Twitter conversation dynamics of political controversies: the case of Sweden's December Agreement

David Gunnarsson Lorentzen

Introduction

The outcome of the Swedish parliamentary election in September 2014 created a political crisis. In December 2014 it was decided that a re-election would be held in March 2015 after no party or constellation of parties had won majority. For the first time in several decades a budget proposition failed to generate enough support in the Parliament. At the end of 2014 it was revealed that an agreement had been reached between six parties. This settlement, named the December Agreement, was created to make sure that a minority constellation could succeed with its budget propositions. The political crisis and the agreement sparked an intense debate on Twitter, thereby enabling an interesting material for investigating the development of political controversy. The December Agreement was an extraordinary event opening up for grassroot discussions on the character of deliberative democracy. It is, therefore, suitable for investigation of political controversies on Twitter. This would seem to be an ideal case in order to study how people with different ideological viewpoints interact on Twitter.

The methodological approach to controversies on Twitter in the current study builds on the assumption that what is important for understanding the conversation dynamics is not to what extent conversational tweets occur in a defined conversation, but rather the tweets that are conversational. The use of a hashtag makes it possible to assign one or more keywords to a tweet and, by doing so, adding the tweet to an ongoing conversation. The hashtag makes it easy for the researcher to follow what is posted on a given subject and also makes data collection from a research point of view trivial. But by utilising such an approach, the follow-on communication, comprised of tweets replying to hashtagged tweets without including the hashtag, is not captured (e.g., Bruns, 2012). The follow-on communication has so far been largely overlooked in Twitter research (e.g., Bruns and Moe, 2013).

By utilising a dataset including follow-on communication around a set of hashtags, the focus of this paper is to analyse conversation threads in relation to the December Agreement. The inclusion of follow-on communication yields numerous opportunities for research, of which three are investigated in this paper. First, it makes it possible to analyse the different phases of threaded discussions. Secondly, as Twitter facilitates a mechanism for invoking politicians and other actors into a conversation by mentioning them (e.g., Bruns and Highfield, 2013), the potential reaction from the invoked user can be studied. Finally, the existence of echo chambers, i.e., groups of like-minded who mainly talk to each other (e.g., Sunstein, 2009), can be fully studied. Apart from filling a gap in previous Twitter research, this study gives insights into the interchanges between different actors in political communication on the platform. An understanding of how Twitter is used is crucial for those who are interested in either using the platform for communication or analysing sentiments and opinions expressed.

The discussions on Twitter spurred by the December Agreement involved political controversies with several interesting traits. Among these we identify the dynamics of three political blocks, a strong focus on the migration issue and conflicts on whether it is reasonable to have the December Agreement. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the lifecycle of controversy conversations on Twitter in relationship to a political event, focusing on conversation dynamics, initiation, development and closure of conversations and participants and participation. Given Twitter's communication model where a reply from user A to user B appears in the timeline of user C if C follows both A and B (Twitter, 2015) and a reply from A to B seems to appear in a search result if C follows either A or B, directly or transitively, I am interested in how threads that spark controversy develops. The overarching research question is How do the controversy conversations evolve following the December Agreement?

The debate covered in this study consists of Swedish political conversations and the controversial stage is this sudden event, the December Agreement. The study sheds some light on how threaded conversations evolve and what can be learned from them, as well as it provides an example of how to analyse threaded conversations on this platform.

Background

The analysis takes off from the two perspectives: controversy studies (e.g., Mazur, 1987; McMullin, 1987; Sismondo, 2004) and the political problem of polarisation through digital tools (Sunstein, 2009). Controversy studies aims for an understanding of how debates are terminated (Sismondo, 2004). During these debates, participants are trying to find and expose potential weaknesses in the arguments of the opponents (Mazur, 1987; Sismondo, 2004). Termination can be achieved in different ways: resolution, meaning that the controversy is solved through some kind of agreement, closure, which is the lack of agreement, and abandonment, where the participants eventually lose their interest (McMullin, 1987).

I borrow a model of controversy from Mazur (1987, p. 269). This includes two sides of a controversy; the establishment and the challenger. In between are the mass media reporting events and influencing opinion. Seen in this way, struggles over opinion are skewed in regards to power. Challengers are pushing debates on controversial issues in order to gain more recognition and even out the asymmetrical power structure. Members of the establishment are, on their part, concerned with maintaining the status quo. In this case the establishment is comprised of the Red-Green coalition (the Social Democratic Party and the Green Party) and the Alliance (the Moderate Party, the Christian Democrats, the Liberal Party and the Centre Party). The main challenger is the far right nationalist party Sweden Democrats, a party that emphasises tougher immigration policies and consistently engages in debates over any related issue. The Sweden Democrats were not part of the December Agreement.

Related to this is the issue of polarisation and echo chambers that have been recognised as features of digitalised political communication. According to Sunstein (2009, p. 76), society might be better off 'if greater communication choices produce greater extremism' because 'when many different groups are deliberating with one another, society will hear a far wider range of views'. From such a vantage point, it is interesting to investigate if polarisation might increase or decrease following interactions on Twitter.

Are controversies really manifested and played out on Twitter? This issue is linked to the question of whether or not Twitter usage is conversational. It has been argued that the message types mention and retweets are fundamentally conversational (e.g., Bruns and Highfield, 2013). To some extent, this can be measured as the mention, used to either direct a message to a specific user or notify or invite other users of and to a conversation, was found to be directed in 91% of all the instances in one study (Honeycutt and Herring, 2009), while in another study it was mostly used to talk about people rather than to them (Bruns and Highfield, 2013). Similar conclusions were drawn by Mascaro and Goggins (2015), identifying initiatives to conversation in every fourth analysed replying message. Previously, it has been shown that political tweets are largely of the one-way communication type (e.g., Grusell and Nord, 2012; Small, 2011; Sæbø, 2011), but also that politicians might benefit from Twitter usage (e.g., Kruikemeier, 2014; LaMarre and Suzuki-Lambrecht, 2013). The latter conclusion can be contrasted with Yardi and Boyd's statement 'Twitter is hardly a medium for deliberative democracy' (2010, p. 317), a sentiment echoed by other researchers (e.g., Bozdag, Gao, Houben and Warnier, 2014; Trilling, 2015). Overall, different conclusions have been made regarding to what extent political conversations are played out on the platform.

Literature review

This section is divided into two parts. As research on political Twitter usage is, seemingly, dominated by media and communication studies and political science, the first part is centred on informational aspects of online communication. The second part has its focus on, for this paper, relevant aspects of political Twitter usage and communication.

Informational aspects of online communication

Burnett (2000) described a typology for analysing discussions in virtual environments, differing between non-interactive (e.g., lurking) and interactive behaviour at the broadest level. The interactive behaviour was further divided into hostile and collaborative behaviours. Testing this typology on two online communities, Burnett and Buerkle (2004) focused on hostile interactive behaviours, collaborative non-informational interactive behaviours and collaborative informational interactive behaviours. It was suggested that the typology could be revised with considering category limits and ambiguities, the temporal dimension and definitional limits.

Savolainen (2015) focused on emotion in information sharing by analysing conversation threads discussing immigration in an online discussion forum. Among the findings was the prevalence of neutral statements although disagreement was more common than agreement. Another discussion forum study of relevance was made by O'Connor and Rapchak (2012), who analysed 226 threads in three forums discussing a health care reform. Use of sources was rare, quite often biased and citations were sometimes challenged by participants. The authors found that misattribution was common, for example opinions expressed in blog posts or in comments in relation to the content cited as formal information.

The conception of Twitter as a microblog indicates that there are aspects that can be transferred from blogging. In Savolainen's (2011) study of interaction between bloggers and blog readers on the topic of weight loss, bloggers seemed to be more inclined to share information rather than seek information. Agreement was more common than disagreement among the comments on the blogpost, which could roughly be translated to replies to a tweet. Disagreement was more common in blogposts, but overall disagreement was not common. Giving information or opinion was far more common than requesting, and more common in blogposts than in comments. In the Twittersphere, similar usage of a hashtag was identified by Small (2011). In her study, the hashtag was very much used for informing but also included opinion commentary in slightly more than 10% of the tweets analysed.

Mascaro and Goggins (2015) studied Twitter usage in conjunction with a political televised debate. Spreading information through retweets was common, but while the participants did use the mention feature to participate in conversations, the level of engagement was found to be low. Similarly, in an election campaign study of political candidates' usage of the platform, Graham, Broersma, Hazelhoff and van't Haar (2013) found that every fourth tweet sent by a candidate was interactive. Nonetheless, there were few examples of extended discussions. Attacking or debating with another user was the most common interaction type, followed by acknowledging a person or organisation.

Heverin and Zach (2012) discovered a few sense-making themes in their study of Twitter communication in relation to three crises. The themes were information sharing, information negotiation (conflicting information posted and clarification needed), information seeking, talking cure, sharing individual actions, understanding the 'why', contemplating awareness outside the local setting, and questioning the outcomes of the crisis. Elsewhere, information sharing has been found to be dominated by online information, followed by retweets and news (Small, 2011). Information diffusion on Twitter in the form of retweets has been identified in different contexts, for example in political linking behaviour (Dyagilev and Yom-Tov, 2014), during disasters (Sutton et al., 2014) and during protests (Tinati, Halford, Carr and Page, 2014). To Boyd, Golder and Lotan (2010) such information behaviour is a type of conversation. Contrary to this, the present study views the reply as conversational. With Burnett's (2000) broadest categorisation of information behaviour in virtual communities in mind (non-interactive and interactive), the present study takes the view that tweets not directed to anyone in particular (i.e., singletons) could be intended for both informing and initiating conversations.

Aspects of political Twitter usage and communication

Although there has been a lack of studies devoted to political controversies on Twitter, there are many examples of studies of different political aspects on Twitter, such as political actors' usage (e.g., Grusell and Nord, 2012; Kruikemeier, 2014; LaMarre and Suzuki-Lambrecht, 2013; Larsson, in press; Larsson and Ihlen, 2015; Sæbø, 2011), usage pattern of a political hashtag (e.g., Larsson, 2014; Small, 2011), elections (e.g., Bruns and Highfield, 2013; Larsson and Moe, 2012), polarisation (e.g., Bozdag et al., 2014; Conover et al., 2011; Lorentzen, 2014; Yardi and Boyd, 2010) and Twitter conversations in conjunction with events such as TV debates and protests (e.g., Jungherr and Jürgens, 2014; Kalsnes, Krumsvik and Storsul, 2014; Mascaro and Goggins, 2015; Trilling, 2015). Typically, Twitter activity increases during political events (e.g., Bruns and Highfield, 2013; Jungherr and Jürgens, 2014; Larsson and Moe, 2012). Jungherr and Jürgens (2014) also found that the distribution of type of tweets changed during the protests as the share of conversational tweets decreased. Mascaro and Goggins (2015) made similar findings with an increasing conversation level before rather than during the debate.

Evidence of politicians benefitting from Twitter usage, specifically by engaging with other users on Twitter instead of merely informing, has been presented (Kruikemeier, 2014; LaMarre and Suzuki-Lambrecht, 2013). While interaction between politicians and citizens does not seem to be common according to the Twitter research so far, both Ausserhofer and Maireder (2013) and Larsson and Ihlen (2015) have discovered examples of such communication. However, in the latter case the interactions were characterised by echo chambers as few citizens interacted with more than one party leader. There have been some contrasting views on whether the conversations are dominated by elite users such as politicians and mass media actors. Lorentzen (2014) explored political conversations that appeared to be dominated by citizens and similar findings were made by Small (2011). Other studies have reported that activity is dominated by citizens but attention more often given to politicians, experts or media actors (e.g., D'heer and Verdegem, 2014; Larsson and Moe, 2013). Larsson and Moe (2012) and Ausserhofer and Maireder (2013) both found a domination of elite users, however, in these two cases the focus was on a smaller number of users than in the studies of Small (2011) and Lorentzen (2014).

In the debate study by Trilling (2015), Twitter users had the potential of affecting the topics of the debate but there was also a dominance of sarcasm and attempts at humour. There was also a tendency that the Twitter conversations were more likely to highlight negative aspects. Mascaro and Goggins (2015) found interactions between the moderator of the debate and the Twitter users, which indicated that Twitter could function as a way to get involved in the debate. In another debate related study, Kalsnes, Krumsvik and Storsul (2014, p. 325) concluded that 'Twitter users scrutinize the agenda set by mainstream media and the politicians, and the discussion about the debate is equally present as discussions about the political topics of the debate'.

Polarisation on Twitter is visible in retweet networks (e.g., Bozdag et al., 2014; Conover et al., 2011; Dyagilev and Yom-Tov, 2014; Lorentzen, 2014) but not in mention networks (e.g., Conover et al., 2011; Lorentzen, 2014). Lorentzen (2014) also found evidence of polarisation in followership networks, but concluded that the lack of follow-on conversation, which is missing in all of these studies, might distort the mention network. Yardi and Boyd (2010) focused on a content analysis of abortion issues and found that participants were exposed to different viewpoints but also that there was a lack of meaningful discussion.

As indicated above, most of the Twitter studies have used limited datasets, not including follow-on communication. The one example is provided by Zubiaga et al. (2015) who proposed a method for collection of conversations around rumours. This was done by identifying the most retweeted tweets with a given hashtag or keyword, developing a schema for coding tweets in the conversations emanating from these tweets. The present study aims to bridge this gap in the literature by focusing on the conversation threads emanating from tweets including one of a set of hashtags related to a political event, and so avoiding the risk of analysing tweets outside their conversational context. A thread is defined as a chain or tree of tweets tied together by the reply metadata field (in_reply_to_status_id_str) which includes an identifier of the tweet a given tweet is replying to. A thread is then comprised by one singleton tweet and a set of replies to that tweet and to the replying tweets.

The study picks up on some suggestions for research. Specifically, it makes use of semantic analyses of mentions (Bruns and Highfield, 2013), combines quantitative and qualitative methods (Larsson, 2014; Larsson and Moe, 2013) and investigates if polarisation can be detected with the inclusion of follow-on communication (Lorentzen, 2014). Even though polarisation might not be evident in a mention network, the participants may very well keep holding on to their viewpoints despite being exposed to different viewpoints. In this paper, I not only turn my attention to structures and patterns, but also analyse the individual threads.

Method

Data set

The data set consists of 177,847 tweets which were posted by 16,349 users. In short, data were collected by simultaneously collecting tweets matching a set of hashtags and following the activities around the 5,000 most active participants in the conversation, using the streaming API for both (see Lorentzen and Nolin, in press). By doing this, follow-on communication related to the collected tweets was captured. With this data set, one limitation follows in that the data collection started a couple of hours after the press conference. Hence some relevant threads are missing.

All hashtags were related to the election, the December Agreement and general Swedish political conversations (Table 1). Tweets to the followed users were collected if they were replies to any tweet in the database or if they included any of the hashtags. Tracking the most active users in the dataset was a necessary methodological choice. It is possible that a reply to a tweet in the database is not collected if it is posted by someone outside the tracked group to someone else outside the tracked group. However, there are numerous examples of studies where up to a few thousand users are posting a large majority of the tweets and previous research has also shown that the least active users are also the least conversational (e.g., Bruns and Highfield, 2013; Bruns and Stieglitz, 2013; Lorentzen, 2014).

| Hashtag(s) | Description |

|---|---|

| #svpol | Swedish politics |

| #dinröst | Your vote |

| #val15, #val2015 | Election 2015 |

| #extraval, #extraval15, #extraval2015 | Extra election 2015 |

| #nyval, #nyval15, #nyval2015 | Re-election 2015 |

| #dö, #decök, #decemberöverenskommelsen | The December Agreement |

Sampling threads

In total, 13,193 threads starting after the press conference with volumes between 2 and 476 (median: 3; mean: 6.173) tweets were captured. The number of participants ranged from 1 to 194 (median: 2; mean: 3.345). 337 threads included just one user, most of these chains of tweets that were part of a longer message. More than half of the threads, 7,304, met only minimal standards, including only the initial post and one comment. For identifying possibly information rich threads and still having the possibility of categorising all the participants, a simple criterion was used. Threads with an arbitrary minimum number of ten participants and a minimum volume of 20 tweets were kept for closer analysis. Due to the usage of more general hashtags, such as #svpol, threads discussing other topics than the December Agreement were captured. Table 2 shows the number of threads discussing the December Agreement versus all threads meeting the volume and participants criteria. Discussions of the value of the agreement dominated the threaded conversations during the first few days.

In the second phase of the sampling, threads not discussing the chosen topic were excluded, resulting in 61 threads involving 930 unique tweeting participants who posted a total of 3,472 tweets. In total, 1,018 users were involved in these threads, but as 7 of them were suspended or had their accounts closed before the analysis of profile data, the analysis includes 1,011 users. Of the 3,472 tweets, 442 included at least one of the tracked hashtags. The 61 threads are summarised in table 3 with the attributes volume, number of participants and velocity (number of tweets per hour). A final, stratified sample was made to cover a range of threads with different volume, number of participants and velocity. This sample of ten threads was selected for qualitative content analysis.

| Day | Topical | Total |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 34 | 39 |

| 2 | 9 | 18 |

| 3 | 7 | 25 |

| 4 | 5 | 15 |

| 5 | 1 | 6 |

| 6 | 2 | 23 |

| 7 | 1 | 32 |

| 8 | 1 | 34 |

| 9 | 0 | 11 |

| 10 | 0 | 12 |

| 11 | 0 | 13 |

| 12 | 0 | 30 |

| 13 | 0 | 17 |

| 14 | 1 | 11 |

| Volume | Participants | Velocity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Min | 20 | 10 | 0.11 |

| 1st Q | 26 | 12 | 0.86 |

| Median | 35 | 18 | 1.52 |

| Mean | 56.92 | 24.2 | 3.54 |

| 3rd Q | 70 | 24 | 4.08 |

| Max | 314 | 194 | 19.62 |

Data analysis

A combination of descriptive statistics and content analysis was used to study the threads. In the first step, the overall life cycle of the conversations and characteristics of the threads discussing the December Agreement were outlined. In the second step, ten threads were sampled for qualitative content analysis focusing on the identified phases sparking of conversation, development and dynamics of conversations, and closure. Qualitative content analysis is an inductive process which 'may yield testable hypotheses but that is not its immediate purpose' (White and Marsh, 2006, p. 34). The process consists of four steps: 1) define research question(s), 2) sample the units (threads) which enables complete and accurate answers to the questions and present the big picture, 3) identify significant concepts and patterns, and 4) analysis. Because there is a lack of thread analyses of Twitter conversations and hence a rationale for studying such conversations, the choice of using qualitative analysis is justified. The approach taken is exploratory, and question generating rather than theory generating. One might argue that rationales from online forum analyses could be used, but Twitter is fundamentally different in its way of displaying conversations. The default view of a user's timeline, or the timeline of a hashtag, hides the conversation from the user. This entails that for many participants, the only view of the ongoing conversation might be just the tweet replied to (depending on device used by the participant). Some users would want to expand the conversation (the View more in conversation option) and see it as a whole before replying, but the tree structure would still not be visible.

The content analysis was performed in order to map the thematic contents of the threads and thereafter analysing the conversation dynamics, i.e., how the participants interacted with each other utilising both argumentative and emotional texts. As a first step, the thematic content of all tweets was identified and coded according to the steps outlined above. In the second step, the types of tweets and responses were coded to analyse how the participants talked to each other. Drawing on Zubiaga et al. (2015), three dimensions were used: type of message (e.g., assertion, question, opinion, facts), type of response in relation to replied-to tweet (e.g., answer, evasive answer, question, rhetorical question, requesting source, agreement, disagreement, topic change) and context (e.g., polarised branch, echo chamber branch). The approach was data driven rather than theory driven. Categories were added as they were discovered and each tweet was compared to previous categories (e.g., Corbin and Strauss, 2008; Glaser and Strauss, 1967). One code for each dimension was assigned to each categorised tweet. In the last step, in order to analyse the reaction to an invocation by a mention, all tweets including a mention of a previously not participating user in the thread were scrutinised. These were coded with the categories talk-about and invitation, accompanied by a note of whether the invocations were successful or not.

Larsson (2014) categorised participants into the following groups: Citizens, Media/PR, NGOs/Non-profits, Far left, Left, Right, Far Right and Pirate Party. A similar categorisation is made here, but user type is separated from political position. The following user types were identified among the active and passive participants in the conversations: Political actor (87 participants), Media/PR (64), Celebrity/Artist (8), Author (10), Citizen (834) and Others (8), including Member, Union and NGO/Non-profit. Three main political positions were identified among the active participants: Left (51), Right (163) and Far right (100). Citizen and Unknown were the default categories and participants were categorised into a group if their profiles clearly stated they belonged to the group. This paper takes the same viewpoint as Wilkinson and Thelwall (2011) in that public data can be collected without consent but anonymisation is necessary to ensure no potentially sensitive information is revealed. The categorisation was based on publicly available Twitter profile data. After the categorisation, all screen names (including mentions in tweets), names and user IDs were encrypted to make sure that all tweets were anonymised before the qualitative analysis. An update option was built into the tweet coding tool so that an uncategorised participant could be categorised into a political position, if the tweet content clearly stated this. Eight participants were categorised based on tweet content.

The analysis of the sparking of conversations focused on what type of user posted the initial tweet and the immediate reaction followed. The analysis of development and dynamics had its focus on the conversation patterns after the immediate reaction. In this phase I focused on the user types involved, the velocity of the conversation, the interaction among the participants and to what extent polarisation or echo chambers were visible. The analysis of the final phase closure focused on how the participants reached consensus, if they did, or otherwise how the threads ended.

Descriptive statistics over the activity is also provided. To see how different user groups behaved during the two weeks, the users were divided into three groups based on activity as by Bruns and Stieglitz (2013). Here, the most active 1% users form one group, the next 9% active form a second group, and the least active 90% form a third group. Activity is here defined as the number of tweets posted, regardless of tweet types.

Analysis

Overall life cycle

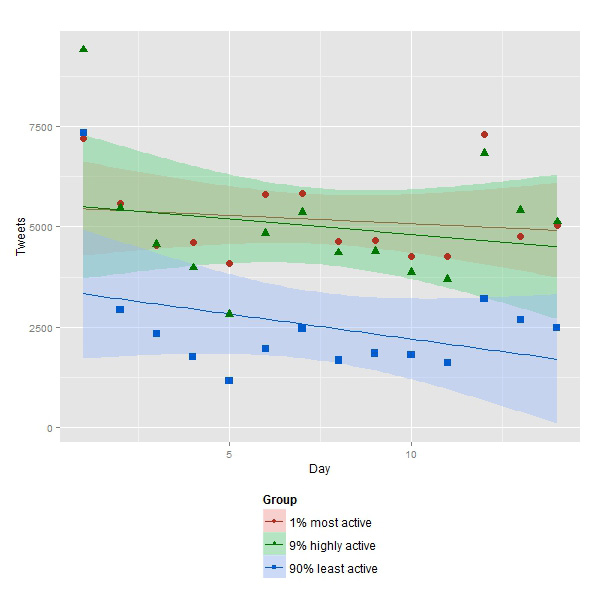

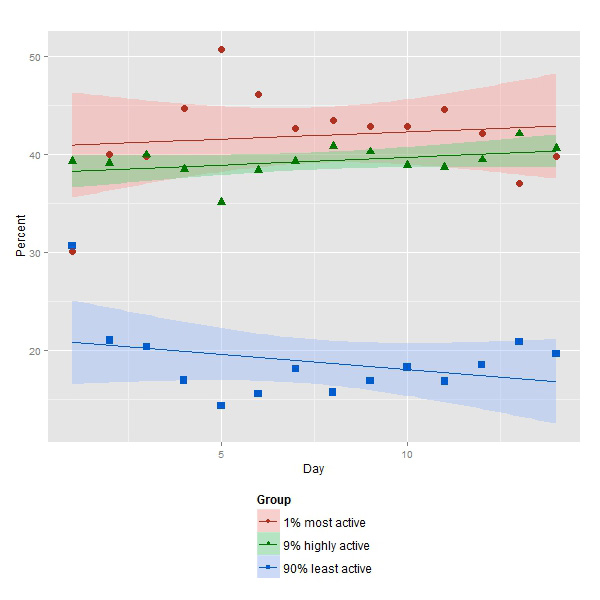

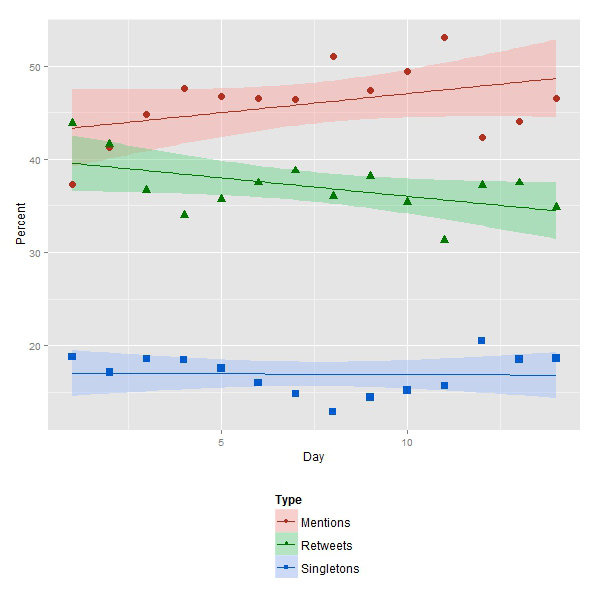

Over the course of the two weeks the attention of the participants shifted as a reaction to various events. The first few days were dominated by conversations about opinions of the agreement, and then the attention turned to migration politics and a couple of specific issues related to this topic. The new discussions that took place seem to be one kind of closure of previous discussions. Within controversy studies this kind of closure is dubbed 'abandonment' leading to a situation in which involved parties fail to reach some sort of agreement. Those interested in democracy discussions simply shifted to another topic. Activity was at its highest the first day after the press conference (Figure 1). Each series is represented by a dot for the actual count for a given day, a regression line and the area in which 95% of the observations are expected to be situated within. The level of engagement was symmetrical for the three groups; when overall activity was peaking, activity for all three groups was peaking as well. Looking at share of tweets posted for each day (Figure 2), the activity looks different with the most active group having the largest share of tweets when overall activity is low, most notably during day five. The least active 90% group were as most active during day one, accounting for 31% of all tweets, but after five days the group's share of tweets had decreased to 21%, and stabilising at 19% after ten days (Table 4). The share of mentions increased from day one with a dip between day eleven and twelve when Charlie Hebdo was attacked (Figure 3). The trends for singletons and retweets are similar; the shares of these increase and decrease simultaneously. Closer to an event, at least judging by the current case, activity appears more focused on informing and relaying information than posting tweets addressing other users. Similar findings have been made by Jungherr and Jürgens (2014) and Mascaro and Goggins (2015).

Figures 1-3 and Table 4 all show a clear pattern. The more distant the event was the more dominant was the top 1% active group and the larger was the share of conversational tweets. Closer to the event, the least active 90% group was at its most active. The middle group was different with a relative activity level staying pretty much the same throughout these two weeks.

| Top 1% | Highly active 9% | Least active 90% | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days | Accumulated tweets | Avg % | Accumulated tweets | Avg % | Accumulated tweets | Avg % | Total |

| 1 | 7,207 | 30 | 9,413 | 39 | 7,334 | 31 | 23,954 |

| 5 | 26,026 | 41 | 26,228 | 38 | 15,490 | 21 | 67,744 |

| 10 | 51,225 | 42 | 49,014 | 39 | 25,240 | 19 | 125,479 |

| 14 | 72,568 | 42 | 70,069 | 39 | 35,210 | 19 | 177,847 |

The December Agreement threads

Given the analysis above we now turn our attention to the ten threads sampled for content analysis. Table 5 displays some relevant descriptive statistics. Naturally, the most common theme concerned the agreement and questioning the agreement was far more common than expressing support. A common opinion was that the agreement in itself or its construction was undemocratic, a sentiment expressed and discussed in eight of the threads. Political actors were discussed to a larger extent, mainly in a negative way. Opinions of politicians betraying their constituents were common. Some participants expressed disappointment in the lack of appropriate alternatives to vote for, or threatening to vote for another party or not vote at all. Another theme focused on politicians not listening to public opinion. There were also discussions on how to interpret statistics as well as questioning sources used in discussion. As in the study by O'Connor and Rapchak (2012), the reliability of different sources were questioned, both those of alternative and mainstream sources. It was clear that participants chose what to believe in and what not to believe in.

A general theme was who might benefit from the agreement. The most often pronounced opinion was that the Sweden Democrats were the winners. The Sweden Democrats were discussed quite frequently in general; the most common theme here was whether the party could be seen as democratic. As Larsson (in press) found, there were several examples of its supporters questioning criticism towards the party. The presence of far right supporters is not surprising in this setting, having been found previously by both Larsson (2014) and Lorentzen (2014). In this special case it is even less surprising as the agreement did not include the Sweden Democrats.

| Thread | Volume | Participants | Start | End | Length | Velocity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 277 | 194 | 2014-12-27 12:37 | 2015-01-04 16:22 | 195.75 h | 1.42 |

| B | 74 | 53 | 2014-12-27 12:39 | 2014-12-30 22:09 | 81.5 h | 0.91 |

| C | 78 | 54 | 2014-12-27 13:21 | 2014-12-29 11:31 | 46.17 h | 1.69 |

| D | 29 | 19 | 2014-12-27 14:19 | 2014-12-27 18:53 | 4.57 h | 6.35 |

| E | 70 | 20 | 2014-12-27 14:46 | 2014-12-27 22:23 | 7.62 h | 9.19 |

| F | 79 | 29 | 2014-12-27 18:58 | 2015-01-01 23:09 | 124.19 h | 0.64 |

| G | 70 | 52 | 2014-12-27 19:42 | 2014-12-31 02:05 | 78.38 h | 0.89 |

| H | 126 | 18 | 2014-12-28 04:20 | 2014-12-29 19:32 | 39.2 h | 3.2 |

| I | 38 | 37 | 2014-12-29 21:22 | 2015-01-04 22:10 | 144.8 h | 0.26 |

| J | 314 | 19 | 2014-12-31 13:39 | 2015-01-01 16:51 | 27.21 h | 11.54 |

Next, attention is turned to conversation dynamics. The most frequent tweet types were assertions, questions, comments and declarations of opinions (Table 6). Common response types were statements, voicing disagreement, questions and voicing agreement (Table 7). Sarcasm or other attempts to be humoristic was not as present as in the study by Trilling (2015), but there were a number of examples of negative comments regarding politicians and other participants.

Slightly more than half of the questions were answered, most often with an answer such as assertions, comments, explanations and clarifications, but also with counter questions and evasive answers. Comments were also replied to at a similar rate. These were most often met with counter comments or questions, disagreement and agreement. Assertions and opinions were less frequently replied to. When an assertion was replied to, it was so most commonly with a counter assertion, an opinion (most often disagreement) or a question. Opinions were met with other opinions, agreements and in some cases disagreements.

A large share of the coded tweets was posted during the first 24 hours. On the first day, opinions were most common (137 tweets), followed by assertions (135), questions (121) and comments (99). There was a slight shift from day 2 and onwards, as assertions were most common (158), followed by comments (126) and questions (114). Opinions were less frequent (66). Among the responses during the first day, disagreement and declarative statements were dominant (126 and 127), followed by questions and answers (88 and 76). After the first 24 hours, statements became more common than disagreements (150 and 127), with questions and answers the third and fourth most common response types at 83 and 77. Thus, there is an interesting dynamic in the material as information types shifted slightly from day 1 and onwards, with more focus on expressing opinions and disagreement with other participants during the first day, and fewer opinion-related tweets during the following 13 days. This can be compared with an opposite pattern in Heverin and Zach's study (2012) in which information-related tweets dominated during the first few hours after an incident, while expressions of opinion became more prevalent over time.

| Type | n | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Assertion | 293 | |

| Comment | 225 | Including suggestions |

| Declaring opinion | 203 | |

| Explanation | 74 | Including clarification, informing |

| Facts | 22 | Including links to other source, quotes, potentially made up facts |

| Humour | 19 | Including sarcasm, irony |

| Insult | 29 | |

| Question | 235 | Including counter question, rhetorical question |

| Other | 21 |

| Response type | n | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Agreement | 110 | Including support, partial agreement |

| Answering question | 93 | Including assertions, comments, clarifications and explanations |

| Disagreement | 253 | Including questioning, counter arguments |

| Evasive answer of question | 33 | |

| Expressing disappointment | 32 | |

| Provocation | 10 | |

| Question | 160 | Including counter question, rhetorical question |

| Requesting answer | 41 | Including requesting clarification |

| Requesting source | 10 | |

| Statement | 314 | Including comments, suggestions (not inviting further discussion) |

| Topic change | 7 | |

| Other | 39 |

With the inclusion of 1,011 users it comes as no surprise that the vast majority were citizens. This group accounted for most of the tweets; 1,003 of the 1,155 tweets in the ten threads. Media/PR actors accounted for 54 tweets and authors for 35. With 87 political actors involved in the conversations, their total number of tweets at 40 might be disappointing from a citizen point of view, but perhaps not unexpected. The most common interaction was between citizens. Their interactions consisted mainly of assertions, comments, questions and opinions as tweet types and the response types statements, answers of questions, disagreement and agreement. Citizens sent 321 tweets to politicians. Most of these tweets were opinions, assertions and questions, but few of these were replied to. As responses to politicians' tweets, citizens expressed disagreement almost three times more often than agreement. They also expressed disappointment and responded to tweets with questions. Political actors on the other hand responded with only 35 tweets to citizens, including answers, questions, agreement, questioning and statements. It should be said though that not all of the tweets sent by the citizens appeared to be openings for conversation, rather communication took the form of venting disappointment, disagreement and posing rhetorical questions. Similar to the debate study by Mascaro and Goggins (2015), far from all replies invited further conversation.

Other groups, including political actors, tweeted to politicians infrequently (32 tweets in total). Overall, political actors were given much attention. 31% of all tweets in these ten threads were sent to a political actor. This is in line with the findings of Larsson and Moe (2013); elite users are given attention whilst activity is dominated by non-elite users. The interaction between citizens and politicians were largely one way.

Considering political positions, 312 tweets could be traced to the far-right camp, 123 to supporters or politicians of the Alliance parties and 109 to the left side supporters/politicians. Thus, the challengers to the establishment were represented by a fairly large and vocal group. There were few examples of cross-boundary agreement and support. Far right participants expressed agreement with right participants five times and twice with left participants. The most frequent exchanges were between far right and left. Far right participants were addressed 71 times by left participants with 89 tweets going the opposite way. The most common interaction between these two groups were expressing disagreement, asking questions and requesting answers.

Far right participants addressed right participants 50 times, including 13 instances of disagreement, with right participants addressing far right dittos only five times. Right participants talked mainly to each other. Curiously, most often they disagreed with their own regarding the agreement, and they expressed disappointment. However, there were also instances of agreement and support.

Thread life cycle

This section outlines the life cycles of the ten threads by looking at the start-tweets and the initial reactions to these, how the conversations evolved after this initial state and how they were closed. Threads A, G and I were started by politicians. As the start-tweet of A was posted first of these, it is not surprising that this tweet was the most replied to. 152 replies were posted in a short period of time. Ten of these were replied to, and one reply in particular was made by the thread starter following which the thread sparked again. The start-tweets in G and I gave 45 and 35 replies respectively, but discussions did not take off following this. In a couple of cases, threads were started by a mass media or public relations actor. Thread B included mostly replies to the start-tweet but with no discussion. In thread C, two replies to the start-tweet sparked reactions. Thread D started with a link to a statement, and the only reaction to this was replies pointing out an error in the statement. Finally, three threads were initiated by citizens. One branch emerged in thread E, in which the start-tweet was replied to 15 times. Both H and J started with few replies to the initial tweet, but then major branches grew. In J, one of these was split into sub-conversations.

All of the threads were developed and ended over a short time span, from a couple of hours to a few days. The two largest threads in terms of number of tweets, A and J, were very different in their development and participation. The first of these was not conversational in the sense that longer chains of replying tweets were created. Rather, it consisted mainly of criticism towards the agreement and the Moderate Party. Most striking were the expressions of disappointment and disagreeing with the thread starter, with a number of instances of threats to vote for other parties, but there were also examples of agreement and support. The thread was unique in this set in the way it was started by a politician and then reignited when the politician replied to a question. Most of the tweets were posted in a short time span making it difficult to take part in the discussions. Citizens brought their opinions and questions to the light, but most of these were unanswered. Those tweets defending the agreement were not replied to, but criticism was met with agreement of the criticism. Contrary to A, the second large thread (J) included longer chains of replies but mainly consisted of mudslinging. Both sides of the discussion attempted to show that the other side was wrong. One branch was divided into sub-conversations of which two were echo chambers where like-minded agreed with each other. Opponents were mentioned but only participated with a few tweets. Assertions, comments, questions and opinions were met with statements, counter questions, disagreement, counter arguments and agreements.

Most of the analysed threads were shallow with little conversation. Threads B, I and F were such threads, dominated by participants from one major camp who mainly agreed with each other. A branch in F comprised a polarised discussion about religion, showing that a conversation thread can evolve in different and separate directions. Threads D and E did not spark substantive discussions. In the first case, a need for clarifying was the most significant part of a thread. In the latter case a sub-conversation was triggered by a provocation towards the Sweden Democrats. Similarly, thread G did not take off, but the thread starter was questioned and then made a clarification of what the tweet was supposed to express. Another thread that did not evolve much after the start was thread C. The start tweet was questioned in part by most participants. Most tweets expressed that the people were dissatisfied whereas the start tweet was about the parties, something that was pointed out by a few participants.

As noted at the outset of this paper, debates can end by resolution (agreement), closure (lack of agreement) and abandonment. In the current study, the large number of statements, here representing a large number of tweets not inviting further discussion, indicated participants wanting to close the discussion rather than proceed with it. The most notable example is thread A, in which opinions were posted with few attempts to engage in conversations. Another example is H, which involved participants from the whole political spectrum and was dominated by a few participants. In this thread, it seemed as the participants were consciously talking past each other without having any interest in either understanding or convincing. The thread mainly consisted of comments, questions, pieces of facts, questioning and requesting answers.

As a consequence of this behaviour, consensus formation was rare in the studied threads, but it did happen in a small branch in thread B where two participants discussed. In C there was consensus about a political researcher being wrong when claiming that the Sweden Democrats was the only party being disappointed with the agreement. There was also consensus about the agreement being hard to understand, but in this thread there were also examples of consensus not being reached. In J there was a consensus about the December Agreement not being sustainable. Overall, the issue on which there was largest consensus was the agreement itself and the most pronounced sentiment was disappointment, which was not restricted to one political camp but all. Closure by abandonment was more common, happening in threads B, F, H and J. In thread F there was one instance of the thread starter blocking the opposing participant. Thread B was ended by the thread starter claiming the discussion was pointless, following several rounds of disagreeing with another participant.

Participation by invitation

Overall invitation statistics for the December Agreement threads are presented in tables 8 and 9. Politicians not previously participating in the thread were invited to 33 of the threads. The figures for the other major groups Media/PR and Citizens were 24 and 44 (Table 8). Many invitations were left unanswered, regardless of user category. Table 9 shows the number of successful invitations by user category counting only invitations to users not already participating.

| User type | Number of threads |

|---|---|

| Political | 33 |

| Media/PR | 24 |

| Citizen | 44 |

| Other | 8 |

| User type | Successful | Total | Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Political | 7 | 72 | 0.097 |

| Media/PR | 3 | 40 | 0.075 |

| Citizen | 15 | 127 | 0.118 |

| Other | 1 | 8 | 0.125 |

In the ten sampled threads, invitations were sent 217 times to 50 different users previously not participating in the thread invited to (a few of these were invited to more than one thread). Four of these participated following the invitation, one of them a politician asking to be untagged. The other three were identified as citizens. None of the invitations could be seen as a direct question to the invited user. Most of them were rather notifications of the ongoing conversation, sent to citizens as well as politicians, journalists and celebrities. Talk-about mentions was less common with the corresponding figures being 18 and six (one was talked about in four threads), and none of them participating. All talk-about mentions but one were substitutes for names of politicians, parties or party constellations (one of these a parody account). The other was an author/journalist talked about in a negative way.

Few users respond to an invitation. It is expected that a user do not respond when being talked about, but in these threads such mentions were exceptions. In thread A, there were clear examples of invitations to politicians who did not answer the call. It seems as if participants to some extent were talking to someone not answering, and possibly not listening, and therefore the controversy did not develop. The arguments were brought forward as in an echo chamber but to an audience that is quite diverse.

Conclusions

The focus of this paper has been on tweets that can be considered as conversational through the reply function. Despite this material concerning a dramatic event involving core aspects of a well-functioning deliberative democracy, few examples of democratic debate were found. If such an event does not lead to democratic debates, will any at all be found on Twitter? Building on results of the present study, Twitter seems to be an arena where opinions are not changed. Seemingly, participants enter with an aim to act within an echo chamber and therefore there is really no intention of renegotiating political positions. This can be contrasted to Weinberger's (2007) argument relating to Wikipedia entries, stating that the authors of the texts, striving for a neutral point of view in the end reach some kind of consensus. The results of the current study indicate that many participants opened up for discussions but all too often a substantial interaction failed to materialise. As there were examples of threads with many tweets and many participants, it can be said that Twitter indeed facilitates discussions. However, problems regarding the restricted character of the user interface exist, seemingly creating obstacles for engagement on controversial topics.

While public discussions take place on Twitter, due to the restrictions of the platform they are not visible to everyone. The disconnected user (followership-wise) is restricted to following hashtags. To be able to track threaded conversations, the user must follow the involved participants or at least two of them and then expand the conversation by clicking on a conversational tweet. Longer conversations can then be opened by clicking on View more in conversation. This means that conversations are more likely to evolve within seemingly walled gardens of echo chambers, i.e., tightly knit groups, followership-wise. But if Twitter altered its code so that the reader could see all these directed tweets by just following one of the users it would be difficult to keep track of conversations; the timeline would be flooded with tweets. And the conversations are, seemingly, already inclusive of participants who cannot agree due to their ideological positions. There are plenty of expressed emotions in these open discussions, and these often escalate and reinforce each other. One might suggest it would be better to retreat to echo chambers to be able to have reasonable conversations, but this would make it harder to be exposed to opposing opinions. However, such opinions can be brought into the discussion by linking to any resource.

If we contrast the findings with the categories focused on by Burnett and Buerkle (2004), we can start off with discussing the concept of community. At the hashtag level, the community is likely to be loosely knit. When someone replies to a hashtag, an ad-hoc community is created. This community is by default including only the interacting participants and their joint followers, thus being a small, tight and dense community, but the community can be widened through the inclusion of a dot character in front of the @ (widening to all of the tweeter's followers) or including a hashtag (widening to all followers of the hashtag). However, only a small share of the conversational tweets included a hashtag. Looking at the category hostile interactive behaviour there were a few examples of threads or parts of threads where hostile language or behaviour is present. In some threads there was not even an attempt to understand or convince non-like-minded. Collaborative non-informational interactive behaviour in the form of small-talk exists within echo chambers. If we view collaborative informational behaviour as more substantive political talk then there are examples of this too, but arguably less than what would be expected in a traditional discussion forum. But there is no community-oriented approach to the conversations as the community is fluid.

The level of disagreement might be attributed to the controversy, as Savolainen's (2015) study on an arguably controversial topic showed similar tendencies. However, some attribution must be given to the communication model as well. If conversations are more likely to grow in a tight followership network, then such a network must containe diverse opinions for disagreement to be this present. The only followership graph of the Swedish political Twittersphere has been given by Lorentzen (2014), who included the most prominent users of the hashtag #svpol. While showing polarisation, it also included quite a few connections between the three main clusters. Lorentzen (2014) also found that the most active Twitter users also were more conversational. With the present study having its focus on conversation, it is reasonable that a similar followership graph is underlying here. In a context where like-minded are followership-wise disconnected from non like-minded, participants are probably more likely to agree rather than disagree.

This case is indeed quite unique, but the presence of conversation beyond the hashtag opens up for future research. Are conversations like these common within other topics as well? Are conversations common outside of sudden events like the December Agreement? Another relevant issue that was not investigated here is if replies differ between different types of devices used by the authors of replies. In one type of device the whole conversation might be displayed for the user, while in another type of device only the tweet the user is replying to might be visible. This entails that one reply could be given in relation to the whole conversation, but another reply in relation to only one tweet. With the API giving information about what kind of device is used (the source metadata field), such an analysis is possible.

Information sharing and information diffusion, as seen in the articles cited above (Dyagilev and Yom-Tov, 2014; Heverin and Zach, 2012; Small, 2011; Sutton et al., 2014; Tinati et al., 2014), are important aspects of Twitter usage, but they are only parts of the informational activities on the platform. With the data collection method used, conversations and discussions can be extracted. Information sharing is present in the conversations, but is not a dominant activity in the conversation threads. They are more about expressing opinions, asking questions, replying to questions, commenting, asserting and complaining. The analysis gives us insights into how Twitter conversations are initiated, evolve, and end, as well as how people interact. As opinion polls gives us indications of what people in general think about political issues as well as indications of trends, an analysis such as the one here gives us insights into the why.

Some valuable insights arrive with the present study. First, there are conversations beyond the hashtag, and many of the tweets in the follow-on conversation express opinions that might be valuable for politicians to be aware of. Secondly, many conversations are very rapid and difficult to participate in for those politicians that receive many tweets in a short time space, as seen in thread A. The data collection method used here shows that it is possible to collect conversation threads, and keeping track of when such a conversation flares up in real-time is also possible. Even though participating in the conversations might be difficult, being aware of the conversations is not. For political actors, Twitter might be another source to gain insights into what some of their voters want, and how they react to different decisions, or statements, rather than a forum for discussing with them. Thirdly, different opinions do meet in this medium but there are few signs of participants from different political camps being interested in arriving at consensus. There were a number of examples of participants trying to point out flaws in the opponent's arguments, but hardly any instances of attempts at convincing opponents to change their viewpoints.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the anonymous referees whose comments and suggestions have helped improving the quality of this article.

About the author

David Gunnarsson Lorentzen is a PhD Student at the Swedish School of Library and Information Science, University of Borås, SE-501 90 Borås, Sweden. His main research interests concerns social media studies with a focus on method development. He received his Master's degree in Library and Information Science from University of Borås. He can be contacted at: david.gunnarsson_lorentzen@hb.se.