Conceptualising welfare workers as information bricoleurs: theory building using literature analysis, organisational ethnography and grounded theory analysis

Introduction

What role can organisational ethnography and grounded theory analysis, combined with literature analysis, play in developing theoretical concepts to explain information practices in the welfare field? In a recent study, undertaken in a small community organisation in Victoria, Australia, these methods were used to good effect, enabling the development of the concept of information bricolage and the conceptualisation of welfare workers as information bricoleurs. The French term bricoleur refers to a handy man, who is skilled at using supplies to hand to build functional objects (Levi-Strauss, 1966). The traditional bricolage literature describes bricolage as the art of making something new using readily available materials and resources. Information bricolage came to be defined as ‘the engagement in fluid, unplanned, collaborative information practices, through the use or recombination of resources close to hand’ (French, 2014).

The pseudonym of the social services organisation, where the study was undertaken, is the Community Advice Centre (CAS). This centre employs welfare workers as well as using volunteers (unpaid staff), with backgrounds in fields as diverse as psychology, social work, counselling, case management, community development or nursing. Welfare work encompasses counselling, emergency financial assistance, community development, case management, and advocacy (Lyons, 2001).

Significance of the study

There is a paucity of research focussing on information seeking (including information use) in welfare work. Welfare literature emphasises the study of clinical skills, while paying little attention to the importance of the informational work that workers undertake every day, including assessing information needs of clients, seeking and evaluating this information, referring clients to other services, and sharing information with other workers (Parton and Kirk, 2010). Although there is an increasing expectation for welfare workers to be information mediators, this important role has not been widely investigated, either in the welfare or information science literatures.

The study is also significant because of its theoretical contribution. The concepts of bricolage and the related bricoleur are not new. Their application to enable a deeper understanding of a particular type of information practice is an original contribution to the field of human information behaviour. How this theory evolved will become clear as the paper develops.

Research questions

Questions relevant to this paper are:

- How has organisational ethnographic method (and associated techniques) enabled an in-depth exploration of the information practices of welfare workers in a particular setting?

- How has constructivist grounded theory data analysis, aided by literature analysis, enabled theory building and the conceptualisation of welfare workers as information bricoleurs?

The findings from the study are used to answer these two questions.

Literature review

The literature underpinning the choice of the term, information practices, begins the literature review, followed by a section on work practices, given their important influence on information practices. Further discussion of bricolage completes the review.

Information behaviour and information practice

Savolainen (2007) analysed the ‘umbrella concepts of information-seeking studies’, which he labelled as information behaviour and information practice. Information behaviour encompasses all aspects of human behaviour in relation to seeking and evaluating information, including identifying a need for information; selection of particular channels and sources; and the giving, sharing or use of information (Wilson, 1999a). With information practice, the emphasis is on shared meanings, referring to information-related practice that is firmly embedded in work and other social interactions (Savolainen, 2007). Although often seen as interchangeable with information behaviour, information practice draws on the social interactions of a community of practitioners, a sociotechnical infrastructure, and a common language (Talja and Hansen, 2006). While the discourse on information behaviour is mainly associated with the cognitive viewpoint, ‘… information practice is mainly inspired by the ideas of social constructionism’ (Savolainen, 2007, p. 109).

The term information practices was preferred over information behaviour for the study reported here, despite the fact that the underpinning research philosophy is not solely social constructionist. This is because information is embedded in welfare work and there is a strong social element in the way that information is used. In line with the definition of Talja and Hansen (2006), the term information practices is seen to encompass all aspects of welfare worker interactions involving information, including information seeking, retrieval, evaluation, synthesis and use, and verbal discussions of information. The way information is embedded in welfare work is strongly associated with work practices in a wider sense.

Work practices

Work place theory that acknowledges the complexity of work place practices includes Cox (2012) and Schatzki (2001). Work practices are seen as socially mediated, negotiated and collective rather than just relying on individual knowledge (Østerlund and Carlile, 2005; Schatzki, 2005). The concept of community of practice expands on this idea (Lave and Wenger, 1991).

The literature of work practices of welfare workers has often emphasised their fluid, improvisory nature (Ferguson, 2008, 2010), where information tasks merge with other work activities. Welfare work often involves building on prior knowledge (often tacit) of techniques and services, rather than engaging in intensive information seeking and evaluation (Day, 2007). Limitations of time and resourcing may add to the tendency of welfare workers to rely on what they know. Apart from information about what services exist, welfare workers need to process knowledge such as how a referral should be made, which services are suitable for a particular client, and which services are trustworthy (Sheppard, 1998; Westbrook, 2009).

The impact of work place complexities also emerges from research in the information behaviour field (e.g., Pettigrew, 1999; Solomon, 1997a, 1997b, 1997c; Iedema, Long, Forsyth and Lee, 2006; Lundh and Limberg, 2008; Lloyd, 2009). Solomon found that workers in his case study organisation did not consistently follow ordered information behaviour processes, but rather they were embedded in daily work practices. A blurring between information behaviour and work practices, such that workers do not discern a difference between them, has also been noted by Savolainen (2007). Workers often follow a messy and iterative path when engaging with information and knowledge, what Pescosolido, Gardner, and Lubell (1998) called muddling through. Any attempt to model information practices in a work context needs to capture the complexities, where particular systems may be involved and where the work required may result in a non-linear, iterative process of information use.

Bricolage

Bricolage rests, not on breakthrough innovations, but on gradual accumulation of knowledge about tools and materials, as well as an ability to re-use objects for purposes for which they were not originally designed (Baker and Nelson, 2005). For example, a bricoleur may use scraps of material to mend clothing.

The majority of research conducted to date has focussed on the development of technology rather than ideas (e.g., Garud and Karnøe, 2003). However, Levi-Strauss distinguished between examples of bricolage involving manipulation of materials and technology, and ‘bricolage on the plane of speculation’ (Levi-Strauss, 1966, p. 21), concerned with ideas and theories (Hatton, 1988; Levi-Strauss, 1966). Thus the original conceptualisation of Levi-Strauss (1966) can embrace resources to hand which may be physical objects, other people, but also conversations and the tacit knowledge of the bricoleur. Harper (1987) saw materials and ideas as often collected into a heterogeneous treasure trove of resources, forming the resource repertoire with which the bricoleur conducts a dialogue (Duymedjian and Ruling, 2010).

Research paradigm, methods and techniques

The constructivist (interpretivist) paradigm, drawing on both personal constructivist and social constructionist theories, provided the underpinning research philosophy. Personal construct theory is based on the belief that ‘people make sense of their world on an individual basis, i.e., they personally construct reality, with each person’s reality differing to some extent from another person’s’ (Williamson, 2013a, p. 11). Social constructionist theory places emphasis on shared meanings developed through social processes and language (Williamson, 2013a; Schwandt, 2000). Although not universally accepted, Crotty (1998) suggested that it is useful to use constructivism to refer to ‘meaning making constructed in the individual mind’ and constructionism to refer to the ‘collective generation and construction of meaning’ (p. 58). This conceptualisation was useful for the study, given that both individual and group perspectives were important. Since the individual welfare worker was the primary unit of analysis, personal construct theory proved useful for framing the data collection and analysis on how individual workers understood their own work and information practices. Social constructionism was a useful analytical frame to consider the sharing of meanings about work and information practices, and was particularly pertinent to the study of the collaboration and storytelling observed during the participant observation phase. In the context of health and welfare work, much information is constructed and evaluated through oral discussion and narrative (Aas, 2004; Närhi, 2002; Tsang, 2007).

Within this framework, the two related components of the method, in addition to literature analysis, were organisational ethnography and constructivist grounded theory analysis. The research was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Organisational ethnography

Ethnography emphasises deep understanding of a culture or a community through observing and participating in practices of daily life (Patton, 2002). A hall mark is the development of thick description (Geertz, 1973) from the data. Organisational ethnography is the application of ethnography to an organisational setting (Eberle and Maeder, 2011; Van Maanen, 2011; Watson, 2011). Although the method shares many features with traditional ethnographies of other cultural groups - such as developing a strategy for fieldwork which is responsive to circumstances, using participant observation and the writing of field notes - there is usually less cultural and geographic distance between the researcher and the participants (Eberle and Maeder, 2011). Organisational ethnography is useful for getting close to participants in their natural setting, actively interacting with them and sharing experiences (Watson, 2011). An ethnographic approach has been used in a few other studies focussed on information practices or information behaviour in a workplace setting, using participant observation as a technique. Examples include Pettigrew (1999) and particularly Solomon (1997a, 1997b, 1997c) which was a significant organisational ethnography of managers of natural resource conservation projects.

The organisation

CAS is a medium-sized community organisation which focusses on the provision of welfare services in a lower socio-economic suburb of Melbourne (Australia). The area also has considerable cultural diversity. CAS has a commitment to social justice, supporting clients from diverse backgrounds and providing information to support choices and actions.

The researcher worked, part-time, as a records manager in the organisation and was part of a small operations team. Although her work cut across all parts of the organisation, she did not work with other staff and volunteers as a fellow team member and therefore had sufficient distance to ensure an impartial approach.

The sample

The sample consisted of fourteen welfare workers (counsellors, case managers, social workers, psychologists and community development workers), all employees or volunteers at CAS. The two client participants had been attending CAS for support services for over six months and were invited to participate by their respective welfare workers. Welfare workers were recruited through information sessions, emails, and approaches via line managers. Generally sampling was opportunistic (Patton, 2002), with the majority of participants not being chosen to fit a particular purpose. Nevertheless the profile of participants was reasonably representative of CAS as a whole in terms of the cultural and professional backgrounds, work role, and years of experience.

Data collection

The fieldwork took place between October 2010 and July 2011. A range of typical ethnographic data collection techniques was used, including semi-structured interviews, participant observation, journaling and document analysis. The two key techniques – interviews and participant observation - are partly described in this section, with additional information provided in the findings section.

Interviews

Semi-structured interviewing was used as a data collection technique in the early stages of fieldwork, with eight interviews being conducted from October to December 2010. Interviews are effective in garnering participants’ viewpoints and perspectives, and to understand how they interpret their lives (Patton, 2002; Spradley, 1979). The list of interview questions was a broad guideline only, with participants being encouraged to explore other issues - a useful characteristic of semi-structured interviews, which allows for flexibility to pursue leads offered by participants (Williamson, 2013b). Topics covered ranged from demographics and CAS work role, to the viewpoints of participants on the nature and role of information practices. The latter included interpretations of the nature of daily work and where information practices fitted within it; the types of information and knowledge used day-to-day, and the role of technologies and associated bureaucratic procedures.

Participant observation

The term, participant observation, is often used synonymously with the term, ethnography, resulting in a complexity that is difficult to navigate (Williamson, 2013c). Here participant observation is used as a fieldwork technique and, as such, is a key component of many organisational ethnographic studies (Eberle and Maeder, 2011). Few researchers these days go native and become integrally involved in the daily lives of their study participants. Rather, there are several ways in which modern participant observation is conceptualised and practised (Williamson, 2013d). For example, one conceptualisation is that of insider/outsider, where the researcher may alternate between insider and outsider roles, or experience both simultaneously (Spradley, 1980, p. 57). Another is of the researcher role fluctuating from that of observer removed from involvement in activities under observation, to being a full participant in those activities (Van Maanen, 2011). Glesne and Peshkin (1992) described the researcher role on a four-point continuum, from complete observer to complete participant, with flexibility for the researcher’s roles to change during the course of a study. This was the approach of the present study in the remaining seven months of field work (to the end of July 2011). There were seventeen sessions of participant observation , typically lasting between two and three hours duration (thirty-six hours in total) and involving all fourteen workers and two clients.

Grounded theory analysis

Data analytic techniques, drawn from grounded theory methods, were used as a thorough way of coding and analysing the data, and generating theory. Grounded theory has evolved through various approaches (e.g., Glaser andStrass, 1967; Strauss and Corbin, 1998). Charmaz (2006, 2009) who is regarded as a second-generation grounded theorist (Morse, 2009), outlined a constructivist approach to grounded theory. Because Charmaz’s constructivist philosophical underpinnings mesh well with the constructivist paradigm used for the project, her version provided the primary guiding framework. It is important to note that the project used grounded analysis, rather than grounded theory where theory is built from the ground up. Grounded analysis was used to draw theoretical ideas from the data, which were then linked with ideas from literature to enable the development of a substantive theory (Urquhart, Lehman and Meyers, 2010). The following is a brief outline of the analysis.

- Data were generally transcribed and analysed after each day of fieldwork, with initial coding influencing who and what were observed and resulting in slight question variations.

- Incident by incident coding was used for interview and observations (task by task).

- Focussed coding was done through conceptual mapping (mind maps) and memos.

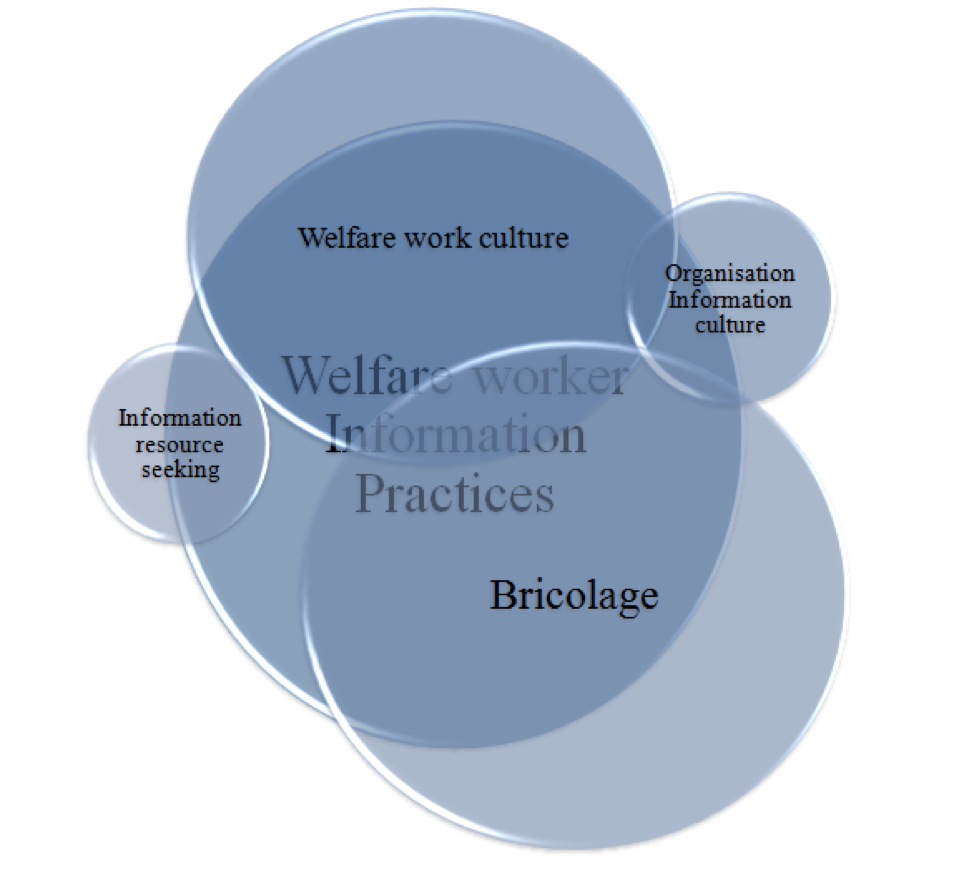

- Theoretical coding was done through theoretical memos, concept maps, comparative tables and Venn diagrams of key concepts.

- Constant comparison occurred at all stages of fieldwork and data analysis. Responses were compared across participants and also across components of data collection, e.g., interviews and participant observation sessions.

- Theoretical sampling was used at later stages of the participant observation. For example, identification of instances of collaboration between workers led to selection of participants who were working together on common client issues.

- Memos were used extensively for theory building.

Findings

The goal of this section is to illustrate: (1) how organisational ethnographic method (and associated techniques) enabled an in-depth exploration of the information practices of welfare workers at CAS; and (2) how literature analysis, along with Charmaz’s constructivist grounded theory data analysis techniques, enabled the conceptualisation of information bricolage.

The information practices of welfare workers: the lens of organisational ethnography

Organisational ethnography, in line with ethnographic methodology as a whole, has at its heart the immersion in life worlds of particular groups (Prus, 1997). An understanding of welfare work practices was key to beginning to understand information practices, the latter being subsumed within the former. It was therefore important that an extended period of time be spent observing work processes at CAS, in depth, and also in learning about how workers, themselves, interpreted their roles. Ethnographic fieldwork provided opportunities to develop pictures of externally observable behaviours, as well as to try to gauge internal states, such as worldviews, values, opinions and interpretations (Patton, 2002). Each research technique, especially the semi-structured interviews and participant observation, allowed for exploration of different aspects of work practices and information practices at CAS.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews allowed the researcher to get to know participants, beyond the cursory acquaintance acquired through her work in the organisation. This included their views on information and its place in their work. Interviews enabled the understanding of the meaning that welfare workers attributed to what they were doing (Watson, 2011). They provided the space where the language of welfare work was revealed in the study, with many of the terms later becoming codes and analytical labels for further theoretical consideration. Some of these initial insights into the nature of work, along with participants’ understanding of their roles, shaped and changed the focus of the research. For example, welfare workers often talked of the support (possibly including information provision) that they needed to provide clients, as this interview excerpt with H, intake worker, illustrates.

RF: So how do you go about finding information to answer questions, where you don’t know the answer?

H: Well, I find that I know the answers to most questions, even if sometimes I have to go away and think about it, or talk to my team. … May be it turns out that the person is asking you where Centrelink is because they don’t know how to get them to listen to them, or can’t read the form. … When I really don’t know, I might ask around, or every now and then look at the Internet. I really don’t use the Internet very often though, as many of the organisations we work with don’t have great websites, or our clients have poor literacy and English language skills. Even if I use it myself to find out, I have to adapt what I find to suit the client.

The substantial amount of time spent in support, particularly in indirect support (i.e. not in direct contact with a client but completing tasks of benefit to them), was an insight that led to change in the focus of participant observation: from worker-client interactions only, to also exploring the nature of indirect support and the role of information as part of it.

One further interesting insight from the interviews was what was not articulated. Participants could not fully describe how information fitted into their practice because of the synthesis of information within wider work practices. Participant observation was therefore crucial in unpacking the reality of welfare work in this context.

Participant observation

Participant observation as a research technique allowed for study of the culture of the organisation and comparison of particular work practices across CAS (Eberle and Maeder, 2011). Along with the semi-structured interviews, participant observation enabled extensive exploration of welfare work tasks and how they fitted into the rhythm of a typical work day, as well as the role of information practices. Key findings concerned the fluidity of information practices and the nature of welfare workers treasure troves of resources.

In this project it was most useful to think of participation as operating along a continuum (Glesne and Peshkin, 1992). During the observational sessions, the researcher moved from more to less participation depending on the practice being studied and the needs of the situation. For example, there were times when the researcher was drawn into discussions of services which might be useful for particular clients. There were also instances where the researcher withdrew to far more unobtrusive observation, particularly when a worker was telephoning a service or client. The advantage of taking a continuum approach to participant observation is that it allowed for a natural interaction, where clarifying questions could be asked. Thus there was no false distance between researcher (RF) and participant which, given the pre-existing working relationship, would not have been possible.

Fluid practices

Data from observations revealed a range of typical welfare work tasks, from those that were focussed on supporting clients to those that were framed as administration and reporting. However an ordered process - of assessment, planning, implementation, coordination, monitoring and evaluation (Case Management Society of America, 2012; Cohen, 2011; Kuhn et al., 2012) – did not emerge. While process steps were sometimes mentioned, e.g., an interviewee talked of asking clients about their issues (an example of client needs assessment), observational data showed that workers actually merged steps. They moved between different tasks, or proceeded with multiple tasks simultaneously, as the literature of work practices of welfare workers has emphasized (e.g., Ferguson, 2008; 2010). Observations of A and D, case managers, illustrate this point.

A enters data on a spreadsheet for five minutes. He leaves this open, while he looks up a telephone number - for a school - from a case management system, and then picks up the phone to call. D enters the room.

A: Hey D, I was just going to ask you about that new program at the swimming pool for Muslim women – what day is it on, and where do you sign up?

D: It’s on Tuesdays and you can call if you want, or your client can just turn up.

A: Thanks.

A turns back and dials number. While he is waiting, he adds a few more numbers into his spreadsheet.

In keeping with work place theory (Cox, 2012; Schatzki, 2001), the welfare workers in these examples moved fluidly between different tasks for different clients. They were frequently observed to interrupt tasks to speak to colleagues, clients or telephone contacts. After interruptions, they sometimes returned to the original task, or perhaps began another. Tasks could be completed on behalf of one or many clients, or workers could switch between administrative tasks and client-focussed tasks. Information tasks, such as asking for relatively simple information like dates or contact numbers; or more complex tasks, such as requesting advice and discussing a collage of information resources to provide an appropriate service response, were not observed to follow an ordered information behaviour process. The blurring of processes and boundaries was an observation made by Savolainen (2007) and Solomon (1997a, 1997b, 1997c) who found that information behaviour (or information practices) were embedded in daily work practices. Clearly workers were following a messy, iterative path or muddling through (Pescosolido, Gardner and Lubell, 1998). Information behaviour was non-linear and workers had a variety of preferences and ways of working.

Welfare workers’ treasure troves

If welfare workers needed information, their observed preferences were for oral communication. This aligns with Lloyd’s (2009) research where information practices in a work setting were found to be socially mediated, within a community of practice (Talja andHanson, 2006). When participants used paper-based resources, they were usually drawn from personal collections of information resources. They were observed to routinely draw on their own knowledge of community services and the issues of previous clients, together with their understanding of daily work practice. In this way they found the best information fit for a client, as illustrated by the observation of E, youth worker.

E: I just need to look up the contact details for [housing service] so I can give them a call.

E gets out a ring binder full of typewritten pages and leaflets. She goes to the front page and runs her finger down an A4 sheet with names of services and telephone numbers listed.

RF: What is that folder?

E: Oh, that’s my box of tricks [laughs]. It’s actually my resource folder. I have all the info I tend to use a lot here, some of it is pamphlets and stuff, but I have also made my own list of contacts, which is probably the thing I use the most.

RF: So is it mainly service information?

E: Yeah mainly, but I do have a few checklists and procedures to remind me of how to do some things, like complete the data forms.

RF: I like that name, box of tricks. Why do you call it that?

E: Not sure really, maybe because sometimes in this job you have to be a magician, and this folder helps me do the magic.

Just as E disclosed, many of the welfare workers in this study referred to sets of resources that they used regularly as their box of tricks, bringing to mind the heterogeneous treasure trove of resources, forming the resource repertoire of the bricoleur (Duymedjian and Ruling, 2010). In some cases this was a folder or filing cabinet, but it could also be lists and diagrams kept beside the telephone or as posters on the wall. In the information and referral team room, where volunteers and staff shared office space, the resource binders were shared.

Thus observational sequences enabled insights into how tasks intertwined knowledge, information and work practices and tools in fluid sequences. Strongly rich themes emerged from the fieldwork data. However, the data analysis and theory building techniques in organisational ethnography were less useful, and are often not made explicit in descriptions of ethnographic studies. Grounded theory analysis was therefore a critical tool for synthesising themes.

Theory building through literature analysis and grounded theory analysis

The process of theory building, from the data collected using ethnographic method, was underpinned by literature analysis and grounded theory analysis. Extensive reading of the literature occurred prior to and during the field work period, meaning that, while the analysis tools of grounded theory were used, the study was not, itself, a grounded theory.

Although time-consuming, grounded theory analysis is useful for synthesising and making sense of large amounts of data. Grounded theory analytic techniques provide clear instructions, e.g., how to move from codes to memos to models/ frameworks, but also emphasise the importance of going back to the data and back to the field. As described above, the techniques were drawn from constructivist grounded theory methods (Charmaz, 2006). Since space limitations do not allow detailed discussion of the tools, emphasis will be on ways in which they were used to assist theory building.

Literature analysis

One of the criticisms of grounded theory method is that it is difficult to scale up theoretical ideas into substantive or formal theory which can be integrated with other theories in the field. This potential limitation can be overcome by explicitly linking or integrating the emerging concepts with theory from the relevant discipline (Urquhart, Lehman and Meyers, 2010). While a critical review of information behaviour and information-seeking models, extant in the literature, was originally undertaken, overarching key theories from elsewhere were also reviewed, along with the work of key thinkers. Authors such as Giddens (1984), Polanyi (1966) and Levi-Strauss (1966) played a key role in theory development. In particular, the concept of bricolage seemed to be potentially useful, given how the welfare literature describes the work of people employed in the field, confirmed by the researcher’s own experience of working in the sector. While this process sounds smooth in retrospect, there was actually much time spent struggling to see the connections between sometimes very different theoretical areas.

The role of analytic tools

The tools that aided theoretical development were memos, mind maps, and Venn diagrams. Memos played a vital part in the linkage between data and theory, and enabled testing and development of ideas (e.g., relating to bricolage). They became increasingly theoretical as time progressed and included tables used to structure thoughts. For example one memo, in the form of a table, compared elements of bricolage from the literature with those seen in the research field data and confirmed exemplars of bricolage-like behaviour in the field. (French, 2014).

Mind maps, plotting key points, were very important in understanding issues that were emerging in the data but which had not been seen, initially, as important. For example, the theme of the importance of storytelling emerged in initial interviews. A mind map helped to highlight the importance of this concept, resulting in three observation sessions, focussed on open spaces and workers collaborating in their support work for clients. Observing these sessions increased the likelihood of the researcher observing worker interactions and story telling, given that a significant proportion of time was involved in narrative and explanation. These sessions seemed to suggest an oral culture.

Venn diagrams and, later, more developed theoretical diagrams became important as the analysis progressed. These were a very useful way of seeing the range of key concepts. They had the added advantage of being very useful communication tools when discussing theoretical ideas with others. Figure 1 is a Venn diagram created at the mid-point of the data analysis phase. As indicated by the relative size of the circles, by this time the influence of particular factors on welfare worker information behaviour was becoming clear.

Figure 1 explores the relationship between welfare worker information behaviour (shown in the central circle) and four key themes that had been identified. Examples of workers engaging in bricolage (fluid, unplanned, collaborative information practices) were frequent, as seen by the positioning of the bricolage circle over the top of the central circle. Since there were far fewer instances of information resource seeking, where a worker actively searched for new information resources, this circle is small in size. The culture of the welfare professions was also influential, with the presence of an oral storytelling culture impacting on the type of information practice observed (e.g., the sharing of information through talking to colleagues rather than use of Internet searches). The organisation’s information culture seemed to have a lesser impact, with only minimal influence and use of organisational procedures and business systems in daily work. Bricolage and welfare work culture influenced each other, as shown by the overlap between the two concepts in the figure.

Conclusion

Literature analysis, together with an ethnographic approach and grounded theory analysis, allowed for significant insights into the fluid nature of information and work practices of welfare workers in a small community organisation in Australia. The framework for the study drew on social constructionist, as well personal constructivist ideas, to capture both shared and individual perspectives of welfare workers. It was found that these workers did not follow a predictable sequence of tasks and steps in their information practices, but rather relied on their box of tricks including personalised information resources, stories and support from colleagues, and their own knowledge to determine the best approach to meet the needs of clients. The model of information bricolage, which provides a broader perspective on information practices, is in stark contrast to models of information behaviour which focus on structured searching for new information (Case, 2012; Pettigrew, Fidel, and Bruce, 2001; Wilson, 1999a, 1999b). In particular, the information bricolage model fits well with the fluidity of information practices as embedded in the daily practice of welfare work. See French and Williamson (in press), for the model of information bricolage as well as discussion thereof.

Organisational ethnography, with its semi-structured interviews and participant observation, had great strength as it allowed for a deep investigation of the daily activities and embedded information practices within them, processes that were tacit to workers. The result was vivid insights into work practices described in the language of welfare workers. Insights from interviews often provided the initial codes and themes which were further explored in participant observation sessions. Because participant observation was seen to operate along a continuum, the researcher was able to adjust interactions to suit the needs of the situation, thus allowing for a natural, organic interaction and more nuanced insights than through non-participatory observation alone.

Grounded theory analysis, together with literature analysis, provided the ability to build theory through ongoing interaction between insights from the data and literature. Analytic tools such as mind maps and Venn diagrams allowed for development of themes into more cohesive conceptualisations that could then be incorporated into a series of models on information bricolage in welfare work. Especially where research draws on multi-disciplinary perspectives, it can be difficult to surface and crystallise concepts from the literature and relate them to findings as they emerge from the data analysis. The techniques of diagramming particularly assisted in deciding where links were appropriate. For example, the potential of the bricolage literature to provide the key concept to explain the findings of the research was resolved through a series of diagrams and figures, over a period of months.

The combining of techniques of two complementary qualitative research methods (along with the literature analysis) allowed for numerous insights into welfare work that may have applicability to other health and community disciplines. Researchers and practitioners interested in information practice and information behaviour may find that this combination of methods allows for new insights and offers a useful way to draw on disparate disciplines, building multi-layered concepts which can be developed into robust theoretical models.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on Rebecca French’s doctoral thesis, of which Kirsty Williamson was a supervisor. The authors would like to thank the other three supervisors, all staff at Monash University, Australia: Professor Frada Burstein, Associate Professor Graeme Johanson and Dr Kerry Tanner.

About the authors

Rebecca French completed her Master of Information Management and Systems at Monash University in 2007, after employment as a psychologist for 10 years. She completed her PhD at Monash University’s Faculty of IT in 2014 while working as a Researcher and Records and Information Management consultant with health and welfare organisations. Her doctoral research focussed on information practices, bricolage and knowledge sharing by health and welfare workers. Her research interests are in the areas of information practices and recordkeeping in health and welfare organisations. Since February 2014, she has worked as Information Coordinator at the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation. She can be contacted at: rfrench@vichealth.vic.gov.au. Her mailing address is: Dr Rebecca French, Information Coordinator, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) 15-31 Pelham Street, Carlton VIC 3053, Australia.

Kirsty Williamson received her Master of Librarianship from Monash University and her PhD from RMIT University, both Australian universities. She is now Adjunct Senior Research Fellow at Monash University’s Caulfield School of IT and Charles Sturt University’s School of Information Studies, having headed Information and Telecommunications Needs Research for many years (affiliated with both universities). She has undertaken many research projects, funded by a range of different organizations including the principal funding body of Australian Universities, the Australian Research Council (ARC) and also has a strong ‘publication’ track record. Her principal area of research has been ‘human information behaviour’. Many different community groups have been involved in her research, including older people, women with breast cancer and online investors. She can be contacted at: kirsty.williamson@monash.edu. Her mailing address is: Dr Kirsty Williamson, Caulfield School of Information Technology, Monash University PO Box 197, Caulfield East, Vic., 3145.