Intelligence, academic self-concept, and information literacy: the role of adequate perceptions of academic ability in the acquisition of knowledge about information searching

Tom Rosman and Anne-Kathrin Mayer

ZPID, Leibniz Institute for Psychology Information and Documentation, Trier, Germany

Günter Krampen

University of Trier and ZPID, Leibniz Institute for Psychology Information and Documentation, Trier, Germany

Introduction

Due to an exponentially growing body of scholarly information, information literacy - often defined as the ability to successfully conduct academic information searches - is more and more considered a 'basic skills set of the 21st century' (Eisenberg, 2008, p. 39). Much effort has been put in conceptualizing and defining the construct (e.g., Lloyd, 2005; Campbell, 2008; Mackey and Jacobson, 2011), and researchers lively discuss its consequences for student achievement (Bruce, 2004; Detlor, Julien, Willson, Serenko and Lavallee, 2011) as well as didactic guidelines on information literacy instruction (Andretta, 2005; Limberg and Sundin, 2006; Streatfield, Allen and Wilson, 2010).

As most approaches on information literacy (e.g., ACRL, 2000) underline its processual nature, researchers increasingly investigate procedural knowledge about information searching (Ivanitskaya, O'Boyle and Casey, 2006; Rosman, Mayer and Krampen, under review). In contrast to declarative, more factual knowledge, procedural knowledge relates to knowledge about how to successfully conduct information searches (e.g., knowledge about how to use certain bibliographic databases). As research in the field of cognitive psychology demonstrates, procedural knowledge is probably best acquired through learning by doing (Nokes and Ohlsson, 2005). Educational psychology adds to this field an analysis of individual characteristics like intelligence or personality dispositions, susceptible to influence knowledge acquisition (Jonassen and Grabowski, 1993; Sohn, Doane and Garrison, 2006).

However, little to no research has been conducted on interindividual differences in the acquisition of procedural knowledge about information searches. We thus argue that research on the didactics of information literacy training should be complemented by research on how individual factors influence information-seeking knowledge. Results of this research may in turn help researchers and practitioners to improve their training designs or allocate students to customised training modules.

Regarding the types of individual characteristics to be considered, Markus, Cross and Wurf (1990) argued that human performance is a function of both objective skills (e.g., intelligence) and subjective beliefs (e.g., academic self-concept). Therefore, we plead for an integrated approach that considers both objective and subjective determinants of knowledge acquisition about information searching. The present paper discusses two such variables: intelligence, considered as an objective skill, and academic self-concept, its subjective counterpart.

Intelligence and information literacy

Intelligence, or general cognitive ability, is considered the most important predictor of academic success (Jensen, 1998; Kuncel, Hezlett and Ones, 2001; Mayer, 2011). Some argue that information searching requires - at least to some extent - the same set of skills that is measured by common intelligence tests, such as analytical (Lenox and Walker, 1993) and problem-solving skills (Andretta, 2005; Brand-Gruwel, Wopereis and Vermetten, 2005). This assumption gains support when taking a closer look at intelligence theory. Fluid intelligence, as measured by Raven's Advanced Progressive Matrices (Raven, Raven and Court, 1998), refers to the '… ability to decompose problems into manageable segments and iterate through them, the differential ability to manage the hierarchy of goals and subgoals generated by this problem decomposition, and the differential ability to form higher level abstractions' (Carpenter, Just and Shell, 1990, p. 429). This decomposition of a problem into smaller subproblems and the resulting necessity of organizing and managing a multitude of subgoals (the so-called goal management) supposedly plays a central role in information searching: the initial problem (e.g., 'I want to find scholarly literature on personality disorders in children'.) has to be decomposed into manageable segments (e.g., determining the extent of information need, selecting relevant databases, elaborating which functions of the databases are of use, etc.) prior to and throughout the actual search. Therefore, fluid intelligence should have some influence on a nonlinear and iterative process like information literacy (Rosenfeld, Salazar-Riera and Vieira, 2002).

The role of the academic self-concept

Many authors have argued that academic self-perceptions play a central role in academic achievement by enabling students to develop their potential (Marsh and Seaton, 2013). Students' academic self-concept is deemed to influence learning and academic performance through motivational processes like increased effort and persistence (Marsh, 1993; Bandura, 1997) as well as academic choice behaviour (Guay and Vallerand, 1996; Guay, Marsh and Boivin, 2003). Students with a high academic self-concept should therefore invest more effort in their learning, persevere in the face of difficulties, and act out of pleasure and choice. Especially this acting out of pleasure and choice is hereby hypothesised to have positive effects 'on depth of processing, retention, integration, generalization of knowledge, and thereby academic achievement' (Guay and Vallerand, 1996, p. 214).

A shortcoming of this research is that it solely focuses subjective beliefs and attitudes, neglecting individual abilities as another important predictor of academic success. Markus et al. (1990) therefore elaborate their theorizing by hypothesising that 'competence in a domain requires both some ability in the domain and a self-schema for this ability' and that 'felt competence is an essential aspect of actual competence' (p. 206). Even though individual ability is seen as a basic requirement for performance, commitment and achievement motivation can only emerge in case of a favourable view of oneself and one's abilities (e.g., a high academic self-concept or self-efficacy). If, however, students underestimate their possibilities, they will be less optimistic, devote less effort to their actions, and give up more easily in the face of difficulties (Markus et al., 1990). Hence, the under-estimation of abilities (underconfidence) may well hinder individuals to make use of their potential: high ability students should only perform better than their lower talented peers if their academic self-concept matches their ability (see also Feldhusen and Hoover, 1986). Findings that bright but low performing students (so-called underachievers) have low self-concepts can be brought forward as empirical support for the postulated negative effects of underconfidence (Van Boxtel and Mönks, 1992; Reis and McCoach, 2000).

However, this literature is somewhat one-sided, as most authors focus on high-ability students and the detrimental effects of underconfidence. A high subjective ability is seen as beneficial in all possible circumstances, as it is ascribed to promote effort, persistence, and attention (Markus , 1990). This theorizing is challenged by a growing body of literature on the detrimental effects of ability over-estimation (overconfidence). Freund and Kasten (2012) give the compelling example of someone having a car accident because of the over-estimation of his driving abilities. With respect to academic domains, it has been shown that the over-estimation of academic ability has negative effects on students' grades (Zakay and Glicksohn, 1992), learning and retention (Dunlosky and Rawson, 2012), or IT competence (Moores and Chang, 2009). These negative effects might be due to a reduction of effort as it has been shown that over-confident students prematurely terminate studying (Dunlosky and Rawson, 2012) and become less academically engaged in general (Robins and Beer, 2001). Effort calculation theory, which states that with increasing subjective ability, humans will assume less effort to be necessary for goal attainment (Heider, 1958), provides support for this assumption.

To sum up, there is an apparent contradiction between the theories of Markus et al. (1990) who state that high subjective ability always promotes effort, and Heider (1958) who argues that high subjective ability always reduces effort. In combination with the presented empirical findings, we hypothesised the following: Whenever subjects are able to realistically estimate their ability, the resulting effort will be higher than when they over- or underestimate their ability. As learning (or, more generally, performance) requires both effort and ability (Heider, 1958), the most pronounced increase of knowledge is to be expected for subjects who have a high ability and devote effort to realise their potential. Reduced effort, on the other hand, should impair knowledge development.

We thus argue that an adequate estimation of one's ability might promote knowledge development through an increase in effort. On the other hand, over- or underconfidence might impair knowledge development due to a reduction of effort. One can therefore conclude that accuracy of self-evaluations plays a major role in learning and performance (Freund and Kasten, 2012). Correspondingly, Plucker, Robinson, Greenspon, Feldhusen, McCoach and Subotnik (2004) argue: 'One needs a realistic view of one's abilities in order to capitalise on personal strengths and compensate for weaknesses' (p. 269). Hence, most pronounced knowledge development should occur when there is match between self-perceived and actual ability: A high academic self-concept enables intelligent students to make use of their potential and thus facilitates knowledge development. These effects might at least partially be due to greater effort expenditure in contrast to high ability students who underestimate their ability. On the other hand, for less intelligent students, an adequately low academic self-concept indicates that they recognise their deficits, which in turn enables them to develop at least some knowledge through compensatory effort. In contrast, less intelligent students who overestimate their potential might reduce their effort as they don't recognise their deficits and presume that they can succeed with little effort.

With regard to information literacy, knowledge development of over-confident students might be weakened by a reduction of effort through terminating all searches prematurely assuming that all relevant literature has been discovered (less learning by doing), or by simply renouncing to attend to information literacy training. On the other hand, under-confident students cannot make use of their intellectual potential because of the detrimental effects of this underconfidence on their motivation and effort. For example, they might think that no matter how much effort they invest, they won't be able to develop adequate information-seeking skills, or they might just avoid information searching at all. Students with realistic self-views, on the other hand, live up to their potential because of the resulting increased effort.

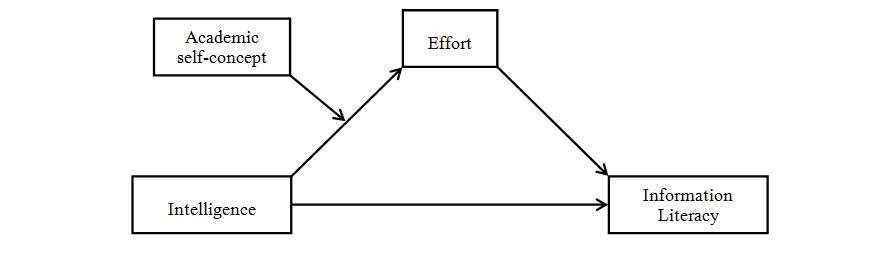

In sum, this theorizing enables to derive a moderator effect of the academic self-concept on the relationship between cognitive ability (i.e., intelligence) and information literacy: on the one hand, the positive effects of high cognitive ability have full effect if paired with a (realistically) high academic self-concept (Markus et al., 1990), whereas the negative effects of a low cognitive ability are even intensified by an overly high academic self-concept (due to the detrimental effects of overconfidence). Intelligence and information literacy should thus be positively related for students with a high academic self-concept. On the other hand, the negative effects of a lower intelligence may partially be buffered by a realistically low self-concept (and the resulting increased effort), whereas the positive effects of a higher intelligence are dampened by a low self-concept because of the under-estimation of one's ability (Markus et al., 1990). Thus, for students with a low academic self-concept, the relationship between intelligence and information literacy should be small to non-significant. A fan-shaped or even crossed interaction would result. Leclerc, Larivée, Archambault, and Janosz (2010) were able to confirm the existence of such a moderator effect with regard to math performance. With respect to our theorizing, we assume that the effect may be reproduced with regard to information literacy. Moreover, we expect that student's effort is responsible for (mediates) this moderator effect (see Figure 1).

Based on our theorising, we suggest the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Academic self-concept moderates the relationship between intelligence and information literacy: the correlation between intelligence and information literacy is higher for students with a high academic self-concept.

Hypothesis 2: The negative effects of ability over- and under-estimation on effort and motivation are responsible for this moderator effect. Thus, in a mediated moderation model, effort mediates the moderating effects of the academic self-concept on the relationship between intelligence and information literacy (see Figure 1).

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were 137 psychology freshmen from University of Trier taking part in a longitudinal study on knowledge development during the first two years of their studies. Mean age was M = 20.43 (SD = 2.53) and ranged from 18 to 31 years. Sex was distributed unevenly with 82 % females and 18 % males, which is nevertheless typical for German psychology students (Schneller and Schneider, 2005; Wentura, Ziegler, Scheuer, Bölte, Rammsayer and Salewski, 2013). Participants were recruited by means of flyers and a personalised email inviting them to take part in a longitudinal study on knowledge development. Data collection was divided into two parts. After registration for the study, subjects received a link to an online module comprising several self-report inventories, including a measure of academic self-concept. This module took approximately 30 minutes and had to be completed before attending a laboratory session in a computer lab at the University of Trier. Data from this laboratory session was collected in groups ranging from 2 to 16 participants and took approximately two hours. Among other measures, participants completed an intelligence test and an information literacy test. Participants received a compensation of ? 25 for their participation.

Measures

Information literacy was measured using the PIKE-P test (Procedural Information-seeking Knowledge Test - version for students of psychology: Rosman et al., under review; see also Rosman and Birke, in press). The 22-item test focuses procedural knowledge about various aspects of information-seeking (e.g., generation of search keywords, selection of adequate sources, utilisation of limiters and Boolean operators, etc.) by drawing on a situational judgment format. Items begin with a description of a problem situation requiring an information search (e.g., 'You need the following book: "Richard S. Lazarus - Stress, Appraisal, and Coping". How do you proceed?). Subsequently, four response alternatives (e.g., 'I look up the ISBN-Number of the book and enter it into the library catalog'; 'I try to locate and download a .pdf of the book using a web search engine'; etc.) are to be rated on a 5-point Likert-Scale (not useful at all to very useful) with respect to their appropriateness of solving the problem. Subjects' scores are obtained through a standardised scoring key which is based on an expert ranking of the appropriateness of the response alternatives. Scale validity was demonstrated in a validation study (Rosman , under review), in which high correlations (r > .60; p < .001) between the scale and scores achieved in actual information search tasks (see Leichner, Peter, Mayer and Krampen, in press) were found.

Fluid intelligence was measured by Raven's Advanced Progressive Matrices (Raven et al., 1998). Each test item consists of a visual pattern with a missing piece, and subjects are invited to complete this pattern by choosing the correct piece from a set of eight alternatives. The test consists of 32 items of increasing difficulty. With reference to the work by Hamel and Schmittmann (2006), a time limit of 20 minutes was imposed on the test. Scores were obtained by summing up the number of correctly solved items.

Academic self-concept was measured with the absolute academic self-concept scale from Dickhäuser, Schöne, Spinath and Stiensmeier-Pelster (2002), which assesses students' academic self-concept without providing a reference norm (e.g., social or individual reference). Its five items begin by a statement that has to be completed on a 7-point Likert-Scale (e.g., 'My academic ability is . low [1] - high [7]'; 'In my opinion I am . not intelligent [1] - very intelligent [7]'). Subjects' scores were obtained by calculating the arithmetic mean of the five items.

Effort was measured with the work avoidance scale of a German self-report measure (Skalen zur Erfassung der Lern-und Leistungsmotivation; SELLMO: Spinath, Stiensmeier-Pelster, Schöne and Dickhäuser, 2002). The scale consists of 8 items (e.g, 'In my studies it is important for me to do as little work as possible') that are to be rated on a 5-point Likert-Scale (totally disagree [1] to totally agree [5]). By referring to 'the goal to invest as little effort as possible' (Steinmayr and Spinath, 2009, p. 81), the scale constitutes a reverse coded (high scores = low effort) indicator for study effort. With regard to our mediation hypothesis, this reverse coding does not threaten interpretability. Subjects' scores were again obtained by calculating the arithmetic mean of all items.

Results

The following section is organized according to our hypotheses: In the first part, we will report the results of the test of the moderation hypothesis. The second part describes tests for mediated moderation. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of all study variables.

| Construct | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Information literacy | 47.05 | 7.23 | (0.50) | - | - | - |

| 2 Fluid intelligence | 21.01 | 3.72 | .011 | - | - | - |

| 3 Academic self-concept | 4.70 | 0.83 | -0.02 | 0.07 | (0.84) | - |

| 4 Work avoidance | 1.89 | 0.59 | -0.30** | 0.12 | -0.15* | (0.87) |

| N = 137; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01. | ||||||

Hypothesis 1

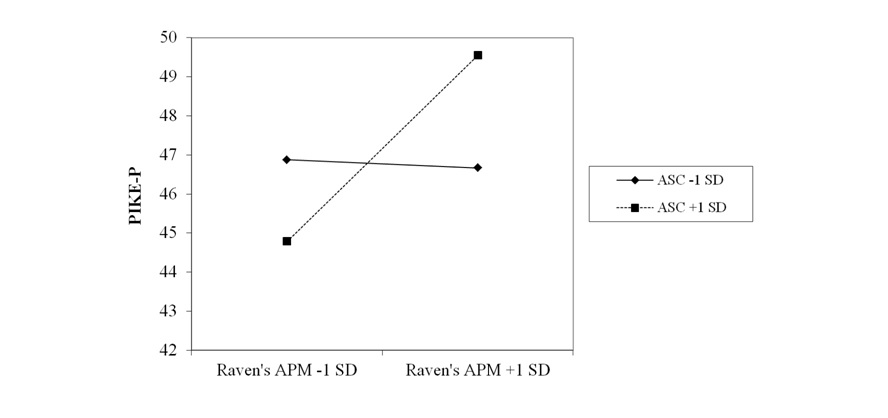

Hypothesis 1 was tested by adding an interaction term into a multiple regression predicting information literacy from z-standardised intelligence and academic self-concept scores (Aiken and West, 1991). As depicted in Table 2, the interaction term was statistically significant. An inspection of the corresponding regression plot (Figure 2) revealed that the moderator effect was in the hypothesised direction: a positive relationship between intelligence and information literacy was found for subjects with a high (+1 SD) academic self-concept, whereas the relationship between intelligence and information literacy is close to zero for subjects with a low (-1 SD) academic self-concept. The interaction was crossed (and not just fan-shaped; see Figure 2), so that information literacy for subjects with a low intelligence and a high academic self-concept is even inferior to the respective scores of subjects with a low intelligence and a (realistically) low academic self-concept. As suggested by Aiken and West (1991), the graphic interpretation was verified by a simple slope test: for subjects with a high academic self-concept, the slope of the relationship between intelligence and information literacy was significant (B = 2.38; t = 2.72; p < 0.01). For subjects with a low academic self-concept, the respective relationship was - as hypothesised - not significant. Hypothesis 1 is therefore fully supported.

| Information Literacy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | R2 | ΔR2 | |

| Block 1 | 0.01 | ||

| Fluid intelligence (z-standardised) | 0.11 | ||

| Academic self-concept (z-standardised) | -0.03 | ||

| Block 2 | 0.06** | 0.05** | |

| Fluid intelligence (z-standardised) | 0.16* | ||

| Academic self-concept (z-standardised) | 0.03 | ||

| APMxASC (interaction term) | 0.22** | ||

| N = 137; Method = Enter; β = standardised regression weight; R2 = total variance explained; ΔR2 = change in R2 from block 1 to block 2; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.) | |||

Hypothesis 2

To test for mediated moderation, we adopted the procedure by Muller, Judd and Yzerbyt (2005), which relies on multiple regression. Their first criterion for mediated moderation is that the interaction of the independent variable (intelligence) and the moderator (academic self-concept) significantly predicts the dependent variable (information literacy). As shown in Table 2, this criterion was met (see also results of the test of hypothesis 1). The second criterion requires that the interaction between independent variable and moderator significantly predicts the mediator (work avoidance). Table 3 shows that this criterion is fulfilled. The third criterion requires that the mediator significantly predicts the dependent variable while controlling for both the interactions between (1) the moderator and the independent variable and (2) the moderator and the mediator. As shown in Table 4, this criterion was also met. As a fourth criterion, it is required that the β-weight of the interaction term between independent variable and moderator is reduced when the interaction term of mediator and moderator as well as the mediator are included in the regression predicting the dependent variable (compare Tables 2 and 4). Even though it stayed significant, the effect of this interaction term on the dependent variable decreased from β = .22 (p < .01) to β = 0.18 (p < 0.05), which indicates partial mediated moderation. As Muller et al. (2005) do not provide any technique to test this decrease for significance, additional analyses were conducted by means of the PROCESS macro (model 4; manually calculated interaction term; 10.000 bootstrap samples; 95 % confidence intervals) provided by Hayes (2013). The procedure confirmed the existence of mediated moderation. As bootstrap confidence intervals of the mediated effect did not include 0 (a3b = .11; CI = 0.02 to 0.22), it can be concluded that the hypothesised mediator effect is indeed statistically significant. Hypothesis 2 is supported.

| Work avoidance | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | R2 | ΔR2 | |

| Block 1 | 0.04* | ||

| Fluid intelligence (z-standardised) | 0.13 | ||

| Academic self-concept (z-standardised) | -0.16* | ||

| Block 2 | .07* | 0.03* | |

| Fluid intelligence (z-standardised) | 0.09 | ||

| Academic self-concept (z-standardised) | -0.21** | ||

| APMxASC (interaction term) | -0.20* | ||

| N = 137; Method: Enter; β = standardised regression weight; R2 = total variance explained; ΔR2 = change in R2 from block 1 to block 2; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01. | |||

| Information literacy | ||

|---|---|---|

| β | R2 | |

| Block 1 | 0.15** | |

| Fluid intelligence (z-standardised) | 0.18* | |

| Academic self-concept (z-standardised) | -0.03 | |

| Work avoidance (z-standardised) | -0.32** | |

| APMxASC | -0.18* | |

| WAxASC | -0.05 | |

| N = 137; Method: Enter; APMxASC = interaction term of fluid intelligence and academic self-concept; WAxASC = interaction term of work avoidance and academic self-concept; β = standardised regression weight; R2 = total variance explained; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01. | ||

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to investigate whether an adequate perception of one's academic ability is essential in information-seeking knowledge development. Consistent with our theorizing, a high academic self-concept should be beneficial for students with high cognitive ability, whereas it may even have detrimental effects on lower ability students. A low academic self-concept, on the other hand, should have detrimental effects on the performance of high ability students but be beneficial for students with lower ability. This reasoning implies a moderator effect of the academic self-concept on the relationship between intelligence and information literacy (Hypothesis 1), which was supported empirically. We attributed this moderator effect (1) on the positive effects of an adequate ability self-perception on effort and motivation, and (2) on the negative effects of under- and overconfidence on effort and motivation (Hypothesis 2). A mediated-moderation analysis confirmed that effort is indeed one of the mechanisms responsible for the moderator effect postulated in Hypothesis 1, thus confirming Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 1: Moderator effect of the academic self-concept

The significant moderator effect in hypothesis 1 implies that, for subjects with a high academic self-concept, intelligence and information literacy are positively related. In the case of a low academic self-concept, however, this relationship becomes non-significant. Our results show that the findings of Leclerc et al. (2010) can indeed be generalised to the domain of information literacy. The crossed nature of the interaction (see Figure 2) indicates that a high self-concept paired with low intelligence (overconfidence) impairs performance even stronger than an adequately low self-concept together with a low intelligence. Likewise, information literacy of high ability students with a high academic self-concept is higher than the respective levels of high ability but under-confident students. The findings thus confirm that realistic academic self-perceptions are desirable.

Hypothesis 2: Mediator effect of effort on the moderator effect of the academic self-concept

Effort partially mediating the moderator effect of hypothesis 1 indicates that effort is - at least to a certain extent - responsible for this moderator effect. As long as their self-concept matches their ability, students devote increased effort to their studying, which in turn promotes knowledge development. Over- and under-confident students, however, are likely to reduce their effort, as they don't recognise their weaknesses or their potential and thus fail to act accordingly. Hence, our findings show that the common assumption of a high academic self-concept (or, more generally, high self-confidence) always being beneficial (e.g., Marsh and Seaton, 2013) is short-sighted. In fact, our data suggests that overconfidence (overly high academic self-concept) leads to a decrease in both effort and performance relative to students who assess their ability in a more realistic way.

Limitations and implications for further research

Even though we took great care in collecting, analysing and interpreting our data, some potential limitations to our efforts should not be withheld. First, Cronbach's Alpha of the PIKE-P test was very low in the present study. As the test has proven to be reliable with two different samples of psychology students (see Rosman et al., under review), this might be caused by the reduced variability in our data as our sample only comprised freshmen. With respect to a low reliability usually deflating (and therefore masking) relationships between variables (Carmines and Zeller, 1979; Schmitt, 1996), we nevertheless do not expect this issue to severely bias our findings.

A more serious limitation, however, concerns our sample, as we solely investigated psychology freshmen from one single university. The uneven sex distribution - although typical for German psychology students - aggravates this limitation and impairs generalizability. Additionally, one can argue that freshmen are not well-suited to investigate the development of information-seeking knowledge, as they presumably do not have much experience in information searching yet. However, with a certain amount of variance and no floor effects in our data, it is plausible to assume that most students had already acquired basic information-seeking knowledge prior to and in the beginning of their studies (e.g., by performing scholarly information searches during their last high school years).

A third potential limitation is that the PIKE-P test used to investigate information literacy solely focuses procedural knowledge about information searching as such, leaving aside evaluation and utilisation of the discovered information. Thus, our study does not account for the whole breadth of the information literacy construct as defined by the ACRL (2000).

Finally, our mediated moderation analysis showed that effort is only partly responsible for the moderator effect. Even though partial mediation is much more common than full mediation (Hayes, 2013), it could prove fruitful to investigate other variables that might account for the moderator effect of the academic self-concept. For example, Markus et al. (1990) argued that under-confident students are more hesitating and set less challenging goals. A mediated moderation analysis including these variables could shed more light on the mechanisms of the positive effects of an adequate self-assessment. Furthermore, research should concentrate on replicating our findings in different domains and with different information literacy measures. As our theoretical reasoning about the beneficial effects of an accurate self-perception can easily be expanded to other domains than information literacy, replicating our findings with regard to knowledge development in other disciplines (e.g., physics, math or languages) or study achievement in general could also prove fruitful. Additionally, longitudinal studies investigating the impact of self-perception adequacy on knowledge development are desirable.

Practical implications

Several conclusions can be drawn from the present investigation. First, the findings explain that an accurate ability self-perception is preferable over excessively high self-perceptions: a high academic self-concept is only beneficial if these self-perceptions are realistically founded. Efforts to identify unrealistic self-perceptions should therefore be made. Additionally, as a high academic self-concept enables high ability students to make use of their potential, these students should be subject to interventions that foster their self-perceptions. An approach that directly enhances academic self-concept was developed by Craven, Marsh and Debus (1991) and focuses on performance feedback through effective praising strategies (e.g., credible praising with respect to specific accomplishments and attributing these accomplishments to effort and ability; Brophy, 1981). A second, indirect approach of fostering students' academic self-concepts consists in the training of academic skills (e.g., learning strategies, problem solving, or information skills). In accordance with the so-called reciprocal effects model, the resulting academic success in turn positively reflects on the academic self-concept (Guay et al., 2003).

With regard to low-ability students who overestimate their ability, the situation is more precarious. Pajares and Kranzler (1995) strongly discourage efforts to directly lower such students' self-perceptions (for example through negative feedback). As such methods might lead to anxiety and disengagement, we fully agree with their point. As the present paper points out that over-confident students likely do not invest enough effort in academic matters, communicating information searching as being a rather difficult task (which surely is the case) might however make sense. Consistent with effort calculation theory (see above; Heider, 1958), an increase in subjective task difficulty will - all other things being equal - lead to increased effort and thus better learning.

In sum, when developing information literacy instruction programmes, we have to keep in mind that what is good for some students (e.g., praise for under-confident students) might be bad for others (e.g., over-confident students). Practitioners should therefore focus on the assessment of objective as well as subjective individual abilities and give individually tailored support and performance feedback. To teach procedural knowledge about a complex skill set like information literacy, it is of crucial importance that students actively participate in the training, for example by conducting their own searches, and receive feedback about their performance to be able to develop realistic academic self-perceptions (see also Rosman, Mayer and Krampen, 2014). Under such conditions, the benefits of learning by doing have full effect. To conclude, we plead for a stronger integration of individualised information literacy instruction into college and university courses, so that high ability students can reach excellence and less fortunate students are not unnecessarily impeded in their skill development.

Acknowledgements

Research was funded by the German Joint Initiative for Research and Innovation with a grant acquired in the Leibniz Competition 2013.

About the authors

Tom Rosman is Research Associate and PhD student at the Leibniz Institute for Psychology Information (ZPID), Trier, Germany. He received his diploma in Psychology from the University of Trier. His research focuses on information behaviour, epistemological beliefs, and knowledge development. He can be contacted at: rosman@zpid.de

Anne-Kathrin Mayer is head of the Research Department at the Leibniz Institute for Psychology Information (ZPID), Trier, Germany. She received both her diploma in Psychology and her PhD from the University of Trier. Her research focuses on information behaviour, psychological assessment, and intergenerational relationships. She can be contacted at: mayer@zpid.de

Günter Krampen is Professor for Clinical Psychology, Psychotherapy, and Scientometrics at the University of Trier, Germany, and director of the Leibniz Institute for Psychology Information (ZPID) in Trier. He received his diploma in Psychology from the University of Trier and his PhD from the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany. His research focuses on clinical psychology, psychological assessment, scientometrics, and history of psychology. He can be contacted at: krampen@zpid.de