Information behaviour of undergraduate students using Facebook Confessions for educational purposes

Richard Hayman, Erika E. Smith, and Hannah Storrs

Introduction. This research investigates the information behaviour of undergraduate students seeking academic help via anonymous posts to a university Facebook Confessions page. While Confessions pages have gained popularity in post-secondary contexts, their use for educational purposes is largely unexplored.

Method. Researchers employed a mixed methods content analysis to investigate information behaviour and the thematic contents of the 2,712 confessions posted during one academic year.

Analysis. Using generic qualitative strategies informed by constructivist grounded theory, as well as quantitative descriptive statistical procedures, researchers found that 708 (26.1%) of these confessions supported various student-student learning exchanges.

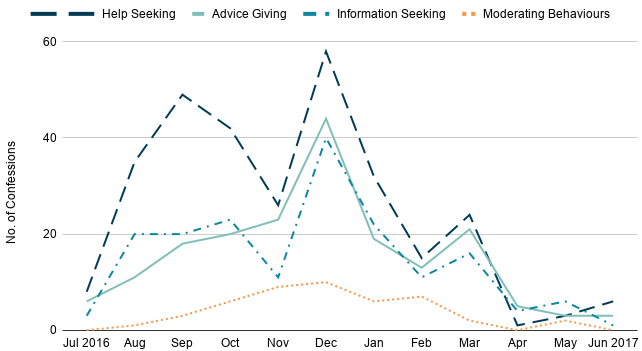

Results. Qualitative analysis demonstrated that students use Facebook Confessions to inform their undergraduate learning and support their academic experience through four main types of information behaviour: help seeking, advice giving, information seeking, and moderating behaviours. Quantitative analysis of the distribution and frequency of these types illustrated a range of information needs during particular times of the academic year.

Conclusions. While Facebook Confessions can enable rich peer-to-peer academic help seeking and other information behaviour, those in official post-secondary education roles should use caution when considering whether to engage in student-driven social media spaces. Recommendations include further development of students’ digital literacies for social media.

Introduction

This research examines undergraduate students’ use of a Facebook Confessions page at a medium-sized Canadian undergraduate university to explore the evolving and diverse nature of anonymous help-seeking and information sharing behaviour on social media. Facebook Confessions pages exist for many post-secondary institutions, and students use these pages to publicly, but anonymously, submit posts where they ask questions and share information about their personal lives and their university experiences. While Facebook Confessions pages continue to gain popularity within post-secondary education contexts, the use of Facebook Confessions for educational or academic purposes has gone largely unexplored in the literature. To address this gap, researchers investigated the following research questions:

RQ1. Do undergraduate students use the university Facebook Confessions page for help-seeking to support their post-secondary learning experiences?

RQ2. If so, what is the nature of these information behaviours and interactions, and what post-secondary teaching or learning considerations may they reveal?

By investigating these questions, this research aims to expand our understanding of teaching- and learning-related interactions that inform and reflect peer-to-peer information behaviour on a university Facebook Confessions page. Students turn to their Facebook Confessions page when seeking detailed help, to offer advice, and for general informational support. They also use Facebook Confessions posts as a way to moderate the behaviour of others. Through a mixed methods content analysis of teaching- and learning-related posts across a full academic year, our analysis shows that undergraduate students actively use their Confessions page to support their post-secondary education.

Literature review

Social media in post-secondary education

The use of Facebook and other social media technologies among university students raises complex issues for those who teach, research, and support post-secondary education, as evidenced by the plethora of research studies about social media sites within post-secondary education settings. Social media technologies are blurring the boundaries between personal and academic educational interactions (Jones, Blackey, Fitzgibbon, and Chew, 2010). Facebook has been shown to offer several benefits for post-secondary institutions, such as the ability to create strong bonds between students to help with social and academic integration (Junco, 2014) and to support academic advising (Amador and Amador, 2014). More recently, Deloatch, Bailey, Kirlik, and Zilles (2017) have demonstrated that Facebook can help undergraduate students experiencing high test-anxiety by providing peer-to-peer support. However, Facebook and other social media have also been strongly critiqued. For example, Friesen and Lowe (2012, p. 184) critique social media platforms, including Facebook, for to their commercial imperatives and the restrictive conditions that ‘significantly detract from learner control and educational use’. Smith (2016) cautions that undergraduates understand social media to be a double-edged sword, with the potential to both help and hinder their learning. It is therefore important to use a critical lens when examining the benefits and challenges of social media, such as Facebook, in post-secondary education contexts.

Facebook Confessions pages

Anonymous Facebook Confessions pages for higher education institutions are on the rise (Budryk, 2013), providing an online forum for post-secondary students to publicly, but anonymously, share their perspectives, opinions, and questions about a wide variety of topics, academic or otherwise. To date, the use of Facebook Confessions pages specifically related to post-secondary education or for other academic purposes is largely unexplored, particularly regarding online help-seeking and other digital information behaviour. While prior research on Facebook Confessions pages has examined issues of relationships, sex, and cyberbullying (e.g., Barari, 2016; Dominguez-Whitehead, Whitehead, and Bowman, 2017; Houlihan and Houlihan, 2014; Yeo and Chu, 2017), there has been little investigation of educational issues. Due to the prevalence of taboo, controversial, or problematic topics and the related potential for student conduct issues that may arise from Facebook Confessions, officials at some post-secondary institutions have tried to shut down Facebook Confessions pages associated with their institutions (Asimov, 2013; Geddes, 2015). Despite these problems, Facebook Confessions pages for post-secondary institutions still remain popular. Birnholtz, Merola, and Paul (2015) found that students’ Confessions pages were popular for discussing several taboo topics, but also included academic performance as one of nine identifiable categories, though their study does not focus on or address the teaching and learning implications in any detail. Given the prevalence of Facebook Confessions pages and their widespread presence at post-secondary institutions around the world, including their use in Australia, the United States, Canada, and the UK, there is a need for more research on the teaching and learning considerations revealed by the information behaviour on these social media sites.

Anonymity

Though the benefits and challenges that anonymity offers is not the main focus of this study, we recognize that anonymity is a key feature of original posts to Facebook Confessions in contrast to other Facebook pages and groups. Selwyn (2009) remarked that Facebook affords students the ability to hold disruptive, challenging, or resistant social identities that are contrary to traditional university norms. However, anonymous forums can also be sites of bullying, profanity, and discrimination. For example, recent news coverage of one university’s Facebook Confessions page highlighted the problem of racist comments and the related impacts on Indigenous students (Piapot, 2018). Anonymity may be a large contributing factor to negative behaviour caused by the lack of direct consequences when posting, including a perceived inability to be punished, but it can also free users to openly communicate online (Schlesinger et al., 2017) as is possible in public, offline environments through graffiti and other anonymous expressions and commentary (Rodriguez and Clair, 1999). Setting aside arguments of whether social media platforms such as Facebook offer true anonymity (since they are commercial platforms with a known interest in collecting and selling user data), we must recognize that the prospect of anonymity is one of the defining features that drives the popularity of social media interactions on popular sites such as Facebook Confessions and Yik Yak (although the latter is now defunct). Black, Mezzina, and Thompson’s (2016) study examining anonymous Yik Yak use at forty-two universities found interactions related to academic and campus life, while Clark-Gordon, Workman, and Linvill (2017) highlighted how anonymous information seeking and sharing behaviour occurs frequently among post-secondary students using Yik Yak. Other studies show that social media sites are popular among university students precisely because of features such as anonymity, ephemerality, and the hyper-locality of messages (Price, 2018; Schlesinger et al., 2017). Anonymity can be beneficial because it allows students a sense of freedom to ask questions more freely, and with less pressure to get things right. It may even encourage positive online behaviour: Birnholtz et al. (2015, p. 2621) found ‘little evidence of negativity in responses, and found most responses to be potentially useful or relevant to the questions’ on Facebook Confessions. With the disappearance of Yik Yak, which ceased operating in 2017 due to a declining user base, the popularity of Facebook Confessions as a site for anonymous university student-to-student help seeking and other information behaviour will likely continue to increase.

Key terms and definitions

Information behaviour demonstrates the ways in which people search for and use information, thereby pointing to the underlying information need at hand (Wilson, 2000). Since Facebook Confessions pages are used for sharing information, in our study we use the categories of help seeking, information seeking, advice giving, and moderating behaviours to describe this behaviour and the information needs these activities represent; we draw these categories from the data.

Within post-secondary education contexts, help seeking often occurs when students express willingness to use support services, such as counselling (Erkan, Özbay, Cihangir-Çankaya, and Terzi, 2012). As a behavioural strategy, help seeking has been associated with self-regulated learning and reflects the social nature of learning, since social interactions occur during the procurement of help (Pintrich, 2004). Puustinen and Rouet (2009) noted that human involvement is a key characteristic of help seeking, where the helper is often, but not always, an expert. Qayyum’s (2018) analysis of informal help seeking includes turning to peers, friends, and instructors beyond the classroom. In our study, peer-to-peer help seeking interactions typically elicited subjective opinions or recommendations, asked for a suggested course of action or coaching, or needed some other complex response. This characterization follows similar definitions found elsewhere (e.g., Birnholtz et al., 2015; Morris, Teevan, and Panovich, 2010).

With the advent of the Internet the differences between help seeking and information seeking have become blurred (Hao, Barnes, Wright, and Branch, 2017), especially since information seeking is often broadly defined as involving the use of any information system to satisfy a goal or need (Puustinen and Rouet, 2009; Wilson, 2000; Xie, 2009). Thomas, Tewell, and Willson (2017) note that some students believe that their peers hold certain ‘insider knowledge’ and therefore, in addition to consulting instructors or lecturers, they often prefer to consult fellow students (rather than librarians) when requesting academic help, seeking information, or locating research assistance. In a post-secondary context, Price (2018, p. 206) provides a definition of information seeking as ‘any question posed about the library, an assignment, the university, or the community that the Information Desk staff would answer’. A more expansive understanding, one that goes beyond just library or information desk contexts, is what we mean when we later refer to information seeking requests. On Facebook Confessions pages, interactions seek to satisfy an information need and typically users ask a question that has an objective, factual, or definitive answer, often one which could be readily answered by searching elsewhere. Unlike help seeking interactions, information seeking questions in this context are relatively simple and tend to have verifiable answers.

Advice giving is an alternative to help seeking among teaching and learning-focused Facebook posts. Recent research examining individual Facebook users in post-secondary education contexts reflects an affective spectrum of positive, neutral, and negative status updates (Blight, Jagiello, and Ruppel, 2015; Michikyan, Subrahmanyam, and Dennis, 2015). For example, in positive posts ‘participants shared information that was likely to elicit responses containing agreement or congratulations’ while negative ones ‘shared bad news or difficulties experienced by the poster’ (Blight et al., 2015, p. 369). This spectrum of positive-neutral-negative is reflected in the advice giving information behaviour exhibited on Facebook Confessions, whereby users post with the goal of sharing information with their peers in ways that are positive (an affirmation or encouragement), neutral (a statement), or negative (a complaint or warning).

Finally, we use the term moderating behaviours to describe the information behaviour that offers an unsolicited perspective on a situation or interaction. These posts are characterized by specific mention of an action that took place, usually directly affecting or witnessed by the person posting, and describe why a person or group of people should not (or occasionally should) behave that way again. Examining what could be considered a historical precursor to Facebook Confessions pages, Yeo, Booke, and Swabey’s (2016) research on anonymous entries in a campus newspaper found that many students used this free space in an attempt to moderate, regulate, or otherwise control other students’ behaviour. Similarly, in our study moderating behaviours were most often used to indicate when and how an event or action was disliked, inappropriate, or unwanted.

Research design

Theoretical framework

Social constructivism provides the theoretical framework for this research because it is well-suited to the nature and purpose of the inquiry. Cronin (2008) explains that ‘the socio-cultural dimensions of knowledge and the socially embedded nature of information and communication technologies (ICTs) are, and to some extent always have been, integral to the theory base of information science’ (pp. 466-467). Social constructivism allows us to consider how individual information behaviour occurs within the context of, and is thus also shaped by, various social factors (Talja, Tuominen, and Savolainen, 2005), including those within digital information environments and learning contexts. Learning and development are seen as a social-dialogical process whereby individuals actively construct knowledge and meaning through broader interactions within social contexts and environments (Driscoll, 2005; Talja et al., 2005; Jonassen and Land, 2012). In our research we incorporate this understanding of learning as a contextually embedded social-dialogical process by recognizing interactions between an individual (as expressed in a personal Facebook Confessions post) and the wider social learning community engaging with these thoughts, perspectives, and experiences via dialogue on a publicly available social media page. In educational contexts, we know that such aspects of social interaction and connectivity are increasingly extended through the use of social media technologies (Dron and Anderson, 2014). Furthermore, as a research framework, social constructivism supports inquiry into multiple meanings, views, and perspectives (Creswell, 2014), elements that we prioritized by reflecting the language that students themselves used in their confessions wherever possible.

Methodology

To investigate the nature of interactions qualitatively and quantitatively, we used an exploratory mixed methods research methodology (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018) employing mixed content analysis strategies (Hamad, Savundranayagam, Holmes, Kinsella, and Johnson, 2016). We performed qualitative content analysis on discursive textual Facebook Confessions elements using generic qualitative strategies (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016) informed by constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014) techniques. Subsequently, we conducted quantitative content analysis using descriptive statistical procedures (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison, 2011) to identify trends and patterns of information behaviour and their relationship to particular periods of time.

Setting

This study investigated social media interactions on a Facebook Confessions page for a Canadian undergraduate university. This university emphasizes engaged and personalized learning opportunities through small class sizes and low student-to-teacher ratios. During the 2016/17 academic year that was the focus of this study, the university reported approximately 9,500 full-load equivalent students and offered thirty-two majors across twelve baccalaureate degrees. This university’s semester system is similar to many other post-secondary institutions in North America, with approximately thirteen weeks of classes in the Fall semester (September through December) and again in the Winter semester (January through April), and a final examination period scheduled at the end of each semester. The university also offers shorter spring (May/June) and summer (July/August) semesters, with condensed timeframes and fewer courses available during these times.

This university’s Confessions page began in 2013. With more than 14,000 followers and over 41,000 total confessions, it has been an active, robust social media environment for student-to-student interactions. Like other Facebook Confessions pages, an important feature of this Confessions page is the anonymity of the original confession poster. To enable the original poster to remain anonymous, each confession is submitted via an anonymous online form, and page moderators (or a bot) repost that content to the Confessions page using an ID number. While the Confessions page is publicly available to be read by anyone, comments replying to the original post are not anonymous and do carry the profile of the person responding. When providing illustrative examples we have avoided or otherwise anonymized examples that might potentially include identifying information concerning the institution or individuals.

Data collection

Using the Facebook Graph API, researchers collected 2,712 original posts made to the Facebook Confessions page during the university’s academic year (July 1, 2016 to June 30, 2017). The collected content included the text of each confession (i.e., the anonymous original post), the date and time of posting, the number of textual comments submitted by other users, the number of reactions (i.e., pre-set emotive icons in Facebook that express like, love, haha, wow, sad, or angry), and also a hyperlink for each post. Researchers compiled this data in a spreadsheet, and then migrated it into MaxQDA research software for further investigation and analysis. Since original posts to Confessions pages are anonymous, demographic data regarding the users posting the original confession was not available.

Data analysis

Data analysis focused on capturing both descriptive and process elements throughout the qualitatively-driven mixed content analysis. Process coding is a valuable way to capture actions (Saldaña, 2016), and we used process techniques during coding to identify the type of information behaviour exhibited within each confession, such as whether the student was asking for advice or help or searching for a specific answer to a question. We also performed descriptive coding to capture the meaning of the content and topic of each original post, reflecting the language that students themselves used in their confessions through in vivo techniques. This article focuses primarily on the information behaviour revealed via process coding; the descriptive findings are not the focus of this report, though a brief overview of descriptive elements is available (Hayman, Smith, & Storrs, 2018).

We used negotiated intercoder agreement strategies via a consensus model (Campbell, Quincy, Osserman, and Pedersen, 2013; Saldaña, 2016) to ensure consistency and maintain rigour. Intercoder agreement procedures ensure ‘two or more coders are able to reconcile through discussion whatever coding discrepancies they may have for the same unit of text’ (Campbell et al., 2013, p. 297). Members of the research team included two faculty researcher-practitioners and one undergraduate student researcher. There were few discrepancies in coding given our familiarity with the topics and environment in question. However, since all members of the research team brought unique and valuable experience and viewpoints, we all actively and equally participated in negotiated, consensus-based discussions, and undertook thorough individual and team-based memo-ing throughout the analysis to track shared meanings and decision-making. Throughout, we used constant comparison techniques, discussed themes, categories, and topics, and brought illustrative posts to one another’s attention to ensure consensus on all elements of analysis.

We independently analysed the 2,712 original posts, following which we used negotiated intercoder agreement to develop and apply inclusion criteria. To focus solely on original posts addressing the research questions, only those confessions of an explicit academic or teaching or learning nature were included, resulting in 708 confessions that comprised the sample for the study. Posts lacking an academic or educational topic, such as personal interactions (e.g., relationships, parties, etc.) were excluded.

Each researcher independently applied codes to all 708 confessions during two comprehensive cycles of qualitative coding. We met after each round of independent coding to achieve intercoding agreement and discuss overall analysis strategies. The first coding cycle led to the development of an emergent coding scheme, with seventy-three descriptive coding subcategories organized across seven thematic areas, alongside the four behaviour processes already mentioned. We enhanced this schema with memos and scope notes that clearly defined each code. During the second coding cycle, researchers coded all 708 confessions again, this time using the refined coding scheme. To capture the main information behaviour exhibited in each confession, researchers coded each original post with one of twelve subcategories of behaviour codes, falling within one of four overarching categories listed in Table 1 below.

After establishing themes and core categories via two iterative cycles of coding, we then conducted descriptive statistical analysis (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison, 2011) on quantitative elements to determine the percentage, mean, and frequency of posts and interactions (e.g., comments, reactions) to further identify information behaviour trends and patterns during particular periods of time.

Results

Addressing the first research question, whether undergraduate students use their university Facebook Confessions page for help seeking to support their post-secondary learning experiences, the results show that they do use it for this purpose. Social media use for teaching and learning has clearly evolved: our finding that 26.1% (708 of 2,712) of Facebook Confessions posts were of an academic nature is much higher than previously shown, with Selwyn’s (2009) research showing that only 4% and Michikyan et al.’s (2015) finding that only 14% of university students’ Facebook status updates were of an academic nature.

Concerning the second research question, researchers sought to understand the nature of information behaviour and social media interactions, and to identify any post-secondary teaching or learning considerations they revealed. We identified four core categories of information behaviour among the 708 confessions: help seeking, advice giving, information seeking, and moderating behaviours, summarized in Table 1.

| Behaviour | No. of confessions | Percent of total | Key characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Help seeking | 299 | 42.2% | Question or explicit request for help; seeking a recommendation or guidance; a distinct plea. Detailed, complex, situational. |

| Advice giving | 186 | 26.3% | Expressing an unsolicited opinion, recommendation, perspective, or disclosure. Positive (an affirmation or encouragement), neutral (a statement), or negative (a complaint or warning). |

| Information seeking | 177 | 25.0% | Request for information with a clear or objective answer; often easily answerable elsewhere. Simple, straightforward, verifiable. |

| Moderating behaviours | 46 | 6.5% | Discussing conduct, action, or behaviour of others or oneself. Often describe in-person situations and a request for changes in behaviour in the future. |

| Note: Each confession was placed within only one information behaviour category. | |||

Help seeking

Confessions of a help seeking nature were by far the most common, representing 42.2% (n = 299) of all teaching- and learning-related Confessions posts. In these confessions, the poster makes a request for assistance, asking for advice, perspectives, opinions, or coaching. These requests would typically have multiple different answers rather than a single exact correct answer. Help seeking confessions divided into three thematic subcategories: a recommendation, a request for guidance, or a plea or cry for help.

Confessions seeking a recommendation were the most common help seeking behaviour, comprising 57.9% (n = 173) of help seeking posts. In many cases these posts would include a request for responses on options outlined by the confessor, to help identify the pros and cons of a potential course of action.

What's the easiest [subject] foundation [course]? Also for [other subject] I heard [course] is super easy. Is that correct? Oh and which profs would y'all recommend for each? Thanks in advance!

[W]hat is better, apply to computer sciences at [the university] and then transfer or apply to a different university and stay there for the full 4 years of the degree?

There were 85 (28.4%) requests for guidance of a more complicated nature. These confessions often asked for coaching, sought multiple perspectives or opinions on a topic, or were about topics where the response might require a plan or course of action, rather than a simple answer.

First year [bachelor degree in computer science] student here. To those of you who have done it, what is the Mandatory Work Experience like? On one hand, it most definitely does have a purpose in ensuring that not just anyone can get that degree, and I think that's great. On the other hand, it seems extremely daunting to me. After 2-3 years of education you've gotta prove you're employable. Seems pretty scary. How was it? To people who have done it or are doing it now, what is it like?

I am absolutely terrified to take business communication since I have strong anxiety for presentations to the point where I can't even speak. Any advice?

The remaining 41 (13.7%) help seeking confessions were notable for their urgent tone and content, sometimes including a plea or cry for help. These posts were characterised by an obvious struggle with a problem or other signs of distress. Many of these were for help dealing with the demands and pressures of student life, including mental health concerns.

I'm feeling extremely overwhelmed with everything. It's my first year and I need help but I don't know where to go and what to do about it. Anyone able to suggest where I can go?

This is my second year but for some reason exams took a big hit on my sanity. I've been so stressed that I will literally plan to do something and completely forget about it. This has happened all day, every day for about a month now…. Any tips to get back on track? I feel drained.

Is there anyone else at [the university] who is struggling with really bad depression, but still hanging on in school? I'm wondering, how do you manage it?

All of the help seeking confessions can also be characterised as seeking assistance that would likely be specific to the poster’s own situation or context, where there is not just one simple solution or given answer to the problem or topic at hand.

Advice giving

Confessions of the advice giving behaviour type represented 26.3% (n = 186) of overall teaching- and learning-related posts. Instead of a request seeking an answer, these confessions are characterised by an expression of an unsolicited opinion, recommendation, or point of view on a particular topic. Results showed that advice giving confessions occurred across a spectrum of positive-neutral-negative, and that the majority of confessions trended toward negative, comprising 116 (62.4%) advice giving confessions. Many of these were strikingly negative in tone, offering up condemnations of the university experience, or making specific reference to courses, professors (i.e., faculty), or other students.

University is basically sitting in different places with your laptop, paying thousands of dollars to have pre-exam panic and post-exam depression happen to you, working tirelessly in labs and on research projects, only to end up not being hires and living in your parents basement after graduating. Now don't call me a killjoy, I'm just being a blunt realist.

I hate it when professors think that their class is the most important, or the only, class that their students are taking. Please get a handle on your egomania.

Positive opinions regularly expressed encouragement or motivation, or made an exclamatory or highly affirmative comment on a topic or experience. Though it is encouraging to find several kinds of constructive, affirmative online behaviour among students’ confessions, only 27 (14.5%) of the advice giving interactions fell on the positive end of the spectrum.

Hey, you're doing better than you think.

It's the last day of class! Everyone just let loose and relax now. No more stress! :D

Grinding out courses in Summer? Keep going! Getting closer towards that goal friends!

The remaining 43 (23.1%) advice giving confessions were fairly neutral in tone and were often simple statements or opinions. Overall, just as Blight et al. (2015) found in their spectrum of indirect Facebook statuses, advice giving confessions in our study were likely to be attempts to seek validation, encouragement, acknowledgement, or further advice via comments or reactions. Further discussion of the engagement with advice giving posts through reactions and comments can be found below.

Information seeking

A third common behaviour was that of information seeking confessions representing 25% (n = 177) of the total. These posts are distinguished by the relative simplicity or straightforwardness of the request, especially when compared to the complex nature of help seeking posts. For example, the following requests posted to the Confessions page could just have easily been answered with a quick search of the university Website or consulting with the relevant service or department.

When does school start?

Any way to get office 365 for free through [the university] that I don't know about? Help please!

When a class still says professor: TBA, when do you normally find out who your professor is?

While some information seeking requests were related to assessment or research, many others related to being a student and navigating university processes, programmes, and degree requirements. Nevertheless, posts of this nature had a definitive and verifiable answer to the information need at hand.

Moderating behaviours

Finally, a fourth category of moderating behaviours emerged through coding and analysis. Though this category was initially unanticipated by the researchers, 6.5% (n = 46) of posts demonstrated moderating characteristics so these confessions warranted their own category. In the case of teaching and learning impact, many of these reflected behaviour that was occurring in the classroom or other studying environments:

I can't hear or understand anything that my teacher is saying because people are literally talking over her explaintions. Seriously people, have some fucking respect. If you don't want to learn then don't fucking go to school.

It is a goddamn physics class why must you always try to bring in politics or gossip mid lecture with the professor. Shut up and let him teach!

[The university] silent study area defection: Talk on your phone loudly, laugh loudly and not care about those around you. Fuck you to those that comment below about moving somewhere else, $750 a class I should be able to hear myself think in a silent study area.

These examples are illustrative of moderating behaviour confessions and often show the poster calling out or shaming others. Interestingly, we also found similar confessions that included a moderating effect on oneself.

I always feel like I'm bugging the people who sit near me in class with my excessive leg jiggling and constant fidgeting, but I just can't sit still for more than 10 minutes at a time.

Finally, in some cases the admonishments are downright inappropriate, akin to cyberbullying.

To the two slob kabobs, twin wannabes in one of my classes....people can see you talking about others and laughing at them to yourselves. And you're wanting to be teachers? Wow. Grow up[…].

In fact, cyberbullying and other inappropriate comments appeared throughout the confessions. We identified discussions and behaviour that simply would not be tolerated in classrooms or other teaching environments. Anonymity is likely a factor here, since some students did not shy away from expressing overt or indirect sexism, racism, and other forms of discrimination in relation to teaching and learning contexts.

Frequency and distribution of posts

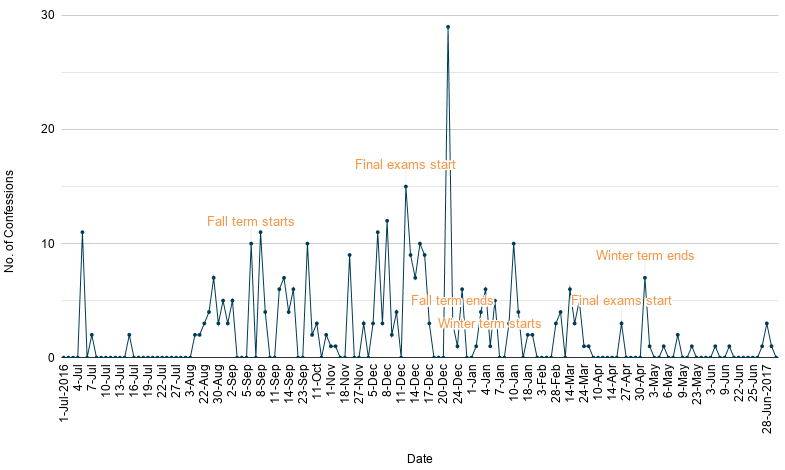

Examining the frequency of confessions over the course of the academic year reveals when particular types of teaching and learning posts were trending. Figure 1 shows expected periods of minimal activity in July/August 2016, when only a limited number of classes are offered during the summer. Activity then increases in mid-August when students begin preparing for the fall semester. We again see low activity in May and June 2017, over the quiet spring semester, when fewer courses are offered and, consequently, fewer students are formally engaged at the university.

There is considerable Confessions activity in December 2016 during the final exam period and the end of the fall semester, with a corresponding increase in help seeking, advice giving, and information seeking during this period. The large spike in activity at the end of the exam period largely reflected confessions focusing on complaints, regrets, and questions about students’ final grades, as many were seeing the results of their efforts toward completing courses and final assignments.

Love it when you're less than 0.5% away from the next highest letter grade, and your prof doesn't bump you up. Not even being "entitled", with proper rounding my grade it would have been a 95.6 and I got an A, not an A+ gr8

Is a 65 in a first year business course really that bad?

Several posts expressed concerns about whether their fall course grades would be good enough to qualify for winter courses. Other end of semester trends included discussions of registration for winter semester courses, particularly by those who had procrastinated.

Anyone know how to register for a class thats full? I've talked to the prof and they said yes but do i have to go to the registrar now? Thanks a ton

Can you still add and drop classes? There is one class I want to drop and take another one, so can I still do that? I was first on the waitlist for one class but after the last day to add your name to the waitlist I was taken off that list (I also noticed that all waitlists were cleared too).

Moderating behaviour confessions did not reflect the same dramatic spike during the fall semester exam period seen with the three other categories, we found evidence of an overall increase in moderating behaviour posts leading into December.

Engagement

A benefit of using the Facebook Graph API to create our data exports is the inclusion of data on comments and reactions on each Confessions post. This allowed us to further investigate how users of the Facebook Confessions page engaged with the confessions posted by others. Across all 708 confessions there were 2,988 comments and 2,766 reactions, with each teaching- and learning-related confession post having on average four comments (M = 4.22, SD = 4.34) and four reactions (M = 3.91, SD = 9.50). Table 2 below displays the mean and standard deviation of comments and reactions for each behaviour category, as well as for these values when all behaviour are combined.

| Behaviour | No. of comments | No. of reactions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Help seeking | 5.01 | 5.10 | 1.30 | 2.60 |

| Advice giving | 3.72 | 4.17 | 10.40 | 15.58 |

| Information seeking | 3.40 | 2.82 | 0.54 | 1.23 |

| Moderating behaviours | 4.28 | 3.63 | 7.50 | 9.71 |

| All confession posts | 4.22 | 4.34 | 3.91 | 9.50 |

As shown in Table 2, help seeking confessions have a higher mean number of comments, illustrating a higher response from other users commenting on these types of posts. This may be due to the interrogatory nature of such confessions, such as asking an open-ended question or requesting an opinion, therefore prompting other Facebook Confessions users to engage by offering their answers. Concerning reactions, advice giving confessions generated a higher mean number of reactions than posts in the other categories, with the next highest mean for reactions being in the moderating behaviours category. This could be because offering unsolicited perspectives tend to generate further opinions (e.g., agreeing or disagreeing) among other users, and reactions allow users engaging with the Facebook Confessions page to indicate their response via emoticons without having to formulate a comment.

We also analysed user engagement by looking at the number and percentage of confessions that met or exceed the overall average of four or more comments or reactions. Most of the 305 posts that met or exceeded this threshold for comments were in the help seeking category (n = 153, 50.2%). Advice giving confessions (n = 70, 23%) also generated a high percentage of comments, followed by information seeking (n = 58, 19%) and moderating behaviours (n = 24, 7.9%). We also found 179 confessions meeting or exceeding the overall average of four or more reactions. Of these, most were in the advice giving category (n = 118, 65.9%), while help seeking (n = 31, 17.3%) and moderating behaviours (n = 28, 15.6%) confessions had a similar percentage of reactions, and information seeking (n = 2, 1.1%) made up only a small percentage of the total. The low number of comments and reactions for posts in the information seeking category is likely because direct, straightforward types of questions that have relatively simple answers tend not to generate an emotive response.

Discussion

Benefits and challenges of anonymity

Anonymity can enable users to share information or questions without repercussions, so that struggling students can seek advice, express concerns, or ask questions without facing embarrassment or stigma. The anonymity that comes with Facebook Confessions may be one reason why we see a higher number of posts and interactions surrounding teaching and learning issues than has been shown in prior Facebook status updates research. Anonymity could be particularly important for those students seeking help for their well-being without identifying themselves, especially in the case of students using confessions as a distinct plea or cry for help. On the other hand, our findings illustrate that some confessions crossed the line into overt cyberbullying or racism and demonstrate that anonymity continues to have several negative consequences. Ultimately, students or educators who are enthusiastic about the efficacy or benefits of anonymous peer-to-peer support via Facebook Confessions must be just as alert to the potential detrimental effects that anonymity may generate.

Implications

In their study of college student perceptions of social networking and what they call the Facebook effect, Hurt et al. (2012, p. 14) stated that ‘By meeting students where they are, college instructors increase the likelihood that students will be more motivated to engage with their peers and course material’. However, in light of this study’s findings and recognizing the double-edged nature of social media, we caution those in post-secondary contexts to carefully consider whether and how they should meet students where they are, in a Facebook Confessions page. Given that Facebook Confessions is decidedly outside of official social media channels managed by the university, a key value of this peer-to-peer focused online space is that it is created for students and run by moderators who do not represent the university. Indeed, several recent studies have shown that while students may use social media with each other, they are often not comfortable using Facebook with those in official roles, such as faculty (Gettman and Cortijo, 2015; Jones et al., 2010; Smith, 2016). Since an increase in an official university presence on Facebook Confessions would infringe on this separate social media space that students have created for themselves, we recommend a cautious approach for those in official university positions who are considering engaging directly through Facebook Confessions since students would be unlikely to welcome an official presence in their self-created space.

Yet there is still merit for those who work in post-secondary education to understand Facebook Confessions pages and to build institutional or local awareness regarding when certain behaviour is more prevalent or when certain topics are trending. In this way, faculty and staff providing post-secondary support services may use evidence from research on Facebook Confessions as an opportunity to better understand the academic needs of students at their own institutions. For instance, increased awareness through general observation of trends in the content and types of interactions occurring on the local Facebook Confessions page would enable those providing post-secondary education support services to further understand topical or timely student issues and pressures. Such observations in research and practice could lead to targeted messaging and communication strategies that meet students at their point of need, delivered through Facebook Confessions and existing channels in ways that could be more impactful and timed to address certain topics when they are most prevalent.

There would also be benefit in creating educational opportunities that enable students to develop and apply the knowledge and skills they need to navigate this complex world of social media. For example, at many institutions (including this one) where some students act as peer educators, tutors, and mentors, these individuals could be trained to actively use Facebook Confessions as part of their peer support roles to provide links to information about relevant university services for common needs, such as mental health support, writing services, or employment opportunities.

Results of this study also reinforce findings from our earlier research (Hayman, Smith, & Storrs, 2018; Smith, 2017) underscoring a need to help students build digital literacy with the social media technologies that they already choose to use for their own teaching and learning purposes. Although these social media interactions, including those on Facebook Confessions, often occur outside of the formal curriculum, competencies in digital literacy include an ‘awareness of “people networks” as sources of advice and help’ (Bawden, 2008, p. 20). As such, there would be merit in fostering digital literacy that connects with and expands upon critical media education and information literacy instruction, providing curricula that develops all students’ abilities to safely and effectively navigate the benefits and drawbacks of using people networks as sources of information, help, and advice, particularly in the context of social media sites like Facebook Confessions.

Limitations and future directions

Since original posts made to the Facebook Confessions page are anonymous, data about the original poster is unknown, limiting our ability to definitively confirm that these posts were contributed by current or potential students at the institution. We have mitigated this limitation by examining in detail the nature and content of posts on a Facebook Confessions page for a specific university, and this data supports the conclusion that the majority of posts are from current or prospective students.

Given that this study examines a Facebook Confessions page for a medium-sized undergraduate-focused post-secondary institution in Western Canada during one academic year, the findings cannot be assumed to be transferable or generalizable beyond this timeframe, to particular student populations, or to other post-secondary education contexts, such as a larger research university. This limitation leads to possible directions for future research, such as examining different types of post-secondary institutions, or another year of Confessions posts, to see if similar behaviour and themes emerge. Our informal scans of several other post-secondary institutions’ Confession pages, including from universities in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada, point to evidence of similar interactions elsewhere, although we emphasize that further research into these topics and issues is needed.

Future investigation into the use and broader implications of Facebook Confessions is necessary. Within our current institutional context, we plan to conduct further research to examine Facebook Confessions content with an expanded focus on descriptive elements. Within and beyond own our institutional context, there is also an opportunity for further investigation of interactions occurring through comments and reactions, including additional research on the nature and content of specific responses to and interactions with the original post.

Conclusion

Results of this study reveal that over one quarter of posts to a university Facebook Confessions page were of an academic nature, much higher than previous studies have shown regarding academic use of Facebook. Findings demonstrate that the Facebook Confessions is used for a range of academic help and information seeking purposes. Qualitative results demonstrate the nature of interactions on this Confessions page occurring within four information behaviour categories of help seeking, information-seeking, advice giving, and moderating behaviours. Quantitative findings illustrate the frequency and distribution of information behaviour related to these four categories as they are reflected at particular times during an academic year. Even though Facebook Confessions interactions are outside of the formal curriculum, findings from studies such as this one reinforce the ways in which many students are using social media to support their learning both informally and formally. There is a need to increase awareness of the nature of these interactions on social media within post-secondary educational contexts, and to foster digital literacy around the social media technologies that are increasingly being used by students to meet their information needs. Given the popularity of Facebook Confessions pages among post-secondary education students, and that they are used for a range of information needs related to teaching and learning, these interactions are worthy of further investigation.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

About the authors

Richard Hayman is an Associate Professor and Digital Initiatives Librarian at Mount Royal University in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. He holds an MLIS as well as an MA. Richard’s research interests include scholarly communications, evidence-based practice, and educational technologies. He can be contacted at rhayman@mtroyal.ca.

Erika E. Smith is an Assistant Professor and Faculty Development Consultant in the Academic Development Centre at Mount Royal University in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. She holds a PhD in Adult, Community, and Higher Education from the University of Alberta. Erika's research interests include digital literacies, social media in undergraduate learning, and faculty development. She can be contacted at eesmith@mtroyal.ca.

Hannah Storrs is a Research Assistant at Mount Royal University in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. She holds a BA in Psychology (Honours) from Mount Royal University. Her research interests include abnormal psychology with a focus on anxiety and depression. She can be contacted at hstor460@mtroyal.ca .

References

- Asimov, N. (2013, March 8). SF State dislikes Facebook confessions. SFGATE. Retrieved from https://www.sfgate.com/education/article/SF-State-dislikes-Facebook-confessions-4341109.php (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76v8rqDj3)

- Amador, P. & Amador, J. (2014). Academic advising via Facebook: examining student help seeking. Internet and Higher Education, 21, 9-16.

- Barari, S. (2016). Analyzing latent topics in student confessions communities on Facebook. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1506.05193 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76wbBeoVe)

- Bawden, D. (2008). Origins and concepts of digital literacy. In C. Lankshear & M. Knobel (Eds.), Digital literacies: concepts, policies & practices (pp. 17-32). New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

- Birnholtz, J., Merola, N. A. R. & Paul, A. (2015). 'Is it weird to still be a virgin?': anonymous, locally targeted questions on Facebook Confession Boards. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 2613–2622). New York, NY: ACM.

- Black, E. W, Mezzina, K. & Thompson, L. A. (2016). Anonymous social media: understanding the content and context of Yik Yak. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 17–22.

- Blight, M. G., Jagiello, K. & Ruppel, E. K. (2015). 'Same stuff different day': a mixed-method study of support seeking on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 53, 366–373.

- Budryk, Z. (2013, February 26). From behind the screen. Inside Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/02/26/college-confession-and-makeout-pages-raise-privacy-anonymity-issues (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76v943upJ)

- Campbell, J. L., Quincy, C., Osserman, J. & Pedersen, O. K. (2013). Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociological Methods & Research, 42(3), 294–320.

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Clark-Gordon, C. V., Workman, K. E. & Linvill, D. L. (2017). College students and Yik Yak: an exploratory mixed-methods study. Social Media + Society, 3(2), 1-11.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L. & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education (7th ed.). New York, NY, NY: Routledge.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Creswell, J. W. & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Cronin, B. (2008). The sociological turn in information science. Journal of Information Science, 34(4), 465–475.

- Deloatch, R., Bailey, B. P., Kirlik, A. & Zilles, C. (2017). I need your encouragement! requesting supportive comments on social media reduces test anxiety. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 736-747). New York, NY: ACM.

- Dominguez-Whitehead, Y., Whitehead, K. A. & Bowman, B. (2017). Confessing sex in online student communities. Discourse, Context & Media, 20, 20–32.

- Driscoll, M. (2005). Psychology of learning for instruction (3rd. ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc.

- Dron, J. & Anderson, T. (2014). Teaching crowds: learning and social media. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.15215/aupress/9781927356807.01 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76tpygmCC)

- Erkan, S., Özbay, Y., Cihangir-Çankaya, Z. & Terzi, S. (2012). The prediction of university students' willingness to seeking counseling. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practices, 12(1), 35-42. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ978431 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76tqH9uEG)

- Friesen, N. & Lowe, S. (2012). The questionable promise of social media for education: connective learning and the commercial imperative. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 28(3), 183-194.

- Geddes, D. (2015, March 18). Winchester University is trying to shut down a students' Facebook page featuring tales of campus debauchery. Hampshire Chronicle. Retrieved from https://www.hampshirechronicle.co.uk/news/11864472.winchester-university-is-trying-to-shut-down-a-students-facebook-page-featuring-tales-of-campus-debauchery/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76v9bHDLZ)

- Gettman, H. J. & Cortijo, V. (2015). 'Leave me and my Facebook alone!' Understanding college students' relationship with Facebook and its use for academic purposes. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 9(1). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2015.090108 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76wahVZ5N)

- Hamad, E. O., Savundranayagam, M. Y., Holmes, J. D., Kinsella, E. A. & Johnson, A. M. (2016). Toward a mixed-methods research approach to content analysis in the digital age: the combined content-analysis model and its applications to health care Twitter feeds. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(3), e60. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5391

- Hao, Q., Barnes, B., Wright, E. & Branch, R. M. (2017). The influence of achievement goals on online help seeking of computer science students. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(6), 1273-1283.

- Hayman, R., Smith, E. E. & Storrs, H. (2018). Undergraduate students' academic information and help-seeking behaviours using an anonymous Facebook Confessions page. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of CAIS/Actes du congrès annuel de l'ACSI. Retrieved from https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/ojs.cais-acsi.ca/index.php/cais-asci/article/view/977/870

- Houlihan, D. & Houlihan, M. (2014). Adolescents and the social media: the coming storm. Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior, 2(2), e105. http://doi.org/10.4172/jcalb.1000e105 (Archived at https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/psyc_fac_pubs/77/)

- Hurt, N. E., Moss, G. S., Bradley, C. L., Larson, L. R., Lovelace, M., Prevost, L. B., ... & Camus, M. S. (2012). The ‘Facebook' effect: college students' perceptions of online discussions in the age of social networking. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 6(2), 1-24. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2012.060210 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76wasukg8)

- Jonassen, D. H. & Land, S. M. (2012). Preface. In D. Jonassen & S. M. Land (Eds.), Theoretical foundations of learning environments (2nd ed., pp. vii-x). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Jones, N., Blackey, H., Fitzgibbon, K. & Chew, E. (2010). Get out of MySpace! Computers & Education, 54(3), 776-782.

- Junco, R. (2014). Engaging students through social media: evidence-based practices for use in student affairs. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Merriam, S. B. & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Michikyan, M., Subrahmanyam, K. & Dennis, J. (2015). Facebook use and academic performance among college students: a mixed-methods study with a multi-ethnic sample. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 265-272.

- Morris, M. R., Teevan, J. & Panovich, K. (2010, April). What do people ask their social networks, and why? A survey study of status message Q&A behavior. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1739-1748). New York, NY: ACM.

- Piapot, N. (2018, October 13). Indigenous students question universities' commitment to Indigenization. CBC News. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/indigenization-university-students-1.4841965 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76v9qVJ9P)

- Pintrich, P. R. (2004). A conceptual framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in college students. Educational Psychology Review, 16(4), 385-407.

- Price, E. (2018). Should we yak back? Information seeking among Yik Yak users on a university campus. College & Research Libraries, 79(2), 200-221. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.2.200 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76trFx7fU)

- Puustinen, M. & Rouet, J-F. (2009). Learning with new technologies: help seeking and information searching revisited. Computers & Education, 53(4), 1014-1019.

- Qayyum, A. (2018). Student help-seeking attitudes and behaviors in a digital era. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15, 17. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0100-7 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76trjCDE2)

- Rodriguez, A. & Clair, R. P. (1999). Graffiti as communication: exploring the discursive tensions of anonymous texts. Southern Journal of Communication,65(1), 1-15.

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Schlesinger, A., Chandrasekharan, E., Masden, C. A., Bruckman, A. S., Edwards, W. K. & Grinter, R. E. (2017). Situated anonymity: impacts of anonymity, ephemerality, and hyper-locality on social media. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 6912-6924). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025682 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76trupCUZ)

- Selwyn, N. (2009). Faceworking: exploring students' education‐related use of Facebook. Learning, Media and Technology, 34(2), 157-174.

- Smith, E. E. (2016). 'A real double-edged sword': undergraduate perceptions of social media in their learning. Computers & Education, 103, 44-58.

- Smith, E. E. (2017). Social media in undergraduate learning: categories and characteristics. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(1), 12. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0049-y

- Talja, S., Tuominen, K. & Savolainen, R. (2005). 'Isms' in information science: constructivism, collectivism and constructionism. Journal of Documentation, 61(1), 79-101.

- Thomas, S., Tewell, E. & Willson, G. (2017). Where students start and what they do when they get stuck: a qualitative inquiry into academic information-seeking and help-seeking practices. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(2), 224-231.

- Wilson, T. D. (2000). Human information behavior. Informing Science, 3(2), 49-56. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.28945/576 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76ts2jzUk)

- Xie, I. (2009). Information searching and search models. In M. J. Bates & M. N. Maack (Eds.), Encyclopedia of library and information sciences (3rd ed., pp. 2592-2604). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Yeo, M., Booke, J. & Swabey, A. (2016). Shut the f# $%* up: forty years of student writing in an anonymous forum. Radical Pedagogy, 13(2), 56-74.

- Yeo, T. E. D. & Chu, T. H. (2017). Promoting hook-ups or filling sexual health information gaps? Exploring young people’s sex talk on Facebook. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on social media & society (pp. 1-4). New York, NY: ACM.