Synthesizing or diversifying library and information science. Sketching past achievements, current happenings and future prospects, with an interest in including or excluding approaches

Keynote address at the CoLIS 9 conference, Uppsala, June 27, 2016

Louise Limberg

Honoured guests, dear colleagues, dear hosts!

Thank you for inviting me to speak at this CoLIS 9 conference. I am honoured and pleased to present some thoughts and ideas to you, mainly based on my long experience with library and information science as a research field – I so to say grew up and aged with it.

For this talk, I have grappled with some basic questions as regards the status and development of our discipline. These include: How do we shape library and information science as an academic discipline? What points of departure have we used‒ looking back to the first CoLIS conference in 1991? How do we continue building? What shifts or controversial interests concerning theoretical, empirical and political issues are there to be dealt with? These are some questions that I’ll touch upon in my talk. And, as you will see, I find this conference essential for such a discussion.

My plan is to bring up a number of topics on the following themes, all relating to the discipline of library and information science:

- common core vs. open embrace

- conditions for upholding and developing an academic discipline

- my own research on information seeking and use, and learning

- from information literacy to media and information literacy: the political relevance of library and information science research

- conclusions and looking ahead: risks and possibilities. What can be said about library and information science as of today and tomorrow? I’ll give it a try from a Swedish/Scandinavian vantage point, starting with a short retrospect of 25 years.

Quick retrospect

Today we open the 9th CoLIS conference. The first CoLIS conference happened in Tampere in 1991. That same year Swedish library and information science was formally born, or institutionalised, through the call to the first Swedish chair for a professor of library and information science at the University of Gothenburg. This indicates that Swedish library and information science is a youngster in an international context. The first call defined library and information science in the following terms:

The discipline takes its point of departure in problems related to the mediation of information or culture, stored in some form of document. The objects of study are processes such as information provision or the mediation of culture, as well as libraries and other institutions with similar functions, involved in this process. The discipline has connections to a range of other disciplines within the social sciences, the humanities and technologies. (FRN 1989, p. 85, my translation)1

It is worth noticing, contrary to mainstream library and information science texts at the time, that this definition focuses on both processes and institutions and insists on both information and culture. Leading library and information science treatises of the period, more often than not, focussed on information as a core concept and information processes as research objects, and did not explicitly name any institutions, nor arts or culture. The Swedish definition further insists on library and information science as a multidisciplinary field across the social sciences, the humanities and technologies. This is markedly different from the central international texts on library and information science as a discipline in the early 90’s, where information science was presented as a unified discipline or on its way to becoming one (Belkin 1990; Ingwersen 1992; Ingwersen and Järvelin 2005).

It seems clear from the CoLIS 1991 proceedings (Vakkari and Cronin 1992) that the then prevailing aspiration was to establish a common core, to synthesise rather than open up for various viewpoints or perspectives, where the cognitive viewpoint, inspired by cognitive psychology (Belkin 1990), was one such powerful framework. As a whole, the proceedings are highly conceptual; the only empirical studies presented are overviews of library and information science research. There are traces of lack of self-confidence. For example, in his opening speech Pertti Vakkari emphasised the “need for LIS to improve the quality of research” (Vakkari 1992, p. 3). He went on to state that the purpose of the conference was to clarify the conceptions on the object of research, on the scope and the central phenomena of library and information science from three perspectives; social institutionalisation, cognitive institutionalisation and the nature of the discipline (ibid. p. 2-3).

Domain analysis (Hjørland and Albrechtsen 1995; Hjørland 2002) was developed by Birger Hjørland from the mid 90’s as a competing theoretical approach, not acknowledging cognitive psychology as a relevant framework, and instead suggesting social aspects of information science as foundational. However, domain analysis was based on a similar ambition to create a common theoretical framework for the discipline of information science.

Implications of these and similar theoretical and synthesizing approaches to library and information science were that they would provide possibilities for including or excluding what belonged and what did not, and thus for building the discipline according to a pattern similar to strong natural sciences, and in a positivist or realist research tradition. Furthermore, libraries as a focus of research interest were positioned as particular cases of the mediation of information, and listed with archives and museums as institutions collecting and organizing documents or objects.

The Swedish definition of the discipline, insisting on library and information science as multidisciplinary and with an explicit interest in libraries as institutions, thus seems contrary to mainstream international library and information science at the time. How come? And what happened?

One reason for the open approach to library and information science as a research field in Sweden certainly was that the professorial chair was supposed to strengthen the then 20 year old, one and only institution of library and information science education in Borås. Education for librarianship had broader interests in research than building a strong discipline. As it happened, in 1993 new legislation for higher education was implemented, prescribing that the vast majority of academic programmes were to be organised as bachelor, master and Ph.D. exams. To continue education in librarianship according to this new, and yet traditional, academic structure entailed major reshaping of the old Borås programme in librarianship. This was perfectly suited to the establishment of the discipline through the chair in Gothenburg, and so, close collaboration between the universities of Borås and Gothenburg was initiated and was a condition for the formation of education on all academic levels in Swedish library and information science. In 1993 the first doctoral students were admitted to the first Swedish library and information science Ph.D. programme in Gothenburg, and bachelor and master programmes of library and information science were launched at the Swedish School of Library and Information Science (SSLIS) in Borås2. We should recognise that these reforms were possible due to circumstances beyond interests or achievements in library and information science; rather a coincidental encounter between goal-related academic ambitions within library and information science and political reforms in higher education that suited these ambitions, but with no direct aim at library and information science as such.

Another reason for the open and inclusive stance to library and information science as a discipline certainly is that influential leaders in our field at the time, such as the first acting professor with a background in the humanities and the first permanent professor with a background in the social sciences, were both open to a range of different areas within the field, and had broad research interests. The same is true for the then new head of department at SSLIS, with a Ph.D. in anthropology, and who was also a talented strategist. To sum up, the combination of a broad definition of the discipline, and the attitudes and interests of the leaders who were to direct the implementation of education on all levels, including Ph.D., led to an open approach to library and information science focussing on capturing and analysing what seemed to be interesting problems to be investigated, adopting various theoretical approaches from library and information science as well as from other disciplines, and thus building the discipline according to the explicit principle “you take what you’ve got”3 as formulated by Romulo Enmark (1991).

Thus, in the early 1990’s we identify two quite opposing attitudes as regards the best way of shaping a discipline: one based on a set of common core concepts and with the overall interest in developing cohesive theory, and the other one more open both with regard to research problems and theory development. Now let us turn to some general and theoretical analyses of the shaping of academic disciplines.

Shaping an academic discipline

I guess that most of us are more or less familiar with criteria for shaping an academic discipline, and I assume that we can all agree that (library and) information science actually fulfils such criteria, of which the CoLIS conference is one good example, as an important means of communication within a discipline. Other criteria of a discipline include professorial chair, facilities such as buildings and equipment, education programmes from undergraduate to Ph.D. level. However, disciplines are very different as regards a common agreement on what they are about, ranging from physics or history to more loosely knit disciplines like sociology or education. Some disciplines are based in professions, such as medicine or law, and as such are broad and more divergent regarding the subject matter of research, according to Becher and Trowler, in their book Academic Tribes and Territories (2001, p. 35). I find such epistemological and sociological analyses fruitful for a more complex and varied understanding of what constitutes a discipline and how we may deliberate on library and information science as a discipline. According to the analysis by Becher and Trowler (2001, p. 23) “the ways in which academics engage with their subject matter, and the narratives they develop about this, are important structural factors in the formulation of disciplinary cultures. Together they represent features that lend coherence and relative permanence to academics’ social practices, values and attitudes across time and places.” This view supports the reason why the CoLIS conference (and other research conferences) is essential. This is where we shape the narrative of our discipline of library and information science!

Contrasting approaches

A major issue, linked to the contrasting views of (L)IS presented above, is that of the relationship between research, education and practice. It is obvious that the open and somewhat scattered approach, as described above, is grounded in library and information science as education for librarianship and other information professions. Historically, a large number of academic departments of information science have their background in schools of librarianship. In the contemporary discussion about library and information science as an academic discipline there still seem to be two main approaches, one aspiring to become a pure academic discipline such as physics or history, and the other to develop an academic and research based profession like medicine or law (Audunson 2007; Bates 2015; Mäkinen et al. 2016; Nolin and Åström 2010). Arguments are also presented for combining the conceptual information science approach with an interdisciplinary approach shaped to fit the broad knowledge requirements of the professional field. Such a combination would not only serve the professions but would also contribute to shaping the discipline of (L)IS, according to e.g. Ragnar Audunson (2007).

Since their transition from vocational training to academic education in the early 1990’s, the major Nordic schools in Denmark, Norway and Sweden opted for keeping a broad approach to library and information science, while Finland, where the discipline of library and information science was instituted almost a generation earlier, chose the consistent disciplinary approach, signifying information science and its core concepts as the basis and framework for research and education. According to a recent study of the history of Finnish information science this has brought about a separation between the discipline of information science and the profession of librarianship in Finland (Mäkinen et al. 2016). I’ll come back to this issue later in an outline of the current state of library and information science as a discipline seen from a Nordic horizon. First, some words on my own research, which will illustrate a close relationship between interdisciplinary theoretical approaches and an empirical basis in professional practice.

Research on information seeking and use, and learning

My research interests clearly derived from my professional experience as an upper secondary school librarian, with a desire to explore students’ various ways of learning via information seeking and use, and this has been the track that I followed from my doctoral work up until now (Limberg 1997; 1999; Limberg et al. 2012). Overall research questions have been: what and how do students learn via information practices? How does variation in information practices interact with variation in learning outcomes? What do libraries and ICT tools mean for student learning? After my doctoral work, a series of research projects have been conducted in teams or groups, often joining with learning researchers. This has led to fruitful collaboration across disciplinary borders based on inspiring combinations of theoretical approaches and varied analyses of empirical material, leading up to multifaceted findings with both theoretical and empirical relevance. Altogether we conducted a series of projects involving some 450 participants, mostly pupils, 30 teachers and 18 librarians, set in 15 schools, 16 classes, covering school levels from prep-school (year 0) to year 12, producing and analysing material from some 200 interviews, 30 blogs, 360 observations with interviews, field-notes, documents, etc. This research has been framed in various theoretical approaches such as phenomenography or sociocultural perspectives of learning. This means that the different projects have had somewhat different foci as regards research questions, methods for data collection, direction of analysis and research findings. While phenomenography focusses on variation in people’s experiences of phenomena in the world, sociocultural theory focusses on communicative interaction between people and between people and tools. Information activities are seen as shaped by and shaping the practices in which they are embedded (Limberg et al. 2012).

Major findings are that qualitatively various ways of seeking and using information closely interact with variation in the quality of learning outcomes. Three dimensions of these findings concern;

i) Information seeking linked to school tasks tends to be approached as seeking and compiling facts; students work with a variety of questions such as self-generated research questions, imposed research questions and search questions. Information is viewed as facts, but there are distinctions between various meanings of ”facts” (Gärdén et al. 2014). Facts may mean answers to simple questions, yes or no, right or wrong, when, how far? It is important, however, to realise that the notion of facts may sometimes imply material to be worked on for building knowledge or developing understandings. Findings indicate that pupils’ explorative investigations tend to be transformed into school assignments, where technologies and procedures dominate and where students’ research tasks are adapted to traditional school practices. In order to counteract this and to support students’ meaningful learning via independent learning tasks there is a need for more emphasis on various aspects of pupils’ work with school assignments. (Alexandersson and Limberg 2012)

ii) The close relationship identified between the quality of information seeking and use, and of learning outcomes was traced to variation in social and individual aspects of learning tasks. This is why our findings further indicate the importance of close interaction between pupils and pedagogues (teachers or librarians), in terms of scaffolding and advice, with a view to improving the quality of information practices and learning outcomes. Supervision and advice need to be directed at specific and varied aspects of information seeking and use during the whole work process, such as the shaping of research questions, the selection of search tools, how to do relevance assessment, evaluation and analysis of sources and with a distinct focus on interaction between information use, meaning-making and text production. This is different from general patterns of teaching information seeking, which tend to focus mainly on systematic ways of searching and selecting sources, as well as the critical evaluation of sources as a general skill.

iii) Finally, some critical features were identified relating to the interaction between students, pedagogues and tools for improving the conditions for meaningful learning via information practices. These concern a range of aspects of learning assignments: researchable questions; observation of various aspects of information seeking and use related to the specific task; interaction focused on knowledge content and task requirements; setting and negotiating learning goals; and, again, meaningful feedback to students throughout the whole work process.

As mentioned above, the various research projects providing these findings have adopted an interdisciplinary approach in close collaboration between library and information science researchers from the University of Borås and learning researchers from the University of Gothenburg. This combination improved conditions for research funding, where the overall success was the research programme “Learning, Interaction and Mediated Communication in Contemporary Society (LinCS)”, securing ample funding from the Swedish Research Council (VR) during 10 years 2006-2016. One of three major research themes in the LinCS research programme is ‘Literacies, media and infrastructures for learning’, with a focus on how learners accommodate to learning in digital environments and how they develop literacy and media skills required by, and relevant for, the new media ecology. This includes an interest in the role and use of infrastructures for learning such as libraries and electronic resources for information storage and retrieval (LinCS). This collaborative research between library and information science and learning combined theories of learning with theories and concepts of library and information science in fruitful ways. library and information science knowledge, theoretical and empirical, on information practices brought new dimensions to the study of students’ self-directed learning that learning researchers would not discern or identify. Our series of research projects seems like productive interdisciplinary research.

Information literacy – media and information literacy

It seems obvious that this research on the interaction between information practices and learning is close to issues of information literacy. My own history with information literacy is one of strong reluctance over many years. I hesitated to adopt the notion of information literacy as a research object, since to me, it appeared too normative and too loaded with librarians’ self-interest in promoting their own profession. My research interest in exploring variation as regards contexts, tasks and situations was also contrary to the standards set up by various professional organisations, which tend to pronounce general statements and indicate information literacy as individual and generic, regardless of context, purpose or situation. Gradually I realised and accepted that information literacy is closely connected to issues of information seeking and learning and that it might be an interesting object of research, if actually explored with appropriate theoretical perspectives, in various empirical contexts, and as practiced by people engaged with information for various purposes. (Limberg and Sundin 2006)

In my view information seeking and learning are intimately intertwined and forms aspects of information literacy. I suggest the following relationship (cf. Limberg 2009);

- Information literacy as seeking information for learning purposes – that is, information seeking for a purpose beyond itself (cf. Sundin and Johannisson 2005);

- Information literacy as learning information seeking and use – the idea of what people (users) learn to engage purposefully with information (cf. Bruce 2008);

- Information literacy as teaching information seeking and use – what librarians do, i.e. ”the flip side of no 2”;

- Information literacy as learning from information – concerned with ways of using information, transforming information into meaning, closely related to no 1.

Obviously, there are aspects of producing, shaping and sharing information to be added to the picture. With these various aspects of information literacy, a number of themes of information seeking and use may be explored, e.g. How is information literacy related to information mediated via various tools (books, the internet), genres (newspapers, hobby literature, academic or political sources) and modalities (writing, photo, moving pictures); what are the practices of evaluation and production of information/documents for learning purposes; what is the relationship between information literacy and other literacies (digital, media…)? Relating information literacy practices to information seeking and use research implies a move from a teaching perspective, strongly present in a lot of information literacy studies, to a learner perspective more in line with the user perspective often adopted in information behaviour or information practices research. In recent years, the concept of media and information literacy has appeared and attracted quite broad attention, insisting on issues linked to the critical use of media, and combining it with aspects of information literacy.

Political aspirations and implications

Library and information science has rarely attracted political interest, either on local, national or international levels. Just compare this lack of interest with issues of education from pre-school to university, constantly on the political agenda. For thirty years, information literacy research has been an issue for library and information science researchers (and practitioners). However, as hinted at above, since a few years back (2013 in Sweden), the concept of media and information Literacy has come forward as a political concern, where the idea is that this type of literacy is a key issue in our global and technological society, as stated by for instance UNESCO (2015).

Since this happened, in Sweden we have seen people on a high political level gathering in government offices and producing texts to consider and plan for action to promote media and information literacy in society at large. We hear politicians and other influential people state that “there is no research in this area”. It may be true that there is no (or little) research on media and information literacy in the field of media and communication or in education, which is often the perspective of the people involved. From both Swedish and international publications it seems as if interests in the media and communication field are the main players in this game (Carlsson, 2013; 2016). This appears to me like the appropriate moment for marketing information literacy research, which certainly seems highly relevant in the context. Important challenges for actors in our discipline are: How may library and information science research on information literacy serve the need for research based knowledge on issues related to media and information literacy? How may library and information science and information literacy research profit from this turn? According to Becher and Trowler (2001, Chapter 8) one criterion for prosperous research in our ‘postmodern’ time is its liaison with society beyond academe and with applicable research in various contexts. This indicates creative openings, but also reasons for serious consideration. What might be relevant research questions to explore in order to serve societal/political interests in media and information literacy? To meet this challenge, library and information science researchers will need to act strategically in relation to political goals. This may imply various activities, such as calling upon persons in power, politicians as well as influential academics, to present past accomplishments as well as ideas for further research along with suggestions for application of research findings. It may further imply redirecting goals of further research into a more political direction, as well as framing various studies in a societal context. Such political consideration and action may appear as counterproductive to strong conceptual interests in solidifying information science as a coherent discipline. However, societal and political relevance may also strengthen the position of library and information science research, possibly including conditions for funding. The use of bibliometrics as a quality indicator and criterion for funding to universities and academic research is a conspicuous example. A more discreet example is a recent study by Jutta Haider and Olof Sundin (2016) on algorithms in society, commissioned by the government office of strategic and future planning. A third recent example is a contribution from researchers at SSLIS to a government committee report on Media in society (Francke et al. 2016). I view these contributions to the public sphere, based in library and information science research, as essential for the future of our discipline. This brings us back to issues of choice as regards inclusion or exclusion of various topics or approaches in order for library and information science to prosper in the future.

Risks and potential: inclusion, exclusion, grounds for further development

As mentioned above, worries about possible success or failure of the future of library and information science are being voiced. One such apprehension is that information science might evaporate since it is so fragmented and diverse, implying a lack of identifiable core substance and object of research (Bawden and Robinson 2012, p. 335-336; Cronin 2012). Efforts are being made to establish whether library and information science is a discipline or not, and if so, what are its core concepts and the relationship between them. In a fairly recent text Birger Hjørland (2014) presents a list of ten names of the discipline and an analysis of what these names cover as research objects. He finds the situation highly problematic for information science as a discipline. In order to counteract the problem he suggests that the name of the discipline should be tied to some valid theoretical framework, since otherwise there is a risk that the discipline will die or be split up and merged into other disciplines (p. 224). Hjørland proposes the name of library, information and documentation science as a theoretically adequate name, given the core concepts of the field. However, he endorses the labels of information science and library and information science as synonyms, for practical reasons. His stance clearly represents an effort toward cohesiveness and conceptual consistency.

In a different direction, worries tend to be associated with fears of the future of professional librarianship (e.g. Cronin 2012). Concerns have been expressed about the risk of library and information science disappearing, since information technologies may lead to the waning of libraries. Likewise, many university information science departments have been merged with other disciplines, such as computer science, media and communication or business management. Recurring worries further express a concern or dissatisfaction that information science borrows and uses theories from fields outside library and information science, but that citations and references rarely take the opposite direction, from library and information science over to other research fields (Cronin 2012; Fisher and Julien 2009; Vakkari 2008).

Such worries and fears are repeatedly expressed in library and information science publications. It is rare that we read or hear of movements in the opposite direction, that is, export of library and information science research to other disciplines. I’ll provide you with some examples. For instance, I want to refer to Davide Nicolini, internationally well-known professor of organizational studies at the University of Warwick, who recently (2014) referred to a substantial body of information behaviour research as a basis for an extended study within the domain of health services research.

A sophisticated example of developing library and information science theory, not borrowing, was published in the Journal of Documentation this year by Anna Hampson Lundh and Mats Dolatkhah (2016), where they introduce dialogically based theory of documentary practices to study reading, instead of framing reading as information behaviour, as has been previously done in a number of studies. It definitely seems like a step forward not to use the concept of information as a theoretical foundation for the activity of reading. I find their analysis, including empirical example, bold, innovative and promising as regards theory development in library and information science. These are but two examples. I assume that, together, we might be able to list many more. I look forward to sharing more of this kind in the future.

I also find that during the last few years, major work to feature, analyse and discuss our discipline and its overall characteristics have adopted a broad and open rather than a strictly conceptual and narrow approach. In a meta-theoretical analysis Jan Nolin and Fredrik Åström (2010) argue for library and information science to combine convergent features for shaping a coherent discipline with open and divergent features, familiar to traditions within library and information science, and through this combination generate fruitful ideas and future research practices. Michael Buckland (2012) writing on the question of what kind of science information science can be, claims information science as concerned with cultural engagement, basing his arguments in an analysis of core concepts such as information, relevance, document; and linking information to learning and knowledge. His way of reasoning implies a clear repudiation of the cognitive turn, which he claims is still, in 2012, a dominant paradigm in information science. Instead he refers to information science writers, such as Søren Brier and Patrick Wilson, founding their views of the discipline on more humanistic and socially oriented philosophy. I find it noteworthy that this broad approach, framed in theories from the humanities and social sciences, but not neglecting the relevance of the technical sciences, seems quite similar to the original Swedish definition of the first chair for a professor.

This stance seems in line with what Becher and Trowler (2001) label a rural and divergent disciplinary community (p. 106; 188), like for instance geography or pharmacy. Moreover, it clearly seems more similar to library and information science as it appears at this CoLIS conference with 18 various themes listed in the call for papers, thus presenting a view of library and information science as a broad field of research from classical subfields such as information behaviour, knowledge organization and bibliometrics to more recent themes such as information architecture and information literacy — all belonging to the discipline of library and information science.

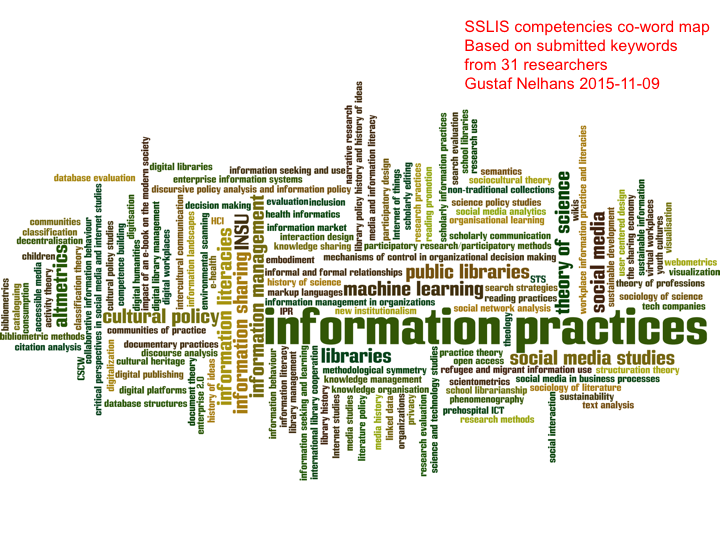

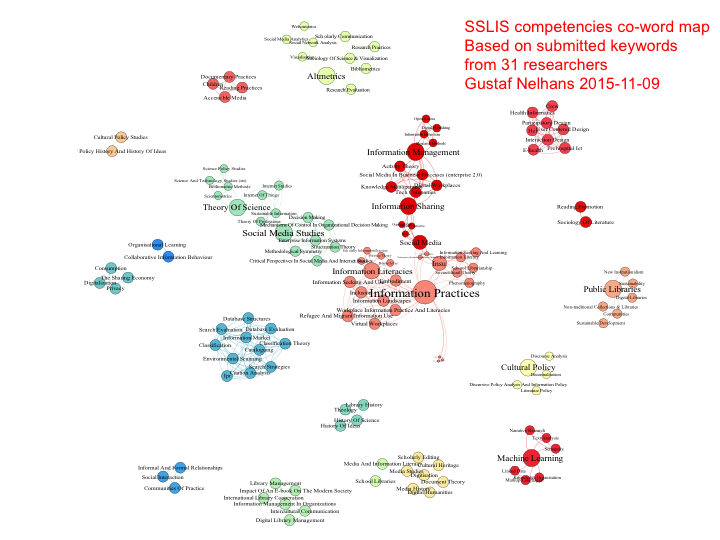

Some observations will conclude my talk. Research so far, as well as meta-theoretical analyses of scholarly disciplines, provide evidence that strong disciplines can be founded on both convergent and divergent approaches (Becher and Trowler 2001). There is plenty of evidence that the current features of the discipline of library and information science combine various theoretical approaches with a variety of empirical interests. The political relevance of subfields of library and information science such as bibliometrics or media and information literacy seems to be increasing, and should be constructively met, in my opinion. This may create new openings for stimulating developments of and through the discipline. As is clear from this presentation, I side with a broad approach to the discipline of library and information science, as long as it is conceptually well kept together, and theoretically well grounded. To finalise, I’ll present two illustrations of library and information science as it currently appears at SSLIS (Gustaf Nelhans 2015).

I find that they provide rich food for thought. The discipline certainly looks broad and varied, but at the same time with clear focus areas, combining wide space for varied interests and expertise founded in a core of common interest. We have come quite a long way since then – only 25 years ago: “We take what we’ve got” and shape it into library and information science.

1. FRN, Swedish council for planning and co-ordination of research, was a government body for funding research.

2. At the same time new library and information science programmes were opened in Lund and Umeå, and two years later also in Uppsala. A fifth site for library and information science education was started at Växjö, The Linnaeus University, in the early 2000’s.

3. The saying comes from an 18th century famous Swedish cook, Cajsa Warg, to characterise how to pick ingredients for a recipe.

Acknowledgements

I wish to extend my special thanks to two colleagues, Anna Hampson Lundh and Ola Pilerot, with whom I had creative, critical and inspiring talks that substantially contributed to this text. I also want to thank Frances Hultgren for her eminent review of the English language of the text.

References

- Alexandersson, Mikael & Louise Limberg (2012). Changing Conditions for Information Use and Learning in Swedish Schools: A Synthesis of Research. Human IT 11(2), 131–154.

- Audunson, Ragnar (2007). Library and Information Science Education — Discipline, Profession, Vocation? Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 48(2 Spring), 94-107.

- Bates, Marcia (2015). The information professions: knowledge, memory, heritage. Information Research, 20(1), paper 655.

- Bawden, David & Robinson, Lyn (2012). Introduction to Information Science. London: Facet publishing.

- Becher, T. & Trowler, P. R. (2001). Academic Tribes and Territories. Intellectual enquiry and the culture of disciplines. 2nd edition. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Belkin, Nick (1990). The cognitive viewpoint in information science. Journal of Information Science, 16, 11-15.

- Bruce, Christine (2008). Informed learning. Chicago: ALA.

- Buckland, Michael (2012). What Kind of Science Can Information Science Be? Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(1), 1-7.

- Carlsson, Ulla (2016). Medie- och informationskunnighet, demokrati och yttrandefrihet.[Media and information literacy, democracy and the freedom of speech.] Ingår i Människorna, medierna & marknaden. Medieutredningens forskningsantologi om en demokrati i förändring. [People, media and the market. Research anthology of the Media committee.] SOU 2016:30. (pp. 487-514)

- Carlsson, Ulla (Ed.) (2013). Medie- och informationskunnighet i nätverkssamhället. Skolan och demokratin.[Media- and Information Literacy in the network society. School and democracy.] University of Gothenburg: Nordicom.

- Cronin, Blaise (2012). The waxing and waning of a field: reflections on information studies education. Information Research, 17(3) paper 529. [Available at http://InformationR.net/ir/17-3/paper529.html]

- Enmark, R. (1991). Biblioteksforskning på nya vägar. [Library research on new tracks]. Svensk biblioteksforskning [Swedish Library Research] (1), 25-32.

- Fisher, Karen & Julien, Heidi (2009). Information behavior. In Annual review of information science and technology. Vol. 43 (pp. 1-73)

- Francke, Helena, Söderlind, Åsa, Pilerot, Ola, Elf. Gullvor & Limberg, Louise(2016). Biblioteken i medielandskapet: medietillgång och medie- och informationskunnighet. [Libraries in the media landscape: media access and media and information literacy.] Ingår i Människorna, medierna & marknaden. Medieutredningens forskningsantologi om en demokrati i förändring. [People, media and the market. Research anthology of the Media committee.] SOU 2016:30. (pp. 515-537)

- Gärdén, Cecilia, Francke, Helena, Lundh, Anna Hampson & Limberg, Louise (2014). A matter of facts? Linguistic tools in the context of information seeking and use in schools. In Proceedings of ISIC; the Information Behaviour Conference, Leeds, 2-5 September, 2014. Part 1, (paper isic07). Retrieved from http:/InformationR.net/ir/19-4/isic07.html.

- Haider, Jutta & Sundin, Olof (2016). Algoritmer i samhället. [Algorithms in society.] Kansliet för strategi- och samtidsfrågor, Regeringskansliet. [The Office on strategic and contemporary issues. Government offices.]

- Hjørland, Birger (2014). Information Science and Its Core concepts: Levels of Disagreement. In F. Ibekwe-SanJuan & T.M. Dousa (eds.), Theories of Information, Communication and Knowledge. (Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 34). (pp. 205-235)

- Hjørland, Birger (2002). Domain analysis in information science: Eleven approaches - traditional as well as innovative. Journal of Documentation. 58(4),422-462.

- Hjørland, Birger & Albrechtsen, Hanne (1995). Toward a New Horizon in Information Science: Domain Analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science. 46(6), 400-425.

- Ingwersen, Peter (1992). Conceptions of information science. In Conceptions of Library and Information Science. Historical, empirical and theoretical perspectives. Proceedings of the International Conference held for the celebration of 20th Anniversary of the Department of Information Studies, University of Tampere, Finland, 26-28 August 1991. (pp. 299-311).

- Ingwersen, Peter & Järvelin, Kalervo (2005). The turn : integration of information seeking and retrieval in context. Dordrecht : Springer Verlag.

- Limberg, Louise (1997): Information Use for Learning Purposes. In P. Vakkari, R. Savolainen & B. Dervin (Eds.) Information Seeking in Context (ISIC ’96) (pp. 275-289). London: Taylor Graham.

- Limberg, Louise (1999). Three Conceptions of Information Seeking and Use. In T. Wilson & D. Allen (Eds.) Information Seeking in Context (ISIC '98) Conference Proceedings. (pp. 116-132). London: Taylor Graham.

- Limberg, Louise (2009). Förord. [Preface.] In J. Hedman & A. Lundh (Eds.) Informationskompetenser: om lärande i informationspraktiker och informationssökning i lärandepraktiker. [Information literacies: on learning in information practices and information seeking in learning practices.] (pp. 7-9) Stockholm: Carlssons.

- Limberg, Louise & Sundin, Olof (2006). Teaching information seeking: relating information literacy education to theories of information behaviour. Information Research, 12(1) paper 280. [Available at http://InformationR.net/ir/12-1/paper280.html]

- Limberg, Louise, Sundin, Olof & Talja, Sanna (2012). Three Theoretical Perspectives on Information Literacy. Human IT, 11(2). https://humanit.hb.se/article/view/69

- LinCS. http://lincs.gu.se/objectives_and_aims

- Lundh, Anna H. & Dolatkhah, Mats (2016). Reading as Dialogical Document Work: Possibilities for Library and Information Science. Journal of Documentation, 7 (1), 127-139.

- Mäkinen, Ilkka, Järvelin, Kalervo, Savolainen, Reijo, & Sormunen, Eero (2016). From library and information science through information studies to information studies and interactive media: emergence, expansion and integration of information studies at the University of Tampere illustrated in word clouds. Information Research, 21(1), paper memo4. http://InformationR.net/ir/21-1/memo/memo4.html

- Nelhans, Gustaf (2015a, b). SSLIS competencies co-word map. Based on submitted keywords from 31 researchers.

- Nicolini, D., Powell, J. & Korica, M. (2014). Keeping knowledgeable: how NHS chief executive officers mobilise knowledge and information in their daily work. Health services and delivery research 2(26).

- Nolin, Jan & Åström, Fredrik (2010). Turning weakness into strength: strategies for future LIS. Journal of Documentation 66(1), 7-27.

- Sundin, Olof & Johannisson, Jenny (2005). Pragmatism, neo-pragmatism and sociocultural theory. Journal of Documentation 61 (1), 23-43

- UNESCO (2015). MIL as a Composite Concept: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- Vakkari, Pertti & Cronin, Blaise (1992). Conceptions of Library and Information Science. Historical, empirical and theoretical perspectives. Proceedings of the International Conference held for the celebration of 20th Anniversary of the Department of Information Studies, University of Tampere, Finland, 26-28 August 1991.

- Vakkari, P. (2008). Trends and approaches in information behaviour research. Information Research, 13(4) paper 361. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/13-4/paper361.html