Teen engagements with data in an after-school data literacy programme at the public library

Leanne Bowler, Manuela Aronofsky, Genevieve Milliken, and Amelia Acker.

Introduction. The study presents a preliminary model of teen engagement with data in the context of data literacy activities at the public library. The model contributes to knowledge in the area of human data interaction, specifically as relates to the affective domain, to data literacy, and to the special context of informal learning at the public library.

Method. The study takes a critical data literacy stance and is framed by theory about interest and engagement drawn from the field of informal learning.

Analysis. Data analysis was inductive and iterative, proceeding through multiple stages. Open coding of feedback forms and the observation notes from twenty-seven data literacy workshops for teens revealed facets of teen engagement with data in the public library.

Results. Feedback forms completed by teen participants suggest high interest and engagement with data during the data literacy activities. Themes derived from analysis help to tell the story of youth engagement with data literacy at the public library, including: personal connections to data, embodied learning, interactions with data through facilitation techniques (analogy as one such example), opportunities for inquiry and discovery, social arrangements that encourage interaction, and adopting a playful attitude to learning.

Conclusions. Future research in youth data literacy programmes at the public library should further explore the variables of engagement identified in this study.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2015

Introduction

The datafication of young peoples’ lives leads to profound questions about childhood, technology, and the equity of access to learning experiences with data. With teens’ lives intertwined so completely with data, adults have a role to play in facilitating teens’ interactions with data, not just as future data scientists but also, as data subjects whose own data contributes to the data economy. Today’s teens are not only people who will work with data in one way or another, but they are also data subjects whose own data contributes to the data economy. Data empowerment has important developmental implications. One of the most central is finding ways to provide young people with tools that will contribute to their growth, well-being, and ability to take charge of their lives. Achieving such autonomy relies on getting ‘adolescents’ fires lit’ (Larson, 2000, p. 170) so they take initiative with regard to their own lives. With this in mind we ask, how can libraries find ways to help teens develop the intrinsic motivation, attention, interest and effort needed to be more fully self-determining data producers and consumers? How indeed, when the focus of learning is something as complex as data literacy and the learning occurs in an informal, voluntary, drop-in setting like the public library? Engagement is the key.

This paper considers the public library as a vital space for the development of key life skills and dispositions around data. We report here on Exploring Data Worlds at the Public Library, a three-year empirical research study that took place at a public library in the United States and which looked at the state of library programmes to support data literacy. Specifically, the study examined how libraries are helping teens, as data subjects, gain an understanding of the processes involved in data creation, collection, and aggregation with networked devices, platforms, and information services. The study uncovered a void in both mental models around data and actual data skills (Acker and Bowler, 2017, 2018; Bowler, et al, 2019; Bowler et al, 2017) and links between cognitive, affective, and behavioural aspects of teen perspectives on data (Chi et al, 2018). The study also produced a series of 11 unique data literacy workshops which were used to open a window on teen engagement with data.

In this paper we continue our analysis, attempting to build a preliminary model of teen engagement with data in the context of the public library and, to put it simply, discover what teens enjoy. We begin with a review of recent literature on data literacy skills, data literacy programming in libraries, and theories of informal learning and engagement in out-of-school environments (the library being one such example). We then introduce the methods and design for our study on teen engagement with data and conclude with a discussion of our findings and suggestions for further research.

Background

In this section we provide background on the emerging research about data literacy, with a focus on data activities in libraries. We also take a look at the nature of informal learning at the public library and explore research on engagement in after-school activities.

Data literacy

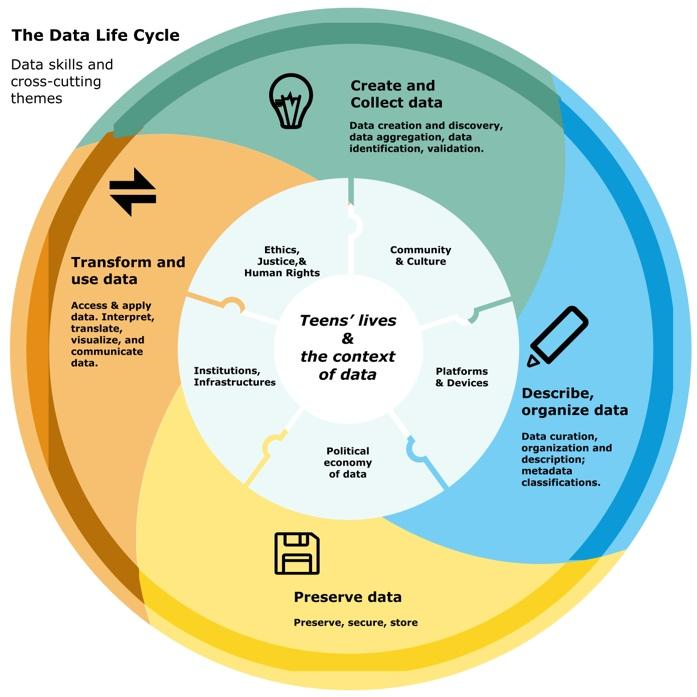

Data literacy is often defined as the ‘ability to read, work with, analyse and argue with data as part of a larger inquiry process’ (D’Ignazio and Bhargava, 2016). In the field of Information Science, the definition of data literacy includes skills necessary for the curation and preservation of data (Lyon and Brenner, 2015). Traditional approaches to data literacy have emphasised quantitative reasoning by focusing on numeracy, statistics, and computer programming but data literacy is, more accurately, a complex array of skills, knowledge, and humanistic reasoning to be applied throughout the data life cycle (See Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: The data life cycle in the everyday lives of teens

Still relatively new to the field of library and information science, the concept of data literacy is under-theorised and lacking a single definition. This is not surprising, as even in academic literature there is an agreement that the nature of data itself can be hard to define (Borgman, 2015). Hunter-Thomson (2019) argues that definitional problems associated with data consequently make data literacy difficult to teach: ‘...sometimes the variety of data we use can make it challenging for us to talk to one another about integrating data into our teaching because we are using the same word, data, but referring to different things.’ (p. 84).

We note that Ford, in his book, Introduction to Information Behaviour (2015, p. 13), states that ‘one person’s data can be another’s information, and vice versa’, suggesting that in the field of information behaviour data can be viewed through an information lens.

Conceptual models of data literacy are often mapped to the data life cycle in library and information science scholarship. Carlson and Johnston (2015), for example, correlate data-related information competencies in higher education (including non-quantitative competencies such as documentation, visualisation, and cultures of practice) to the notion of a data lifecycle that flows from data creation to preservation. Prado and Marzal (2013, p. 130-131), also researching higher education data literacy methods in library and information science, also take a process approach, adapting traditional information literacy models to data. Bowler and her co-authors, investigate data literacy activities in the public library, and argue for a similar life cycle model, albeit situated in the everyday life contexts of young people (Bowler, et al, 2017, p. 30).

Broader understandings of data literacy as a humanistic endeavour are also emerging. In order to succeed, everyone - encompassing K-12 and university students, scientists, business people, and beyond - must have the ability to find, read, extract, analyse, understand, and in some cases visualise data in order to succeed in our digital world.

Data literacy in libraries

While there is a consensus on the importance of data literacy within the world of library services for youth, there is little empirical research that supports best practices of informal learning about data. One reason for this may be that data literacy is a concept new to the field of library and information science: a theoretically-framed pedagogy is only just emerging (whether in formal or informal learning environments). Despite a dearth of empirical, theoretically-grounded research on data literacy at the public library, libraries are marching ahead with the education of the public about data (as indicated by the 2019 Fortune article ‘We’re in a data literacy crisis. Could librarians be the superheroes we need?’).

The American Library Association identifies Education and Lifelong Learning as one of the core values of modern librarianship (ALA, 2019). This includes providing the public with the means to learn data literacy skills so they can successfully access, evaluate, manage, preserve, and use data in meaningful ways. For teens, these opportunities present themselves through informal, after-school learning activities at the library. Usually these activities are free and operate on a drop-in basis.

Data literacy at the public library often finds itself situated under the banner of privacy protection (We note here that privacy awareness is but one facet of data literacy). For example, the American Library Association promotes Privacy Week, an annual campaign to educate the public about their privacy rights. Privacy Week at the New York Public Library offers programming such as ‘Understanding how to secure your iPhone/iPad’, and ‘Social media & your privacy’ (New York Public Library, 2019). Brooklyn Public Library also provides cybersecurity mini-sessions on topics like Mobile security, Get to know your terms of service, Phishing, Passwords, and Threat modelling (Brooklyn Public Library, 2019).

Notably, the programmes mentioned above are marketed and focused on adult audiences, despite being perfectly positioned for teens, or even tweens, many of whom already have their own digital devices and social media platforms. One example of data literacy activities designed specifically for youth in the after-school setting of the public library comes from the Exploring Data Worlds at the Public Library research study, which analysed a series of data literacy activities designed for tweens and teens at a public library (Acker and Bowler, 2017, 2018; Bowler, et al, 2019; Bowler et al, 2017). Their research argues for ‘a holistic and humanistic approach to data in public library programming for youth that is aligned with broad, cross-cutting themes such as data infrastructures, data rights, and data subjectivity’ (Bowler, et al, 2019, p. 1).

This project fits under the broader remit of critical data literacy - the body of technical, social, cognitive, and communication competencies and practices needed by citizens in order to navigate the cyber-infrastructure of the 21st century. Public libraries, as spaces where learning is embedded in the everyday lives of people, is one such environment where an holistic approach to data and learning can naturally emerge.

Critical data literacy

In their thematic analysis of the critical data literacy discourse, Špiranec et al (2019) highlight the contextual and interpretive nature of data, it’s ideological foundations and ethical dimensions. From a pedagogical stance, data literacy ‘is grounded in authentic experiences and the educands own reality’. Tygel and Kirsch (2015) draw a parallel between critical data literacy and the critical pedagogy of Brazilian educator Freire (1996), for whom literacy was not just for reading words but to read the world. Education for critical data literacy can be an emancipatory process that builds a capacity to read, manipulate, communicate, and produce data in ways that expose its non-neutrality and its roots in social hierarchies, transactions, and processes. A critical data practice is embedded within broader inquiry, prompted by critique and a hope for transparency and empowerment (Gutiérrez, 2018).

The step of empowerment is particularly important for teens. As producers and consumers of massive amounts of data, it is vital that they have robust models and strategies for manoeuvring the highly networked society in which they live. Being introduced to a set of skills is one thing, putting them into action is another. This raises an important question: how might young people enact a critical data literacy if given the opportunity? This question becomes even more complex when the skills and approaches in question are taught in the voluntary, drop-in setting of informal, after-school sites of learning - such as the public library. This environment, and the complications that come with it, has guided this study. Interest and curiosity, in particular, may be key factors in engaging youth with data.

Teen engagement in after-school learning

This study into teens and data literacy at the public library is informed by a growing body of theory and best practices in informal learning environments, including research about interest and engagement. Research has demonstrated that informal learning in after-school programmes has a positive impact on youth and is therefore worthy of consideration in and of itself, rather than as a simple replication of the formal learning structures established in the K-12 environment. A meta-analysis of 73 afterschool programmes found that the personal and social development of youth were enhanced through their participation in structured, voluntary, out-of-school activities (Durlak and Weissberg, 2007). Research in after-school programmes has also shown that they are a rich environment for learning, providing the motivational environment and social arrangements that help propel interest and engagement in a topic, hobby, or new skill (Larson, 2000; Csikszentmihalyi and Kleiber, 1991; Csikszentmihalyi and Larson, 1984). Larson, an early advocate for after-school, community-based programmes for youth, argues that adults interested in positive youth development should ‘give youth activities equivalent status to school, family, and peers as a focal context of development’ (Larson, 2000, p. 178).

Research and practice in the pedagogy of informal learning (outside the school setting) has paid particular attention to engagement, a concern for librarians working in public libraries, where participation is voluntary and interest-driven. What exactly do we mean by engagement? Engagement is more than simple participation: engagement relates to a broader set of experiences such as the challenge of the activity, the associated sense of belonging, and the depth of absorption into the flow of the activity. For the purposes of this study, we draw on Walker et al’s definition of engagement as ‘the extent to which young people are focused on and excited about the activities they are participating in at a particular point in time and space’ (Walker, et al, 2005, p. 403). Activities that are personally meaningful help to trigger interest (Hidi and Renniger, 2006) which, if sustained over time, can put someone into a state of flow - a deep concentration in a challenging but not impossible task (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

Although often used synonymously with terms like interest and motivation, engagement is a distinct quality related to learning, according to Renninger and Bachrach (2015). In their work exploring ways to foster interest and engagement in an out-of-school learning environment (a biology workshop) they note that the two constructs are not synonymous. Interest is a cognitive and affective state. Engagement, while it begins with cognitive and affective aspects, must also include behavioural features related to participation and the enactment of interest (for example, focusing on an activity, showing surprise, remembering an insight, making something). Engagement is interest operationalised.

Bartko (2005) has also described engagement as the interplay between affect, behaviour, and cognition – calling this the ‘ABCs of engagement’. He urges programme staff in after-school environments to be ‘attuned to the affective, behavioural, and cognitive demands of the activity within the context of the developmental needs of and resources available’ (p. 115). Some of these factors include opportunities for stimulating experiences and activities that foster relationships. Bartko emphasises that the first encounter with a programme is critical to engagement. Young people quickly assess their ease with peers, the qualities of the staff, and whether the activity fits their interests and competencies.

In settings where young people attend programmes on a voluntary basis, interest and engagement are critical and, as noted above, very quickly determined. Luckily, the strength of after-school programmes seems to be in their ability to engage youth. Larson (2000) found that the most engaging environments for youth are in structured, voluntary, after-school programmes. It was only in the context of structured, voluntary after-school activities that the teens in this study reported both high intrinsic motivation and high concentration. Further, the highest order of motivation and attention was reported during activities related to the arts and hobbies and within the context of community organisations.

Not surprisingly, the higher the availability of choice, the higher the level of concentration and focus, the suggestion being that goodness of fit is central to engagement. Choice is correlated to engagement, reflecting a relationship to young people’s personal interests (Shernoff and Vandell, 2008). Shernoff and Vandell recommend further research into types of engagement in relation to specific afterschool activities and more exploration into the relationship between cognitive and affective aspects of engagement. In this paper, we delve deeper into such questions of engagement specifically as they relate to encounters with data at the public library.

Methods and study design

This paper reports on research from the Exploring Data Worlds at the Public Library research study, extending our previous work exploring youth data literacy in the context of Teen Services at the public library, with the goal of supporting positive and meaningful youth engagements with data. In our earlier work we explored youth conceptions of data (Acker and Bowler, 2018; Bowler et al, 2017; Chi et al, 2018) and the perspectives of library staff in terms of data literacy activities (Bowler, et al, 2019). In this paper we continue to look at teens, this time focusing on the specific features associated with engagement with data, asking the question, what do teens find engaging and fun (or, boring and not worthy of their attention) in their interactions with data at the library?

Data sources

Findings in this paper are drawn from our formal examination of two data sources from the Exploring Data Worlds research project: (1) the observation notes from 27 data literacy workshops on 11 unique data topics, held at the public library with 95 teens, and, (2) feedback forms completed by teen participants following each workshop.

Data literacy workshops: Approximately 95 teens participated in 27 after-school, drop-in workshops on a variety of topics related to data (Table 1 below outlines the workshop titles and topics). All participants were teens between the ages of 14 to 17 years. Of the 95 participants, 52 identified as female and 37 as male, with six leaving the open-ended question about gender blank (‘I identify my gender as…’). The workshops were held in a teen services area at an urban, mid-sized city in the North-Eastern United States, and each was designed and facilitated by members of the Exploring Data Worlds research team, with library staff in attendance.

The workshops tackled varying levels of learning, from basic awareness of data to specific data management skills. Although any of these workshops could stand alone, they were designed to be part of a holistic, life-cycle approach to data flows. Indeed, we have argued that librarians should design individual data literacy activities as part of a larger conceptualisation of data systems. (See Bowler et al, 2019). Samples of the workshops as well as the protocols for observation have been archived at Harvard’s Dataverse, under the project title, Exploring Data Worlds at the Public Library (Acker & Bowler, 2019a, 2019b).

Figure 2: Data Keychains activity

| Title and description of Data Literacy Workshops for Teens, 2017-2018 |

|

1. Cell Phone Surgery – Dissecting old cellphones to investigate how they create, transmit, and store data. 2. Data Bending – Glitching photos to explore concepts of data permanence, preservation, and malleability. 3. Data Keychains – Visualising data subjectivity through keychains created from personal information. 4. Data Postcards – Creating data visualisations of teens’ daily data. 5. Data Rights – Teens thinking critically about personal data rights, the ideals and the realities. 6. Data Scavenger Hunt – Examining and locating entry points of data—hotspots, routers, cameras, etc.—within the library. 7. Data Silhouettes – Representing teens’ daily interactions with data in a way that reflects transaction and impact. 8. Dog Data – Using open, community data to locate dogs in the neighbourhood. 9. Internet Cats– Tracking cats, people, and identities through metadata. 10. Mapping Data Flows – Following the flow of data as it moves through time and space. 11. Secret Data – Understanding encryption through secret codes and password protection techniques. |

Feedback forms: Although 27 after-school workshops were run during the life of the project, feedback forms were completed for only 23. We also have feedback from participants in Data Day but have not included that data in our analysis since it includes adult participants. In total, 95 feedback forms were completed by teen participants. We note that many of the participants attended more than one workshop but we did not record multiple attendees, treating each feedback form as a unique entity.

Figure 3: Teens gave a thumbs up or thumbs down on the data literacy workshops

Data analysis

Data analysis was inductive – arising from the data - and iterative, proceeding through multiple stages. The first step was an open coding of the observation notes from the 27 data literacy workshops by two researchers, each person working independently to identify facets of engagement. Whenever the text suggested engagement (or a noteworthy absence), the researchers used codes to describe that moment. A total of 26 unique codes were generated and applied to the texts 325 times. A third researcher joined the analysis team and together, the three researchers implemented a code sort exercise, synthesising the 26 codes into six broad categories, understood at the time to be provisional. These were: making personal connections, cognitive breakthroughs, interactivity and embodied learning, gamification or the value of play, investigation through inquiry, and, analogy. The provisional categories were also applied to an analysis of the feedback forms. Following this stage of analysis, synthesis notes were prepared which explained the broad categories and linked them to evidence through quotes from the workshop observation notes. Analysis continued, still building upon the six provisional categories. A further review of the synthesis notes and the workshop observation notes, codes, coding memos by the principal investigators resulted in a re-labelling of categories (for clarity), the addition of new categories related to affect, time and space, meaning making, materials, facilitation techniques. A final list of ten themes helps to tell the story of youth engagement with data literacy activities at the public library. Table 2 below outlines the themes.

| Themes that tell the story of engagement in data literacy activities |

|---|

|

1. Personal connections to the data (data about oneself, one’s community) 2. Insights about data (discovery and a ha!! moments, a cognitive breakthrough) 3. Interest (curiosity, disinterest, distraction, reluctance, openness to discovery. Note that interest is a cognitive state but it can be accompanied by the affective state of curiosity) 4. Embodied learning (hands-on, contact with materials, multi-sensory, learning through doing, making and unmaking) 5. Attitude of playfulness (puzzles, treasure hunts, challenges, arts and crafts, general gamification of learning) 6. Meaning making (sense-making techniques, use of analogy, question prompts, talk and conversation, comprehension) 7. Affect (emotional aspects, both good and bad – excitement, boredom, frustration, surprise, disgust (creepy), curiosity) 8. Time and space (time of day, amount of time spent on activity: effect of the learning space – open design, maker spaces, class room structures) 9. Materials (platforms, devices, tools, craft materials) 10. Techniques for facilitating interactions with data (investigation through inquiry, question prompts, use of analogy, storytelling, games, mentoring and peer-to-peer learning, making and unmaking) |

Results and discussion

Based on evidence from the feedback forms, responses to the workshops from teens were overwhelmingly positive, with 95.87% giving the data workshops a thumbs up. Two percent gave the workshops a thumbs down and two percent left this question blank. The average score for 23 workshops, on a scale of one to five where five is best, was 4.44. In addition, 88.8%, of the teens surveyed reported being happy or most happy with their experiences.

The most popular workshop, with a score of 4.8/5.0, was Cell Phone Surgery, where teens dissected old cell phones to locate data entry and exit points in order to make the connection between data and devices concrete. Participants said the best thing about this workshop was ripping phones apart and breaking the phone. The worst thing for participants in Cell Phone Surgery was that it ended. It seems that the unmaking of cell phones allowed for an embodied, material connection to data (tempered perhaps with a small dose of rebellion) which helped to make this an engaging experience learning about the properties of data.

Although not a poor score, the least favourite workshop, according to feedback from teens, was the Scavenger Hunt, where teens and facilitators sought out sensors and data entry points in the library (rated 4.09/5.00 by the teens). Participants in this workshop were asked to move around the library, seeking sensors (CCTV, WIFI, the catalogue, etc.). They then returned to the teen section and created a map of sensors, with yarn connecting sensor points on the map. While looking for things and finding each object in the library was a positive feature for the teens, some didn’t like running around, getting up, and counting. Mixed reviews for this activity are perhaps based on the teens’ intentions with regard to their time at the library. If they had planned to hang out around a table with friends after-school, an activity that asked them to uproot themselves and leave the teen section may not have had an appeal. On the other hand, some of the teens did appreciate the puzzle aspect of the scavenger hunt and the map-making craft activity that followed.

Engagement characteristics in data literacy activities

In this section we discuss emerging themes related to teens and engagement with data at the public library, weaving them into a descriptive narrative of our observations. This study was not designed to test interventions nor do we make claims regarding cause and effect. Rather, the themes are intended to paint a rich picture of teen engagement with data in an after-school setting, showing us what engagement does (or doesn’t) look like and pointing to variables that might be associated with it.

In this study, we used observations from Renninger and Bachrach (2015) about interest as a cognitive and affective state as a starting point for understanding interactions with data. Not surprisingly, because it is integral to engagement, interest weaves its way throughout all the themes identified in this study. Renniger and Bachrach (2015, p. 64) identify several triggers for interest, which in turn trigger engagement. They are: autonomy, challenge, group work, hands-on activity, instructional conversation, novelty, and personal relevance. Feedback from the participants as well as our reading of the observational notes seems to indicate that these triggers, to varying degrees, were at play in the data literacy activities we presented to teens and captured in our coding.

Across all workshops, engagement was notably higher when the teen participants were able to make a personal connection to data during the activity, finding themselves or their community in the data. We note that this aligns with Dawes, and Larsen (2011, p. 265) who suggest that personal connection is a central mechanism for engagement in after-school learning situations because it provides an entry point to learning. After-school learning is voluntary and, at least from the perspective of teens, incidental to the reasons why they go to the library. They must find the hook immediately in order to be engaged. A concrete example comes from the workshop entitled Dog Data, where participants visualised dog license city data. Observational notes indicate that teens seemed uninterested in using random dog license data but were excited to locate dogs in their own neighbourhood or even their own dog.

In addition, a personal connection to the subject matter not only increased participation levels but also raised the quality and depth of discussions that took place between the participants and facilitators. For example, the popular Data Keychains activity asked participants to visualise their personal data and identities with coloured beads in order to make a keychain that seemingly encodes themselves (i.e. coloured beads could represent a teen’s age, gender, likes and dislikes). Not only were teens able to see how their own lives could be encrypted and represented, but by making a personal connection to the data they were able to see the significance in how someone might be able to learn about them. As one of the facilitators noted:

Once our keychains were completed, we enjoyed comparing those which used the same key/legend, noticing which elements were the same and where they differed. What does data say about us, and how is our data similar/different? (Susan, workshop facilitator – name anonymised)

Establishing a connection to and interest with the subject is important for helping teens become receptive to exploring complex data concepts in an after-school setting. Young people may have just come from a full day at school: they want fun and friendship, not a lecture. In this study, intentional use of techniques for facilitating interactions with data helped to bring focus and attention to the activities presented. The Cell Phone Surgery workshop offers one model. In this activity, teens quite literally broke a mobile phone. The unmaking of the phone piqued everyone’s curiosity but this activity was in fact a serious inquiry. Interestingly, Pearce, et al (2010), writing about engagement in after-school learning, suggest that the hook for interest should be centred on moral, civic, and social goals that transcend self. Thinking about this through the lens of Cell Phone Surgery, we note that the breaking was accompanied by conversation facilitated by library staff, posing deeper questions about data (i.e. Where does the data from your cell phone live? Do you own it? Who shares the data captured by your mobile phone?).

Embodied learning (e.g., tactile learning experiences that engage the senses and the body) also worked well as a mechanism for engagement. Throughout the workshops it was noted that wherever there was some sort of physical interaction in the activity, engagement with data was more visible. Adding a physical component to a data activity helps to build a bridge between abstract concepts of data and the materiality of how data is manifested. By dissecting phones and coming into contact with individual components, teens were able to grasp the physical nature of phones instead of the vague nature of cloud storage and the elusiveness brought on by sleek design. Workshop facilitators indicated that the physicality of deconstructing phones seemed to lead to greater engagement:

No part (of the workshop) seems boring and they are engaged all the time. I think if we have more phones, they will keep dissecting for an even longer time. (Emily, Workshop Facilitator - name anonymised)

Shernoff and Vandell (2008) argue that the social arrangements around informal learning are also key to youth engagement. This means opportunities for collaboration, sharing, and sustained interaction with peers and facilitators should be built into the activity. In the Data Silhouettes activity, where participants made an electric circuit with conductive tape that circled around a small drawing of their online lives, teens responded positively to the physicality of the craft activity. The teens in this activity showed interest and curiosity in the outcome. The act of crafting something together around a table helped scaffold conversation about data. Comments from the facilitator noted that,

The crew ended up working together and helping each other out to solve issues resolving the circuits. We also talked out loud about our data silhouette plans… (Karen, workshop facilitator - name anonymised)

Meaning-making with data can be difficult because digital data, the metadata used to represent it, and the systems governing their creation and use, are abstract concepts. If teens can’t be engaged with the basic concept of data, then how can they ask critical questions about its role in their lives? How can teens manage something they can’t see or imagine? Methods are needed to help make data understandable to teens. We highlight here the use of analogy as one such meaning-making tactic. For example, in the Mapping Data Flows activity, comparisons were made to the journey of a letter from mailbox to house. Teens imagined the pathway of an envelope along the path of data flows (We note here that one librarian suggested many teens have no idea how ground mail works). The Data Silhouettes activity asked teens to accept their circuit board as a proxy for daily connections to personal devices and digital platforms. In the Data Keychain activity, teens designed indexes to the coloured beads, making analogous connections to the concept of encryption and metadata. The use of analogies created a space for teen engagement in ways that were fun and accessible and provided entry points for more complex and multivariate modes of thinking about parallel relationships such as networked infrastructures or the invisible flow of data.

A discovery (the a ha! moment) in a workshop, while not always grand nor even guaranteed, could foster engagement with data literacy. We saw many surprising moments where teens made a small discovery about data that could meaningfully change their interactions with it. For example, in the Secret Data workshop teens tested the security of their password and learned how easy it could be cracked. Exclamations by teens and their excitement as they gathered around the laptops to test their passwords were noted by the facilitators:

When it wasn’t their turn at the laptop, they watched the screen eagerly to see the cracking time increase or decrease and peeked over each other’s shoulders to see what methods they were trying, learning from one another’s mistakes (Liang, Workshop Facilitator – name anonymised)

Workshops that were framed by an attitude of inquiry allowed for possibilities for engagement with data to emerge. Rather than tell teens about data, data activities should allow for exploration driven by questions, surprises, and discovery. For an after-school audience of teens, these discoveries must be easy to achieve. A small discovery is better than no discovery. Planning for the possibility of success, no matter how slight, is a good tactic for building engagement with data.

A general attitude of playfulness wove its way throughout the workshops. Teens responded positively to data activities where a sense of play, gaming, or crafting were involved. Two workshops with strong game elements – Secret Data and Data Scavenger Hunt – also coded positively for enjoyment and enthusiasm in the affective theme. Interestingly, these two workshops also saw high levels of collaboration and interaction between peers and facilitators. In the Data Scavenger Hunt, where teens walked around the library to discover sensors and internet-enabled devices,

The teens seemed to enjoy finding the different devices. It felt like an adventure, leaving the teen space. They were excited in their conversation before we embarked on our hunt, talking about interesting it would be to find the security cameras (Emily, Workshop Facilitator – name anonymised)

Conclusion

Larson (2000), in his exploration of the psychology of positive youth development in after-school learning, identified engagement as the secret ingredient. What might engagement look like in the context of data literacy activities at the public library? Our study revealed that engagement in learning about data includes the following features: personal connections to data, embodied learning, interactions with data through facilitation techniques (analogy as one such example), opportunities for inquiry and discovery, social arrangements that encourage interaction, and adopting a playful attitude to learning. We acknowledge that our study does not measure learning outcomes nor was it intended to do so. Rather, we have used engagement as a construct for building a practical model to help shape the design of an exciting programme of public education about data. Of note here are the contributions that this study makes to the pedagogy of informal learning at the public library.

Future research in data literacy at the public library should further explore the variables of engagement identified in this study. For consideration might be the nature of engagement when teens take a more direct hand in the development of data literacy activities at the public library. The workshops we studied were designed by the Exploring Data Worlds research team, a group of adults with expertise in data, information, and youth library services. A natural next step in this project would be to ask young people to design data literacy activities in ways that they think would engage teens, informed by the preliminary framework presented in this paper. Our hope is that librarians, alongside teens, apply the findings from this study to the design of learning experiences that support the development of critical data literacy.

Acknowledgements

We thank the young people and library staff who participated in these studies. Their contributions are invaluable. This project was made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), RE-31-16-0079-16.

About the author

Leanne Bowler is Associate Professor at School of Information, Pratt Institute, New York, United States. She received her PhD from McGill University, Montréal, Canada. Her research interests are in youth technology practices and how libraries support young peoples' data and information competencies in socio-technical environments. She can be contacted at, lbowler at pratt.edu

Manuela Aronofsky is the Middle School Technology Integrator at The Berkeley Carroll School in Brooklyn, New York. Her interests include educating youth in data and digital literacy and teaching the act of reading as an empathy and community-building experience. She can be contacted at, maronofsky at berkleycarroll.org

Genevieve Milliken is a LIS Research Scientist at New York University and a graduate of Pratt Institute’s School of Information. Her current research interests include research data management, web archiving, academic use of version control systems, and software preservation. She can be contacted at, genevieve.milliken at nyu.edu

Amelia Acker is an Assistant Professor at the School of Information at the University of Texas at Austin. She researches data literacy, social media data, and information infrastructures that support digital cultural memory. She can be contacted at, aacker at ischool.utexas.edu

References

- Acker, A. & Bowler, L. (2017). What is your data silhouette? Raising teen awareness of their data traces in social media. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Social Media & Society (pp. 1-5). ACM Digital Library. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/3097286.3097312

- Acker, A. & Bowler, L. (2018). Youth data literacy: teen perspectives on data created with social media, and mobile device ownership. In Proceedings of the 51stHawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 1923-1932). ScholarSpace. http://dx.doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2018.243

- Acker, A. & Bowler, L. (2019a). Data activity workshops for exploring data worlds. Harvard Dataverse, 2. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ATEVBQ

- Acker, A. & Bowler, L. (2019b). Research instruments for exploring data worlds. Harvard Dataverse, 2. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OUXMPU

- American Library Association. (2019). Core Values of Librarianship. http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/corevalues (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200518045750/http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/corevalues)

- Bartko, W.T. (2005). The ABCs of engagement in out-of-school time programs. New Directions for Youth Development, 2005(105), 109-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/yd.110

- Bhola, H.S. (2017). Literacy. In J.D. McDonald & M. Levine-Clark (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences (4th ed., vol. 1-7, pp. 3479-3491). CRC Press.

- Borgman, C.L. (2015). Big data, little data, no data: scholarship in the networked world. The MIT Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9963.001.0001

- Bowler, L., Acker, A. & Chi, Y. (2019). Perspectives on youth data literacy at the public library: teen services staff speak out. The Journal of Research on Libraries and Young Adults, 10(2), 1-21. http://www.yalsa.ala.org/jrlya/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Bowler-Acker-Chi_PerspectivesOnYouthDataLiteracy_FINAL.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20191103130015/http://www.yalsa.ala.org/jrlya/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Bowler-Acker-Chi_PerspectivesOnYouthDataLiteracy_FINAL.pdf)

- Bowler, L., Chi, Y., Acker, A. & Jeng, W. (2017). "It lives all around us": aspects of data literacy in teen’s lives. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 54(1), 27-35. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2017.14505401004

- Brooklyn Public Library. (2019). CyPurr session: library privacy week extravaganza!https://www.bklynlibrary.org/calendar/cypurr-session-library-central-library-info-20181020 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190617061601/https://www.bklynlibrary.org/calendar/cypurr-session-library-central-library-info-20181020)

- Carlson, J. & Johnston, L. (2015). Data information literacy: librarians, data and the education of a new generation of researchers. Purdue University Press.

- Chi, Y., Jeng, W., Acker, A. & Bowler, L. (2018). Affective, behavioral, and cognitive aspects of teen perspectives on personal data in social media: a model of youth data literacy. In G. Chowdhury, J. McLeod, V. Gillet & P. Willett (Eds.), Proceedings of the 13thInternational Conference on Information: transforming digital worlds (pp. 442-452). Springer. (Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 10766). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78105-1_49

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. Harper Perennial.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. & Kleiber, D.A. (1991). Leisure and self-actualization. In B.L. Driver, P.J. Brown & G.L. Peterson (Eds.), Benefits of Leisure (pp. 91-102). Venture Publications.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. & Larson, R. (1984). Being adolescent: conflict and growing in the teenage years. Basic Books.

- Data Quality Campaign. (2018). Administrator data literacy fosters student success. Data Quality Campaign. https://dataqualitycampaign.org/resource/administrator-data-literacy-fosters-student-success/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190810142721/https://dataqualitycampaign.org/resource/administrator-data-literacy-fosters-student-success/)

- Dawes, N.P. & Larson, R. (2011). How youth get engaged: grounded-theory research on motivational development in organized youth programs. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 259-269. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0020729

- D'Ignazio, C. & Bhargava, R. (2016). DataBasic: design principles, tools and activities for data literacy learners. The Journal of Community Informatics, 12(3). http://ci-journal.net/index.php/ciej/article/view/1294 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200725061624/http://ci-journal.net/index.php/ciej/article/view/1294)

- Durlak, J.A. & Weissberg, R.P. (2007). The impact of after-school programs that promote personal and social skills. Collaborative for academic, social, and emotional learning (NJ1). ERIC. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED505368.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200711110646/https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED505368.pdf)

- Ford, N. (2015). Introduction to information behaviour. Facet Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.29085/9781783301843

- Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed (revised). Continuum.

- Gutiérrez, M. (2018). Data activism and social change. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Hidi, S. & Renniger, K.A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111-127. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

- Hunter-Thomson, K. (2019). Data literacy 101: what do we really mean by “data”? Science Scope, 43(2), 84-88. http://dx.doi.org/10.2505/4/ss19_043_02_84

- Larson, R.W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist, 55(1), 170-183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.170

- Lyon, L. & Brenner, A. (2015). Bridging the data talent gap: positioning the iSchool as an agent for change. International Journal of Digital Curation, 10(1), 111-122. http://dx.doi.org/10.2218/ijdc.v10i1.349

- Moran, G. (2019, August 31). We’re in a data literacy crisis. Could librarians be the superheroes we need? Fortune. https://www.f3nws.com/news/we-re-in-a-data-literacy-crisis-could-librarians-be-the-superheroes-we-need-ee10b614c2a (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200813082234/https://www.f3nws.com/news/we-re-in-a-data-literacy-crisis-could-librarians-be-the-superheroes-we-need-ee10b614c2a)

- New York Public Library. (2019). Privacy week: October 15th-22nd. https://www.nypl.org/privacyweek (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200716101146/https://www.nypl.org/privacyweek)

- Prado, J. & Marzal, M.Á. (2013). Incorporating data literacy into information literacy programs: core competencies and contents. Libri, 63(2), 123-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/libri-2013-0010

- Qlik. (2018). Lead with data: how to drive data literacy in the enterprise. Qlik. https://www.qlik.com/us/-/media/files/resource-library/global-us/register/analyst-reports/ar-how-to-drive-data-literacy-within-the-enterprise-en.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200813055607/https://www.qlik.com/us/-/media/files/resource-library/global-us/register/analyst-reports/ar-how-to-drive-data-literacy-within-the-enterprise-en.pdf)

- Renninger, K.A. & Backrach, J. (2015). Studying triggers for interest and engagement using observational methods. Educational Psychologist, 50(1), 58-69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2014.999920

- Shernoff, D.J. & Vandell, D.L. (2008). Youth engagement and quality of experience in afterschool programs. In J. Gallagher (Ed.), Afterschool Matters Occasional Paper Series (No. 9, Fall 2008, pp. 1-14). The Robert Bowne Foundation. https://repository.wellesley.edu/object/wellesley8962 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/https://web.archive.org/web/20200813072326/https://repository.wellesley.edu/object/wellesley8962)

- Špiranec, S., Kos, D. & George, M. (2019). Searching for critical dimensions in data literacy. In Proceedings of CoLIS, the Tenth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science. Information Research, 24(4), colis1922. http://InformationR.net/ir/24-4/colis/colis1922.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200529034623/http://informationr.net/ir/24-4/colis/colis1922.html)

- Tygel, A. & Kirsch, R. (2015). Contributions of Paulo Freire for a critical data literacy. In Proceedings of Web Science 2015 Workshop on Data Literacy (pp. 318-334). https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alan_Tygel/publication/278524333_Contributions_of_Paulo_Freire_for_a_critical_data_literacy/links/5581469d08aea3d7096e6a31/Contributions-of-Paulo-Freire-for-a-critical-data-literacy.pdf?origin=publication_detail (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200813073447/https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alan_Tygel/publication/278524333_Contributions_of_Paulo_Freire_for_a_critical_data_literacy/links/5581469d08aea3d7096e6a31/Contributions-of-Paulo-Freire-for-a-critical-data-literacy.pdf?origin=publication_detail)

- Walker, J., Marczak, M., Blyth, D. & Borden, L. (2005). Designing youth development programs: toward a theory of developmental intentionality. In J.L. Mahoney, R.W. Larson & J.S. Eccles (Eds.), Organized activities as contexts of development (pp. 399-418). Lawrence Erlbaum.