Vol. 11 No. 2, January 2007

| Vol. 11 No. 2, January 2007 | ||||

Despite the importance of the subject of personal informaton organization behaviour, only a small number of user studies have been published concerning how people organize paper files in their offices (Kwasnik 1989 & 1991), e-mails (Ducheneaut & Bellotti 2001; Whittaker & Sidner 1996), bookmarks of Web pages (Boardman & Sasse 2004), and objects on the computer desktop screen (Barreau & Nardi 1995; Ravasio et al. 2004). One reason lies in the difficulty of gaining access to people's personal hard drives, which provides the principal record of such behaviour. The approach we use to collect data is through a series of student group projects, where each student obtains permission from three or four friends to harvest the filenames, folder names and file structure from the personal computer or notebook that they use at work. These students have to complete either a small Master's thesis or a group project (plus an extra course) to complete the requirements for the M.Sc. (Information Studies) programme at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. We endeavour to have a group of students every semester carry out data collection and analysis, and hope to obtain useful results after a few rounds of data collection. We have carried out two rounds of data collection in this way.

The research questions that the project seeks to address fall into three areas:

The results of this project will shed light on an important type of human categorization behaviour, engaged in by most knowledge workers and white collar workers today. The results will also have implications for the design of file structures in operating systems, for designing personal information systems, for designing personal work spaces and personalization features in enterprise portals and organizational digital repositories. Further research in the future will build on this base to relate folder organization and naming conventions to particular groups of people and the occupational roles they engage in.

Conducting such research becomes all the more important as information seeking activities increasingly involve the use of documents created and distributed in digital form. Electronic file organization will affect how well and in what ways people locate and retrieve documents in the course of their work with resulting impacts on work productivity and effectiveness. Furthermore, we expect that more and more organizations will impose organization-wide file structures, and require employees to store files on networked file servers, in an attempt to retain organizational memory and develop knowledge repositories, making knowledge of electronic filing behaviour even more important for the creation of efficient and participant-friendly information systems.

Files and folders have of course, their non-digital counterparts and the study of how these are classified and arranged was the subject of early investigation. Using interviews and guided office tours, Malone (1983) observed two kinds of desk organization, neat and messy. In his study he noted that, although not statistically generalizable, there was evidence that messy desks created retrieval problems for their owners. Malone speculated that the kind of organization chosen would often depend on occupational role. He also observed two elementary units of document organization: files (explicitly titled and arranged), and piles (not titled and not ordered in any logical way). The files, he noted, gave many people difficulty as they had a hard time deciding on a classification scheme. He also observed that files and piles, have two functions: finding and reminding. Malone urged the designers of computer environments to take into account this later function as it was at the time of his writing completely overlooked.

Kwasnik (1989) also focused on physical desktops and relied on guided office tours for her study of how people organized their offices. However, supplementing these tours she had participants sort a day's mail using the thinking-out-loud method. Kwasnik's assumption was that the choices people made about classification depended on their situation. Classification was 'person- and situation- centered... not object centered' (Kwasnik 1989). Her results suggested that people organize across seven dimensions: situation attributes (source, use, circumstance, and access); document attributes (author, topic, and form); disposition (discard, keep, postpone); Order/Scheme (group, separate, arrange); Time (continuation, duration, currency), value (importance, interest, confidentiality); and Cognitive State (don't know, want to remember). However, of these dimensions, situation attributes, especially use, appeared to be the most common.

In a 1995 article, Barreau and Nardi compared the results of their separate investigations into the electronic filing habits of primarily inexperienced DOS users and experienced Mac users. They found striking similarities between the two groups. Rather than use built-in search features, what Barreau and Nardi referred to as logical searching, people tended to prefer location-based searching, that is, a process where the user guesses which folder a file is in, browses its content and, if the file is not found, repeats the process. Barreau speculated that this was so 'because it more actively engages the mind and body and imparts a greater sense of control' (Barreau and Nardi 1995: 40). For the Mac users, Nardi suggested that location searching was preferred because of the 'difficulty in remembering the name of the desired file' (Barreau and Nardi 1995: 40). Both authors noted that each group gave much thought to naming their files in an effort to make them easy to spot when browsing, but spent little time maintaining their file collection. Barreau and Nardi made two other observations. The first was that electronic file placement served not only a retrieval function, but also acted as reminders for people to take action later. In this respect, the electronic environment was an extension of the physical desk. The authors speculated that this function enhanced the desirability of location-based searching as people would encounter their files more regularly. Their second observation was that files could be divided into three categories: ephemeral (short life span), working (life span measured in weeks or months, frequently used in current work), archived (life span measured in months or years, infrequently accessed). In regard to this categorization, Barreau and Nardi noted that although people did not archive very much, that class of information received the most attention from computer designers, whereas ephemeral information was neglected, even though it made up a significant number of files.

Given the great importance of e-mail, it is not surprising that it should receive attention in the literature exploring the filing habits of users. Whittaker and Sidner (1996), noted that e-mail was now used for a variety of functions, for which it was not originally intended and that this produced what they called e-mail overload with the inbox acting as a task manager. In their study they found that the volume of e-mail received and the unintended task manager function made the process of filing either difficult or unrewarding for users. They identified three principal ways in which people handled e-mail overload depending on whether they use folders and whether they clean their inboxes daily. The first group are the no-filers. These people do not use folders, rely on periodic purges to clean their inboxes, and use the search facilities provided by the software to find relevant files. No-filers have trouble using the inbox as a task manager as a result. In contrast to the no-filers, frequent filers have relatively small inboxes and use lots of folders. As a result the inbox can function successfully in its second role of task manager. However, there are high maintenance costs involved which means that this strategy is best for those people who can check their mail daily and who receive relatively little mail to begin with. Finally, there are the spring-cleaners. These people engage in a strategy of intermittent cleanup, use lots of folders, and have large inboxes. There is not as much maintenance involved here and items are discovered before deadlines. In general, people using this strategy tend to receive fewer messages and have more time to handle them.

Balter also looked at the problem of e-mail filing, but from the point of view of designing a mathematical model that could predict the most efficient method of storage and retrieval. The model took into account keystrokes, pointing and mental preparation times. Balter concluded that 'the best long term strategy is to use folders sparsely in combination with the search functionality' (Balter 2000: 111). The model also suggested that it is more efficient to have between four and twenty folders for manual searching, that more than thirty folders is not an efficient strategy, and that it is inefficient to conduct cleanups of the inbox as the 'gain in time a reduced number of stored messages gives is less than a few minutes a day' (Balter 2000: 112).

In their study of the folder organization and file retrieval of sixty e-mail users, Ducheneaut and Bellotti (2001) found a great range in filing structure (from one inbox to 400 folders) and that the complexity appeared to reflect the e-mail experience of the individual user. The folders people used tended to fall into the following categories: sender, organization, project, and personal interests. In many cases the categorical paradigm chosen appeared to reflect the nature of the wider organization of which the user was a part (projects for example in research institutions as opposed to departments in well-established business firms). They also found that because people wanted immediate access to information, the folder hierarchies were generally shallow, typically having only two levels. Ducheneaut and Bellotti went on to challenge some aspects of Balter's model of efficient e-mail management, noting that people tend to have numbers of redundant or no longer used folders that add significant numbers to the total count. In Balter's model these redundant folders are not accounted for and so a recommendation for a smaller number of folders is made. The authors also noted a number of design features that hampered users' freedom to chose how to manage their e-mail. Among these was the convention of listing folders alphabetically, whereas users wanted to organize by priority or frequency of use. Similarly, they noted that users' felt that search features were too slow to set up and therefore of limited attractiveness as compared to sorting and manually browsing files.

More recent work by Boardman and Sasse (2004) examined user practices surrounding personal information management (PIM) for three common tool types: documents, e-mail, and Web bookmarks. In terms of organization, they devised a typology of three file management strategies: total filers (filing was done at the time of document creation), extensive filers (while filing was frequently done at the time of creation, many files remained unfiled until after task completion or during a spring cleanup), and occasional filers (for whom filing was not a priority). This typology was only partially transferable to the case of e-mail for which they found only a few no-filers (no folders, periodic spring-cleaning of the inbox) and some frequent filers (filing done immediately, no spring-cleaning). Most people appeared to employ multiple strategies. The authors divided these users into two groups based on how much filing they did on a daily basis. Bookmarks also required a different typology. A significant number of no-filers were found, but the rest used multiple strategies which were divided by the authors into two groups depending on how often they filed bookmarks upon creation. Boardman and Sasse also examined the names people assigned to folders. For files, these names were derived from a number of common types: projects, document classes, and roles. For e-mail folders, a couple more categories had to be added to this list; namely, contact, topic/interest, and mailing list. Bookmarks relied on topic/interest, document class, projects, and contacts for their categories. Boardman and Sasse's users did not bother with much spring-cleaning of files and folders. Most of the spring-cleaning that was found occurred at times of 'major life events' such as changing jobs. However, like many previous studies, the authors found that users preferred browsing as a search strategy for all three tool types. However, as well as location browsing they relied on the sorting features of their software to help them find what they were looking for. In general, participants were confident they could find the things they needed. Boardman and Sasse raise a number of relevant issues in their discussion. They claim that the use of multiple strategies by many users suggests that previous studies exaggerated the differences between people. Instead they feel that differences are to be found across differing tool types and according to the individual's perception of the value of the information. They also suggest that the tendency to organize may depend on personality type with tidy people tending to organize more than others. A final point raised in their discussion is that archives, in contrast to Barreau and Nardi, were seen as valuable even if infrequently used. In order to deal with these issues, Boardman and Sasse propose two new concepts: information usefulness (active, inactive, dormant, and unassessed); and information ownership (mine, and not-mine).

Ravasio et al. (2004) examined the classification and retrieval of e-mail, bookmarks and other documents for a group of sixteen participants. In terms of classification they discovered that archiving was 'a decidedly important matter' as such items were used in the course of people's work. As a result much work was done in creating file structures that would reveal content meaning. This work was seen as an on-going and difficult process. In contrast to archiving functions, temporary storage was provided by the desktop (but only by the experienced; inexperienced users did not realize it was possible to store their files on the desktop). As the desktop filled up with files, people tended to separate them into three groups: those immediately useful (kept in place), valuable things (archived), and the rest (deleted). Ravasio et al., in common with most other researchers, found that people were reluctant to use search tools; only the highly skilled did so at all and only as a last resort. Most believed themselves capable of remembering where the files had been stored. To this effect, they used spatial location as a means to jog their memory. But unlike Barreau and Nardi, the authors here argue that the main reason for people not using the search tools is the complexity of the design and the fact that the 'technical document metadata' wasn't useful because it did not reflect how people thought about their files.

Twelve professionals participated in the study—four from each of the following industries: auditing, logistics and education. All the subjects used PCs and a Microsoft Windows operating system (none was a Macintosh or Unix/Linux user).

The data were collected from the subjects in three phases. First, a structured questionnaire was sent to the subjects to collect basic information on their personal background, work experience, and the characteristics of their workstation (including the location of their main document collection).

The researchers then arranged an appointment with the subject to scan the subject's hard disk and take a screen shot of the desktop. A computer program called STG FolderPrint Plus was installed on the subject's workstation (to be removed at the end of the session). This program was used to capture data such as the tree structure of the nominated drive, levels of folders, and date on which folders and files were last modified. The software was selected for its low cost and its capability to export the data captured in various formats including Microsoft Excel worksheet and HTML. If the computer system did not allow software to be installed, then the DOS command “dir/s/tw” was issued at the command prompt to list files and folders on the hard disk, and output to a text file. A screen shot of the subject's computer desktop was taken to understand how the subject arranged files and folders on the desktop.

After the hard disk scanning, a semi-structured interview was carried out. The subject was asked open-ended questions about their strategies in naming and organizing files and folders, and in locating and retrieving files. The subject was asked to think-out-loud on how and where he would save a hypothetical work document, as well as how he would retrieve an old file (identified by the interviewer after scanning the hard disk).

The subjects usually stored their folders and files on their desktop and/or the main hard drive of their computer—either C drive (C:\) or D drive (D:\). Eight subjects had their main folders in their C:\Documents and Settings\<username>\My Documents folder—the default document folder created by the Microsoft Windows system. Others stored their folders in the root of their C or D drive.

Seven of the twelve subjects indicated that they stored documents on the desktop. The majority of the users did not arrange the files on the desktop in any particular way. However, one subject made an effort to position his documents and place current files in the centre of the screen. Another subject arranged the files from left to right so that it would be easier for the eye to track the documents on the desktop, which could get quite cluttered during the busy periods of his working schedule.

Ravasio et al. (2004) noted that users tend to regard the desktop screen as a temporary storage area. Barreau & Nardi (1995) also found that files on the desktop were ephemeral (such as to-do items). Similarly in this study, seven out of twelve participants used the desktop to store files and folders related to their most current projects or tasks. Users would merge the files and folders on the desktop with their main document collections upon completion of the related work. One user said he saved his documents on the desktop so he could delete them easily later.

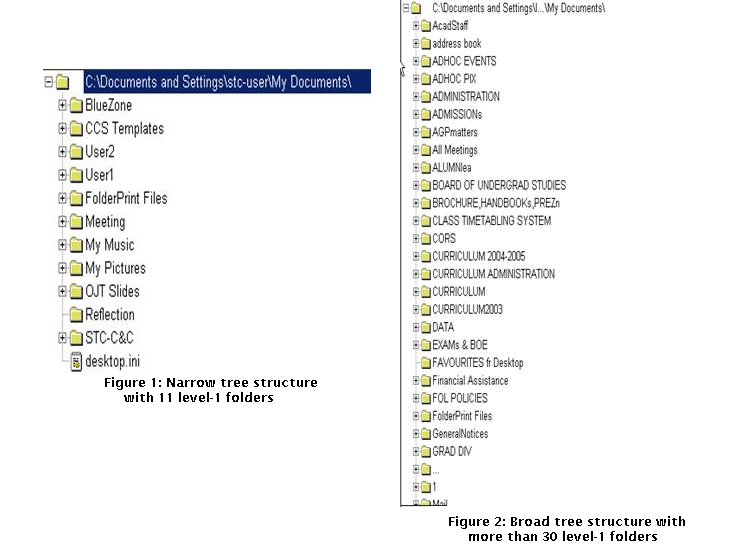

Files on the hard disk are organized into folders and sub-folders. The folders and their sub-folders form a tree structure. The tree structure can have different shapes and characteristics. The tree can be broad and shallow, with many first level folders but few levels overall. Or it can be narrow and deep, with few first level folders but many levels.

Five of the twelve subjects had fewer than ten first level folders. Other subjects had more than nineteen first level folders. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate a narrow and a broad tree structure. The average number of first level folders for all the users was nineteen!

One user had sixty-four first level folders that go a maximum of three levels deep. On the other extreme, one subject had just nine first level folders but a hierarchy that reached a maximum of eight levels. Six users had tree structures that were at least two levels deep, while four users had tree structures that went at least three levels down.

The subject with a broad and shallow tree structure created his folders based on specific work assignments or areas. Other users had more broadly defined first level folders, such as 'Work', within which they created subfolders for specific projects. Subjects with a deep file structure tend to have some kind of systematic classification system, which sometimes included temporally labelled folders (e.g.,Work\Exampapers\03041\NBS\UG\AB10103041.pdf). On the other, subjects with many files in one folder tended to express their classification in the filenames, which may contain two or more attributes. This is explained in the next section.

A majority of users (ten out of twelve) would only create folders if there were at least one file to place inside. But two users would create folders with no files in them, usually in anticipation of the work required for their forthcoming projects.

The file folder names of the respondents were classified into the following categories: organizational function or structure, document type, project or client name, priority ranking, long-term storage, miscellaneous or temporary, subject or topic, and task or area of responsibility. The list of folder categories with examples is given in the Appendix. It was found that document type was the most common category of folder name with each participant having at least one folder of this type. Examples of this category are: Articles, PPT (Powerpoint), and LOA (Letters of Authorization).

The second most frequently occurring category was organizational function or structure. Organizational function folders such as Finance or WITS (Work Improvement Teams) were present in the majority of participants' hard drives. They did not appear, however, on the hard drives of the academics in the sample, suggesting that occupation may have an effect on folder naming strategies.

Not surprisingly, the miscellaneous or temporary classification, was the third most frequently occurring category. Examples of this category of folders include the most obvious label, Miscellaneous, but also others such as General or Overall. More interesting was the fact that only one of the participants whose job was in the logistics industry had folder names in this category, again suggesting that occupation may have an effect on naming and filing conventions in this case.

The users were queried on when they would organize their files. Five of the twelve subjects indicated that they would do so when they were creating or saving the files (frequent filers), while three stated that they would only do so when they have the time (spring cleaners). The rest of the users indicated that they would do so when they could not find a document, or when the user's personal computer performance started to slow down due to lack of storage space. One subject said that with an external hard disk, he no longer needed to organize his files, since his back up would be in the external hard disk.

The thinking-out-loud exercise provided additional insights on the filing behaviour and reasons for the behaviour. Nine of the twelve users would file a newly created document in a folder, while two would save to the desktop screen, and one would place it on his D:\ drive (unless he could remember which folder was relevant). Six of the nine users who filed in a folder chose the most appropriate folder for the document at this time, based on the task or topic associated with the document. The rest would put the document in a catch-all folder. All the nine users would create the document first, and then choose a folder or destination. Contrary to this, one user said he would first create an appropriate folder for the impending document.

Seven of the twelve subjects stored documents on their desktop. One user regularly cleaned up clutter on the desktop every Saturday. Another user would only clean up his desktop when 'something went wrong' with his system and the technician recommended that the desktop had to be weeded. The rest of the users would tidy up their desktop when the work or project related to the documents had been completed, or they judged that the documents were no longer needed or relevant. This could be weekly, half-yearly or 'whenever possible'.

Through the course of use, document collections accumulate duplicate folders, folders that fail to reflect current job duties, files no longer relevant, and so on. All but two subjects said they would periodically go through their document collections to tidy up files and folders, deleting files no longer needed and adjusting the folder structure. Of the two exceptions, one subject said his work was such that old files would be needed for reference in the future. The other subject did not see the need to tidy up his collection: his maintenance consisted mainly of backing up the entire collection.

Though a few users said they would carry out this task weekly or monthly, the majority would only clean up their files and folders 'as and when' or when they had time. One of the regular 'cleaners' reported feeling happy after a cleanup exercise because it would make files easier to find in future. Another felt good that the files would be 'more organized'. Two subjects felt a sense of accomplishment upon completing the task, three users viewed it as a tedious but necessary chore, and one considered it a waste of time as he 'had better things to do'.

Users can locate files in their personal document collection either by browsing the file structure or by searching the filenames or file content. Ten of the twelve subjects used primarily the browsing approach, and two would start with filename and keyword searching.

The browsers would generally pick the most relevant folder (by subject, project or task) at the first level, and scan the subfolders and files within. Two subjects had multiple drives and would have to ascertain the correct drive first. One subject would first scan the desktop screen in case the document was recent and he had stored it there. Another subject took into account the temporal attributes of the target file because his main folders were organized by how recent the documents were. When browsing did not work, the subjects resorted to the Search function in the Windows system. There were two exceptions. One user did not know the Search function existed. Another user knew about the Search function but preferred 'to retrieve by memory'.

It is not known whether the subjects had a rough idea where in the tree structure the file was likely to be located before beginning to browse, or whether they selected the categories level-by-level as they browsed the folder structure

Two subjects used primarily the Search function to locate files, although it is not known whether they searched by filename or perform keyword search in the file content. One subject said he had too many files and would not remember where exactly he had placed a file (especially old files). But if he failed to locate a file by searching, he would 'plough through' his entire collection.

We have carried out a small preliminary study of how twelve subjects managed and organized their electronic files on their computer hard disk at their workplace. The results are generally consistent with the results of previous studies of how people manage and organize paper files in their office, e-mails and bookmarks.

The majority of the subjects stored files on both their desktop as well as in a folder on their hard drive. The desktop tended to be used for ephemeral or temporary files as well as for working files used in current projects. The computer desktop appeared to serve the function of Malone's (1983) piles, reminding the user of tasks to be completed or needing attention. It also helps users to locate working files quickly. Some subjects positioned their files on the desktop spatially (e.g., working documents in the centre of the screen) or chronologically, presumably to be more effective in reminding them of tasks to be completed or help them locate working documents quickly.

The hard disk folders are used to store and organize working files and archived files. Some users may have a catch-all folder that serves as a pile of documents to be sorted or attended to later. Users may also have an external hard disk or networked file server for archiving or backing up files.

The subjects organized their folders and sub-folders in a variety of tree structures, from broad and shallow hierarchies to narrow and deep hierarchies. Most subjects had one to three levels of folders, with one extreme case with eight levels.

Consistent with Kwasnik's (1989) finding for paper files, we found that the labels for first level folders tended to be task-based or project-based, corresponding to Kwasnik's use dimension. However, our data also suggests that users employing a shallow folder structure tend to created task-based or project-based folders at the first level, whereas users with a deep folder structure tend to use broader and more generic folder names at the first level. The folder labels used with deep file structures tend to reflect some kind of systematic classification system. On the other, subjects with many files in one folder tend to express their classification in the filenames, which may contain two or more attributes.

Most of the subjects in the study were frequent filers who stored documents into appropriate folders immediately, or spring cleaners who clean up and file documents into folders periodically. As with the subjects in Barreau and Nardi's (1995) study, most of the subjects in this study preferred to locate files by browsing or navigating the folder structure, and only resort to searching when they failed to locate the file by browsing.

Folder naming conventions were investigated and classified into a number of categories. Of these the most common categories were document type, organizational function or structure, and miscellaneous or temporary. The last two categories appear related to occupation, as organizational function folders were not found on the hard drives of the academic participants, and miscellaneous folders were not found on the hard drives of most of those participants in the logistics industry.

We are continuing with the project using the same method described in the introduction and hope to obtain in this way a more representative sample from which significant conclusions can be drawn in regards to the relationship between folder structure and naming conventions, occupational roles, and accompanying information seeking behaviour.

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

© the authors, 2006. Last updated: 9 December, 2006 |