The impact of organizational information culture on information use outcomes in policing: an exploratory study

Douglas Edward Abrahamson and Jane Goodman-Delahunty

Australian Graduate School of Policing and Security, Charles Sturt University, P. O. Box 168 Manly, 1655 New South Wales, Australia

Introduction

North American policing policies and practices continue to shift under the weight of competing administrative, programmatic, strategic, and technological priorities (Braga and Weisburd 2007; Murphy and McKenna 2007; Tilley and Laycock 2002). Within this era of ever-increasing social, economic and management complexity and resource constraint, law enforcement leaders are called upon by a broad range of stakeholders to make more rational and accountable decisions for problems and policy issues that fall under their mandate or control (Lister 2006; Sansfaçon et al. 2002; Sherman et al. 2002). Central to this paradigm of accountability is the overarching need for leaders and their organizations to be open to new information, knowledge, and ideas that may support, refute, or modify current policy and practice (Correia and Wilson 2001; Curry and Moore 2003; Simons 2005).

For the last two decades the business of policing, whether viewed from a crime fighting, crime prevention, and/or public service perspective, has been greatly influenced and impacted by a number of different, sometimes overlapping, and yet evolving policing policy and practice innovations. Among these are: policing competency development (Police Sector Council 2013); community policing (Gianakis and Davis 1998); problem-oriented policing (Sidebottom et al. 2012); hot-spots policing (Weisburd and Neyroud 2011); Compstat (Magers 2004); intelligence-led policing (Carter and Carter 2009); and evidence-based policing (Nutley et al. 2008). These innovations were implemented in response to the rising crime rates of the recent past as well as increased stakeholder dissatisfaction with police performance and problem solving. Within each of the previously mentioned policing models resides a set of information behaviours, values, and management requirements, which require not only a political and philosophical commitment from the leaders of the police organization but a technological and cultural commitment as well (Schaferet al. 2011; Scott 2000; Williams 2003). While the judgement as to what sources and types of information and knowledge practices are required for sound decisions and improved organizational performance in any given context can be contentious, the linkage between an organization's information knowledge management, information behaviour, beliefs, and values, and their impact on information use outcomes and performance are not (Alavi et al. 2005; Choo 2006; Choo et al. 2008).

An organization uses information for three primary purposes: 'to create an identity and a shared context for action and reflection'; to 'develop new knowledge and new capabilities'; and to 'make decisions that commit resources and capabilities to purposeful action' (Choo 2006: 27). Key, within the development of this shared context and reflection, is the need for organizations to make sense of the change around them. Recent studies describe this sense-making as the process by which individuals and organizations seek information to fill gaps in experience and knowledge when faced with uncertain, volatile, or otherwise equivocal environments (Choo 2001; Weick et al. 2005). It is therefore unsurprising that a dominant theme within the business management, economics, and sociology literature over the last two decades is that organizations need to innovate, adapt, and create new knowledge for action to survive within current business, economic, and social contexts (Fagerberg et al. 2005). This message has a particular salience to the public sector and policing organizations as they deal with issues and problems that are often highly complex, contestable, or intractable in nature but little empirical research testing these issues in the policing contexts has been conducted (Gardner 2011; Matthews et al. 2009; Prahalad and Krishman 2008).

Though much of this same literature is devoted to the topic of information and knowledge management, researchers have acknowledged that, in addition to the technical prerequisites for information and knowledge sharing, organizations must consider the softer aspects of effective information and knowledge collection and use, such as: organization context, social interaction, politics and organization culture (Curry and Moore 2003; Detlor et al. 2006; Schein 2010). Accordingly, this study applied Pan and Scarbrough's social-technical theoretical perspective where information and knowledge management are 'multi-layered systems, with loosely coupled technological, informational and social elements interacting over time to determine practical outcomes' (Pan and Scarbrough 1999: 362). These multi-layered systems are defined as follows: infra-structure is the information technology systems that allow members of the organization to have contact; info-structure is the formal rules that govern information exchange on the network; and info-culture is the embedded cultural knowledge that governs knowledge and information constraints (Pan and Scarbrough 1999: 362-363).

Organizational behaviour and values

Undisputedly, an organization's culture impacts the organization's ability to make sense of its environment, adapt, perform, innovate, and take action (Alavi et al. 2005; Balthazard et al. 2006; Thompson 2003). Present-day organizations face a variety of complex environmental, social, and financial volatility and chaos factors (Seijts et al. 2010). To develop effective decisions, policies and practices, reaction to these factors has increasingly emphasised the importance of information sharing, collaboration, and knowledge management within the private or public sector (Braga 2008; Choo 2006; Wren 2002). Whether viewed from a public policy or a private sector perspective, organizational culture plays a key role in the decision-making and action taking processes as the limits of personal and professional rationality are often confounded by a variety of factors, including: the norms, values and beliefs; shifts in attention, choices and preferences; incongruence between espoused values and theories in use; and shifting political coalitions within the organization (Argyris 1993; Janis and Mann 1977; Tversky and Kahneman 1974).

The culture of an organization may be broadly defined as a composite of the values, beliefs, norms and attitudes within the organization. Values are attitudes about the worth or importance of people, concepts or things. Norms are the socially shared standards that provide guidance and indicate the expected behaviour, and attitudes are the mind-sets of individuals within the organization. One way of viewing the sets of values, beliefs, norms, and assumptions that belong to those participating in the achievement of the organization's tasks is that they are the 'rules of the game' and that these 'organizational games are mixed motive games of coordination and conflict, of cooperation and contestation' (Ocasio 1997: 196). Simply put, rules, written and unwritten, guide organizational life. Another view of organizational rules suggests that:

Rules in organizations can be seen both as products of learning and as carriers of knowledge…rules evolve as organizations solve the political and technical problems they face and how they mediate interactions between the actions and lessons of the past and those of the present. (March et al. 2000: 3)

Thus, written and unwritten organizational rules essentially guide, shape, and influence information and knowledge acquisition, innovation, and use, along with the outcomes that are derived from the application of that information and knowledge. These written and unwritten rules are of critical importance to policing as rank and file officers are not only guided by these rules, but these rules impact (positively or negatively) the achievement of goals, including: problem solving, creating work that is beneficial, and information sharing.

Organizational goals and outcomes

Organizational theory and thinking has shown that organizations are highly complex, dynamic, and interactive social, economic and political systems that rely on their interaction with their external environments for materials, resources and information (Daft 2009; Pondy and Mitroff 1979). The same materials, resources and information inputs 'yield some outcome that is then used by an outside group or system' (Katz and Kahn 1978: 3). Yet, relatively little is known about the utilization by policing organizations of their knowledge and information capabilities to achieve three key information use outcomes: problem solving, creating work that is beneficial, and information sharing. These three outcomes, individually and collectively, play foundational roles in contemporary North American policing by supporting a broad range of strategic, operational, and human resource management initiatives, including, but not limited to, problem-oriented policing, community policing, intelligence-led policing, and police competency requirements (Braga and Weisburd 2007; Peterson 2005; Police Sector Council 2013).

Problem-solving incorporates a personal and/or professional need to seek information to address cognitive gaps, to deal with stress caused by problem equivocality, risks, and to deal with contextual factors associated with specific problems (Moldoveanu 2009; Simon et al. 1987). Each of these problem states and problem-solving activities are intricately linked to all forms of police practice, including those that employ systematic problem scanning, analysis, response and assessment, or other related steps (Boba and Crank 2008; Royal Canadian Mounted Police 2008). Creating work that is beneficial is critical to all organizations, private and public sectors alike, but when it is considered within the context of a police organization, this outcome naturally extends itself beyond the confines of the police agency and out into the communities it serves. Information sharing, formal and informal, is a keystone to modern police practice and forms the base for all models of policing to one extent or another (LeBeuf and Paré 2005; Plecas et al. 2011).

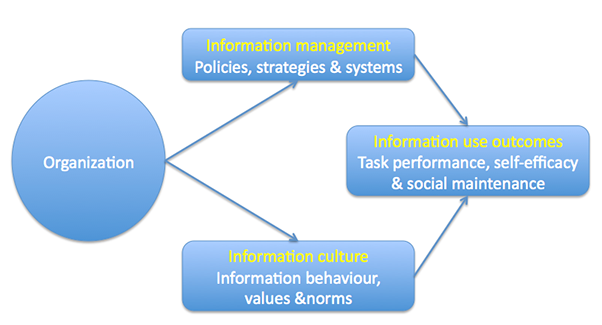

Recent research findings of Choo et al. (2006) and Bergeron et al. (2007), derived from an examination of organisations in the health science, legal, and engineering fields, suggested that the information culture of an organization can be identified by examining the information management, behaviours, and values of its members. Further, Choo's and Bergeron's research findings indicated that each organization's information behaviour and values are unique and that these unique sets of behaviour and values can account for significant proportions of variance in information use outcomes. An illustration of the conceptual framework utilized by both Choo and Bergeron is provided in Figure 1.

Research into organizational information culture and its impact on information use outcomes, however, has been limited to a small number of organisation types. The current study addressed this gap by exploring whether the theoretical framework used by Choo et al. (2006) and further explored by Bergeron et al. (2007) was applicable to the field of policing. The information constructs and factors used within this study were conceptually framed and operationalized as follows.

Information management: broadly labelled as the 'information policies, strategies and systems' of the organization (Bergeron et al. 2007: 2). A full explication of the various meanings of information management within organizations is beyond the scope of this paper, however, succinctly stated 'information that is acquired or created has to be organized and stored systematically in order to facilitate sharing and retrieval' (Choo 2002: 33). It is within this acquisition, creation, storage, sharing and retrieval domain that the various organizational policies, strategies and information systems reside. Information policies, within organizations, generally consist of the various formal regulations, guidelines or positions of the organization as they relate to: information and data, information processing equipment, information systems and services, and staff roles and responsibilities (Lytle 1988). In previous research a set of fourteen survey items gathered information on four information management topics, namely 'information policy, formal procedures, training and mentoring' (Choo et al. 2006: 497). The same items and information management topic coverage was implemented by Bergeron et al. (2007) to examine information management in private sector organizations.

Information culture: or the information values, norms and behaviour of the organization, determines how information is used and applied within the organization (Bergeron et al. 2007: 2). Prior studies incorporated a total of twenty-eight survey items that were designed to gather data about larger organizational information behaviour and values areas of information integrity, (in)formality, control, transparency, sharing and proactiveness (Bergeron et al., 2007: 2; Choo et al. 2006: 497). The definitions used for each of these six constructs are as follows: (1) Information integrity: 'the use of information in a trustful and principled manner at the individual and organizational level'; (2) Information formality: a 'willingness to use and trust institutionalized information over informal sources'; (3) Information control: 'extent to which information about performance is continually presented to people to manage and monitor their performance'; (4) Information transparency: 'openness in reporting and presentation of information on errors, failures and mistakes'; (5) Information sharing: 'the willingness to provide others with information in an appropriate and collaborative fashion'; and (6) Information proactiveness: 'the active concern to think about how to obtain and apply new information in order to respond quickly…and to promote innovation' (Choo et al. 2006: 494-495).

Information use outcomes, encompasses task performance, self-efficacy and social maintenance (Bergeron et al. 2007; Choo et al. 2006). Both researchers used a total of five questions to elicit responses pertaining to task-related outcomes where 'information was used to solve problems or innovate' (Bergeron et al. 2007; Choo et al. 2006).

Awareness of the nature and quality of organizational information management, behaviour, and value variances allows organizations to identify potential strengths and/or weaknesses in the information culture; assess congruence between stated and observed values, goals, and outcomes; and assess their ability to achieve key information use outcomes.

Research aims

The aim of this study was to contribute to both theory and professional police practice by testing the applicability of the conceptual framework used by Choo et al. (2006) and further explored by Bergeron et al. (2007) within a law enforcement context and culture. The robustness of the model was tested by means of an indirect comparison of information behaviours and values within three Canadian policing organizations and those previously investigated in non-policing organizations. The current study examined the same underlying constructs with minor changes in terminology to categorize the information use outcomes to better reflect policing environments. Specifically, the research examined which information factor constructs had the most impact on the information use outcomes of problem solving, creating work that is beneficial, and information sharing in policing. It was hypothesized that the information sharing factor would have the greatest impact on the information outcomes of problem solving, creating work that is beneficial, and information sharing since this element is the cornerstone of contemporary policing methods and models (LeBeuf and Paré 2005).

Method

Materials

A Web-based self-completed survey questionnaire was designed, consisting of sixty-three questions. The questions sought a combination of closed and open-ended responses and took approximately twenty minutes to complete. This article reports on responses to thirty-five survey items focussing on three dimensions: information management, information behaviour and values, and information use outcomes, i.e. , 28 items associated directly with the independent variables information management and information behaviour and values and seven items associated with the dependent variable information use outcomes derived from previously validated instruments (Bergeron et al. 2007; Choo et al. 2006). The survey items and overall information behaviour and value construct associated with information control (Bergeron et al. 2007; Choo et al. 2006) were omitted due to lack of substantive value, as indicated via previous research outcomes. The three information use outcomes task performance, self-efficacy, and social maintenance were grouped under new headings of problem solving, creating work that is beneficial to the organization, and information sharing, respectively. These new groups were based on each of the three individual information use outcomes survey question groups, the focus of those questions, and applicability to the current context.

Independent measures

Information management. This contained ten items about organizational information policies and procedures, and support and mentoring mechanisms (see Appendix 1). Reliability and validity of this dimension were previously tested by Choo et al. (2006: 498) yielding Cronbach's alphas of 0.90 (explicit) and 0.75 (tacit) respectively, thus positively confirming these measures. Previous factor analysis revealed that the explicit and tacit components of information management loaded cleanly on to the two factors and overall contributed 57.8% of the common variance (Choo et al. 2006: 498).

Information behaviour and values. This second dimension consisted of eighteen questions probing the five separate constructs of information: informality; integrity; pro-activeness; sharing; and transparency (see Appendix 1). The reliability and validity of these construct scales were (Choo et al. 2006) positively and significantly correlated to information use outcomes, with Cronbach's alphas above the 0.65 to 0.70 range, within an acceptable level per the framework used by Choo et al. (DeVellis 1991): informality (α = 0.67), integrity (α = 0.72), pro-activeness (α = 0.78), sharing (α = 0.66), and transparency (α = 0.80). Additionally, Choo et al. (2006) found that these five factors contributed to 60% of the common variance. The sixth factor, information control, 'did not show up in this study' (Choo et al. 2006: 501) and was therefore omitted from the current study.

Dependent measures

Information use outcomes. This last dimension of the model used five questions to garner information specific to the outcomes of problem solving, the creation of work that is beneficial, and the information sharing domains (see Appendix 1). Reliability and validity of this dimension was previously tested (Choo et al. 2006), where the Cronbach alpha score of 0.67 and correlations between the information management and information behaviour and value variables were all positively and significantly correlated to information use outcomes. The 0.67 Cronbach value indicated sufficient dimension reliability and validity while the significant and positive correlations between the information management, information behaviour and values, and information use outcomes indicated that a relationship existed, where positive increases in information management and/or information behaviour and values produced a positive increase in the information use outcomes. This study added two new information use outcome questions, which explored participants' level of agreement with two statements: 'My work tasks demand that we use enforcement and crime prevention policies/procedures that have been successful in the past' and 'My work is guided by the most current research on law enforcement/crime prevention policies and practices'. Both questions devised by the authors, were pilot-tested prior to implementation, with no issues identified, and served to identify to what extent evidence-informed policy and practice was perceived in the three police organizations. In response to each of the question items, participants indicated their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert type scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree), or an additional sixth response option 'do not know'.

Sampling procedures

Invitations to participate in the study were issued to police chiefs in diverse Canadian law enforcement agencies. Three police agencies agreed to participate within the data collection period: one medium sized independent municipal agency (MED-IND), one medium sized Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) municipal police agency (MED-RCMP), and one large sized independent municipal agency (LRG-IND), thus providing mixed law enforcement perspectives. Agency size was determined based on the authorized strength or the budgeted number of sworn police officers in the target year. The medium-sized agencies employed 200-300 sworn officers and the large agency employed in excess of 300 sworn police officers.

Sworn police officers within each of the three participating organizations were informed of the study by letter from the Chief Constable or Officer in Charge of the agency, and were sent individual e-mail invitations containing Web-based survey links. The MED-RCMP municipal agency is a federally controlled entity, thus that survey was administered in English and French, the two official languages of Canada. The survey was open for two months during which period three e-mail reminders were issued. Survey completion took approximately twenty minutes. All sworn officers (N = 1850) within the three organizations had the option to participate, therefore were self-selecting.

Participants

A total of 134 participants completed all demographic questions and the number and percentage of participants, by agency, was as follows: large independent municipal agency (n = 74, 55%), medium-sized independent municipal agency (n = 31 23%) and medium-sized Royal Canadian Mounted Police (n = 29 22%). Of the combined participants, 84% were men and 16% were women. Furthermore, 49% of the participants were ranked Constables (line personnel); 43% were ranked Corporals, Sergeants, or Staff Sergeants (supervisors); and only 4% were Inspectors, Superintendents, Chief Superintendents, Deputy Chiefs or Chief (command). The ratio of male to female respondents is consistent with the most current Canadian police statistics which indicate that 80.8% of Canadian police officers are male and 19.2% are female (Statistics Canada 2010). The ratio of line personnel and supervisor response rates were not representative of the larger Canadian rank/role demographic where line personnel and supervisors represent approximately 71% and 25% of the police population respectively, while the command level representation was appropriate at the 4% ratio (Statistics Canada 2009).

Almost one half of the participants (48%) reported some college education, and two-fifths (41%) indicated they had completed a four year college or university degree. Few participants (3%) had completed a graduate degree. The remainder (6%) reported completion of high school or their general education development (GED).

Analysis

Data were analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 18 software. Descriptive statistical analysis was initially used to screen data, identify potential outliers, and characterize differences at the group or case level. A univariate generalised linear model (GLM) modelled information use outcome on the basis of information behaviours and law enforcement category. This was followed by factor analysis, to reduce information behaviours into a smaller number of factors. Finally, a univariate GLM was again used to model information use outcomes, this time on the basis of the newly extracted factors and law enforcement category. Statistical significance (p) was measured at the 0.05 and 0.001 levels.

Results

The means and standard deviations for each of the independent and dependent variables, by organization, are provided in Table 1.

| Independent variables | Organization | n | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information proactiveness | MED-IND | 30 | 3.48 | 0.82 |

| LRG-IND | 75 | 3.23 | 0.88 | |

| MED-RCMP | 29 | 3.38 | 0.73 | |

| Information sharing | MED-IND | 30 | 3.53 | 0.74 |

| LRG-IND | 75 | 3.40 | 0.76 | |

| MED-RCMP | 29 | 3.66 | 0.63 | |

| Information management | MED-IND | 30 | 3.39 | 0.72 |

| LRG-IND | 77 | 3.40 | 0.72 | |

| MED-RCMP | 29 | 3.77 | 0.75 | |

| Information transparency | MED-IND | 30 | 3.72 | 0.80 |

| LRG-IND | 76 | 3.58 | 0.90 | |

| MED-RCMP | 29 | 3.75 | 0.57 | |

| Information integrity | MED-IND | 30 | 2.48 | 0.58 |

| LRG-IND | 76 | 3.02 | 0.74 | |

| MED-RCMP | 29 | 2.78 | 0.65 | |

| Dependent variable | ||||

| Information use outcomes | MED-IND | 30 | 3.99 | 0.51 |

| LRG-IND | 75 | 3.72 | 0.50 | |

| MED-RCMP | 29 | 3.89 | 0.44 | |

Pearson product moment correlations of organization type and information behaviour and values are provided in Table 2.

| Correlations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Orgzn. type | Pro-activeness | Sharing | Management | Transparency | Integrity |

| Orgzn. type | 1 | -0.03 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Proactiveness | -0.03 | 1 | ***0.64 | 0.20 | **0.23 | -0.14 |

| Sharing | 0.06 | ***0.64 | 1 | *0.24 | *0.19 | -0.12 |

| Management | 0.14 | 0.20 | *0.24 | 1 | ***0.61 | **-0.35 |

| Transparency | 0.01 | **0.23 | *0.19 | ***0.61 | 1 | ***-0.51 |

| Integrity | 0.04 | -0.14 | -0.12 | **-0.35 | ***-0.51 | 1 |

| Note: * p <0.05; ** p <0.01; ***p<0.001 (two-tailed). | ||||||

No statistically significant correlations between organization type and the five target information behaviours and values emerged. Statistically significant correlations between the five information behaviour dimensions are shown in Table 2.

A univariate generalised linear model was fitted, modelling information use outcome on the basis of information behaviour (information proactiveness, management, integrity (reverse scored), sharing, and transparency) as well as law enforcement category (MED-IND, LRG-IND, RCMP) (see Model 1, Table 3), thereby testing the hypothesis that the information sharing factor would have the greatest impact on the information outcomes of problem-solving, creating work that is beneficial, and information sharing in policing.

| Model 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Level | B | SE | Sig. | Adj. R2 |

| Constant | 1.63 | 0.29 | 0..00** | 0.43 | |

| Law enforcement category | Category 1 (MED-IND) | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.25 | |

| Category 2 (LRG-IND) | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.87 | ||

| Category 3 (MED-RCMP) | 0.00 | - | - | ||

| Information behaviour | Management | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.03* | |

| Sharing | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.18 | ||

| Pro-activeness | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.00** | ||

| Transparency | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.26 | ||

| Integrity | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.18 | ||

| Note. Dependent variable = information use outcomes, *p<0.05. **p<0.01 | |||||

The results of Model 1 indicated that the independent variables were significantly associated with information use outcomes: F (7,124) = 14.30, p<0.001), accounting for 43% of the variance. The regression analysis revealed that both information pro-activeness (F (1,124) = 24.13, p<0.001) and information management (F (1, 124) = 5.05), p = 0.026) significantly predicted information use outcomes whereas information integrity (F (1, 124) = 1.79, p =0.184), information sharing (F (1, 124) = 1.80, p = 0.182), and information transparency (F (1,124) = 1.29, p = 0.259) were not individually significant predictors of the information use outcomes of problem solving, information sharing, and creating beneficial work within the police organizations. However, information integrity, information sharing, and information transparency were all associated with positive increases in the information use outcome variable.

Factor analysis on the five key information constructs of information management, information sharing, information pro-activeness, information integrity (reverse scored), and information transparency was conducted to extract the underlying dimensions. The five information constructs loaded onto two underlying factors, shown in Table 4.

| Factors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | 1 | 2 |

| Information management (α = 0.89) | 0.76 | |

| Information sharing (α = 0.71) | 0.89 | |

| Information pro-activeness (α = 0.84) | 0.90 | |

| Information transparency (α = 0.73) | 0.85 | |

| Information integrity (reverse scored) (α = 0.75) | 0.76 | |

| Eigenvalues | 2.17 | 1.37 |

| Percentage of variance | 37.73 | 33.01 |

Combined, these two factors yielded a cumulative common variance of 71% within the information behaviour and values dimensions. The first factor, which incorporated the three constructs of information management, information transparency, and information integrity, denoted the importance of information quality control within the context of these three police organizations. This new factor accounted for 38% of the common variance within these three police organizations. The second factor, which incorporated the constructs of information sharing and information pro-activeness accounted for 33% of the variance, exemplified the importance of proactive collaboration within these same three organizations.

A second multiple regression (Model 2, Table 5) was conducted using the two new factors that were identified within the factor analysis process: information quality control (composed of the constructs information management, transparency, and integrity); and pro-active collaboration (compiled of the constructs information sharing and pro-activeness).

| Model 2 (two new factors) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Level | B | SE | Sig. | Adj. R2 |

| Constant | 1.61 | 0.29 | 0.00** | 0.41 | |

| Law enforcement category | Category 1 (MED-IND) | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.16 | |

| Category 2 (LRG-IND) | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.73 | ||

| Category 3 (MED-RCMP) | 0.00 | - | - | ||

| Information behaviour | Information quality control | 0.27 | 0.07 | 0.00** | |

| Pro-active collaboration | 0.38 | 0.05 | 0.00** | ||

| Note. Dependent variable = information use outcomes, **p<0.01 | |||||

The results of the regression indicated that the two new information behaviour factors, information quality control and pro-active collaboration, were significantly related to information use outcomes, F (4, 124) = 22.281, p = 0.000, and adjusted R2 = 0.407.

Model 2 was statistically significant and accounted for 41% of the variance in information use outcomes within the three police organizations. The regression analysis revealed that both information quality control (b = 0.265, p<0.001) and pro-active collaboration (b = 0.380, p<0.001) significantly predicted information use outcomes within the three participating police organizations.

When comparing the original information factor regression model (Model 1) to the new two-factor model (Model 2), despite the finding that both regression models were statistically significant overall (p<0.001) and that both models had similar dependent variable predictive capabilities (43% and 41% respectively) the following subtle but important improvements were observed in Model 2. First, the statistical significance for the relevant information behaviour and values increased and the effect sizes (values of partial eta squared) for the statistically significant variables increased: information quality control (ηp2 = 0.123) and pro-active collaboration (ηp2 = 0.305) versus Model 1 management (ηp2 = 0.041) and pro-activeness (ηp2 = 0.171). For every unit increase in information management and pro-activeness within Model 1 there was an expected 0.139 and 0.282 increase in information use outcomes, however, there was a greater increase in information use outcomes within Model 2 as information quality control achieved an expected 0.265 increase and pro-active collaboration achieved an expected .0380 increase in information use outcomes.

Discussion

We indirectly tested the robustness and applicability of the information behaviours and values model applied previously in organizations within the health sciences, legal, and engineering fields (Choo et al. 2006; Bergeron et al. 2007) and found that this model was applicable to policing organizations. The findings regarding information use outcomes applied the social-technical theoretical perspective and supported Pan and Scarbrough's premise that 'such systems involve more than technology but rather a culture in which new roles and constructs are created' (1999: 372). In support of this conclusion the following is offered.

This study examined which information factor constructs had the most impact on information use outcomes of problem solving, creating work that is beneficial, and information sharing within the three police organizations and compared the findings of previous research to those obtained in this study. Within a public health organization factor analysis revealed that the information culture of the organization, (indicated by the statistically significant influence of information behaviours such as sharing, proactiveness, and transparency), accounted for 29% of the common variance in the achievement of the information use outcomes (Bergeron et al. 2007). Similarly, within a large law firm, employee information behaviour and values surpassed information management in the achievement of their information use outcomes of task performance, self-efficacy, and social maintenance (Choo et al. 2006). Specifically, the information culture of the law firm (indicated by the information behaviour and values of sharing, proactiveness, transparency, and informality) accounted for 38% of the variance in the organization's ability to achieve information use outcomes.

Unlike these previous findings, our analysis of the main effects indicated that both information behaviour and values and the information management constructs were significant factors in the achievement of information use outcomes within policing. Specifically, information pro-activeness and information management had the most impact on information use outcomes within three different policing organizations, with pro-activeness accounting for 28% of the common variance and information management accounting for 14% of the variance.

Consideration of the larger field of law enforcement indicated that these factors were not out of line in terms of their focus or direction for the following reasons. The information behaviour and value pro-activeness was defined as 'the active concern to think about how to obtain and apply new information in order to respond quickly…and to promote innovation' (Choo et al. 2006: 494-495) and information management was defined as the 'information policies, strategies and systems' of the organization (Bergeron et al. 2007: 2). North American law enforcement organizations must continually keep abreast of community needs, changing laws and technologies, as well as innovative crimes and potential solutions. Further, these same law enforcement organizations must obtain, store, disseminate, and apply new information and knowledge on a daily basis to function within the currently volatile social, economic, and technological environment. It was therefore unsurprising that the information management factor was retained within the policing context and not within the previously studied organizational contexts (Luen 2001). The implication for policing is that information management, as one side of the socio-technical equation, serves an important function in the achievement of outcomes through effective information policies, strategies, and systems.

Factor analysis conducted on the information management and information behaviour and values identified two new factors within this policing context: information quality control, a composite of information management, transparency, and integrity; and pro-active collaboration, comprised of information sharing and proactiveness. The first factor, information quality control, accounted for 38% of the variance and the second factor, pro-active collaboration, accounted for 33% of the common variance as it related to the information use outcome main effects. These new factors, within this policing context, not only support the idea that contemporary police organizations are knowledge and information intensive but they provide what stake holders have been demanding from their police organizations and personnel for many years: better information management, increased information transparency and integrity, as well as improved information sharing (LeBeuf and Paré 2005; Police Sector Council 2011). Further research, however, will be required to assess the prevalence and longevity of these two factors within the policing context in Canada and elsewhere.

We had hypothesised that information sharing would have the greatest impact on the information outcomes of problem solving, creating work that is beneficial, and information sharing within this policing context. Since information sharing did not have a statistically significant main effect on information use outcomes, and was overshadowed by information pro-activeness and information management, this hypothesis was not supported. Information pro-activeness and information management capabilities, however, enable organizations to adjust to volatile external environments, quickly shape strategies, and innovate as needed and these capabilities are complimentary to the current social, financial, and political climate of policing.

Contributions and limitations

The findings of this study contributed to the literature by testing and extending existing research findings within a new context, namely contemporary Canadian policing agencies. The findings of this study were supportive and generally consistent with those of previous studies conducted by Choo et al. (2006) and Bergeron et al. (2007). The larger constructs of information management and information culture did indeed account for significant proportions of variance in information use outcomes within the policing context, and further support was provided for the notion that within a specific field, each organization has unique information behaviour and values. Thus, this study extended the existing theoretical stance to incorporate the information use outcomes of problem solving, creating beneficial work, and information sharing. More importantly, this study identified two new factors, information quality control and pro-active collaboration, that contributed significantly to the achievement of these same three foundational outcomes within the policing context.

The primary limitation of this study, however, was the small sample: despite attempts to secure a larger more representative sample within the two-month study period, the nature of operational police work at the rank and file level within the participating agencies impacted completion rates.

The majority of the officers participating in this study were operational police, who have little to no time for anything but primary work tasks, which includes: attending calls for service; conducting criminal investigations and follow-ups; conducting interviews; dealing with prisoners; completing associated investigative reports and judicial reports; and attending in-house and external training sessions. Beyond the significant organizational and operational burdens on Canadian police (McCreary and Thompson 2006), Canadian police organizations also experience a high survey burden (Weiner and Dalessio 2006). Survey burden and fatigue has become more pronounced as sworn officers are increasingly asked to respond to a myriad of surveys covering topics such as leadership, stress, work-life relationship, and employee satisfaction surveys (Statistics Canada 2011; MacRae et al. 2005; Police Sector Council 2011; Royal Canadian Mounted Police 2013).

Implications for future research

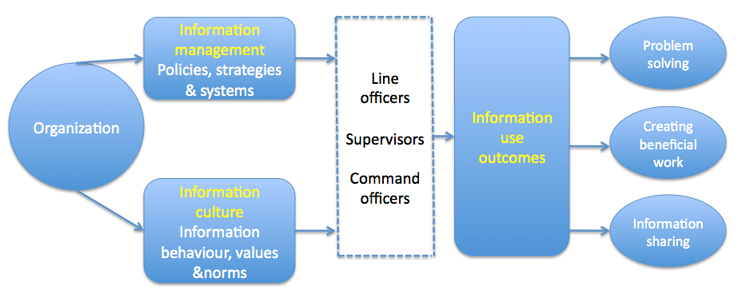

The implications for future research are many. When we speak of information behaviours, values, and information use outcomes as they relate to police organizational information culture, problem solving, creating work that is beneficial and information sharing, we are speaking of subject areas that ultimately define, support, and guide the public policies, practices, and the actions of the sworn officers and the organizations that they serve. While caution is advised in generalizing these findings to all policing organizations, they provide a framework for future research and analysis. The theoretical model utilized within this study has established a sound basis upon which further research may be conducted since a nexus exists between the constructs of information management, information behaviour and values (culture), and information use outcomes, whether explored within a health sciences, legal, or policing context. It is suggested that future theoretical models, when implemented within the field of policing, should also incorporate the constructs of information management, information culture, and information use outcomes, while recognizing the mediating role of each level of officer in the achievement of outcomes and extend the outcomes so that each of the three outcomes are developed as separate and unique scales. This would enable police organizations to specifically assess their existing capabilities in relation to their line, supervisor, and command level officers and the achievement of each and/or all information use outcomes. Therefore, the following conceptual diagram is offered (Figure 2).

Further research and scale development is required with respect to the three individual information use outcomes of problem solving, creating beneficial work, and information sharing. An analysis of these sub-scales revealed low individual scale reliability, thus they were not sufficiently robust to stand on their own using the current sample. Future research with larger samples and development of these sub-scales would reveal whether these scales could be used for increased discrimination within the larger information use outcome factor. Additionally, future large-scale research would yield a broader and deeper understanding of the nature and quality of the information behaviour and value elements from a number of potential perspectives, including: agency type, policing model employed, and sworn officer rank, age, and years of service. Such delineations would provide a rich description that could be used to identify human resource hiring and training requirements, organization sub-culture differences, which support or hinder the achievement of strategic goals and outcomes, and technical, operational, and administrative needs that may exist at various rank, service, and/or age stratifications within the organization.

Implications for policy and practice

The refinement and development of information use outcome scales that are specifically focused on the three police related and individual foundational outcomes of problem solving, creating work that is beneficial, and information sharing have direct implications for police policy and practice. Specifically, such refinement and development of individual information use outcome scales will allow police organizations to assess whether there is congruence between the organizations' desired values, strategies, goals, and outcomes and the values, norms, and behaviours that actually exist at the individual unit and/or officer level and the outcomes that are then realized. Such levels of analysis and understanding will not only enhance public sector accountability and performance management within policing but will allow police leaders to identify, appreciate, and better understand the information management and culture gaps that may exist between the organization and the front line personnel who support the day to day operation of the organization. This awareness and understanding is critical to all police organizations as the actions of rank and file staff, individually and collectively, invariably impact the achievement of three foundational information use outcomes: problem solving, creating work that is beneficial, and information sharing.

About the authors

Doug Abrahamson, DPP, MBA is a police officer with the Victoria Police Department, British Columbia, Canada. His professional doctorate in public policy is from Charles Sturt University - Australian Graduate School of Policing. He served as a senior research fellow with the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF) in Washington, D.C. and currently serves on the Board of Directors for the Victoria Restorative Justice Society (Canada). His research interests include organizational accountability, culture, information use outcomes, performance, restorative justice, risk management, and the application of evidence-based policy and practice within policing. He can be contacted at: dabrahamson@shaw.ca

Jane Goodman-Delahunty, JD, PhD, is a Research Professor at Charles Sturt University Manly Campus, Australia. Trained in law and experimental psychology, her expertise is the application of empirical methods to inform legal practice and policy. Her current research is funded by the Australian Research Council, the Australian Institute of Criminology, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation and the NSW Police Force. She is President of the Australia and New Zealand Association of Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, a past President of the American Psychology Law Society, and former Editor of Psychology, Public Policy and Law. She can be reached at: jdelahunty@csu.edu.au