BOOK AND SOFTWARE REVIEWS

Gazzard, Alison. Now the chips are down. The BBC micro. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016. xii, 206 p. ISBN 978-0-262-03403-6. £26.95.

In her acknowledgements, Alizon Gazzard notes that the BBC Micro was her first personal computer and that it now has a place in her living room: the BBC Micro was also my first personal computer, and I still have it, but it is in the attic, not the living room! I continue to think that the BBC Micro was a brilliant little machine and that its operating system was superior to pretty well anything else available at the time. It became popular as a computer for schools, and I recall visiting a library in Moscow, probably the main social sciences library, where a computer laboratory was equipped with about a dozen BBC Micros.

The BBC Micro came into being as a result of a decision by the British Broadcasting Company to enter the field of what would now be called 'computer literacy' with a TV series called The Computer Programme and they wanted to commission a microcomputer through which the ideas developed in the programme could be demonstrated. The BBC set out a specification and the contract was won by Acorn Computers (now defunct, but living on through a number of subsidiary companies, including the chip designer, ARM). Acorn came up with a design that exceeded the BBC's requirements in almost every respect, and both the programme and the computer were so successful that 'computer' and 'BBC micro' became, for a time, almost synonymous in the popular imagination.

Alison Gazzard's book is not an account of the rise and fall of Acorn Computers and the role of the BBC Micro in its changing fortunes: it is what she describes as a 'media-archaeological approach', i.e.,

a way of excavating the archives of the components that were connected to the BBC Micro, not only in terms of hardware, software, and pieces of code, but also documented by user accounts and the multitude of platform-specific magazines that were published during the time the Micro was in use.

The results of the excavations are reported in eight chapters, grouped in three sections. The first section, Hardware and software literacies has chapters on the birth of Micro (summarised briefly above) and on the highly modular design of the computer, which allowed expansion in a number of ways, well beyond the capacity of other early microcomputers. It allowed connection of a wide variety of devices and, in fact, in the Department of Information Studies at Sheffield one of my early innovations as head of department was the introduction of a network of BBC Micros to support the work of academic staff.

In her introduction the author notes that a generation of games designers was brought up on the BBC Micro, and the second section, consisting of three chapters, is called Making and playing games. The three chapters describe the development and impact of three games: Granny's Garden, a learning game for children, which was used in schools; Elite, one of the first games to use 3D graphics and about which one observer commented, 'what David Braben managed to do with a computer with no memory and no computer power—Elite had the BBC team staggered'. Although reception of the game varied among Micro users, it was sufficiently well received to the extent that the National Elite Championship in 1985 attracted 5,000 players. The impact of the game was such that Braben established Frontier Developments, which is still producing games today. The third of these chapters deals with the game Repton, written in a month by a 15-year old game designer, Tim Tyler, which went on to be one of the most famous games in the Micro repertoire and which continues today in the form of Android Repton 1, produced by the firm that bought Tyler's game, Superior Interactive.

Throughout her discussion of these games, the author not only draws attention to the impact they made at the time, but also to the trends they set in motion and their continuing effect today and it is clear that, as far as the British games industry is concerned, the widespread adoption of the Micro was highly significant.

The final section of the book, Extending the platform, also has three chapters, two of these deal with genuine extensions in the shape of the teletext adaptor and the Domesday Project. There were, however, many ways in which the Micro could be extended: software, for example, was often supplied in hardware, in the form of chips. Thus, the word processor developed for the Micro, Wordwise, came on a chip that plugged into an expansion board in the machine and similarly with the spreadsheet, Viewsheet. This was a very efficient way of doing things since, with the software on ROM, the whole of the machine's RAM could be used for processing.

The Domesday Project has received a great deal of attention subsequently because of the BBC's decision to use a technology which rapidly disappeared from the market, the videodisc. It took years for the data to be recovered from the original discs, but, fortunately, it was and you can now search the database as originally intended, but this time, on the Web.

The final chaper deals with the legacy of the BBC Micro, in which she notes developments such as the chip designs from ARM, the successor to Acorn Computers, which power mobile phones and more today, and the development of learning devices such as Raspberry Pi and the BBC's most recent venture into computer literacy, the micro: bit. And there are even enthusiasts for computer history who continue to use the BBC Micro today.

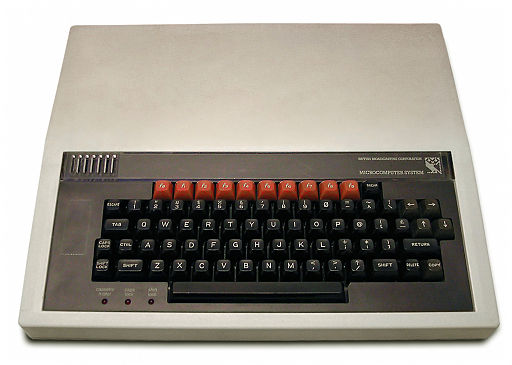

Curiously, in this otherwise excellent account of a major development in the history of computing, the author does not include a picture of the BBC Micro - so here it is.