and autoethnography. Postal address: University of Pretoria, Department of Information Science, Private bag X20, Hatfield, 0028, Pretoria, South Africa. She can be contacted at, ina.fourie@up.ac.za.

References

- Akanbi, O.M. & Fourie, I. (2018). Information needs of pregnant women - once-off needs and needs for information monitoring revealed by the McKenzie two-dimensional model. Innovation, 2018(56), 163-190. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-104e141999.

- Aidley, D. (2019). Introducing quantitative methods: a practical guide. Red Globe Press.

- Alhojailan, M.I. (2012). Thematic analysis: a critical review of its process and evaluation. West East Journal of Social Sciences, 1(1), 39-47. https://fac.ksu.edu.sa/sites/default/files/ta_thematic_analysis_dr_mohammed_alhojailan.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190804013256/https://fac.ksu.edu.sa/sites/default/files/ta_thematic_analysis_dr_mohammed_alhojailan.pdf)

- Babbie, E.R. (2012). The practice of social research. Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- Badke, W. (2014). Research strategies: finding your way through the information fog (5th ed.). iUniverse.

- Bates, M.J. (1989). The design of browsing and berrypicking techniques for the online search interface. Online Review, 13(5), 407-424. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb024320

- Begun, A.L., Berger, L.K. & Otto-Salaj, L.L. (2018). Participant recruitment and retention in intervention and evaluation research. Oxford University Press.

- Bender, J.L., Cyr, A.B., Arbuckle, L. & Ferris, L.E. (2017). Ethics and privacy implications of using the internet and social media to recruit participants for health research: a privacy-by-design framework for online recruitment. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(4), e104. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7029

- Booth, A., Papaioannou, D. & Sutton, A. (2012). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. Sage Publications.

- Bothma, T., Cosijn, E., Fourie, I. & Penzhorn, C. (2017). Navigating information literacy: your information society survival toolkit (5th ed.). Pearson South Africa.

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P.M. Camic, D.L. Long, A.T. Panter, D. Rindskopf & K.J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, 2. Research designs:quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57-71). American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Burford, S. & Park, S. (2014). The impact of mobile tablet devices on human information behaviour. Journal of Documentation, 70(4), 622-639. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-09-2012-0123

- Carter, D.L. (2013). Homicide process mapping, best practices for increasing homicide clearance. Institute for Intergovernmental Research. https://www.iir.com/Documents/Homicide_Process_Mapping_September_email.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190930203049/https://www.iir.com/Documents/Homicide_Process_Mapping_September_email.pdf)

- Case, D.O. (2012). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs and behaviour (3rd. ed.). Emerald group Publishing Limited.

- Case, D. O. & Given, L. M. (2016) Looking for Information: A Survey of Research on Information Seeking, Needs, and Behavior. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Cooper, J., Lewis, R. & Urquhart, C. (2004). Using participant or non-participant observation to explain information behaviour. Information Research, 9(4), paper 184. http://InformationR.net/ir/9-4/paper184.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200715111357/http://informationr.net/ir/9-4/paper184.html)

- Couper, M.P., Singer, E., Conrad, F.G. & Groves, R.M. (2008). Risk of disclosure, perceptions of risk, and concerns about privacy and confidentiality as factors in survey participation. Journal of Official Statistics,24(2), 255-275. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096944/pdf/nihms269709.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200720103144/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096944/pdf/nihms269709.pdf)

- Creswell, J.W. (2014). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications.

- Cronin, J.M., Murphy, G.R., Spahr, L.L, Toliver, J.I. & Weger, R.E. (2007). Promoting effective homicide investigations. Police Executive Research Forum.

- Davis, R.C., Jensen, C. & Kitchens, K.E. (2011). Cold-case investigations: an analysis of current practices and factors associated with successful outcomes. RAND Corporation. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/237971.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20170704062527/https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/237971.pdf)

- Erdelez, S. (2004). Investigation of information encountering in the controlled research environment. Information Processing & Management, 40(6), 1013-1025. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2004.02.002

- Federman, D.D., Hanna, K.E. & Rodriguez, L. (2002). Responsible research: a systems approach to protecting research participants. The National Academies Press.

- Fisher, K.E., Erdelez, S. & McKechnie, L. (2006). Theories of information behavior. American Society for Information Science and Technology.

- Ford, N. (2015). Introduction to information behaviour. Facet Publishing.

- Gelinas, L., Pierce, R., Winkler, S., Cohen, I.G., Lynch, H.F. & Bierer, B.E. (2017). Using social media as a research recruitment tool: ethical issues and recommendations. American Journal of Bioethics, 17(3), 3-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2016.1276644

- Gemmill, R., Williams, A.C., Cooke, L. & Grant, M. (2012). Challenges and strategies for recruitment and retention of vulnerable research participants: promoting the benefits of participation. Applied Nursing Research, 25(2), 101-107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2010.02.003

- Given, L.M. (2008). The SAGE encyclopaedia of qualitative research methods (Vol. 1-2). Sage Publications.

- Given, L.M. (2015). 100 Questions (and answers) about qualitative research. Sage Publications.

- Govender, P. (2017). Investigating serial murder: case linkage methods employed by the South African police service. (Unpublished master dissertation). University of South Africa, RSA.

- Grant, M.J. & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91-108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Grove, S.K., Burns, N. & Gray, J. (2012). The practice of nursing research: appraisal, synthesis, and generation of evidence. Elsevier Saunders.

- Guclu, I. (2011). The information-seeking behavior of police officers in Turkish national police. ERIC. (University of North Texas Ph.D. dissertation).

- Hackett, P. (2016). Qualitative research methods in consumer psychology: ethnography and culture.

- Harter, S. (1986). Online information retrieval. Academic Press.

- Hearst, M.A. (2009). Search user interface. Cambridge University Press.

- Hennink, M., Hutter, I. & Bailey, A. (2011). Qualitative research methods. Sage Publications.

- Ingwersen, P. & Järvelin, K. (2005). The turn: integration of information seeking and retrieval in context. Springer.

- Jacobs, K.A., Wellman, A.R.P., Fuller, A.M., Anderson, C.P. and Jurado, S.M. (2016). Exploring the familial impact of cold case homicides. Journal of Family Studies, 22(3), 256-271. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2015.1065195

- Joubert, L. & Webber, M. (2020). The Routledge handbook of social work practice research. Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780429199486

- Ju, B. & Albertson, D. (2018). Exploring factors influencing acceptance and use of video digital libraries. Information Research, 23(2), paper 789. http://InformationR.net/ir/23-2/paper789.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6zzbhaO59).

- Koziol-McLain, J., McLean, C., Rohan, M., Sisk, R., Dobbs, T., Nada-Raja, S., Wilson, D. & Vandal, A.C. (2016). Participant recruitment and engagement in automated e-health trial registration: challenges and opportunities for recruiting women who experience violence. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(10), e281. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6515

- Krauss, K.E.M. (2014). A confessional account of the community entry phases of a critical ethnography: doing emancipatory ICT4D work in a deep rural community in South Africa. Proceedings of the 7th Annual SIG GlobDev Pre-ICIS Workshop ICT in Global Development (pp.1-31). http://aisel.aisnet.org/globdev2014/6 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200603221759/https://aisel.aisnet.org/globdev2014/6/)

- Kubicek, K. & Robles, M. (2016). Tips and tricks for successful research recruitment a toolkit for a community-based approach. Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute.

- Kumar, R. (2014). Research methodology: a step-by-step guide for beginners. Sage Publications.

- Labott, S.M., Johnson, T.P., Fendrich, M. & Feeny, N.C. (2013). Emotional risks to respondents in survey research: some empirical evidence. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 8(4), 53-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/jer.2013.8.4.53

- Leedy, P.D. & Ormrod, J.E. (2013). Practical research: planning and design (10th ed.). Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall.

- Marchionini, G. (1995). Information seeking in electronic environments. Cambridge University Press.

- Markey, K. (2019). Online searching: a guide to finding quality information efficiently and effectively (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Maungwa, T. & Fourie, I. (2018). Exploring and understanding the causes of competitive intelligence failures: an information behaviour lens In Proceedings of ISIC, The Information Behaviour Conference, Krakow, Poland, 9-11 October: Part 1. Information Research, 23(4), paper isic1813. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/23-4/isic2018/isic1813.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74FBb1rq7).

- Mertens, D.M. & McLaughlin, J.A. (2004). Research and evaluation methods in special education. Corwin Press.

- Meyers, E.M., Fisher, K.E. & Marcoux, E. (2007). Studying the everyday information behavior of tweens: notes from the field. Library & Information Science Research,29(3), 310-331. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2007.04.011

- Miller, F., Davis, K. & Partridge, H. (2019). Everyday life information experiences in Twitter: a grounded theory. Information Research, 24(2), paper 824. http://InformationR.net/ir/24-2/paper824.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/78moc4YgU).

- Morris, A. (2018). Selecting, finding and accessing research participants, in: a practical introduction to in-depth interviewing. Sage publications.

- Moscovitch, D.A., Shaughnessy, K., Waechter, S., Xu, M., Collaton, J., Nelson, A.L., Barber, K.C., Taylor, J., Chiang, B. & Purdon, C. (2015). A model for recruiting clinical research participants with anxiety disorders in the absence of service provision: visions, challenges, and norms within a Canadian context. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203(12), 943-957. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000400

- Namey, E.E., Guest, G., Thairu, L. & Johnson, L. (2008). Data reduction techniques for large qualitative data sets. In G. Guest & K. MacQueen (Eds.), Handbook for team-based qualitative research (pp. 137-162). AltaMira Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265348624_Data_reduction_techniques_for_large_qualitative_data_sets (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200812174336/https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265348624_Data_reduction_techniques_for_large_qualitative_data_sets)

- Neal, P. (2004). Using the internet to work: Police Officer information seeking behaviour. (Unpublished master’s dissertation). Royal Roads University, Victoria, BC.

- Newington, L. & Metcalfe, A. (2014). Factors influencing recruitment to research: qualitative study of the experiences and perceptions of research teams. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14(10), 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-10

- Pajo, B. (2018). Introduction to research methods: a hands-on approach. Sage publications.

- Parbhoo-Ebrahim, N. & Fourie, I. (2018). Which lens for a study of information retrieval systems for cold case investigations - activity theory, systems or ecological approach? In Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference, Krakow, Poland, 9-11 October: Part 1. Information Research, 23(4), paper isic1815. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/23-4/isic2018/isic1815.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74FBQkDyx).

- Patel, M.X., Doku, V. & Tennakoon, L. (2003). Challenges in recruitment of research participants. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 9(3), 229-238. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/apt.9.3.229

- Pérez-Cárceles, M.D., Pereñiguez , J.E., Osuna, E. & Luna, A. (2005). Balancing confidentiality and the information provided to families of patients in primary care. Journal of Medical Ethics, 31(9), 531-535. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jme.2004.010157

- Pickard, A.J. (2013). Research methods in information. Facet Publishing.

- Rapp, B. (2005). Homicide investigation a practical handbook. Loompanics Unlimited.

- Raymond, C., Profetto-McGrath, J., Myrick, F. & Strean, W.B. (2018). Process matters: successes and challenges of recruiting and retaining participants for nursing education research. Nurse Educator, 43(2), 92-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000000423

- Rook, M.M. (2018). Identifying the help givers in a community of learners: using peer reporting and social network analysis as strategies for participant selection. Tech Trends, 62(6), 71-76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11528-017-0200-6

- Roufa, T. (2017). Explore a career as a cold case investigator.https://www.thebalance.com/explore-a-career-as-a-cold-case-investigator-974509 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200812225908/https://www.thebalancecareers.com/explore-a-career-as-a-cold-case-investigator-974509)

- Rubin, A. & Babbie, E. (2008). Research methods for social work (6th ed.). Thomson Corporation.

- Ruthven, J. (2010). Training needs and preferences of adult public library clients in the use of online resources. The Australian Library Journal, 59(3), 108-117. DOI: 1080/00049670.2010.10735996.

- Savolainen, R. (2007). Information source horizons and source preferences of environmental activists: a social phenomenological approach. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(12), 1709-1719. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.20644

- Savolainen, R. (2016). Information seeking and searching strategies as plans and patterns of action: a conceptual analysis. Journal of Documentation, 72(6), 1154-1180. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JD-03-2016-0033

- Seidman, I. (2006). Interviewing as qualitative research: a guide for researchers in education and the social sciences (3rd ed.). Teachers college press.

- Sharon, T. (2018). 43 ways to find participants for research. https://medium.com/@tsharon/43-ways-to-find-participants-for-research-ba4ddcc2255b (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200812230042/https://medium.com/@tsharon/43-ways-to-find-participants-for-research-ba4ddcc2255b)

- Sicetsha, A. (2018). SAPS to launch cold case teams and crime detection academy. The South African. https://www.thesouthafrican.com/news/saps-launch-cold-case-teams-crime-detection-academy/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200812230222/https://www.thesouthafrican.com/news/saps-launch-cold-case-teams-crime-detection-academy/)

- Singh, Y.K. (2008). Research methodology. APH Publishing Corporation.

- Sitole, K.J. (2019). Submission of the annual report to the Minister of Police, Annual Report 2018/2019. http://pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/SAPS_Annual_Report_20182019.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200610022424/http://pmg-assets.s3-website-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/SAPS_Annual_Report_20182019.pdf)

- Smith, C.L. (2016). Privacy and trust attitudes in the intent to volunteer for data-tracking research. Information Research, 21(4), paper 726. http://InformationR.net/ir/21-4/paper726.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6m5H0ikHJ)

- Surmiak, A. (2018). Confidentiality in qualitative research involving vulnerable participants: researchers' perspectives. Forum: Qualitative social research,19(3), 12. http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.3.3099

- Symon, G. & Cassell, C. (2012). Qualitative organizational research: core methods and current challenge Sage Publications.

- Trochim, W.M., Donnelly, J.P. & Arora, K. (2014). Research methods: the essential knowledge base. Cengage learning.

- Walton, R.H. (2014). Practical cold case homicide investigations procedural manual. CRC Press.

- Watson, B., Robinson, D.H.Z., Harker, L. & Arriola, K.R.J. (2016). The inclusion of African-American study participants in web-based research studies: viewpoint. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(6), e168. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5486

- Watson, N.L., Mull, K.E., Heffner, J.L., McClure, J.B. & Bricker, J.B. (2018). Participant recruitment and retention in remote e-health intervention trials: methods and lessons learned from a large randomized controlled trial of two web-based smoking interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(8), 1-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/10351

- Wellstead, P. (2016). Information-seeking to support wellbeing: report of a study of New Zealand men using focus groups. New Zealand Library & Information Management Journal, 56(1), 21-27. https://www.academia.edu/31698265/Information-seeking_to_support_wellbeing_report_of_a_study_of_New_Zealand _men_using_focus_groups (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200812225357/https://www.academia.edu/31698265/Information_seeking_to_support_wellbeing_report_of_a_study_of_New_Zealand_men_using_focus_groups)

- Westbrook, L. (2014). Intimate partner violence online: expectations and agency in question and answer websites. Journal of The Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(3), 599-615. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.23195

- Yaksic, E. (2015). Addressing the challenges and limitations of utilizing data to study serial homicide. Crime Psychology Review, 1(1), 108-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23744006.2016.1168597

- Zutlevics, T.L. (2016). Could providing financial incentives to research participants be ultimately self-defeating? Research Ethics,12(3), 137-148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1747016115626756