Untangling the evidence: introducing an empirical model for evidence-based library and information practice

Ann Gillespie

Queensland University of Technology, 2 George St., Brisbane, QLD 4000, Australia

Introduction

This research is the first to investigate the experiences of teacher-librarians as evidence-based practitioners. The findings of this research and the associated model (Gillespie, 2013) demonstrate that evidence-based practice is holistic. This paper presents the empirically derived model which emerged from this research. In particular it explains the two distinct ways that teacher-librarians experience evidence-based practice. The two overarching actions of engaging and encountering describe this experience. The paper begins by providing a context for this research, an overview of the literature explains the research approach leading to a description of the empirical model. A discussion of the implications is followed by recommendations for a way forward for teacher-librarians, and the library and information services sector in general.

This study responded to the findings of the Inquiry into school libraries and teacher-librarians in Australian schools (Australia. House..., 2011). These initiatives have raised awareness of school libraries, and of the role of teacher-librarians and their impact on student social, cultural and academic achievement. However, their future sustainability is under scrutiny.

In Australia, there are several hundred professional teacher-librarians with dual teaching and librarianship qualifications across all school sectors. The Australian School Library Association (2009) in its Statement on teacher-librarian qualifications recommends that:

The person responsible for leading and managing the school library should be a qualified teacher-librarian. As a member of a school's teaching team, the teacher-librarian has a role in the planning, implementation and evaluation of educational policies, curricula, outcomes and programs, with particular reference to the development of students' information literacy.

teacher-librarians have a multi-faceted role but central to the role are the contributions to the learning goals of the school. teacher-librarians with dual qualifications are professionally balanced between education and librarianship, and can draw on both areas of expertise to support teaching and learning in schools. The Australian School Library Association (2012), in its policy document Advocacy: what is a teacher-librarian?, describes teacher-librarians as having three major roles: as curriculum leaders, information specialists and information services managers.

The model for evidence-based practice presented in this paper makes a research contribution to the early development of a theory for evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians. Research is the foundation of evidence-based practice (Booth, 2010b; Todd, 2002) yet very little exists that can support teacher-librarians in being evidence-based practitioners. In presenting this model, practitioners can gain a deeper understanding of the theoretical aspects of evidence-based practice before moving onto the many approaches possible for teacher-librarians to be evidence-based in their practice.

Literature review

To understand the experience of evidence-based practice in teacher-librarianship, it is necessary to first understand the origins and development of evidence-based practice in other fields. This review explains how evidence-based practice first emerged in medicine, then diversified into healthcare, health libraries and education, and eventually into teacher-librarianship. It shows that there is little research that focuses on teacher-librarians as evidence-based practitioners.

Evidenced based practice - origins and definitions

It is from medicine that the concept of evidence-based practice first emerged and the most widely cited definition comes from this field. Evidence-based medicine is the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research (Sackett, Rosenberg, Muir, Gray, Haynes and Richardson, 1996, p. 71).

Although Sackett et al.'s definition (1996) suggests that evidence-based medicine should not entirely rely on randomised controlled trials, in practice, evidence-based medicine places evidence in a hierarchy, with scientific, randomised controlled trials held in the highest regard. As the practice of evidence-based medicine has gained acceptance, it has been commonly assumed that evidence-based practice has a basis in research evidence, particularly that in the quantitative tradition (Rycroft-Malone et al., 2004).

Traditionally, evidence-based medicine has focused on decision making, with an intention to use research to empower staff for best patient advantage (McCormack, 2006). When applied to nursing and healthcare, however, there has been a change in focus, where evidence is 'contextually located and embedded in multiple cultures' (McCormack, 2006, p. 90). Hence, within the nursing and healthcare sectors there is an emphasis on implementation and practice, taking into consideration the context and environment where practical understandings can inform and guide practical judgement (McCormack, 2006).

Health libraries first introduced evidence-based practice to the library and information science field. Definitions of evidence-based practice in the health library context have been provided by Booth and Brice (2004), Crumley and Koufogiannakis (2002), and Eldredge (2000). There are many similarities between these definitions and those that originate from evidence-based medicine. For example, this definition from defines evidence-based practice in librarianship has been defined as:

a means to improve the profession of librarianship by asking questions as well as finding, critically appraising and incorporating research from library science (and other disciplines) into daily practice. It also involves encouraging librarians to conduct high quality qualitative and quantitative research (Crumley and Koufogiannakis, 2002, p. 62)

There is recognition in this definition that evidence can come from qualitative and quantitative sources, as shown by the models and conceptual frameworks for implementing evidence-based practice for library and information services that have been developed by Booth (2007), Booth and Brice (2004), Eldredge (2000) and Watson-Boone (2000). The definitions of evidence-based practice in librarianship may appear to be clear cut, but at this time 'no definition of EBLIP has been proved, nor is there any discussion on how this term relates to or differs from its predecessors' (Thorpe, Partridge and Edwards, 2008, p. 3).

The definition of evidence-based practice in education is less clear. Here, according to Davies (1999) it operates at two levels. The first, similar to the nursing and health care, and library and information sectors, is to use existing evidence from research and literature on education and related subjects. The second is to establish sound evidence where existing evidence is lacking; that is to take a problem-solving, self-directed approach (Davies, 1999). In education, there are signals of a growing acceptance for a multi-faceted approach to evidence-based practice, 'which not only examines the issues related to the research process and organisational culture but also seeks to understand the teacher as a professional learner and information user' (Williams and Coles, 2004, p. 813). A third level, not recognised by Davies (1999), for evidence-based practice in education is for transparent accountability (Dickinson, 2005; Hammersley, 2001) where performance indicators measure whether requirements are being met.

These three levels would seem to be competing forces, but this is an indication that evidence-based practice in education is taking a different direction from that as understood in medicine and health care. The move to use evidence for accountability and performance takes the concept of evidence-based practice a long way from the Sackett et al. (1996), Stetler, Brunell, Giuliano, Morsi, Prince and Newell-Stokes (1998), and Crumley and Koufogiannakis (2002) basic premises that evidence (from a variety of sources) informs practice.

Evidence-based practice in teacher-librarianship has been influenced by the understanding of evidence-based practice in education. This is unsurprising, given that teacher-librarianship is situated in education. However, the definition of evidence-based practice for teacher-librarianship is related more to the purposes for which evidence is used; its purpose revolves around the key question, 'What differences do our school library and its learning initiatives make to student learning?' (Todd, 2002, p. 2). Within teacher-librarianship, Todd suggests that:

evidence-based practice focuses on the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the performance of the day by day role. It is about using research evidence, coupled with professional expertise and reasoning, to implement learning interventions that are effective (Todd, 2002, p. 2).

A more recent statement from Todd suggests that evidence-based practice in school librarianship is about:

professional practice being informed and guided by best available evidence that works, coupled with a focus on evidence of outcomes and impacts of services in relation to the goals of the educational environment in which it is situated. (Todd, 2009, p. 88)

These definitions have some relationship to the previous definitions in this review, where the basic premise is that evidence informs practice. As the primary function of schools is student learning, it is logical that Todd's definitions link the purpose of evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians to student learning. Providing tangible links between teacher-librarian intervention and student learning could be a strong basis to support school library facilities, staffing of professionals and support personnel, and budgets for resources and support services. However, teacher-librarians have multi-faceted roles and definitions of evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians should also consider the professional contributions that teacher-librarians make to the social and cultural aspects of school life as teachers and information specialists. Todd's (2009) definition, for example, seeks to include these aspects. Evidence that encompasses these broader aspects of a teacher-librarian's role could demonstrate the contributions that teacher-librarians make to these aspects of the school. However, at present, evidence-based practice in teacher-librarianship appears to have three aspects: research evidence, locally derived evidence and accountability. While the first two are moderated by professional expertise, the third is systemic, that is required or imposed by employing bodies.

Todd's (2009) discussion paper posits that there are six common beliefs about evidence-based practice in school librarianship, as follows. First, school libraries are essential for addressing curriculum standards. Second, teacher-librarianship is an applied science and profession, which derives its practice from a diverse body of theoretical and empirical knowledge. Thus, teacher-librarians are well placed to lead and transform educational practice. Third, school libraries play a transformative role in the intellectual, social and cultural development of children. Fourth, teacher-librarians enable the transformation of information to knowledge through their teaching programmes. Fifth, the value of a school library can be measured, in terms of documented transformations of learning outcomes, and personal and social growth of the students. Sixth, sustainable development is associated with accountability for meeting espoused goals. These beliefs (Todd, 2009, p. 91) move evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians from a rhetorical warrant to an evidential warrant for professional practice; from a persuasive or advocacy framework to a declarative and demonstrable framework; from a process framework to an outcomes framework; and from a tell me framework to a show me framework.

Todd's thinking opens the conversation for a new direction for evidence-based practice in teacher-librarianship. Likewise, there are implications for education. The six core beliefs identify a purpose for evidence-based practice in teacher-librarianship that goes beyond accessing, appraising and utilising research to solve problems and inform practice. There is a basic premise in evidence-based practice generally, that evidence informs practice, but beyond that there appear to be competing and at times conflicting ideas about what evidence-based practice is and how it should be used. For teacher-librarians there is a greater emphasis on accountability to use evidence-based practice to demonstrate impact on student learning, where the practice is embedded in professional practice. This was an aspect which required further investigation and leads to the aim of this research.

Research about how practitioners understand evidence-based practice

Research about how practitioners in library and information services, and teacher-librarianship in particular, understand evidence-based practice is limited. A study by Partridge, Thorpe, Edwards and Hallam (2007) identified a need to understand how library and information services professionals experience and understand evidence-based practice. 'If the LIS profession is to evolve into one grounded in EBP then we need to take stock of what the profession currently understands of practitioner's [sic] experiences of EBP in the context of their professional practice' (Partridge, Thorpe, Edwards and Hallam, 2007, p. 10). Partridge, Edwards and Thorpe (2010) subsequently conducted a phenomenographic study with library and information services professionals that involved semi-structured interviews.

The result was a model to describe the collective experience of evidence-based practice for library and information services professionals as presented in Table 1:

| Categories of evidence-based practice | Focus of evidence-based practice |

|---|---|

| Evidence-based practice is experienced and not relevant | Evidence-based practice is a professional accident. It happens by default because I am a library professional. |

| Evidence-based practice is experienced as learning from published research | Evidence-based practice is learning from and using research. |

| Evidence-based practice is experienced as service improvement | I undertake evidence-based practice to improve what I do or what my library and information service offers. |

| Evidence-based practice is experienced as a way of being | Evidence-based practice is an integral part of my job. My job is evidence-based practice. |

| Evidence-based practice is experienced as a weapon | I am forced to use evidence-based practice when I am pushed into a corner. |

This research found that the range of approaches that the practitioners applied to evidence-based practice 'do not necessarily resemble the existing models of EBP inherited from the health and medical domains' (Thorpe, Partridge and Edwards, 2008, p. 11). Moreover, it established that evidence-based practice is an experience, not a process.

Research using a grounded theory methodology conducted by Koufogiannakis (2013) explored how academic librarians used evidence in their professional decision making. Traditionally, evidence-based practice has focused on decision making and this research was able to provide deeper understanding of this. The theoretical concept of convincing was determined as the main way that academic librarians used evidence. Koufogiannakis (2013) gained insights into how the current evidence-based practice in librarianship model may need to change as academic librarians used a multitude of evidence sources and these depended on the situation or context and the decision to be made.

These research studies (Partridge, et al., 2007; Partridge, et al., 2010; Koufogiannakis, 2013) investigated the lived experiences of library professionals. Hunsucker considers that understanding the 'consequences of the quality of our practice... through the lived world of their users' (2007, p. 28) leads to an expanded and broader view of evidence-based practice (2007, p. 2). It indicates that evidence-based practice has evolved and is now very different to that which was first conceived by Sackett et al. (1996) and its subsequent hierarchical and procedural models for implementation. It is notable that Booth (2010a), an original exponent of evidence-based practice, now recommends 'ditching the premise' of evidence hierarchies such as those used in the models developed by Booth (2007, p.84) and Eldredge (2006) and now considers that there 'is no single authoritative hierarchy of evidence'. Hjorland (2011), in recognising the links between evidence-based practice and its one-sided hierarchical approach, suggests that it may be better instead to speak of research based practice, thus allowing a broader interpretation of the concept. In this way, by suggesting a new terminology, a broader understanding of evidence may evolve.

Research design

This study was designed to address the research question: How do teacher-librarians perceive and use evidence-based practice? The research design was informed by constructionist philosophy and interpretativist perspective, whereas expanded critical incident technique governed the methods for data gathering and analysis. McKenzie considers that 'Constructionism… sees knowledge as dialogically constructed through discourse and conversation rather than produced within individual minds' (2003, p. 262). Interpretativism focuses on understanding and meaning making as opposed to explanation. In interpretative research, meaning is disclosed, discovered and experienced (Himika, 2008). Meaning is something we make or construct, not something we find or discover (Smith, 2008).

Meaning making is the primary goal of interpretative research and allows narrative to tell the story. The researcher is not detached from the inquiry, allowing for reflexivity on the part of the researcher.

This research explored the lived experiences of teacher-librarians as evidence-based practitioners. A lived experience could be described as a personal worldview where teacher-librarians in this study described incidents in context about their evidence-based practices. As these incidents were described, teacher-librarians became self-reflective about their actions and circumstances. Their experiences are the evidence, or the truth for the moment, about the incidents. Parse (2008, p. 47) describes 'truth for the moment' as giving voice to an individual's personal wisdom. Lived experiences are not the truth; they are valuable accounts that expose understandings, reflections, assumptions and perspectives about events (or incidents) and circumstances (Geeland and Tayor, 2001).

Flanagan (1954) developed critical incident technique as an approach to identify effective and ineffective behaviour relating to a particular activity. Critical incident technique encourages participants to recall critical incidents or significant instances when they were involved in a particular activity. The expanded critical incident approach is a related approach, developed by Hughes (2012) which investigates the real-life experiences of a select group of participants, through semi-structured interviews and inductive data analysis. The expanded critical incident approach has five phases of planning, collection, interpretation, analysis and reflection.

The expanded critical incident approach is well suited to exploratory research. This is the first time that the expanded critical incident approach has been used to explore teacher-librarians and evidence-based practice (Gillespie, 2013). Other methods allow for semi-structured interviews, but in using the expanded critical incident approach I could concentrate the questions upon critical incidents. As a researcher, I began with the assumption that there was discreet knowledge or experience that each participant possessed. In drawing out the participants lived experiences of evidence-based practice they could relate an incident, provide an example of its use and their response or action following.

For this study, I designated critical incidents to be instances when a teacher-librarian used evidence in some way to inform and guide their practice as a teacher-librarian. Critical incidents could be described as memorable and meaningful events. Examples of critical incidents could be when a teacher-librarian observes students using resources for study-related purposes; a teacher-librarian reads a scholarly article or report; a teacher-librarian gains formal and informal feedback provided by the principal, teachers, students or parents. These events may seem to be part of normal routine. What makes them critical in terms of this research is that they caused a response from teacher-librarians. The response may have been a reflection, or a raised awareness that the event was something to take note of and act upon. I sought to gain further understanding about how teacher-librarians worked to improve practice and what types of evidence they valued or responded to or informed their practice.

The findings, which integrate the participants' reported actions, thoughts and feelings, create a holistic picture of teacher-librarians' experiences of using evidence in their professional practice.

The participants and data gathering

During 2009 and 2010, fifteen qualified teacher-librarians currently working in Australian schools were interviewed for this research. The participants came from primary, secondary and multi-campus schools in major cities and regional areas. The recruitment related to convenience and used snowball sampling (Flick, 2006; Patton, 2002). In applying the expanded critical incident approach, I used a variety of strategies to gather data, allowing for triangulation of data (Denzin and Lincoln, 2008; Flick, 2006). Data collection relied on face-to-face interviews conducted, when possible, in the interviewee's workplace. Additional strategies including on-site observations, journaling and the rubric (Henri, Hay and Oberg, 2002) for contextual information, verified the emerging interpretations of the data (Gillespie, 2013). In particular, these approaches allowed each of the interviewees to tell their own story and enriched the data.

Data analysis

The purpose of the analysis was to uncover aspects of teacher-librarians' experiences of evidence-based practice and to identify what they considered to be evidence. All interviews were exposed to many sessions of analysis. Similar to the expanded critical incident approach, the analysis involved two types of data categorisation: binary and thematic. Binary classification, which is typical of the critical incident technique (Flanagan, 1954), was used to identify factual details, for instance, whether the outcome of the incident was positive or negative. Thematic analysis (Ezzy, 2002; Saldana, 2009) involved categorising the emerging themes. This analysis phase, which was concerned with data reduction, reminded me of taking a crop of tomatoes and reducing and reducing the fruit until you are left with tomato paste. Similarly, the analysis process refines the essence of the data until it is condensed, thick and rich. The terms and categories of the analysis framework emerged inductively through gradual sifting and refining of the data.

In responding to the interview questions, the answers from the interviewees provided descriptions of their activities, interpretation, opinion and feelings all mixed in together. The responses to the interview questions represented the teacher-librarians' total experience or their experiential knowledge, termed 'thick description' (Geertz, 1973). I developed an analysis framework which allowed me to capture and sort each of these aspects so that I was able to analyse, condense and finally describe the total experiences of the teacher-librarians as evidence-based practitioners (Gillespie, 2013).

Limitations

Research is not without limitations. It could be argued that confining this research to the perspectives of Australian teacher-librarians could be a limiting factor. However, it is more common in Australia that professional teacher-librarians have dual qualifications in education and librarianship. While the title and educational models for teacher-librarians may differ in other countries, there is potential that these findings can be utilised outside Australia and go beyond the profession of teacher-librarianship to further develop evidence-based practice in education and the library and information sciences.

The findings

The findings from this research present a research based perspective of the experiences of teacher-librarians as evidence-based practitioners as a model and critical findings. This paper focuses on the overarching critical finding and a supporting critical finding.

- Overarching critical finding: evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians is a holistic experience.

- Supporting critical finding: evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians involves both purposefully engaging with evidence and accidentally encountering evidence.

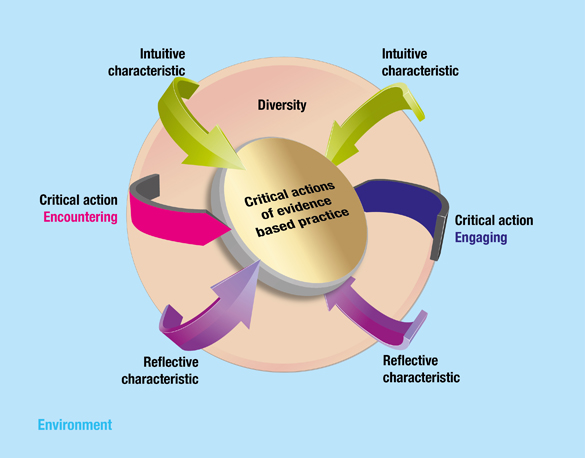

The empirical model that underpins the critical findings will now be described. The model (Figure 1) represents the total experience of evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians. The model has three layers: the inner circle contains critical actions, which represent the core activity of gathering and using evidence; the outer circle contains diversity, which represents the human dimensions of the activity; and the surrounding rectangle represents the environment in which teacher-librarians operate as evidence-based practitioners. Thus the model shows that critical actions are at the centre of evidence-based practice. Critical actions are the ways in which teacher-librarians gather and use evidence. These actions are of two kinds: engaging and encountering. Engaging involves purposeful evidence gathering, while encountering involves unintended evidence gathering. Significantly, as the model shows, engaging and encountering are like two sides of a coin; they are inextricably linked and either one side or the other always faces outward. The critical actions relate to critical incidents. They represent the ways in which teacher-librarians act as evidence-based practitioners. The arrows represent the critical characteristics of the nature of teacher-librarians' actions as evidence-based practitioners. These characteristics are reflective and intuitive. They are associated with both types of critical actions, and so are shown on either side of the central coin.

Diversity and environment are the influencing aspects of evidence-based practice. Diversity reflects the environment in which teacher-librarians work. Diversity encompasses many aspects of evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians; including the school communities in which they work, their role descriptions, their needs and uses for gathering and using evidence; and in the ways in which they approached gathering and using evidence.

There are several possible alternative terms for environment, such as, setting, situation and information world (Courtright, 2007). It could also be described as the context. For this research I adopted the term environment to describe the workplace, the people and the circumstances in which the teacher-librarians operate and where the critical incidents occurred.

There is an evident distinction between actions and approaches. Actions are what teacher-librarians do in carrying out their roles and are either purposeful (engaging) or unintended (encountering), whereas approaches represent the how and what of teacher-librarians' evidence gathering practices. Approaches could include interviewing students, listening to a speaker at a conference, collecting student borrowing statistics. Approaches are characterised by diversity and like actions they can involve both engaging and encountering. The empirical model (Figure 1) is a graphical representation of the holistic nature of evidence-based practice as expressed in the overarching critical finding.

The critical actions and critical characteristics of evidence-based practice at the centre of the model do not operate in isolation; they are intermingled and entwined. Clarifying each of these actions and characteristics is like teasing out a tangled ball of wool as each one does not stand on its own; however, for each incident that the participants of this research described, one action and characteristic is more prominent than the others. I will now focus attention on two individual aspects that comprise the empirical model, that of engaging and encountering. The focus of this paper will make the links between these two actions represented in the model with the overarching critical finding and the supporting critical finding.

The critical actions of engaging and encountering

The findings indicate two overarching actions that describe how teacher-librarians experience evidence-based practice. These actions are:

- engaging: a deliberate and purposeful activity, and

- encountering: an unintended or serendipitous activity or event.

Incidents involving both purposeful engagement and accidental encountering of evidence have been examined in this study, and can be described as:

- engaging having two modes, that of purposeful seeking and purposeful scanning, and

- encountering also having two modes, that of accidental finding and accidental receiving.

Zooming in on the critical actions that represent the two sides of the coin, Table 2 demonstrates the relationship of the critical actions to the whole model. It provides a detailed representation of how teacher-librarians act as evidence-based practitioners and explains the ways in which teacher-librarians engage with and encounter evidence.

In Table 2, the first column identifies the type of critical action, whether engaging or encountering. The second column shows the two modes for each of the critical actions. The third column outlines the intention associated with each critical action. The fourth column, entitled Activity, describes the nature of the critical action and how teacher-librarians could engage with or encounter evidence. The fifth column presents examples of real actions described by teacher-librarians during interviews. The critical actions and activities are all encompassed by the influencing aspects of diversity (represented by the inner border) and environment (represented by the outer border).

| teacher-librarians' environment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diversity | Critical actions | Intention | Activity | Example | |

| Engaging | Purposeful seeking | teacher-librarian is actively seeking contact with an identified source and is searching for specific evidence | teacher-librarian asking pre-planned questions; using active questioning strategies | teacher-librarian initiates surveys, uses formal feedback mechanisms and/or conducts direct interviews | |

| Purposeful scanning | teacher-librarian identifying a likely evidence source to provide evidence for a specific purpose | teacher-librarian identifying an opportunity to ask a question; actively listening or observing within or outside the school environment | teacher-librarian is actively listening, observing and/or recording; taking photos to record events; collecting student work samples; attending a conference or workshop; participating in a listserve, network group, online discussion | ||

| Encountering | Accidental finding | teacher-librarian serendipitously encounters evidence in unexpected places | teacher-librarian receiving feedback that he/she overhears or observes in unexpected settings | teacher-librarian gains unsolicited evidence through overheard comments, emails, chatting with students, teachers, parents | |

| Accidental receiving | teacher-librarian receives unexpected feedback as evidence sourced by another party | teacher-librarian receiving evidence through another source as a third party or by proxy | Principal receives feedback from other sources and in conversation passes this to the teacher-librarian. Principal instigates his/her own investigation and provides this to the teacher-librarian | ||

As the empirical model and this detailed critical actions table show, for teacher-librarians evidence-based practice is not a series of steps or procedures to be followed; it is a simultaneous, fluid movement that can involve encountering evidence, reflection, engaging with evidence and improving practice. A supporting critical finding emerging from this research shows that evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians involves both purposefully engaging with evidence and accidentally encountering evidence.

To begin the description of these aspects, the next section will provide examples to explain how teacher-librarians engage with and encounter evidence to highlight the intent and activities of teacher-librarians as they gather and use evidence. Although I begin with the critical action of engaging with evidence, these actions are not presented hierarchically, nor is one favoured over the other.

The critical action of engaging with evidence

Engaging with evidence has two modes, that of purposeful seeking and purposeful scanning. Purposeful seeking is an action where a teacher-librarian is actively seeking contact with an identified source and is searching for specific evidence; whereas purposeful scanning involves a teacher-librarian identifying a likely evidence source to provide evidence for a specific purpose. Each will be described below, using direct quotes and vignettes to illustrate specific incidents that teacher-librarians related in this research. Each teacher-librarian is identified by a pseudonym to protect their identity.

Engaging with evidence - purposeful seeking

Caitlin purposefully sought evidence when she interviewed one-on-one the senior students to gain their reactions to the new online databases that had been introduced and the hands-on training that they had received. She recorded the actual statements of the students, which she describes as 'real evidence… and it adds a different dimension, you know it is voices that come in… it just gives you credibility, I think'. The intent of Caitlin's evidence-seeking was to gain feedback from the students. She had a specific purpose, hence she was purposefully seeking evidence to evaluate the new online databases which had been introduced. The activity of this targeted investigation was Caitlin's asking the students pre-planned questions. She was able to collate their responses and make adjustments to how the students were introduced to the databases in the future. The feedback evidence provided information for the teaching team to evaluate and then re-structure their approach for the students in the following year.

Engaging with evidence – purposeful scanning

The following vignette illustrates how Meg's deliberate engagement with evidence informed her decision making. Meg engaged with, or purposefully scanned for evidence when she took a collaborative approach to evidence gathering in setting up a library staff wiki. Her intention in using the wiki was for a specific purpose, in that the evidence gained from the wiki could inform decision-making and demonstrate the library's accountability.

Meg supervises a library staff of 22, so she is very heavily involved in school library management. She is concerned with the provision of access to information for the students but also for her own staff. Meg likes to keep the school library at the forefront of technology and innovation, but everything needs the approval of the school management. While the school management is generous with the library budget, when moving for change she first needs to present a convincing case to them. It is here that evidence is necessary to support her case for any changes – whether these be in approaches to teaching, staffing or tools for learning. Meg reflects that: 'evidence actually assists you to go to management and say, as a team, not just me, we think this is a great idea… we would like to do this because…'

Meg's approach had additional benefits. Her collaborative approach to evidence gathering empowered her staff by actively involving them in the process. Meg wanted each staff member to have some sort of commitment from a professional point of view, thinking about how they could make a difference. To this end, she encouraged the staff to report in a wiki the things that they were doing differently over the year. The wiki gathered actions, thoughts and fresh ideas from everyone, even those who may not normally contribute. In this way the staff who may have felt less empowered could see that they too have made an impact.

To Meg, the staff comments in the wiki constitute important evidence. Her collaborative approach to evidence-based practice has the benefit of building strong team relationships, by providing an opportunity for new ideas to be shared. By gathering and documenting evidence in these ways Meg is engaging by purposefully scanning for evidence.

Many participants experienced purposeful seeking and scanning as they engaged with evidence. Caitlin and Meg have been highlighted as two examples in Table 3. It is now possible to expand on Table 2 Critical actions in the empirical model to provide a fuller description of engaging with evidence.

| Critical actions | Intention | Activities | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engaging | Purposeful seeking (Caitlin) |

Active seeking of evidence to gain feedback from the students, with a specific purpose to evaluate the new online databases that had been introduced. | Asking students preplanned questions. Collating responses for evaluation and to guide future planning and teaching. |

Student feedback, via interviews taken one-on-one, was recorded. |

| Purposeful scanning

(Meg) |

Identify the wiki as a likely evidence source to provide evidence specifically to empower staff by gathering thoughts and actions of staff and record the library's activities. | Using the wiki as an opportunity to collate staff responses and ideas. | Active participation of staff using the wiki; recording of events; recording of ideas and actions. | |

In these examples from Caitlin and Meg, evidence is recorded in some way. These are deliberately planned activities. Purposeful seeking is the more structured approach with a more clearly defined purpose of searching for evidence to meet a particular pre-defined need. Purposeful scanning, also a deliberate activity, is less structured. Both activities could provide evidence that is unexpected, but in the less structured approach of purposeful scanning, unexpected evidence is more likely. This could provide insights and opportunities that were not anticipated when the activity was first planned. This is not a hierarchical representation; the activity that has been undertaken by Caitlin or Meg in these instances has been governed by their evidence needs and the environments in which they work.

Implications for teacher-librarians

As Meg and Caitlin's examples show, engaging involves teacher-librarians in deliberately planning and seeking evidence for specific needs identified by them. There is much evidence available within the local context that teacher-librarians can draw upon, and like Caitlin and Meg they can put strategies in place to capture the local data. These strategies involve forward thinking to plan the purpose of the evidence gathering, recognising the evidence available to them and then devising a process to easily record it. While the examples provided here from Meg and Caitlin have involved gathering evidence from the local context, deliberate engagement with evidence could also involve gaining evidence from external sources, for example, by purposefully seeking benchmark data to align the school library collection with national standards, or purposefully scanning for specific information by attending a session at a conference. These examples indicate that teacher-librarians can plan and deliberately seek evidence to meet specific and pre-determined needs and then devise a strategy to capture that evidence. However, not all evidence seeking by teacher-librarians is a deliberate pre-planned activity. The opposite side of the critical actions coin, the critical action of encountering evidence, will now be described.

The critical action of encountering evidence

Encountering evidence has two modes, that of accidental finding and accidental receiving. Accidental finding is a serendipitous encountering of evidence, usually in unexpected places, whereas accidentally receiving evidence is sourcing evidence from another party.

Encountering evidence – accidental finding

The following examples from Caitlin and Donna (Table 4) illustrate ways of encountering by accidentally or unintentionally finding evidence. The following vignette describes how Caitlin encounters, or accidentally gains, evidence affirming that teaching interactions have been successful.

Caitlin reported being 'quite chuffed' one day when she was working in the library and a Year 8 boy came up to her after school and said, 'You know that site that you were promoting on the library blog; well it is blocked at school'. She replied, 'Oh OK, that is really good feedback. I didn't realise that'. Since she had not promoted the blog much, she asked the student how he knew about it. He replied, 'Oh I put an RSS feed on it'. Caitlin thought 'Whoo hoo!' because this was evidence that the students are competent users of the library blog and it was affirmation that the students were using Web 2.0 tools in a positive way to enhance their learning. This incident also led her to reflect that in future she should cover more advanced Web 2.0 strategies, such as using RSS feeds with Year 8 students.

Caitlin's encountering of this evidence is completely unexpected, but very opportune. Although she had constructed the blog and promoted it with the students, she had not structured any devices to gather evidence of its effectiveness or use. The activity described here involves the unsolicited feedback from a student, which indicated that the student was not only using the blog, but had put mechanisms in place by way of an RSS feed, so that he could easily retrieve it in the future. It was also an indication that the skill set of this particular student, and possibly others in his cohort, was well developed to take the students further in the future. As a further example, the following vignette indicates how Donna used evidence she accidentally found, gained by chance from students:

Donna comments, 'Feedback from the boys is probably as important as anything to me'. She describes a teaching moment when a student made a comment, 'Now I can see…' that indicates to her that he had understood a particular point, leading her to think 'Oh my god, he's got it, he's nailed exactly what we are doing in here, why we are doing this research, working through this process'. This is evidence about him transferring his skills from what he had learnt previously to a new learning focus and causing him to say 'Now I can see how to do this'.

Again, this evidence from the student was completely unexpected but provided an opportunity for Donna to understand how the students were developing as inquiring learners. This was a serendipitous and unstructured activity that provided Donna with valuable feedback.

For Caitlin and Donna, the evidence gained from the students was unstructured, unexpected and not recorded, yet provided valuable feedback for Donna on her teaching activities and for Caitlin on the way in which she was facilitating access to information. In these two examples the feedback evidence had been positive but it could just as equally have been negative. No matter what the feedback, the evidence gained from chance encounters is something that teacher-librarians can use to inform practice and guide future decision-making.

Encountering evidence – accidental receiving

Accidental receiving of evidence is understood as sourcing evidence from another party. For example, a teacher-librarian is told some information or feedback, usually during a personal encounter. In this case, encountering evidence is unexpected and unsolicited and could be described as coming out of the blue. As illustrated by the following vignette, Caitlin experienced such an encounter, when she accidentally received evidence during a conversation with her Head Master.

Caitlin was actively gathering evidence and documentation for her yearly teacher appraisal. She sought clarification and began talking the process over with the Head Master where in conversation he asked her, 'How do you think your year has been?' to which Caitlin replied that it had been a big year and she thought that she had achieved a lot. His reply, 'My word you have', was unexpected especially as she had not yet submitted her appraisal document.

With this comment, the Head Master unexpectedly provided affirming evidence that Caitlin was performing well in her professional role. The Head Master had already come to some conclusions about how the library had impacted on teaching and learning at the school and in an encountered conversation passed his thoughts onto Caitlin. While Caitlin had not sought this evidence from a third party, it affirmed her activities.

In light of these highlighted examples it is now possible to expand on Table 2 Critical actions in the empirical model to provide a fuller description of encountering evidence.

| Critical actions | Intention | Activities | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Encountering | Accidental finding (Caitlin, Donna) |

Serendipitous encountering of evidence in unexpected places | Finding unexpected and unsolicited feedback from students. These can be overheard, or directed to a teacher-librarian | Chance comments from students |

| Accidental receiving (Caitlin) |

Unexpected evidence sourced from another person in a chance encounter | A teacher-librarian being told something which has been sourced by another person. Chance comments and/or encounter | The Head Master relays in a chance conversation, his own conclusions about the activities of the library | |

In these examples of encountering evidence, nothing is recorded initially. It is noted mentally by the teacher-librarians and remembered as an anecdote. However, this encountered evidence could be recorded in some way, thus preserving this evidence as a source for evaluation of their activities. In such encounters, the evidence has not been deliberately sourced to meet any particular need and may indeed reveal inadequacies and areas that could be improved, thus providing opportunities and insights that had not been anticipated. It was pleasing for both Caitlin and Donna that their activities produced such positive responses. Again this is not a hierarchical representation, and the encountered evidence is as a result of their activities in their workplace environments.

Implications for teacher-librarians

As shown by the above examples, teacher-librarians might experience encountering as an unintentional or serendipitous activity or event. If alert to evidence, they might receive useful feedback in the form of an overheard remark or unexpected observation, or an accidental receiving, through a third party. They might benefit from encountering evidence that is not pre-planned, nor with a specific pre-defined purpose in mind. Encountered evidence, as illustrated here, can be sourced in the local environment of their library or school. It is worth noting that encountered evidence also has the potential to expose weaknesses that need to be addressed. Mostly, encountered evidence is not recorded and the teacher-librarian may just remember it as an interesting anecdote. Other times, encountered evidence strikes a chord, causing the teacher-librarian to think that this is something that could be useful in the future. This is not systematic and is most likely only to be recorded in some way if the encountered evidence relates in some way to needs that have already been identified.

Encountered evidence may also be sourced externally, for example, when attending a workshop where the speaker provides information causing teacher-librarians to think of new possibilities for their own situation. This may be recorded in an informal way as notes at the time of the workshop attendance, should teacher-librarians recognise at the time that the unexpected information is meeting an identified need. This type of evidence is more likely to be recalled when the situation arises at a later time.

As explained, engagement with and encountering of evidence are not hierarchical structures; they are also not static. The incidents described here were chosen to demonstrate one critical action at a time, yet many of the incidents described by the teacher-librarians demonstrated a dynamic and fluid relationship between the two critical actions, as the next section will show.

Working together: encountering and engaging as a fluid approach

The shorter examples presented so far tend to obscure the complexity and fluid nature of evidence gathering and use as experienced by teacher-librarians. The research revealed many incidents that demonstrated a seamless, fluid movement from one action to another as teacher-librarians experience evidence-based practice. The following vignette of Joan is an example of a teacher-librarian moving from engaging by actively seeking evidence, then scanning for supporting evidence, to finally accidentally receiving, from a third party, affirmation that her practices had been successful.

On Joan's appointment to her school she wanted to change the way that the teacher-librarian interacts with the students. The previous teacher-librarian had provided RFF (relief from face-to-face teaching) and had little contact with teachers to plan and no opportunity to work with the class teacher as a teaching team.

Joan's current agenda is to improve the quality of teaching. She approaches her principal and he agrees to a trial of cooperative planning and teaching with a flexible timetable. In order to gather evidence to support her case, at the end of the first term Joan engages by purposefully seeking evidence from the teachers using written surveys where she asks questions such as, 'What were the benefits for the students? What were the benefits of working professionally in a team? What improvements could be made? Would they be prepared to do cooperative planning and teaching in the future?'

With further engagement, Joan purposefully scans for further evidence to support the evidence she has gathered from the teachers. She collates a table where she plots the teachers she has worked with, the classes she has taught, the number of hours involved. She plots the skills that have been covered against the education department's information skills outline and the results that the students achieved. She is able to present this evidence at a staff meeting to gain support for the co-operative planning and teaching programme (CPT) to be continued.

Joan presents all of the evidence she has gathered to the principal and she finds that without seeing her evidence, the principal has already formed an opinion. He says:

Joan, there's no need for me to even look at that [and] If we go back to RFF there will be a staff mutiny. You've converted the library into the hub of the school more quickly than I ever thought you would. CPT is here to stay.

Joan encountered confirming evidence when she accidentally received evidence from a third party (her principal) as affirmation that her introduction and implementation of cooperative planning and teaching has been successful.

While only one of the critical actions of engaging or encountering evidence was prominent at any time, as this vignette demonstrates, Joan moved seamlessly and perhaps without realising it herself from the actions of purposeful seeking using the written surveys, to purposeful scanning where she collated and plotted students' skills, to move to accidentally receiving evidence from her principal. Joan described this as one incident, yet it demonstrates a flexible, holistic approach as she completes an evidence picture that affirms the successful implementation of her cooperative planning and teaching activities.

From the example provided by Joan, it is now possible to expand on Table 2 Critical actions in the empirical model to provide a fuller description of the fluid movement between engaging and encountering evidence.

| Critical actions | Intention | Activities | Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engaging | Purposeful seeking (Joan) |

Active seeking of evidence to gain feedback from the students, with a specific purpose to evaluate the new approach to teaching and learning | Seeking written survey responses from teachers | Written surveys |

| Purposeful scanning (Joan) |

Joan collates a table where she plots the teachers she has worked with, the classes she has taught, the number of hours involved. Joan plots the skills that have been covered against the education department's information skills outline and the results that the students achieved |

Collating spreadsheets and tables of class times, activities Plotting students' information skills against education department skills outline |

Spreadsheets Collated and plotted students' information skills |

|

| Encountering | Accidental receiving (Joan) |

Unexpected evidence sourced from another person in a chance encounter | A teacher-librarian being told something which has been sourced by another person. Chance comments and/or encounter | The Principal unexpectedly relays his own conclusions about the new approach the teacher-librarian has taken to teaching and learning |

Implications for teacher-librarians

While engaging and encountering cannot occur simultaneously, they can however follow each other, with the coin constantly flipping between one side and the other. This is the fluid approach that teacher-librarians use when they find evidence using one action, for instance deliberate engagement, and then being aware of supporting evidence, perhaps from accidental receiving, as the example from Joan above indicates.

Engaging and encountering are terms I have applied to describe the critical actions of evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians. However, in practice, the research suggests that teacher-librarians do not consciously make the same distinction. The incidents revealed a fluid movement between the two critical actions as teacher-librarians sought and gathered evidence to meet predetermined needs where they engaged with evidence or they serendipitously came upon or encountered evidence. This demonstrates that for teacher-librarians, evidence-based practice can be guided by professional knowledge and expertise. There can be a seamless movement from one action to the other as a teacher-librarian as a practitioner draws on her professional knowledge and experience, gains affirmation through the evidence received and then moves to the next activity. The example from Joan illustrates the fluid nature of evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians, but it also highlights how a teacher-librarian can draw on her professional knowledge and experience to initiate a new approach to teaching and learning and then to gather and use evidence to support her actions.

Discussion

Engaging with and encountering evidence are at the heart of evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians. This is described in the following supporting critical finding.

evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians involves both purposefully engaging with evidence and accidentally encountering evidence.

The critical incidents described in this research indicate a higher prevalence of approaches that were informal and non-specific, and this could be related to time pressures to gather and record evidence, a lack of knowledge and skills to devise and assemble evidence, and a sense that they were trying to measure unrealistic outcomes (Todd, 2003). For example, Andy, who I interviewed as he attended his first international conference, was perhaps the least professionally experienced teacher-librarian who participated in this research. He had a sense of what he needed to do to improve the library facilities and the way that it interacted with the school community but he struggled to make sense of how he could be evidence-based in his practice. Here Andy describes his dilemma:

I don't know if I can measure it, I don't know if I am even measuring the right thing. By all the standards that come out of the books I may be a dismal failure. I don't care, but there are plenty of kids and plenty of parents who reckon that I am doing a reasonable job, and I can deal with that. Fine, OK. That kid now picks up books and they share them with their family. And we win.

Todd (2003) suggests that more formal evidence-based approaches can reveal richer and more precise statements of outcomes, enabling a more clear articulation of benefits. Contrasting Andy's dilemma is the approach taken by Joelle. She was able to evaluate her own performance using evidence-gathering tools after enrolling in an online course targeted at librarians to develop skills in the use of quantitative and qualitative research, and how to use data, statistics, circulation details, student borrowing and library use activity. Joelle also attended a workshop that focused on lifting the presentation of the library. She gathered evidence about what resources were needed by working with teachers on assignment topics so that she could ensure that the library would be able to provide the print and online resources, and then she ran professional development for the staff on the use of databases. Joelle documented these activities and by providing supporting statistical evidence she was able to build a report for the school board to advocate for the library and its resources. As a result of these evidence-based practices and with the support of the school board, she was able to make many improvements to the ways that the students access information both on and off campus.

Among teacher-librarians there appears to be an increasing acceptance of evidence that can be derived from a variety of sources. There is an opportunity here to align this more open view of evidence with specific outcomes that relate to the local environment. Within the profession, this is a strategy that, when awareness is raised, has potential for improving evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians.

There were instances where teacher-librarians, on encountering experiences and observations, used their professional knowledge and experience to build an evidence base in which they actively engaged with evidence. In moving from encountered evidence to an engagement with evidence, teacher-librarians were able to provide creditable measures of success. In doing so, advocacy for change moves from self-interest, to advocacy with evidence to address real and identifiable needs to align the library with the learning needs of the school. It was in these instances that evidence could be used to gain support from school administrators such as the incident already described when Joan used evidence to gain the principal's support for introducing cooperative planning and teaching. Joan moved beyond advocacy when she was able to gain further support from the principal, when he confirmed that her cooperative approach to teaching should continue. Although the principal could see that the changes had been successful, Joan was able to provide supporting evidence of the skills the students had learned when she plotted them against the education department's information skills outline. She was able to provide real evidence on how the teaching approach was having a positive impact on student learning.

Evidence can include work samples, a remark from the principal, feedback from teachers, observations made of or by students, borrowing statistics, benchmarks from local and reliable external sources, and personal reflection. The teacher-librarians in this study had much evidence that they could draw upon to demonstrate their impact on all aspects of their involvement in the school community to guide their decision-making and gain understandings of their own practice.

This aligns with Boyce (2008), who considers that the fundamental principles of evidence-based practice can be seen in the day-to-day practice of teacher-librarians. The examples, vignettes and illustrations of practice highlighted in this research confirm the assertions of Todd (2002) and Boyce (2008). However, many of the critical incidents in this research revealed an encountering of evidence, with a reliance on observation, anecdote and chance encounter and coincides with a lack of specificity and precision (Todd, 2003). teacher-librarians were aware of what they wanted to achieve, but were unsure about how to articulate and specify these as outcomes.

The implication is that teacher-librarians need to better recognise the value of these various types of evidence and apply them, in order to build an evidence base that demonstrates their contributions to the academic, social and cultural aspects of the school. However, many of the participants showed a lack of awareness of encountered evidence and its possible uses in their evidence-based practice, indicating that for teacher-librarians evidence-based practice is an emerging and under-developed practice.

The way forward

The empirical model emerging from this research opens the door for new thinking about evidence-based practice. Although teacher-librarians were the focus of this study, the findings are not necessarily restricted to this sector. teacher-librarians are teachers and library and information professionals, and there is much from the empirical model that can be utilised within the information and education professions.

Through reviewing the literature in this area, I can conclude that no other researchers or practitioners describe evidence-based practice as holistic in nature. The most closely aligned finding comes from Partridge, Edwards and Thorpe (2010), who describe evidence-based practice as an experience rather than a process. Whilst many of the critical incidents described by participants did not involve an explicit engagement with evidence gathering and use, they did exhibit a professional maturity in the ways in which their evidence gathering occurred. They were continually building their professional knowledge, not through formal research, but by utilising networking opportunities and exposure to new ideas at conferences and workshops. These are not formal channels or mechanical processes.

To spread the message about evidence-based practice among teacher-librarians will involve tapping into teacher-librarians' preferred ways of gaining professional knowledge. This could be likened to creating the ripple in the pond, where teacher-librarian practitioners spread success stories to first raise awareness and then, as interest levels and motivation peak, build professional capacity in workshops and conferences. Less formal approaches could include blog postings and listserve comments, which could be followed up with journal articles specific to teacher-librarians. The ripple in the pond approach, however, tends to keep this valuable information contained within the profession and there is a need to advocate the power of evidence among the broader education and information sector.

Conclusion

This article has presented findings about the holistic nature of evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians and represented this whole experience in an empirical model (Figure 1). It has revealed that, in this context, evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians is centred upon the critical actions of engaging and encountering. While these two actions cannot occur simultaneously, they can however follow each other, with the coin constantly flipping between one and the other. This demonstrates the fluid approach that teacher-librarians use when they find evidence using one action, for instance deliberate engagement, and then being aware of additional evidence, perhaps by accidentally receiving it, are able to provide further supporting evidence of their actions. The featured examples and vignettes which have highlighted each of these actions of engaging and encountering, demonstrate that these actions do not operate in isolation; they are intermingled and entwined. They contribute to a picture of teacher-librarians' experiences of evidence-based practice. When viewed together, they reveal that evidence-based practice can be simple or complex and that evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians is not a linear, step-by-step process. It is beyond this article to present the complete picture of evidence-based practice for teacher-librarians. The remaining parts of the model add further dimensions of evidence-based practice, they give depth and meaning to the model as a whole and can be explored at another time.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the teacher-librarians who gave their time and made valuable contributions to this research.

About the author

Ann Gillespie, PhD, is a postdoctoral research fellow in the Information Studies Group of Queensland University of Technology in Brisbane, Australia. Her work as a teacher-librarian in primary schools led her to investigate evidence-based practice within that context. Her current research explores evidence-based practice as it is experienced in the public libraries. She can be contacted at: am.gillespie@qut.edu.au. Her earlier papers are at http://eprints.qut.edu.au/view/person/Gillespie,_Ann.html