published quarterly by the university of borås, sweden

vol. 24 no. 4, December, 2019

Introduction. This exploratory study contributes to the research on information evaluation as well as emotions’ role in the process. The project was inspired by the cognitive authority theory by Patrick Wilson. Its goal was twofold, to explore: 1) if media may fulfil the role of cognitive authority, and 2) if (and to what extend) emotional reactions to specific citations depend on the presented source of information.

Method. We conducted exploratory research using biometric methods (face-tracking and eye-tracking), completed by a questionnaire survey, to examine the influence of a source on the information assessment process. The research sample consisted of 100 respondents of similar sociocultural background: students of journalism.

Analysis. Intensity of emotional reactions (mimic expressions) to presented texts was recorded and measured with the FaceReader. Statistical data were collected and calculated, concerning reactions for 6 emotions (joy, anger, disgust, surprise, sadness, fear), as well as information evaluation expressed in a survey.

Results. The results confirm importance of institutional source in contents’ assessment, as we observed changes in emotional attitudes towards information at the moment its source is known. The questionnaire also confirmed relations between emotional attitude and evaluation of information credibility.

Conclusion. The study confirmed the role of medium as a cognitive authority. We observed common (for the research sample) trends in perceiving selected sources as more credible than others. The results showed also a higher level of negative emotions for information from a source evaluated as less credible. The results showed also that (as for statistically significant differences in the research sample) a higher level of negative emotions was observed for information from a source evaluated as less credible.

The problem of evaluation of information is one of the core areas in information science, with long tradition of research. Different concepts have been applied in such studies, including information relevance, reliability, credibility or cognitive authority The influence of information source on people's thinking and decision-making found interest in information science, as it will be briefly presented in the literature review below. The project presented in this paper joins this research stream, offering the results of the exploratory study realised with biometric methods. Its goal was twofold: to explore 1) if media may fulfil the role of cognitive authority, and 2) if (and to what extend) emotional reactions to specific citations depend on the presented source of information.

The concept traditionally debated in information science in regard of information evaluation is relevance, called even the key notion in the emergence of information science and the basic notion in most of its theories (Saracevic, 1975, p. 323). Indeed, from the early 70ies it has been widely studied from different perspectives, mainly in the context of information seeking and retrieval (Mizzaro, 1997; Saracevic, 1996). However, with the growth of research incorporating sociocultural perspective, this concept has become insufficient as ‘relevance studies in IR have, by and large, been concerned with users’ relevance judgments and have in that sense been connected to a more or less individualistic view on the matter’ (Andersen, 2004, p. 11). The researchers have started to adopt the concepts which are closely related but emphasise different aspects of the complex process of information assessment (Danielson & Rieh, 2007; Flanagin & Metzger, 2008; Rieh & Hilligoss, 2008; Rieh, Kim, Yang, & St. Jean, 2010; Savolainen, 2007). Depending on the research approach they examined such notions (and relation between them) as credibility, information quality, believability of media, and reliability or trustworthiness.

The extensive study of credibility with respect to the use of information technology was undertook by Danielson and Rieh (2007). They pointed out that usage of the term credibility in information research started from the 1990ies and gained prominence along with the growth of the Internet. As Danielson (2005) indicated, among the problems with the selection of Internet resources are relative lack of filtering and gatekeeping mechanisms, preponderance of source ambiguity, and relative lack of source attributions. In the world where 'media become our window on the world and their power consists in creating frames of our perception' (Gackowski, 2014, p. 109), social media have become the important news sources (Newman, Fletcher, Kalogeropoulos, Levy, & Nielsen, 2018) and the phenomenon of fake news is serious social problem (Cooke, 2018; Froehlich, 2017), the knowledge of the mechanism of second hand knowledge acquisition is essential.

The concept which received many attention in information research in the context of Internet resources’ selection is cognitive authority, originally introduced by P. Wilson (1983) as ‘influence on one’s thoughts that one would recognize as proper’ (p. 15). It provides a framework for understanding how individuals deal with acquiring knowledge from 'second hand' sources, being beyond own personal live experience – ‘what others told me’ (P. Wilson, 1983, p. 13). As personal experience is limited, the question is which of hearsays treat as a proper one. It is the reason why individuals develop cognitive strategies to recognize or establish the information sources authority. As P. Wilson (1983) put it, ‘The person whom I recognize as having cognitive authority is one whom I think should be allowed to have influence on my thinking’ (p. 15). Cognitive authority depends on the area of interest and its level may vary in different spheres. What is important, cognitive authority not necessarily have to be related to individuals, it may be also attributed to a group of people, institutions, organizations (i.e. publishers, journals etc.) or books (P. Wilson, 1983, pp. 166-167). According to Wilson there are several factors which influence individual decision about source authoritativeness, like good reputation, recommendations, expertise knowledge or success in particular sphere of interest, persuasiveness, or personal trust.

The usefulness of the concept became especially apparent in the context Internet seeking. Fritch and Cromwell (2001) created the Model for Ascribing Cognitive Authority as a theoretical framework for studying Internet information seeking, as they assumed that authorship and affiliation may be the most important criteria influencing process of evaluation. Studies of Rieh and Belkin (1998; 2000) and Rieh (2002) contributed significantly to the research in this area. They found out that information quality assessment based on source credibility, with considerable attention to institutional authority, academic and governmental institutions at first place (Rieh & Belkin, 1998, p. 288). They observed that although topical interests was an important facet of judgment, more significant were the facets related to information quality and cognitive authority judgments (Rieh & Belkin, 2000, p. 35). Rieh (2002) also characterized cognitive authority as having six facets: trustworthiness, reliability, scholarliness, credibility, officialness and authoritativeness; of these, trustworthiness was perceived as the primary facet (p. 153).

Being a framework to understand the individual information assessment, this concept include sociocultural factors and may be studied from constructivist or constructionist perspective. McKenzie (2003) noted that cognitive authority might be understand different if considered from a constructivist perspective: ‘cognitive authority decisions are seen to be the result of underlying cognitive processes, that is, based on the information seeker's interpretation of source characteristics in light of a body of beliefs and attitudes that the information seeker has developed from an initial childhood stock’ (p. 262) or constructionist: ‘calls for a deeper analysis of the language used to create descriptions of authority and considers descriptions of cognitive authority not as accurate representations of pre-existing beliefs or attitudes but, rather, as examples of everyday fact construction: discourse created to fulfil a particular function within a particular setting’ (p. 262-263). This distinction is at the same time an invitation to consider different roots of cognitive authority creation, different understanding of the notion in consequence, and to apply different research methods to explore the phenomena.

The concept of cognitive authority was adopted in exploration of different groups’ information assessment (i.e. Doty, 2015; Farrow & Moe, 2019; Hirvonen, Tirroniemi, Terttu, & Kortelainen, 2018; Hughes, Wareham, & Joshi, 2010; Mansour & Francke, 2017; Neal & McKenzie, 2011; Oliphant, 2009; Savolainen, 2007). In this article we would like to focus on the research pertaining the students’ information assessment process. We were interested in wide perspective of factors influencing students’ assessment due to the fact that the relation between credibility and cognitive authority is not well-defined, and the credibility itself has not been clearly defined so far (Rieh & Hilligoss, 2008). We assume that the notions of credibility and cognitive authority are in this context similar to the notion of relevance: as Froehlich (1994) summarised, even though clear definition has not been establish, the scientists understand better the criteria which influence users’ judgments.

First of all, the review of the literature shows the diversity of the studies in the area, although it is not unexpected having in mind sophistication of credibility judgments process. The course of this process was the object of interest in the study by Hilligoss and Rieh (2008) conducted among American students. Their findings reveal that credibility assessment depends on social context in which information is sought and should not be perceived only as an attribute of information or a source. The whole process of information evaluation is complex and takes place on 3 levels: besides the level of interaction, which is usually object of research, it incorporates also the level of developing the construct of credibility and level of individual heuristics used to assess credibility. Hilligoss and Rieh did not indicate any particular factor or source determining the credibity assesment, but observed that students relied on multiple types of media and resources within one information seeking episode. There are the studies, however, where authors tried to identify the sources’ features influencing the evaluation process. Metzger, Flanagin, Eyal, Lemus, and McCann (2003) analysed students' perceptions of information sources’ credibility, such as newspaper, television, magazine, radio and the Internet - the latter was perceived as least credible, but the differences were slight. They also noticed that even if a Web content was perceived as less credible, students used mostly those sources for education assessment. In the similar vein were the findings of study of upper secondary school students: they attributed higher credibility to print sources even if they preferred to use digital ones (Francke, Sundin, & Limberg, 2011; Sundin & Francke, 2009). While seeking information pupils paid attention to authorities associated with the document, with special respect to collective authority (i.e. organization) perceived as stronger than that of an individual, although author’s expertise was also seen as important. Collective authority also turned out to be important in the study by Neal, Campbell, Williams, Liu, and Nussbaumer (2011) who examined students' behaviour while seeking health information. Although the influence of cognitive authority was one of the objects of their interest, their findings in this topic are limited to observations that "cognitive authority seems to increase with the retrieval of traditionally trustworthy sources such as neutral medical and governmental organizations" (p. 31), and the peers are not seen as authoritative sources. In turn Lim (2013) focused on influence of such factors as students’ knowledge and peripheral cue of Wikipedia articles (measured as number of references) on credibility perception. Her findings demonstrated stronger effect of a superficial factor (i.e. peripheral cue) than a substantial one (knowledge).

The studies presented in above section prove how complex is the process of information assessment, how many factors may influence its course on different levels, and what are the consequences. They also present how difficult is to find research methods adequate for accurate catching the picture of this process. As Rieh and Hilligoss (2008) highlighted, many people experienced the difficulties trying to describe their internal, cognitive process of credibility assessments. Researchers exploring the phenomenon of cognitive authority based on content analysis (Doty, 2015; Huvila, 2013; Neal & McKenzie, 2011; Savolainen, 2011), in-depth interviews (McKenzie, 2003; Rieh & Belkin, 1998; Savolainen, 2007), surveys (Hirvonen et al., 2018; Neal et al., 2011) or tried to use multiple data collection methods combining verbal protocols during searches, search logs, diaries and interviews (Hughes et al., 2010; Rieh, 2002; Rieh & Belkin, 2000). We think that the complex nature of the cognitive authority concept poses the same challenges as credibility, and therefore the call for research methods that can accommodate those issues (Rieh & Hilligoss, 2008) is still valid.

It is the reason why we decided to conduct exploratory research using biometric methods (face-tracking and eye-tracking), completed by a survey, to examine the influence of a source on the information assessment process. Until now the emotions were studied as factors which accompanied or motivated information seeking (Kuhlthau, 1991; Nahl, 2004; Savolainen, 2014, 2015; T. D. Wilson, 1999). We would like to explore them as the results of interaction with information itself. As our study is exploratory in nature, we decided to focus on the part of assessment process called by Hilligoss and Rieh (2008) an interaction level, although we are aware that a judgment process depends on person’s activity on the construct or heuristic level as well. We also decided to apply constructivist approach to determine what similarities (if any) in the reactions may be determined in the group of people with similar sociocultural background (i.e. students being the research sample). Unlike in previous research using this approach, we decided not to base on 'discourse as a window to the minds of the informants' (Tuominen, Talja, & Savolainen, 2002, p. 276), but enrich this view by knowledge about respondents’ emotions recorded and calculated with biometrics methods to examine those issues.

The empirical study addresses three major research questions:

The experiment was realized in one week of April 2017, in cooperation with the Laboratory of Media Studies, University of Warsaw. We decided to divide our respondents into two groups. We showed them the same short information, however they were presented as coming from different sources. The research material consisted of citations from diversified sources (individual or institutional), but in this article we present only the results concerning information from institutional ones. The respondents read three short information, presented as coming from:

Citations were presented to the respondents in random order at the computer monitor – signed with one of the media, depending on the group. They were not informed that the source name could be 'incorrect'. Graphic design (logo, colours) were also prepared to suggest that information did come from a signed medium.

The research sample consisted of 100 respondents of similar sociocultural background: living in a big city, aged 20-25 (both men and women), students of a large university (the University of Warsaw), with a similar knowledge on contemporary media: students of journalism and media studies. We also assumed their political affinity, as according to the State Opinion Poll, the voters aged 18-24 supported the Civic Platform, a liberal-conservative political party run by Donald Tusk, in last 4 parliamentary elections in Poland (2005-2015), rather than the Law and Justice, national-conservative party run by Jarosław Kaczyński (Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej, 2017).

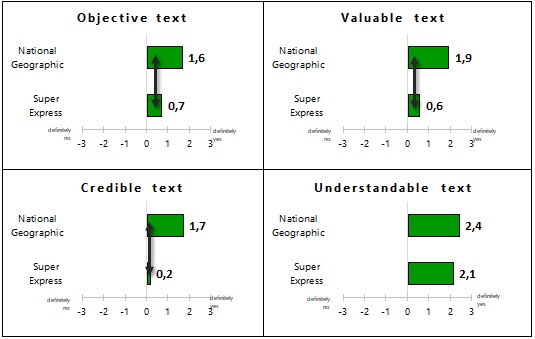

The respondents were measured individually and anonymously, and informed that the experiment was recorded. When read an information, each of them was asked to evaluate the features of the citations (in a form of a few statements) on the Likert scale. Rieh (2002) characterized cognitive authority as having six facets: trustworthiness, reliability, scholarliness, credibility, 'officialness' and authoritativeness. Due to the specificity of the Polish language and the research object, we selected the following features to be evaluated by the respondents: text credibility, value, objectivity, and understandability.

Two biometric measurements were realised, i.e. eye-tracking and face-tracking, monitoring and registering gaze paths and fixations (for the former), and facial movements (for the latter) revealing emotions of the respondents while reading texts. Eytracking results are not presented in this article, as their role was supportive: to indicate potential parts of sentences evoking the most intensive emotional reactions.

Intensity of emotional reactions (mimic expressions) to presented texts were recorded and measured with the FaceReader application offered by Noldus. Biometric data were calculated with an algorithm developed and owned by the Neuroidea Company. Respondents’ faces were recorded with a high quality camera, and then the application analysed each frame of the recording. A 500-points grid is placed on an image of face, and the application measures tension of 44 face muscles, calculating changes in distances between selected grid points, resulting from muscle tension. Data are related to the Facial Action Coding System (developed by Ekman and Friesen (1978), and systematised for 6 basic emotions: anger, joy, sadness, fear, disgust, and surprise). Finally, FaceReader offers information of the type and intensity of emotions experienced in contact with a stimulus (a text in this case). These data are then transformed to the values between -100 and 100. where positive values mean increase, and negative – decrease of an emotion in contact with a stimulus, related to a neutral level.

Eye-tracking measurements were carried out to verify which specific parts of texts or screenshots evoked particular emotions. Visual attention of the respondents was measured with the stationary SMI eyetracker, 60 Hz.

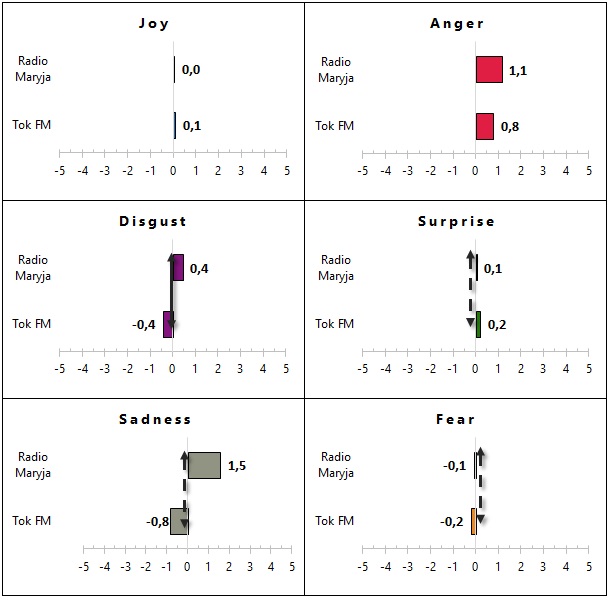

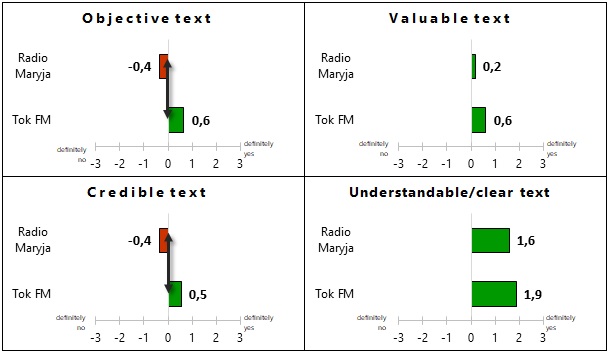

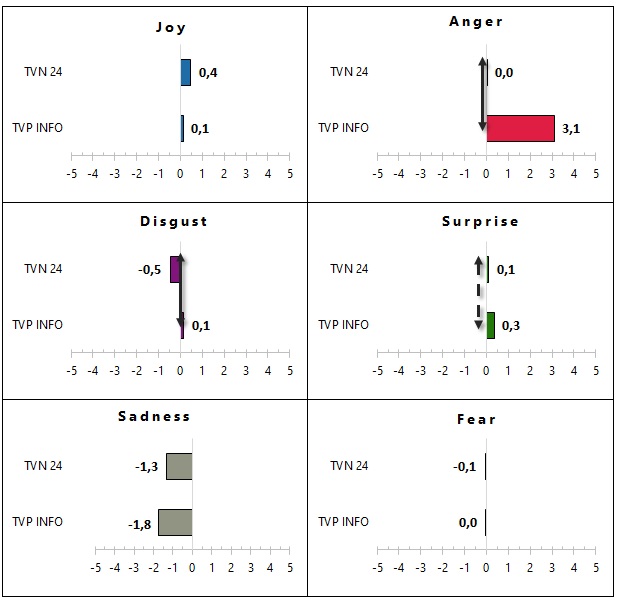

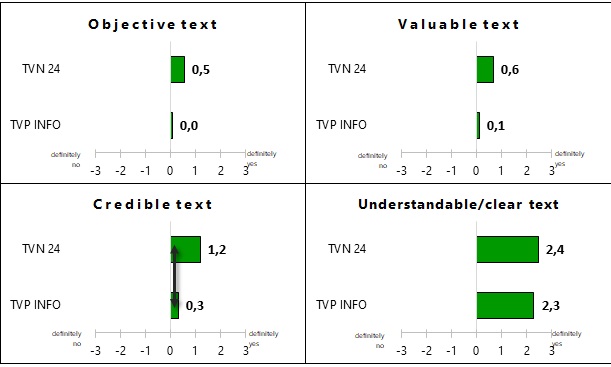

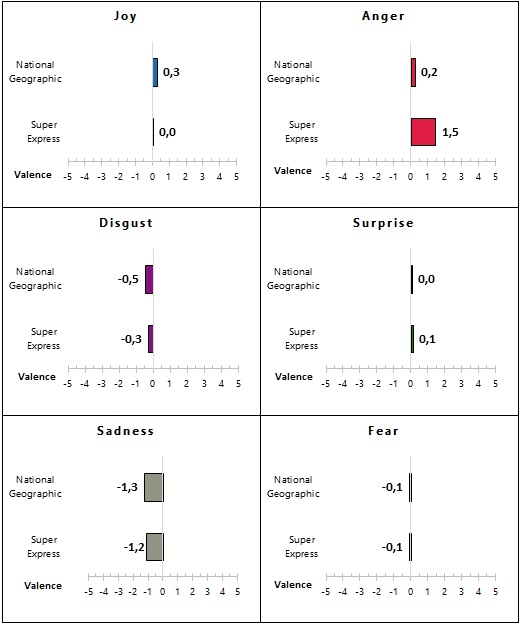

Statistical data were collected and calculated, concerning reactions for 6 emotions (joy, anger, disgust, surprise, sadness, fear), as well as those concerning reactions to the statements presented to the students. The results below are presented in charts, detailed statistical data are available in the appendix.

The findings will be presented in the following order: radio citations, TV citations, and journal citations finally. Sections for each citation include statistical data and charts for 6 emotions (joy, anger, disgust, surprise, sadness and fear), followed by data concerning answers to the questionnaire filled by the respondents while reading the citations.

Citation No 1: The Vatican: John Paul II did not know about pedophilia. This citation was presented in two versions: published at the website of either Tok FM, the news and current affairs radio of a center-leftist bias, or Radio Maryja, the conservative, ultra-catholic broadcasting.

Higher intensity of negative emotions was observed for Radio Maryja. Statistically significant results were found for disgust (p=0.02), and statistical trends for sadness (p=0.077) and fear (p=0.60). It is important that emotions with the highest medium value were also highly dispersed, as for anger (p=0.554, SDR.Maryja=3,11, SDR.TokFM=2,89) and sadness (p=0.77, SDR.Maryja=6,98, SDR.TokFM=5,84). This reveals disparities of these emotions while information evaluation. Emotional disposition of the respondents corresponds with their cognitive evaluation of information – results for evaluation of the text’s credibility (p=0.008) and objectivity (p=0.004) are statistically significant. They indicate that the information presented by Tok FM is well thought in these categories.

Citation No 2: Crowds at demonstrations in Warsaw. Protests also in other cities. This citation was presented in two versions: published at the website of either TVN24, the private news channel, owned by the Discovery Communications, or TVP INFO, the public TV news channel, in subjection to the current national-conservative government.

Case No 2 also presents differences in emotions depending on a source of information, and increased intensity of negative emotions (disgust, anger, sadness) in reaction to the communicate signed by TVP INFO. The most intensive is anger (p=0.037, SDTVN24=6,33, SDTVP=7,88), with high diversity of respondents’ reactions, followed by disgust (p=0.009, SDTVN24=1,01, SDTVP=1,21), both results statistically significant. An explanation is required, that before the study a lot of protests against toughening up the law on abortion took place all over Poland, engaging many young people. Media obedient to the governing party (TVP INFO included) presented very critical relations from these demonstrations (Sztyber, 2017). One may presume that a high level of anger among the respondents can result from this situation. Results from the questionnaire also present more positive evaluation of TVN24 in all aspects of evaluation, although only one (credibility, p=0.022) is statistically significant.

Citation No 4: Fist mass extinction of wild animals since 65 million years? – citation accompanied by a short news. Published at the website of either National Geographic nature magazine or Super Express, the Polish daily tabloid.

Results of this observation are very interesting. Despite differences in emotions depending on a source, no result is statistically significant. However, as for the results of cognitive evaluation of this citation, three categories are statistically significant, namely objectivity (p=0.002), value (p=0.000), and credibility (p=0.000). The respondents value higher information offered by National Geographic.

First of all, our study – like these mentioned in the literature review – confirm significance of a source’s influence on information evaluation, i.e. the phenomenon of cognitive authority. Our observations also confirm, that – as discussed by P. Wilson, ‘cognitive authority not necessarily have to be related to individuals, it may also be attributed to a group of people, institutions, organizations (i.e. publishers, journals etc)’ (1983, pp. 166-167). Moreover, the following research projects showed that people preferred so-called collective authority than that of an individual (Neal et al., 2011; Sundin & Francke, 2009). Froehlich (2019) indicated that media could fulfil the role of cognitive authority, hoping to make them tools for fight against the problem of fake news. Our study confirms these observations, indicating a significant influence of a source/ medium (i.e. radio station, TV channel, journal title) on evaluation of information on both affective reactions and cognitive process of evaluation of information quality.

The fact that similarities in evaluations in these two aspects were observed for the research sample enables conclusion of validity of the constructivist perspective we accepted (McKenzie, 2003). In this perspective we assumed that in case of a relatively homogenous group, of similar sociocultural background, we would be able to observe statistically similar emotional reactions and evaluations (resulting from previously shaped beliefs) of identical information cited from different sources. It also confirms the importance of the level of developing construct of credibility (described by Hilligoss and Rieh, 2008) for the whole process of information evaluation. The research procedure we applied minimised the level of heuristic and interaction, and even so the respondents’ evaluations differed significantly depend on an information source.

Evaluation of information credibility in all three cases differed depending on a source and was statistically significant, therefore we can prove influence of cognitive authority on evaluation of credibility. Situation is different for other categories the respondents were asked for (objectivity, value and understandability). We did not find any relation between a source and evaluation of information understandability. Statistically significant was the result for evaluation of value only in case No 3.: Super Express, a tabloid – vs National Geographic, a popular science journal. Information from the latter was perceived as more objective. The assumption that evaluation in these two categories could result from a popular science character of the title, or other features, like respondents’ knowledge or their information needs, require further, in-depth studies.

Our study shows also, that more intensive negative emotions (anger or disgust) were observed for information from sources evaluated as less credible, the results were statistically significant for radio and TV communicates. However, high standard deviation of the results for emotional reactions (i.e TVP INFO/TVN24, anger p=0.037, M TVN24=0.01, SDTVN24=6,33, M TVP=3,08, SDTVP=7,88) in relation to the standard deviation for the survey results show that emotional reactions depends much more on an individual’s character than a process of cognitive evaluation

Two of our cases (No. 1 and 2) were so emotionally engaging that the results were statistically significant or statistical trend could be found. No statistically significant result was found in case No 3. Interestingly, the latter information received the most unambiguous evaluation as credible, valuable, and objective. It means that lack of emotional engagement in information does not pre-empt the result of its cognitive evaluation. However, in statistically significant results (or revealing statistical trends) reception of information from a source perceived as less credible was related with a higher level of negative emotions.

These results can also by analysed in the perspective of comparing credibility of different type of media. As for the survey results, our observations comply with the results of Savolainen (2007), who noticed that in general, newspaper were perceived as somewhat more credible information sources than television and radio – in our study information from National Geographic, was assess as the most credible (M=1,66), after TVN 24 (M=1,18), and Tok FM (M=0.53) However, due to the research procedure, where information was bereft of its context, in which the users usually receive TV or press news, conclusions in this area, based on the survey only, would not we justified.

We would like to strongly emphasis an exploratory character of this study. Verification if the combination of research methods (biometric methods and questionnaire survey) would enable response to research questions required limitation of influence of other variables on observed behaviour. Therefore, the study did not refer to a wide context of these behaviour, like information searching or more complex heuristics enabling verification of information credibility. Another important limitation of this study is that even if we can conclude about emotions experienced by the respondents thanks to qualitative methods applied, we cannot determine the reasons of these emotions. We believe also that, as two citations which evoked strong emotions had clear political nature, in further studies we should directly check political affinity of our respondents and add it as a variable to explain potential differences in their reactions.

The study confirmed the role of medium as a cognitive authority. We also observed common (for the research sample) trends in perceiving selected sources as more credible than others. It was clearly visible for a cognitive evaluation process (a questionnaire survey). The study of emotions revealed higher differentiation of the respondents’ reactions. The results showed also that (as for statistically significant differences in the research sample) a higher level of negative emotions was observed for an information from a source evaluated as less credible. However, information can also be perceived as clearly credible/incredible, even if emotions related to its perception are so different that statistically insignificant. Generalisation of this observation on larger group requires further studies. So far emotions were studied as an element of information searching process, being evoked by this process. In this study we presented emotional reactions in the very moment of reception of information, evoked by a message and its source. This is quite new and promising area of information behaviour research.

It is worth noting that these results are only a part of a project, aiming at analysis of different aspects of influence of a source on information perception, including variations in reception if a citation is signed with a recognizable name (like Shakespeare) or a modern pop singer (Wasilewski, Kostrzewa, Kowalski, & Pawłowska, 2017).

The study omitted the stage described in previous projects as essential for credibility evaluation, i.e. information searching. However, it should be noticed that in a modern world we receive information without searching it on a daily basis. This phenomenon obviously has been intensified by dissemination of social media. Information presented there do not actually differ from those being evaluated by our respondents – short forms including a content, a source, and (potentially) graphics. Regarding the problem of fake news, being disseminated mostly in these channels, research in this area become more and more important.

The authors deeply acknowledge technological support from the Neuroidea Company, devices and applications of which were applied in this project.

Anna Mierzecka works at the Faculty of Journalism, Information and Book Studies, University of Warsaw, Poland, and as research team member at Media Analysis Centre. Anna does research in Library and Information Science, she focuses on the research of information behaviour, scientific communications, academic libraries, information literacy and the issues of digital divide. She has received a PHD research grant from Polish National Science Center for a study of digital information sources use in science. She can be contacted at anna.mierzecka@uw.edu.pl.

Jacek Wasilewski works at the Faculty of Journalism, Information and Book Studies, University of Warsaw, Poland. His research interests are narratives, semiotics, culture studies, advertisements, emotions Methods: narrative analyses, semiotic analyses, measurment of emotions, content analyses. Since 2011 he has been the head of the documentary studies specialty aimed at the development of multimedia narrative forms in journalism. He can be contacted at jacek.wasilewski@uw.edu.pl.

Małgorzata Kisilowska works at the Faculty of Journalism, Information and Book Studies, University of Warsaw, Poland. Her research interests are: information culture, information literacy, information behaviour, reading patterns.

| Emotion | Mean 1 | Standard deviation 1 | Mean 2 | Standard deviation 2 | t-test | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOK FM | RADIO MARYJA | |||||

| Joy | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 1,212 | 0.229 |

| Anger | 0.78 | 3,11 | 1,15 | 2,89 | -0.593 | 0.554 |

| Disgust | -0.41 | 1,06 | 0.44 | 1,49 | -3,171 | 0.002 |

| Surprise | 0.19 | 0.46 | 0.05 | 0.28 | 1,773 | 0.079 |

| Sadness | -0.85 | 6,98 | 1,54 | 5,84 | -1,787 | 0.077 |

| Fear | -0.18 | 0.41 | -0.06 | 0.15 | -1,906 | 0.60 |

| Question | Mean 1 | Standard deviation | Mean 2 | Standard deviation 2 | t-test | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOK FM | RADIO MARYJA | |||||

| Objective text | 0.63 | 1,59 | -0.36 | 1,72 | 2,979 | 0.004 |

| Valuable text | 0.59 | 1,61 | 0.16 | 1,54 | 1,364 | 0.176 |

| Credible text | 0.53 | 1,70 | -0.36 | 1,59 | 2,695 | 0.008 |

| Understandable/clear text | 1,86 | 1,50 | 1,56 | 1,85 | 0.878 | 0.382 |

| Emotion | Mean 1 | Standard deviation 1 | Mean 2 | Standard deviation 2 | t-test | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TVP INFO | TVN24 | |||||

| Joy | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.45 | 1,72 | -1,361 | 0.177 |

| Anger | 3,08 | 7,88 | 0.01 | 6,33 | 2,119 | 0.037 |

| Disgust | 0.14 | 1,21 | -0.48 | 1,01 | 2,676 | 0.009 |

| Surprise | 0.34 | 0.93 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 1,796 | 0.076 |

| Sadness | -1,78 | 4,14 | -1,35 | 2,93 | -0.583 | 0.561 |

| Fear | -0.05 | 0.37 | -0.07 | 0.15 | 0.405 | 0.686 |

| Question | Mean 1 | Standard deviation | Mean 2 | Standard deviation 2 | t-test | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TVP INFO | TVN24 | |||||

| Objective text | 0.04 | 2,06 | 0.54 | 2,02 | -1,216 | 0.227 |

| Valuable text | 0.08 | 1,88 | 0.64 | 1,68 | -1,559 | 0.122 |

| Credible text | 0.31 | 2,16 | 1,18 | 1,51 | -2,328 | 0.022 |

| Understandable/clear text | 2,27 | 0.97 | 2,44 | 0.81 | -0.968 | 0.335 |

| Emotion | Emotion | Emotion | Emotion | Standard deviation 2 | t-test | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUPER EXPRESS | NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC | |||||

| Joy | 0.05 | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.95 | -1,466 | 0.146 |

| Anger | 1,45 | 6,42 | 0.23 | 1,79 | 1,266 | 0.209 |

| Disgust | -0.29 | 0.70 | -0.47 | 1,24 | 0.909 | 0.366 |

| Surprise | 0.12 | 0.50 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.889 | 0.376 |

| Sadness | -1,17 | 3,37 | -1,27 | 4,23 | 0.125 | 0.901 |

| Fear | -0.09 | 0.21 | -0.11 | 0.24 | 0.416 | 0.678 |

| Question | Mean 1 | Standard deviation | Mean 2 | Standard deviation 2 | t-test | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUPER EXPRESS | NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC | |||||

| Objective text | 0.69 | 1,61 | 1,64 | 1,35 | -3,164 | 0.002 |

| Valuable text | 0.55 | 1,80 | 1,90 | 0.97 | -4,617 | 0.000 |

| Credible text | 0.16 | 1,82 | 1,68 | 1,35 | -4,709 | 0.000 |

| Understandable/clear text | 2,12 | 1,18 | 2,40 | 1,05 | -1,233 | 0.220 |

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

|

|

© the authors, 2019. Last updated: 14 December, 2019 |