Perceptions of fear appeal and preferences for feedback in tailored health communication: an explorative study among pre-diabetic individuals

Heidi PK Enwald and Terttu Kortelainen, Information Studies; Juhani Leppäluoto, Department of Physiology, Institute of Biomedicine; Sirkka Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi, Institute of Health Sciences, Unit of General Practice; Timo Jämsä, Department of Medical Technology, Institute of Biomedicine; Harri Oinas-Kukkonen, Department of Information Processing Science; Karl-Heinz Herzig, Department of Physiology, Institute of Biomedicine; Maija-Leena A Huotari, Information Studies, Faculty of Humanities.

FI-90014, University of Oulu, Finland

Introduction

Research on health information behaviour is still quite rare. It has focused on health information seeking (e.g., Johnson and Case 2012; Marton and Choo 2011) in general and on particular medical conditions, such as cancer or AIDS or the potential for these diseases (Case 2012). This study contributes to this limited body of research by focusing on the use of health information and the individual characteristics of the information user in the context of health promotion.

In health promotion, effective health communication is a prerequisite for initiating, changing and sustaining healthy behaviour. An understanding of how the individual information user perceives the content of health information is critical for promoting healthy behaviour. However, issues related to health typically tend to be anxiety-laden and associated with negative rather than positive feelings. Some individuals even have a tendency to avoid information that they find threatening or distressing, such as information related to diseases (Sairanen and Savolainen 2010.) Therefore, it is important that relevant and suitable health information is easily available (Johnson and Case 2012; Dervin 2005; Tuominen 2004). Tailoring of health communication could increase the possibility that the information content is processed and accepted by the receiver to enhance healthy behaviour. Even minor differences in an individual's reception of the content of information should be given attention when planning tailored health communication. It has been stated that the reasons behind individual differences in health information behaviour should be taken into consideration in tailoring health information for information services (Ek and Heinström 2011; Bar-Ilan et al. 2006; Fourie 2008). However, few information services reflect a detailed understanding of information behaviour (Hepworth 2007; Fidel and Pejtersen 2004).

The empirical study reported here was conducted among individuals diagnosed with pre-diabetes who volunteered to participate in a physical activity and diabetes prevention intervention trial (PreDiabEx) in Northern Finland for three months from January to March 2010. Pre-diabetic individuals are especially vulnerable to developing type 2 diabetes in a short time-frame. Adiposity, unhealthy diet and a sedentary lifestyle are risk factors of pre-diabetes (formerly called borderline diabetes) and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ageing increases the risk of type 2 diabetes and it is also associated with the level of education; people in developed countries with a higher level of education have a lower risk (Uusitupa et al. 2011.) In pre-diabetes an individual's glucose tolerance is impaired, but still below diabetic levels. This slow initial phase is usually asymptomatic and may last for many years. In Finland around 42% of men and 33% of women are in pre-diabetic or diabetic states (Saaristo et al. 2010). Increased physical activity and weight loss have been shown to prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes (Uusitupa et al. 2011) and behaviour change can be addressed successfully with lifestyle counselling (Saaristo et al. 2010). Effective health communication plays a central role in health promotion. A previous study among pre-diabetic individuals showed that those whose physical health status was poor desired to receive tailored information on nutrition and physical activity more frequently (see Enwald et al. 2012). This study further investigates the relationship between information reception and health status.

For optimal results in tailoring health information, the style of presenting the health message content should be carefully considered (Ivanov 2012). Messages can be framed in several ways by using message strategies, and tailored health communication can also be based on these strategies. One strategy is the use of emotional appeals. Emotional appeals range from humour to sympathy. Fear appeal has received the most attention (Stiff and Mongeau 2003). A fear appeal message strategy is defined as persuasive communication that presents threatening information to arouse fear to promote safer behaviour (Rogers 1983). Another message strategy, feedback, involves presenting individuals with information about themselves, obtained during assessment or elsewhere (Hawkins et al. 2008). Perception of fear appeal and preferences for feedback form part of the reception of information, which is the initial phase of information use.

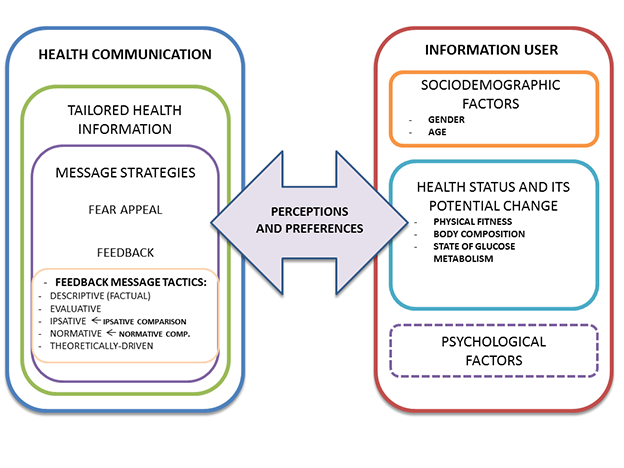

This study aims to increase understanding about users of information and their individual characteristics related to information use from the perspective of information reception. The study focuses on fear appeal and feedback message strategies, which can be utilised to tailor health communication. It is assumed that individuals are more receptive to messages that they prefer than ones that they do not. Individual preferences for a feedback message strategy are explored by means of five different feedback message tactics: descriptive (factual), evaluative, normative, ipsative and theoretically driven. Methodologically, this explorative study provides a novel contribution by combining subjective methods with objective physical measurements.

The objective of this study is to specify individual differences in perceptions of a fear appeal message strategy and preferences for feedback message tactics particularly in relation to sex, age, physiological health status (identified by objective measurements of physical fitness, body composition and glucose homeostasis) and changes in health status during the trial.

The research questions are stated as follows:

- How is a fear appeal message strategy perceived by the pre-diabetic individuals participating in the PreDiabEx intervention trial?

- Which feedback message tactics are preferred among the pre-diabetic individuals?

- Do perceptions of a fear appeal message strategy and preferences for feedback message tactics vary according to the age and sex of participants?

- Do perceptions of a fear appeal message strategy and preferences for feedback message tactics vary according to pre-diabetic individuals' physiological health status (physical fitness, body composition or glucose homeostasis) or according to possible improvement in health status (physical fitness, body composition or glucose homeostasis) during the three-month trial?

Theoretical background

The aspects of health communication and the information user's individual characteristics are combined in this study as outlined in Figure 1 below.

Information behaviour and information use

Information behaviour is the totality of human behaviour in relation to sources and channels of information, including information needs, seeking and use (Wilson 2000). It is determined by the interplay of demographic, cognitive, affective and behavioural factors (Hepworth 2007). For instance, self-efficacy, referring to an individual's belief in his/her own ability to successfully perform a specific task, is an important psychological factor related to health information behaviour.

This study focuses on information use in the context of health. However, there is no consensus on how to define information use (Savolainen 2009). For instance, according to Cole and Leide (2006), information use is a process in which an environmental stimulus, which includes stimuli obtained from reading, viewing and listening activities, modifies the user's knowledge structure. The concept information reception has been used to define the first stages of the information use process, which include noticing, filtering, evaluating and comparing the content of the obtained information (Nahl and Bilal 2007). In this study information reception is related to perceptions of and preferences for different kinds of message presentations, in other words, message strategies used in health communication.

Health communication and tailoring health information

Tailored health communication has been defined as any combination of information and behaviour change strategies intended to reach one specific individual, based on characteristics that are unique to that individual, related to the outcome of interest and defined on the basis of individual assessment. (Kreuter et al. 1999.) Tailoring attempts to increase both the relevance and suitability of health communication.

Fear appeal message strategy

Fear appeal is often used in marketing and social policy (see e.g., De Villiers 2008) and is best known for being used in health warning texts on cigarette packs and in road safety campaigns. Reviews of studies have found that fear appeal has a moderating effect on changing attitudes, intentions and behaviour (Contento 2011). Many social cognitive theories suggest that providing threatening information is effective in promoting safer and recommended behaviour, though empirical findings on this are less conclusive (Ruiter et al. 2003).

Feedback

Tailored feedback is based on information on the individual's characteristics (DiClemente et al. 2001). A key to providing tailored feedback is to refer back to how the individual answered certain assessment questions, evaluate this response and then provide tailored feedback. Feedback directs individuals' attention to their own characteristics or behaviour that they need to address, improve or change (Lustria et al. 2009). There are different kinds of feedback tactics and different kinds of categorisations of these tactics. In this study one kind of adapted categorisation of feedback message tactics is used. The tactics discussed are descriptive (factual), evaluative, normative, ipsative and theoretically driven.

Descriptive (factual) feedback message tactics refer to delivering individuals summarised information about their attitudes, beliefs or behaviour based on their self-assessment or observational data (Hawkins et al. 2008), or about a relevant health parameter, for example, blood pressure or cholesterol level (DiClemente et al. 2001). Descriptive (or factual) feedback may stimulate self-referential thinking about behaviour, and it may create a feeling of being understood (Hawkins et al. 2008). An evaluative feedback message may, for instance, include a specialist's evaluation of individual behaviour or comments on progress in targeted behaviour (Hawkins et al. 2008) or information about a person's state, of which he or she may not be fully aware. Normative feedback refers to a comparison of an individual's behaviour with that of peers or a social norm (Lustria et al. 2009). Normative and ipsative feedback are based on comparison. Normative feedback is based on social (or normative) comparison and it can be used to correct misperceptions about the behaviour of peers. For example, an individual's amount of physical activity could be compared to the amount of peers' physical activity. Normative comparison helps in interpreting given information and in estimating how one's own behaviour or risks compare with risks associated with another person (Kiviniemi and Rothman 2010). Ipsative (iterative or longitudinal) feedback is based on a comparison of an individual's current responses with their responses at the previous trial time point (Noar et al. 2007). Ipsative comparison is most suitable for individuals who are motivated by their own achievements. Theoretically driven feedback includes theory-based argumentations, for example, an explanation of the reasoning used to generate the feedback and justifications for the conclusions drawn (Lustria et al. 2009).

Psychological factors affecting reception of message strategies

In health communication it is important to note that health messages may threaten an individual's self-image and that self-image maintenance processes affect the way an individual accepts personally relevant messages. The theory of self-affirmation states that individuals are motivated to maintain the integrity of the self (Steele 1988). Messages that threaten the self may arouse defensiveness, which may prompt individuals to attempt to restore their self-image by denying that they are at risk and in need of modifying their behaviour (Sherman et al. 2000).

Self-affirmation may reduce perceptions of threat associated with health information, reduce individuals' avoidance of threatening information and, moreover, increase acceptance of this kind of information or feedback (Harris and Epton 2009; Howell and Shepperd 2012). Receiving positive feedback from others is an example of self-affirmation techniques. Sherman et al. (2000) suggest that employing self-affirmation techniques should be a part of a health campaign's content to increase the effectiveness of health information (Van Koningsbruggen and Das 2009).

Self-efficacy can be promoted through self-affirmation. According to Rimal (2001), self-efficacy determines whether an individual's perception of health risk translates into healthier behaviour and leads to seeking information on the health topic. Individuals who are aware of their health risk, but whose self-efficacy is low, may end up avoiding information related to the health topic. Self-efficacy is also crucial in determining whether fear appeals will motivate individuals to change their behaviour.

According to Case et al. (2005), avoidance is often seen as purposeful rejection of information. High levels of fear may easily inhibit persuasion through processes of denial and defensive avoidance (Ruiter et al. 2001), especially when self-efficacy is low (Witte et al. 2001). An increase in fear in health messages increases health behaviour intentions among older adults but reduces them among young adults (Keller and Lehmann 2008). In fact, the severity of the threat in fear appeal has been under study for many years. Witte and Allen (2000) conclude in their review that the greatest behaviour change is achieved by combining strong fear appeal messages with high self-efficacy messages. Moreover, strong fear appeals with low-efficacy messages produce the greatest levels of defensive responses. In other words, fear appears to be a great motivator as long as individuals believe they are able to protect themselves from the threat. Moreover, according to Ruiter et al. (2001), the personal relevance of health threats should be highlighted and self-efficacy bolstered. Emphasizing the severity of outcomes following risk behaviour however does not appear to be as important.

Methods and data collection

The empirical study was carried out in a setting provided by a physical activity promotion and type 2 diabetes prevention intervention trial (PreDiabEx). The trial was conducted under the auspices of health promotion and type 2 diabetes prevention programmes. The setting was Northern Finland, the University of Oulu (Medical Technology, Public Health Science and Physiology) and the Oulu Deaconess Institute. The trial lasted three months at the beginning of 2010. The data reported in this paper were collected through a questionnaire survey among pre-diabetic individuals after the trial. Objective physical measurements of their health status were conducted before and after the trial.

PreDiabEx intervention trial

Study subjects were recruited in the autumn of 2009 from outpatient diabetes clinics in the Oulu Deaconess Hospital and the City of Oulu. Of the 113 subjects screened with oral glucose tolerance or impaired glucose tolerance tests, seventy-eight fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate in the study. At the baseline seventy-two of them took part in the trial. The protocol of the trial was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Northern Ostrobothnia Hospital District. All the study participants gave written consent for participating in PreDiabEx. The trial registration number was NCT01649219 (clinicaltrial.gov).

In the intervention trial the participants were randomised into control and intervention groups by using a block design. Age and sex were chosen as the randomisation blocks (or strata) since they affect glucose balance the most. Computer-generated random numbers were used in the randomisation. The intervention group received structured exercise training and the control group were asked to continue their way of life as usual. Structured exercise training consisted of walking indoors three times per week for fifty minutes at a speed of two - four km/h, with ten minutes of warming up and stretching supervised by an athletic instructor.

Three participants withdrew from the trial (two from the intervention group, one from the control group). The survey was conducted after the trial in May-June 2010 at the same time as the physiological measurements were conducted. The responses were collected by nurse researchers from Oulu Deaconess Institute who helped the participants fill in the questionnaires, if necessary. Researchers from the Information Studies department designed and administered the surveys and analysed the data. Aerobic fitness was measured by an exercise physiologist and weight, height and blood glucose levels were measured by the nurse researchers. All participants were treated equally, regardless of whether they belonged to the intervention group or the control group.

Of the seventy-two original participants, sixty-eight responded to the survey; a response rate of 94.4%. The different questions in the questionnaire and the different objective measurements had somewhat different response or participation rates. In the beginning of the trial seventy-two participants and in the end sixty-nine took part in the glucose measurements. Aerobic fitness was measured for sixty-seven in the beginning and for sixty-four in the end, and the corresponding figures for weight and height measurements were sixty-nine and sixty-four.

Data collection

Previous questionnaires appearing in literature were reviewed, but suitable validated questionnaire instruments were not found. The survey questions were formulated to address individuals' health information behaviour and particularly their reception of the two message strategies. Three statements using fear appeal in relation to type 2 diabetes were presented to the participants. The statements were based on the ways an individual can respond to threatening information or mental images related to a disease. It was assumed that individuals are able to recall their reaction to threatening information or mental images related to type 2 diabetes. Their agreement with the statements was evaluated with a four-point Likert scale (strongly agree, moderately agree, moderately disagree, strongly disagree). 'Not sure' was also an option.

In addition, the participants were given five examples of feedback messages representing descriptive (factual), evaluative, ipsative, normative and theoretically driven message tactics. The messages presented by Hawkins et al. (2008) were applied in the design. The messages were designed to present a realistic situation for the participants and to imitate tailored feedback messages by summarising typical information about the individual's exercise behaviour and attempts to promote physical activity. Participants were asked to choose the message that would have the most motivating effect on them. The descriptive (factual) feedback was phrased as, 'This week you have burned 1200 kcal by attending moderate exercise' and the evaluative feedback was, 'This week you have attended a lot of moderate exercise. It has been beneficial to your health.' The ipsative (or self-comparison) feedback was phrased as, 'This week you have consumed more calories than last week through moderate exercise.' and the normative feedback was, 'You have attended moderate exercise on three days this week. That is more than Finnish people of your age exercise, on average.' The theoretically driven feedback alternative was stated as follows: 'This week you have attended moderate exercise on three days. That has been beneficial to your health, because according to general guidelines, moderate exercise can prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes.' The participants were also able to choose the 'I am not sure' option. The participants were further asked how strongly they agreed with the statements constructed in terms of the assumptions on which the three selected feedback message tactics were based, using a four-point Likert scale with a 'Not sure' option. For example, it can be assumed that individuals who prefer their behaviour to be compared with that of their peers would prefer messages based on the normative feedback message tactic.

Objective measurements of the individuals' physical health status were conducted. In this study, improvement in these measurements was seen as an improvement in health status. The Body mass index (BMI) of participants was used as an estimate of body fat percentage in body composition as follows: normal (from 18.5 to 24.9), overweight (from 25 to 30), obese classification I (from 30.1 to 34.9), II (from 35 to 40) and III (over 40).

Maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) was measured by an indirect submaximal oxygen uptake test on a bicycle ergometer that records heart rate. Maximal oxygen uptake reflects the condition of the cardiorespiratory system and the level of physical fitness, and it is reported relative to a person's weight (ml/kg/min). Because sex and age affect Maximal oxygen uptake values, a fitness classification by Shvartz and Reibold (1990) was used to compare the individual fitness test results on a seven-point Likert scale (very poor-excellent).

Abnormally high levels of blood glucose are encountered in pre-diabetic individuals. Fasting blood glucose (FBG) level is the most commonly used indicator of glucose homeostasis and it was determined from all the study participants. Fasting blood glucose levels were measured after an eight to ten hour fast and analysed according to the World Health Organization's diagnostic classification (World Health Organization 1999).

Data analysis

The differences in perceptions of fear appeal and preferences for a feedback message strategy between sexs and between those who were born in and before, or after 1950 were studied. The year 1950 was chosen because it divided the participants into two almost equally sized groups (those born in or before 1950 and those born after 1950). In 2010 those born in 1950 were 60 years old.

The survey data were studied in relation to changes in the participants' fitness, body mass index and fasting blood glucose classifications during the three months. When statistically testing the differences between groups, those who had improved their classifications formed one group and those with classifications which were impaired or the same as before the trial formed the other group.

We wanted to study the differences between those who had improved their physical health status and those who had not. In the analysis the participants were divided into those who improved their health status and those who did not, independent of their belonging to the intervention group or control group.

Statistical analysis with SPSS Statistics included calculation of distributions, dependence analysis using cross-tabulation, Fisher's exact test (2-sided) and a statistical hypothesis test to assess group differences using an independent-sample exact Mann-Whitney U test (two-tailed). For the Mann-Whitney U test the 'not sure' alternative was ignored. Non-parametric tests were used because of the skewed distributions and small number of participants. The values of Fisher's exact test and the Mann-Whitney test are reported when the values of statistical probability (p) were statistically significant (< 0.05). In the Mann-Whitney test the Z-value related to standardised test statistics is reported.

Results

The results section presents the background information of the participants and the results related to the fear appeal message strategy and the five feedback message tactics. Finally, the key results are summarised.

Background information

Of the sixty-nine trial participants, 51 (74%) were women. The majority (n = 40, 58%) were sixty years or older (born in 1950 or before) and as many were retired. Almost 80% were married or living with a partner and over half (n = 39, 56%) had only primary or lower secondary level education. 24% had completed secondary education and about 20% had a higher education. The levels of education were lower for those over sixty years old, which is in line with the distribution of the Finnish population (Kumpulainen 2009). One-fifth of the participants had a fitness classification of very poor or poor (19%), for 23 (36%) it was fair or average and for 29 (45%) it was good, very good or excellent at the end of the trial. Fitness classification had improved for 40 (63%) participants compared with the beginning of the trial. Almost all were overweight (n = 24, 38%) or obese (n = 34, 52%), but the body mass index classification had improved for 26 (41%) participants in comparison with their classification before the three month trial. 39 (57%) participants had normal fasting blood glucose values, 22 (32%) had impaired values and 8 (12%) had diabetic values. This classification had improved for 25 (36%) participants. (See also Enwald et al. 2012.)

Fear appeal message strategy

The participants were asked whether "information related to diabetes raises fears " 16 (25%) strongly and 15 (23%) moderately disagreed, 4 (6%) were not sure, 25 (39%) moderately and 4 (6%) strongly agreed. Men were more likely to answer (11/17, 65%) "moderately or strongly agree " than women (18/47, 38%), the majority of whom disagreed with the statement (26/47, 55%). However, this difference was not statistically significant. No statistically significant results were observed according to age (born before or in 1950 or after 1950) or health status. Possible improvements in health status did not result in statistically significant differences in the perception of whether information related to diabetes raises fears.

The participants were asked whether 'threatening mental images about the onset of diabetes are able to promote physical activity and eating behaviour'. Two participants (3%) strongly and 8 (12%) moderately disagreed, 3 (5%) were not sure, and 32 (49%) moderately and 20 (31%) strongly agreed. All of those who disagreed with the statement were women, but this result was not statistically significant. No statistically significant differences were observed according to age and health status or according to whether the participants' fitness classification had improved during the trial.

Those who did improve their body mass index classification were more likely to agree (22/24, 92%) with the statement than those whose classification did not improve (27/37, 73%). This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.017, Mann-Whitney test). Improvement in fasting blood glucose levels during the trial did not result in a statistically significant difference in perception of the promotional ability of threatening mental images.

In addition, participants were asked whether they agreed with the statement "threatening mental images about the onset of diabetes dishearten me ". Twenty-four of the 65 participants (37%) strongly disagreed and 20 (31%) moderately disagreed, 10 (15%) were not sure, and 9 (14%) moderately agreed and 2 (3%) agreed strongly. No statistically significant differences were observed according to sex, age, physical health status or its improvement.

To summarise the statements related to a fear appeal message strategy, the results of the Mann-Whitney test are presented in Table 1. The only statistically significant result in the Mann-Whitney exact U test was observed when the participants whose body mass index classification had improved and those whose classification had not improved were compared in relation to their perceptions of whether threatening mental images about the onset of diabetes are able to promote healthier behaviour. No statistically significant results were observed in Fisher's exact test.

| "Information related to diabetes raises fear " | "Threatening mental images about the onset of diabetes are able to promote physical activity and eating behaviour" | "Threatening mental images about the onset of diabetes dishearten me" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | Exact p | Z | Exact p | Z | Exact p | |

| Sex * | -1.49 | N.S. | -0.89 | N.S. | -0.10 | N.S. |

| Age ** | -0.09 | N.S. | -0.90 | N.S. | -0.63 | N.S. |

| Change in physical fitness *** | -0.06 | N.S. | -0.87 | N.S. | -0.84 | N.S. |

| Change in body mass index *** | -0.86 | N.S. | -2.38 | 0.019 | -0.80 | N.S. |

| Change in fasting blood glucose level *** | -1.11 | N.S. | -1.19 | N.S. | -0.90 | N.S. |

| N.S. = not significant; * men or women; ** born in 1950 or before or born after 1950; *** improved or no change or impaired. | ||||||

Preference for different feedback message tactics

The participants were given five examples of feedback messages about the benefits of increasing the amount of exercise. They were asked to choose which one would be the most motivating for them. The messages considered the most motivating were the theoretically driven feedback, chosen by 32 participants (52%), the evaluative feedback, chosen by 11 (18%), and the normative feedback, chosen by 10 (16%).

| Feedback message tactic | All participants n (%) |

Sex | Age | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| women n (%) |

men n (%) |

born in or before 1950 n (%) |

born after 1950 n (%) |

||

| Theoretically-driven | 32/62 (52%) | 21/46 (46%) | 11/16 (69%) | 20/35 (57%) | 11/25 (44%) |

| Evaluative | 11/62 (18%) | 10/46 (22%) | 1/16 (6%) | 4/35 (11%) | 6/25 (24%) |

| Normative | 10/62 (16%) | 8/46 (17%) | 2/16 (12%) | 5/35 (14%) | 5/25 (20%) |

The analysis of this question focused on the differences between those who had chosen messages based on one of the three most popular feedback message tactics. Two-thirds of the men (11/16, 69%) found the theoretically driven feedback to be most motivating compared with under half (21/46, 46%) of the women. Theoretically driven feedback was preferred more by older individuals (born in or before 1950). Women chose the evaluative alternative (10/46, 22%) more often than men (1/16, 6%). (See Table 2.)

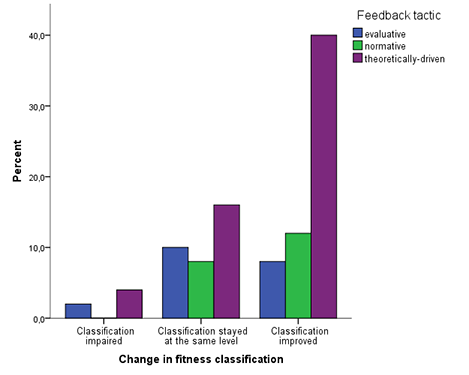

There were no differences regarding the participants' fitness, body mass index or fasting blood glucose classifications or whether or not the classifications had improved during the trial. The differences according to the change in fitness classification during the trial are shown in Figure 2.

The analysis shows that most of those who chose the theoretically driven (20/30, 67%) or normative (6/10, 60%) feedback had succeeded in improving their fitness classification in comparison with those who chose the evaluative feedback (4/10, 40%), because for half of them their fitness classification had stayed at the same level. On the other hand, over half of those with an improved fitness classification found the theoretically driven feedback most motivating (20/35, 57%) when compared with those whose classification did not change (8/20, 40%).

Ipsative and normative feedback message tactics

The ipsative feedback message tactic is based on providing information on how a person is performing compared with his own previous results. Most participants agreed with the argument related to ipsative comparison 'information about the improvement of my physical fitness motivates me'. No one disagreed, 2 (3%) participants were not sure, 24 (36%) moderately agreed and 41 (61%) strongly agreed. There were no statistically significant differences observed in the groups divided according to sex, age or physical health status or a change in status during the trial.

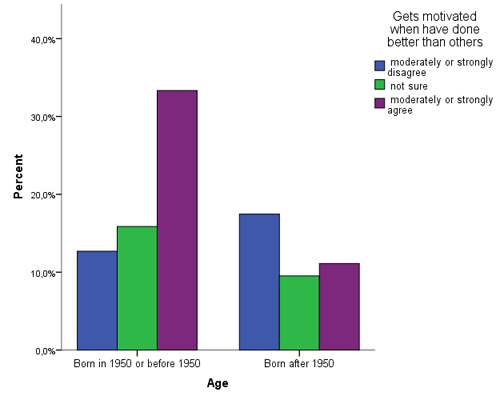

Normative feedback is based on normative comparison. Preference for normative comparison was examined with a positively phrased statement "I get motivated when I have done better than others". 12 (18%) strongly disagreed, 7 (10%) moderately disagreed, 17 (25%) were not sure, 22 (33%) agreed moderately and 9 (14%) agreed strongly. No difference was observed according to sex. More of the participants born after 1950 disagreed with the statement (11/26, 46%) than did the older participants (8/39, 21%). This observation related to age is statistically significant (p = 0.027, Mann-Whitney test) (See Figure 3).

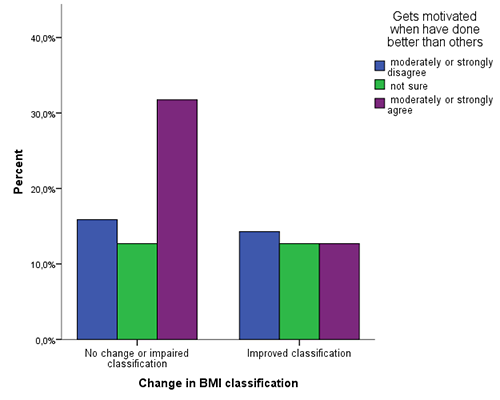

No statistically significant differences were observed regarding fitness classification, change in fitness classification during the trial or body mass index classification. On the contrary, the participants whose body mass index classification stayed the same or was impaired, were more likely to agree with the normative statement. This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.022, Mann-Whitney test) (See Figure 4).

When fasting blood glucose classifications and preferences for the normative statement where cross-tabulated, those with the classification 'impaired' had chosen the alternative 'not sure' more often (9/21, 43%) than those in the classifications 'normal' (7/39, 18%) or 'type 2 diabetes' (1/7, 14%). In the classifications 'normal' (22/39, 56%) and 'type 2 diabetes' (4/7, 57%), most participants agreed with the normative statement (p = 0.008, Fisher's exact test). No statistically significant difference was noted in relation to improvement in fasting blood glucose classification during the trial.

Theoretically driven feedback message tactic

Preference for the theoretically driven feedback tactic was investigated by using the statement 'I don't desire scientific facts about health information'. 23 participants (34%) strongly disagreed and 22 (33%) moderately disagreed, 9 (13%) were not sure, 10 (15%) moderately agreed and 3 (5%) strongly agreed with the statement. No difference regarding sex or age was observed. No notable differences were observed regarding physical health status and its improvement.

To summarise, the results of the Mann-Whitney test are presented in Table 3. The only statistically significant result of Fisher's exact test was observed when fasting blood glucose classifications and perceptions of a normative comparison were cross-tabulated.

| Ipsative feedback message tactic | Normative feedback message tactic | Theoretically driven feedback message tactic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | Exact p | Z | Exact p | Z | Exact p | |

| Sex * | -1.21 | N.S. | -0.64 | N.S. | -0.08 | N.S. |

| Age ** | -0.12 | N.S. | -2.21 | 0.026 | -0.17 | N.S. |

| Change in physical fitness *** | -0.62 | N.S. | -0.50 | N.S. | -0.86 | N.S. |

| Change in body mass index *** | -0.88 | N.S. | -2.29 | 0.019 | -0.51 | N.S. |

| Change in fasting blood glucose level *** | -0.89 | N.S. | -0.02 | N.S. | -1.24 | N.S. |

| N.S. = not significant; * men or women; ** born in 1950 or before or born after 1950; *** improved or no change or impaired | ||||||

Summary of key findings

The most significant results are summarised as follows. In connection with the fear appeal message strategy, most of the participants (81%) agreed with the statement 'threatening mental images about the onset of diabetes are able to promote physical activity and eating behaviour'. Those who did improve their body mass index classification were more likely to agree (22/24, 92%) with the statement than those whose classification did not improve (27/37, 73%) (p = .017, Mann-Whitney test). Most of the participants (68%) disagreed with the statement 'threatening mental images about the onset of diabetes dishearten me'.

In connection with the feedback message strategy, when given 5 feedback message examples of the benefits of increasing the amount of exercise, the theoretically driven feedback, chosen by 32 participants (52%), the evaluative feedback, chosen by 11 (18%), and the normative feedback, chosen by 10 (16%) were considered the most motivating. Men and participants aged sixty or older preferred the theoretically driven alternative more than the others. More of those who chose the theoretically driven (20/30, 67%) or normative (6/10, 60%) feedback had succeeded in improving their fitness classification than those who chose the evaluative feedback (4/10, 40%).

The responses were evenly distributed for the statement 'I get motivated when I have done better than others'. Age was one factor affecting the preference for the normative feedback message tactic, as more of the participants born after 1950 disagreed with the statement (11/26, 46%) than did the older participants (8/39, 21%) (p = 0.027, Mann-Whitney test). The participants whose body mass index classification stayed the same or was impaired were more likely to agree with the normative statement (p = 0.022, Mann-Whitney test). In the fasting blood glucose classifications "normal" (22/39, 56%) and "type 2 diabetes" (4/7, 57%), the participants were more likely to agree with the normative statement (p = .008, Fisher's exact test).

Discussion

This study contributes to Information Studies from the perspective of information behaviour in the context of health promotion. The study aimed at increasing understanding about the information users and their individual characteristics related to information use, especially from the perspective of information reception. The objective of the study was to identify individual differences in perceptions of a fear appeal message strategy and preferences for feedback message tactics as such, and also in relation to sex, age, physiological health status (identified by objective measurements of physical fitness, body composition and glucose homeostasis) and changes in health status during the trial. This methodologically novel approach utilises and combines data gathered by subjective and objective research methods.

The results indicate some statistically significant differences between pre-diabetic individuals' perceptions of and preferences for two investigated message strategies in relation to socio-demographic factors and health statuses. Body mass index was an important indicator for reception of both message strategies and additionally, age and fasting blood glucose levels were associated with preference for the normative feedback message tactic.

The most significant result related to the fear appeal message strategy is that the participants who succeeded in losing weight during the three month intervention trial were significantly more likely to believe that threatening mental images about the onset of diabetes are able to promote their physical activity and improve their eating behaviour. This indicates that individuals with successful experiences-observed as weight loss-may respond in a more flexible manner to threatening information than those who do not succeed in improving their health status by losing weight. An explanation for this result could be that by participating in the PreDiabEx intervention trial some of the participants had improved not only their self-efficacy but also their self-affirmation. According to Bandura (1977), successful performance of target behaviour increases self-efficacy, and on the other hand self-efficacy has been stated to predict exercise behaviour (Rimal 2001). In addition, Pálsdóttir (2008) suggests that there may be a relationship between self-efficacy, health behaviour and health information behaviour. Increasing self-efficacy through self-affirmation may help to eliminate information avoidance (Howell and Shepperd 2012). Self-affirmation allows individuals to respond in a more flexible manner to threatening health information which is phrased in a manner that is not too frightening to them (Sherman and Cohen 2002).

The results of this study show that age and physical health status, according to body mass index and fasting blood glucose levels, were found to be statistically significant differentiating factors related to preference for feedback message tactics. Interestingly, the study participants who did not lose weight during the trial perceived the normative comparison as motivational. The association between fasting blood glucose and preference for a normative feedback message tactic was also statistically significant, as those with a normal glucose value and those with a diabetic value were more likely to prefer a normative comparison than those with an impaired glucose value. In addition, elderly individuals felt that the normative comparison motivated them. In a study by Williamson (2005), older individuals did not want a lot of technical or medical details in health information. However, this finding is not supported by this study, where in responses to the statement 'I don't desire scientific facts about health information', the difference according to age was not significant. The statements representing ipsative, normative and theoretically driven feedback message tactics were phrased in a positive manner. Negatively phrased statements on the same topic may have produced different results.

Over half of the participants, when asked to choose the most motivating exercise-related feedback, chose the theoretically driven message. Those who chose the message based on the theoretically driven or normative message tactic had succeeded better in improving their physical fitness during the trial than those who chose the evaluative alternative. Correspondingly, those who had improved their physical fitness were more likely to choose the theoretically driven message alternative. It has to be taken into account that the five feedback message examples representing feedback message tactics were phrased in different manners; for example, the descriptive (factual) alternative included numbers (amount of kcal) while the others did not. This might have had an effect on the results.

It has been stated that sex-related constructs are likely to be important variables in information behaviour (Urquhart and Yeoman 2010; Ek et al. 2011). In this study some differences between sexes were observed, but they were not statistically significant. All ten participants who stated that threatening mental images about the onset of diabetes do not promote their health behaviour were women. Men were more likely to prefer the message based on the theoretically driven feedback message tactic and women were more likely to prefer the message based on the evaluative feedback message tactic. Proportionally more men felt that information related to diabetes raises fears.

The practical implications of this study can be a contribution to healthcare providers in the planning of tailored health communication. The study highlights the importance of investigating perceptions of a fear appeal message strategy and preferences for feedback message tactics among high-relevance individuals. Different kinds of health messages could be preferred by those who have succeeded in improving their health status and those who have not yet succeeded. This study elucidates that age and physical health status-particularly objectively measured change in body mass and blood glucose levels-are factors to be taken into account when applying feedback and fear appeal message strategies in tailoring health information among individuals at risk of contracting type 2 diabetes.

Fear appeal studies have been conducted with individual difference variables, but the results of these studies have been inconclusive (Witte & Allen 2000; Kok et al. 2004). Moreover, the fear appeal message strategy needs to be used with caution, especially for those who have not yet succeeded in improving their health behaviour and might have low self-affirmation. Or, as Witte and Allen (2000) suggest, a message with strong fear appeal should be combined with high-efficacy messages which support individuals' belief that they are able to protect themselves from the threat. These messages could include elements constructed by using, for example, the normative and ipsative feedback message tactics. Moreover, the results could be elaborated further to promote health by applying them to general health behaviour change models and applications of these models as behaviour change support systems (Oinas-Kukkonen in press).

Conclusion

The novel methodological approach explored in this study provides a useful basis for increasing understanding about users of health information and their individual characteristics from the perspective of reception of information. Generally, fear appeal as a message strategy has been a contradictory subject in health promotion. In addition, feedback as a message strategy has been emphasised and utilised as an important factor in promoting health behaviour change. This study provides more detailed information about individual factors affecting reception of information. Age and improvement in health status-observed as weight loss-stand out as factors in which individual differences appear to have an influence on the reception of the fear appeal and feedback message strategies.

There are limitations in the results of this explorative study. The study relies partly on self-reported survey data. The sample size is relatively small. Thus, the results of the statistical tests are only indicative. The study participants were already motivated to participate in the trial and they were aware of their high risk for type 2 diabetes. Repetition is warranted. Furthermore, the participants were mostly women over the age of sixty, and the approach of the study is exploratory, as all the topics were assessed with only a few questions.

This study did not examine individual differences according to educational level. Furthermore, improvement in health status may result in an increase in an individual's self-efficacy. The results on the individual factors affecting the preference for feedback message tactics have been elaborated further in a population-based survey among young Finnish men. The focus of that study was on young men's preferences for ipsative, normative and theoretically driven feedback message tactics in relation to their education, stage of change, self-reported physical activity, exercise self-efficacy and health status, measured by physiological measurements (See Hirvonen et al. 2012). Educational level and self-efficacy, in addition to objectively measured factors, in relation to reception of information and information use, deserve further attention in the context of health communication.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland and the Finnish Diabetes Foundation.

About the authors

Heidi Enwald is a PhD Candidate in Information Studies, Faculty of Humanities, University of Oulu, Finland. She has a Master´s degree in Information Studies and in Biochemistry from University of Oulu. Her main research interests are tailoring health information and health information behaviour. She can be contacted at: heidi.enwald@oulu.fi

Terttu Kortelainen, PhD, is University Lecturer of Information Studies at the University of Oulu, Finland. Her research interests are in informetric research, social media, and in the evaluation of libraries. She has also supervised research projects focusing on usability of web services and evaluation of libraries. Her publications consist of four study books, a doctoral thesis, articles on informetrics, and articles on the study projects of the department. She is member of the Advisory Committee of the Finnish Social Science Data Archive and the publication board of the Finnish Information Studies publication series. She can be contacted at: terttu.kortelainen@oulu.fi

Juhani Leppäluoto, PhD, MD, h.c. is a retired Physiology Professor at the University of Oulu, Finland, and continues his research at the University. Leppaluoto´s research area is endocrinology and he has studied physiological characters of thyroid, adrenal, pituitary, hypothalamic, pineal, heart and pancreatic hormones. For last years he has participated into two clinical intervention studies using motion sensors to record objectively health effects of exercise on bone mass and cardiovascular risk factors in premenopausal women and on glucose, insulin and lipids in subjects having abnormal blood glucose concentrations (PreDiabedEx). He can be contacted at: juhani.leppaluoto@oulu.fi

Sirkka Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi MD, PhD, is Professor and head of institute at Institute of Health Sciences, University of Oulu, Finland. She can be contacted at: skk@sun3.oulu.fi

Timo Jämsä is Professor in Medical Technology at the University of Oulu, Finland. He has over 30 years of experience in research and education in biomedical engineering and medical technology. His areas of interest include biomechanics, medical imaging, eHealth, and technologies for ambient assisted living. He can be contacted at: timo.jamsa@oulu.fi

Harri Oinas-Kukkonen PhD, is Professor of Information Systems at the University of Oulu, Finland. His current research interests within informatics, information systems and human-computer interaction include persuasive design, behaviour change, social and humanized web, and zero-to-one innovation. He has been listed among the hundred most influential information technology experts in the country, and a key person to whom companies should talk to when developing their strategies for web-based services. In 2005, he was awarded The Outstanding Young Person of Finland award by the Junior Chamber of Commerce for his achievements in helping industrial companies to improve their web usability. He can be contacted at: harri.oinas-kukkonen@oulu.fi

Karl-Heinz Herzig MD, PhD, is Professor in the Department of Physiology, Institute of Biomedicine, University of Oulu, Finland. He has also been working as a group leader in A.I. Virtanen Institute, Department of Biotechnology and Molecular Medicine, University of Kuopio, Finland. He can be contacted at: karl-heinz.herzig@oulu.fi

Maija-Leena Huotari PhD, is Professor of Information Studies at the Faculty of Humanities, the University of Oulu, Finland. She was the Principal Investigator of the Academy of Finland funded project Health Information Practice and Its Impact in 2008-2012. She can be contacted at: maija-leena.huotari@oulu.fi