Analysing information behaviour in structured service encounters: a case of call centre operations

Yung-Hsiu Lin

Department of Information Management, Ta-Hwa Institute of Technology, Taiwan

Rong-Rong Chen

Service Systems Technology Center, Industrial Technology Research Institute, Taiwan

Her-Kun Chang

Department of Information Management, Chang Gung University, Taiwan

Introduction

Information behaviour is a crucial activity for service agents when conducting daily service encounters (Spink 2010). Service encounter is a dynamic business process that requires the agents to interact directly with customers to resolve their problems (Bradley et al. 2010). The agents may response to the problems intuitively with their existing knowledge and experiences or they may seek various information sources and use those to resolve the customers' problem situations (Wilson 2000). Such agent information behaviour can have substantially impact on customer satisfaction during service encounters and may further influence customer loyalty toward a service firm (Bitner et al. 1990). Information behaviour is a complex human activity consisting of purposive and non-purposive actions that can be described as an individual's instinct and affected by external factors such as organizational tasks or customer problem situations (Spink and Cole 2006; Spink 2010). analysing agents' information behaviour in the context of service encounters can help service managers apply theoretical principles from information behaviour studies to figure out practical managerial situations in interests (Sonnenwald and Pierce 2000; Sonnenwald et al. 2008; Paul and Reddy 2010). Service organizations are paying more attention to the management of agent information behaviour (Reddy and Spence 2008). However, the description of agent information behaviour in the context of service encounters and the design of supporting mechanisms to facilitate such behaviour in real world situations remains poorly understood (Byström and Hansen 2005; Chesbrough and Spohrer 2006).

Service encounters can be defined as a period of time in which service agents directly interact with customers (Shostack 1987). Service encounters represent the moment of truth for a service firm in that agent's business knowledge and operational skills can determine the achievement of a service (Noone et al. 2009). Business knowledge consists of task information in relation to a specific domain, problem encountered, and problem-solving skills (Byström and Järvelin 1995). The operational skills include behaviour on handling above mentioned information, such as identifying information needs, seeking information sources, searching for problem information, and using problem-solving information to resolve problems that stimulated the information needs (Spink 2010). Such operational skills can be enhanced through collaborative efforts among agents and supported with organizational settings, including cultural and social factors to facilitate developments of required information behaviour (Polanyi 1958; Sonnenwald 1999; Sonnenwald et al. 2008). Moreover, advanced information technologies offer opportunities for service managers to collect and analyse agents' operational details. This operational information can then be used to design managerial interventions to assist agents in handling their information problems (Spohrer and Maglio 2008).

This study is intended to advance our understanding of agent information behaviour in practical service encounters and to help agents with their information problems both within service encounters and around organizational contexts. The general research question focuses on agent information behaviour, including information need, seeking, search, and use that influences an agent's knowledge on handling domain, problem, and problem-solving information relevant to certain organizational tasks. Specifically, this study explores the following questions:

- Can we describe information behaviour in the context of practical service encounters?

- Can we facilitate agent information behaviour toward the improvements of organizational performance?

A real world call centre was used as an example in this study to describe and analyse agent information behaviour in the context of service encounters. The call processing conducted by first line agents was designated as the research subject for information behaviour studying. Two performance indicators were selected to measure agent behaviour changes in relation to the call processing activity. A triangulation approach was taken (Jick 1979; Bryman 2006), based on the theoretical framework, to understand the complexity of agent information behaviour and discover the opportunities for organizational improvements from information behaviour perspectives.

Theoretical framework

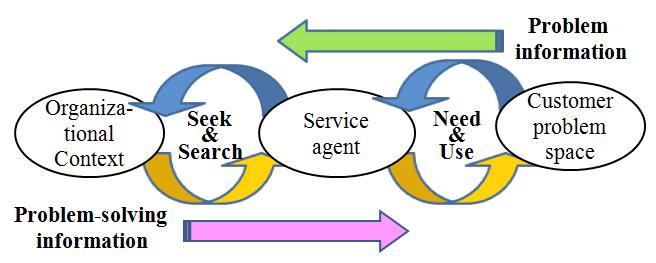

Agent information behaviour in the context of service encounters is complex and dynamic (Byström and Hansen 2005) so that even experienced service agents cannot tell in detail how they handle required information when interacting with customers to solve their problems (Reddy and Spence 2008). The interactions consist of agent information behaviour including internal instinctive movements (Spink 2010), such as information forging and sense-making (Dervin 1992; Kuhlthau 2004) and external actions, such as information seeking and use. They process domain information, problem information, and problem-solving information to resolve the problems encountered in relation to organizational tasks (Byström and Järvelin 1995; Wilson 2005; Johnson 2009). The agent's internal movements are difficult to observe and articulate during service encounters. However, the internal behaviour can be influenced, in practical business settings, by explicit objectives such as organizational tasks (Byström and Hansen 2005; Wilson 2005; Spink 2010). For describing and analysing information behaviour in real world service encounters, a theoretical framework was proposed to represent our understanding; this was used as a starting point for the research. Figure 1 depicts the framework of agent information behaviour in the context of service encounters.

The framework integrates theoretical principles from information behaviour studies (Byström and Hansen 2005; Wilson 2005; Spink 2010) with the context of service encounters (Shostack 1987). The framework consists of three elements: service agent, customer problem space and organizational context. The elements are connected with actions of information behaviour including information need, seeking external sources, searching existing knowledge bases, and use (Spink 2010). During service encounters, a service agent interacts with customers who may have various problems emerged from customer problem space. The agent should identify problem information which can create information need and stimulate the agent to use existing knowledge to resolve the problem (Dervin 1992; Kuhlthau2004). The information need may not be fulfilled at first encountered and that can motivate the agent to seek proper information sources in the organizational context and merge problem-solving information with her knowledge base (Sonnenwald 1999). The two action cycles in the framework connect an agent with customer problem space and organizational context that can be used to describe how an agent handles information problems under organizational tasks.

Background of the call centre

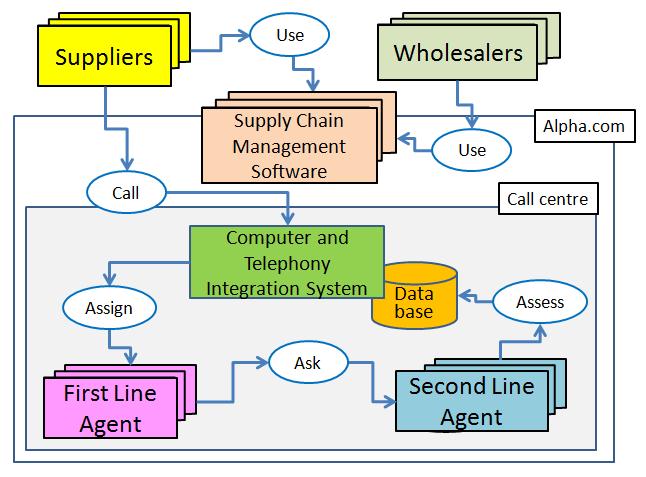

Alpha.com is a medium-sized software company developing wholesaler supply chain management software and the business runs as an application service provider, renting developed software to various wholesalers and supporting their supplier relationships management. The application service provider business model is based on building a version of software that can be rented to different companies with limited customization and benefits both developer and renters in terms of development and maintenance costs. In this case, wholesalers rent supply chain management software from Alpha.com to maintain business relationships with suppliers. The suppliers then use this software to establish business relationships with wholesalers. The suppliers have different skill levels when using the software, for instance, there is variation in their understanding of business rules embedded in the software and in their computer literacy. These suppliers require a call centre service from wholesalers that can promptly resolve their operational problems over the phone. Alpha.com established a professional call centre to manage the call centre services outsourced from wholesalers. During the last decade, the call centre supported over 70 sets of supply chain management software for different wholesalers and serviced over 70,000 suppliers. Currently, the call centre maintains approximately 30 sets of the active software, about 20,000 suppliers, and an average of 8,000 incoming calls monthly. To abstract complex business relationships from above description and identify major entities related to service encounter operations, an entity-relationship description method was used to depict the entities and their relationship in this call centre (Chen 1976; Jacobson et al. 1992). Figure 2 illustrates the operational architecture of the call centre.

The call centre operational architecture comprise six entities as illustrated in Figure 2, including wholesalers, suppliers, supply chain management software, first line agent, second line agent, and a computer and telephony integration system. The system is the operational backbone of the call centre supporting routine business processes and recording agent operational details. The relationships, illustrated via oval shape in Figure 2, describe the actions between two entities. Wholesalers rent supply chain management software from Alpha.com to maintain business relationships with suppliers. The suppliers then use this software to establish business relationships with wholesalers. The suppliers register to use certain sets of software and then can request assistance from the call centre whenever they encounter problems in using that software. The computer and telephony integration system receives an incoming call from suppliers, identifies those suppliers, assigns the call to an available first line agent, and records the details of how the service encounter is being handled. The first line agents can resolve incoming calls by themselves or request assistance from second line agents. The second line agents assume managerial rather than operational roles in the call centre. Specifically, they routinely evaluate first line agent operations and adjust operating rules with the computer and telephony integration system to improve organizational performance.

Method

This study took a triangulation approach (Jick 1979) to analyse agent information behaviour in the context of a call centre. The approach applied two research methods (field observations and interviews) and a behaviour intervention. The field observations and interviews were intended to understand the operations of call centre from a wider perspective and investigate agent information actions in the daily call processing operations. The behaviour intervention aimed to test whether agent information behaviour can be influenced with managerial efforts and to evaluate the design of the intervention from the perspectives of organizational performance improvements. The data were collected from various sources, including the agents observed, the managers interviewed, and the data retrieved from technical database, in order to advance our understanding on this complex human-involved social phenomenon (Spink and Cole 2006; Spohrer 2006) and enhance confidence in the research findings.

Participants

All first line agents (N = 7) were included as subjects in this study. This is a one group pre- and post-test study without control group. To secure the reliability of the findings, three second line agents and call centre managers participated in this study and collaborated with researchers on providing call centre service data, attending discussions, and designing the behaviour intervention. Technical experts of the computer and telephony integration system were also consulted when retrieving agent operational details from technical database. This study lasted for nine months from April 1 to December 31 2007.

Field observations and interviews

The field observations explored what information problems the first line agents need to manage in the service encounters. Three types of information (domain information, problem information, and problem-solving information) were defined in this call centre with three operational settings for in-depth observations. The first setting focused on domain information that first line agents can build up from organizational training. Researchers participated in a one-day training course with first line agents, to observe what domain information and operational skills the agents are taught. The second setting concentrated on problem information that first line agents need to identify from customer interactions. After oriented with call processing procedures by second line agents, researchers were organized to sit beside first line agents, equipped with earphones to listen and observe how agents get to understand customer problem descriptions, identify problem information, and use the computer and telephony integration system for further call processing. The third setting centred on problem-solving information that first line agents can seek from within the organization. Researchers took part in call centre social functions and observed interactions among agents for sharing problem-solving information and experiences when they were not on duty.

The interviews investigated how first line agents handle information problems in the context of service encounters both from individual and organizational perspectives. Researchers reviewed call centre organizational documents and conducted initial analyses of agent operational details from the technical database to assess the findings from their observations before the interviews. All first line agents, three second line agents, and one manager were interviewed. Open-ended questions were designed and asked either in formal meetings or informal conversations. The questions focused on the themes, such as how first line agents maintain their domain knowledge, how first line agents identify problem information from customer's descriptions, what information sources will first line agents seek for assistance. Two researchers were organized as a team in each interview, one for interacting with agents and one for taking notes. The notes were then edited and discussed with second line agents and managers of the call centre to ensure the reliability of findings and verify the understanding of researchers.

The theoretical framework depicted in Figure 1 indicates information flows both from customer problem space and organizational context that has been used in the field observations to identify information needs. Together with operational architecture of the call centre depicted in Figure 2, the information behaviour indicated in the framework was used in the interviews for analysing how first line agents handle required information.

Behaviour intervention

A behaviour intervention was designed to mobilize the cycle of information behaviour in service encounters (illustrated in Figure 3 in Results section). Since customer situations are varied, identification of customer problem descriptions in incoming calls can be difficult and result in delays in required time for call processing. Moreover, most real world problem-solving information cannot be articulated in detail, so establishing an information sharing culture is crucial to enable agents to share their experiences on solving customer problems. The culture creates an environment allowing agents to make sense about problem-solving information through a collaborative learning process. A keyword approach (Jaimes et al. 2003; Baker 2004; Kipp 2006) was used to encourage agents to outline customer problems by identifying keywords mentioned by customers within service encounters. The agents could then relate the keywords to problem information that existed in their knowledge base and trigger available problem-solving information which could be provided to the client. Where there was no relevant problem-solving information, agents would be motivated to seek and search for information in the organizational context area. The behaviour intervention has been administrated with managerial support and facilitated with informal community activities that can be described as a four-step procedure as follows.

Identify key words to describe customer problem space

Keywords mentioned by customers provide important clues that first line agents can use to identify problem information during service encounters. Agents are guided by the computer and telephony integration system in classifying customer problems into question types based on the problem information they identified. To support the agents in picturing customer situations and classifying their problems into proper question types, one second line agent was designated to prepare an initial set of keywords. One hundred recorded incoming calls were randomly selected from the technical database to provide a basis for selecting potential keywords. The second line agent listened to the conversations between customers and first line agents and wrote down the keywords mentioned by customers that she thought can best represent problems emerged from the customer problem space.

Discuss the identified key words with agents

The selected key words were first discussed by all second line agents to verify the representation of the key words. Second line agents are responsible for maintaining question types for different sets of rented software in the computer and telephony integration system, so designing proper classifications of question types can influence first line agent operational performance. A total of 120 key words were selected and a training program was organized for all first line agents to explain how to identify keywords through interacting with customers, and how to understand the relationship between the keywords and the problems in customer problem space.

Add an extra action in the service encounter area

Before wrapping up an incoming call, first line agents should log the details of how a call has been processed on a service form in the computer system. An extra action was designed to ask first line agents to input identified keywords into an empty column of the service form. This procedure might increase the call processing time for some agents. However, the required keyword input can motivate agent information seeking activities in service encounter area and relate customer problem descriptions to certain problem and problem-solving information.

Organize experience sharing functions in the service context area

Owing to the complexity of customer situations, first line agents may lack knowledge and experience in solving certain problems when they first encounter these problems. Two social functions were arranged to encourage information sharing in the organizational context. The first function involved second line agents being encouraged to discuss the keyword practices with the first line agent they were coaching; the second such function involved adding an experience sharing session for first line agents during each lunch break to motivate them to share experiences and seek problem-solving information in relation to the problems they encountered.

This behavioural intervention lasted for three months (June to August 2007). The keyword set was discussed and adjusted during this period. The first line agents may have adjusted their information behaviour to cope with this intervention. The behavioural changes of each first line agent can be too subtle to be clearly described, but the results of the behavioural changes can be identified using certain performance indicators recorded by the computer and telephony integration system.

Evaluation

Performance indicators are the reflection of agents' daily activities and can be obtained through the recorded data from the computer and telephony integrating system in the call centre. All first line agents were assumed to be motivated to excel at the indicators. Two performance indicators were selected to evaluate the effects of behaviour intervention. One is classified ratio, indicating the ratio of incoming calls that have been correctly classified into various question types other than the category of "Others". This can determine whether the keywords intervention can help agents to grasp problem information from customer descriptions. The other is required time, indicating the time required by agents for processing an incoming call. This is an overall performance indicator contributing by various purposive and non-purposive activities that can partially determine the effect of managerial efforts regarding agent information behaviour during the intervention.

The computer and telephony integrating system recorded details information of agents' daily activity in a relational database. All seven first line agents' call processing records were included in data analysis. We extracted two raw datasets from the database for further analysis. One, which serves as the baseline, covers two months period before the intervention (April to May 2007) and the other, which serves as the comparison, covers four months period following the intervention (September to December 2007). The comparison dataset was further divided into four subsets (the first month to the fourth month after intervention) to examine incremental effects of the intervention. A total of 27,677 call processing records were extracted. Within these records, we excluded the records which were not resolved within the first call resulting in 27,459 records for data analysis. Table 1 lists the numbers of call processing records before and after exclusion in each dataset. Wilcoxon signed ranks test in the statistical software SPSS was used to conduct tests before and after the intervention effects in relation to the two performance indicators. A 2-tailed p value <0.05 was considered significant in the test.

| Before intervention | After intervention | 1st month follow up | 2nd month follow up | 3rd month follow up | 4th month follow up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before exclusion | 9613 | 18064 | 4256 | 4910 | 4689 | 4209 |

| After exclusion | 9542 | 17917 | 4219 | 4869 | 4654 | 4175 |

Results

The results of this agent information behaviour study are provided below in the forms of description of information behaviour in the context of service encounters, qualitative narrative drawn from the field observation and interview data and quantitative analyses of the behaviour intervention.

Description of information behaviour in the context of service encounters

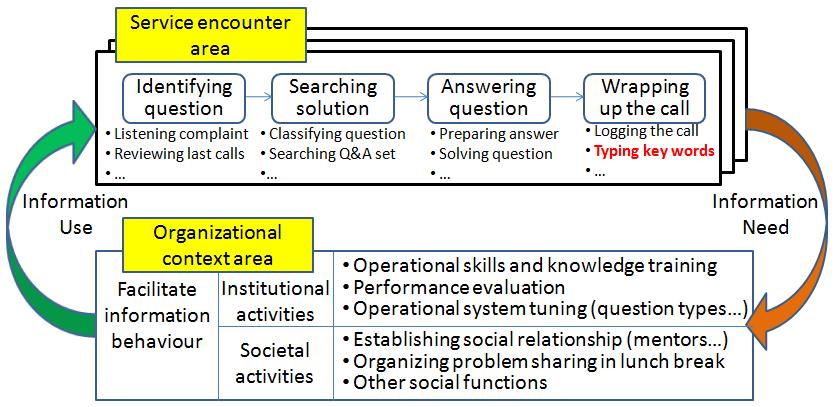

Based on the proposed theoretical framework, the researchers learned the complex social phenomenon of agent information behaviour about this call centre from the field observations and interviews. An operational model describing such phenomenon was developed to describe this specific case and served as a common picture between researchers and managers for further managerial discussions. Figure 3 is the model that illustrates cyclic information behaviour within two functional areas. The first is service encounter area that links service agent and customer problem space indicated in Figure 1. This functional area based on a problem-solving approach (Wilson 2000) describes a sequence of explicit tasks, including identifying problem, searching solution, answering problem, and wrapping up the call in service encounters. Customer problem space will activate the sequence and create information need for agents (Spink and Cole 2006). The sequence can be used as a guideline for first line agents such that each agent can develop their own information seeking strategies with different purposive and non-purposive activities. The second is organizational context area that connects a service agent with an organizational context. This functional area, based on sense-making and collaborative approaches (Kuhlthau 2004; Hertzum 2008; Reddy and Spence 2008; Sonnenwald et al. 2008), describes organizational and societal activities, such as formal training and informal communications in relation to information seeking and searching within an organizational context.

The call centre schedules work shifts for each agent so that each has chances to move between the two functional areas. Customer problems in the service encounter area might create information needs that motivate agents to seek and search problem-solving information from different sources in the organizational context area. Agents can then use the information found in the service encounter area to solve customer problems. The operational model indicated in Figure 3 describes a learning cycle for agents that can be used to analyse agent information behaviour and develop interventions to facilitate the behaviour. How to identify opportunities for development has attracted managerial attention in industries. Specifically, helping agents to quickly identify customer problems from problem information in the service encounter area and motivating agents to share problem-solving information in the organizational context are of interest of this study.

Thematic analysis of observation and interview

The findings from qualitative observation and interviews have been used to develop an operational model to describe agent information behaviour as indicated in Figure 3. Three themes were identified and discussed by call centre managers and researchers to represent the agent information behaviour in the call centre, and were used to design the behaviour intervention for organizational performance improvements. The themes were maintaining domain information, identifying customer problem information, and seeking problem-solving information. The results of thematic analysis are provided below.

Maintaining domain information

Unlike processing more structured service calls in telephone or credit card call centre, the agents in this study faced complex and complicated situations in that customer problems depended on various reasons, such as customer computer literacy, business knowledge, and relationship with the wholesalers. Domain information for understanding customer problem descriptions and selecting proper answers can be acquired partially through organizational formal training courses. In this call centre, a new agent normally requires three months training before they can confidently process incoming calls. One second line agent noted:

A new agent first undergoes basic service manner training to familiarize with the language and procedures used to process an incoming call. The agent then attends a software orientation course to learn the business rules and operational skills required for the rented software. The agent must also gain knowledge of the computer and telephony integration system. Exams are administered during and after each training course to assess the level of agent knowledge and skills. Following the above basic training, the agent will be arranged to sit alongside an active first line agent to experience the dynamics of incoming call processing from first hand observation. A second line agent becomes 'mentor' for a new agent for whom they provide either professional or social assistance.

Identifying customer problem information

How to assist first line agents to quickly identify problems from customer descriptions has been discussed and recognized as a core issue for reducing the time required for call processing. Although customers may have various styles for describing their problems, there are clues that could be summarized from the historical development of call processing service encounters, since incoming calls are recorded in the computer and telephony integration system. This means that customer descriptions can be reviewed and discussed for discovering possible clues to represent the problems described. The linkages between keywords and the potential problems described was designated as a method in this study for assisting first line agents to capture customer problem information. One second line agent depicted the difficulties faced by first line agents:

For different sets of rented software, generally the same categories of question types are used to classify supplier problems. Twelve question types exist, and each incorporates a set of items for detailed problem descriptions. The question types remain the same for each set of software, while the items in each question type can differ and the items can be adjusted for different service situations by second line agents. First line agents must classify one question type and select one item for each incoming call. Given a total of 424 items, first line agents frequently select wrong items. The classification of correct question and item types has been assigned as a performance indicator for first line agents.

Seeking problem-solving information

Problem-solving information cannot be easily provided in formal training courses; even experienced agents have difficulties describing their problem-solving processes in detail. Although the computer and telephony integration system does provide some problem-solving guidelines, there are subtle differences in each problem that would require different problem-solving information for each customer. During an interview, one manager expressed that such information is valuable organizational asset that should not be limited to individual agents. For accumulating problem-solving information, one first line agent said:

I take notes in situations involving new operational information and skills. Mentors are very helpful for resolving difficulties in and after problem encountered. It is difficult to describe customer problems in advance, and most of the problems were not clearly mentioned in the training courses. I do no think that I even clearly understood the problems mentioned at that time. The lunch hour function is also a good gathering that creates a sense of community and enables us to share operational experiences and learn from each others. The computer system contains a set of question and answer pairs that can be consulted when interacting with suppliers. However, searching information from the computer system during a rush service encounter seems infeasible.

Other than personal perspectives on handling information problems, the computer and telephony integration system has become a crucial component for understanding and analysing agent information behaviour in this call centre. We observed two main functions of the system that can have substantial influence on agent information behaviour. One function is a set of call processing interfaces that provide first line agents with guidance on identifying problem information, such as classifying question types for each incoming call and inputting supplier problems. The other function is a set of managerial interfaces that offer second line agents with the opportunities to build up organizational knowledge, such as designing question types for each set of rented software and editing the question and answer knowledge base.

Data analysis of the behaviour intervention

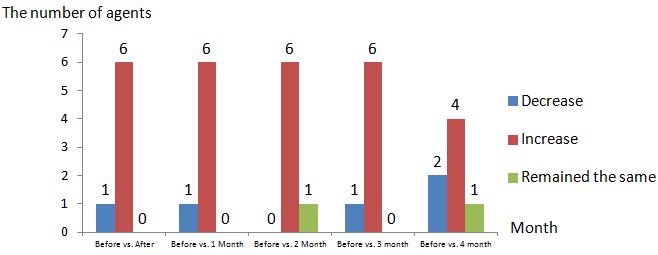

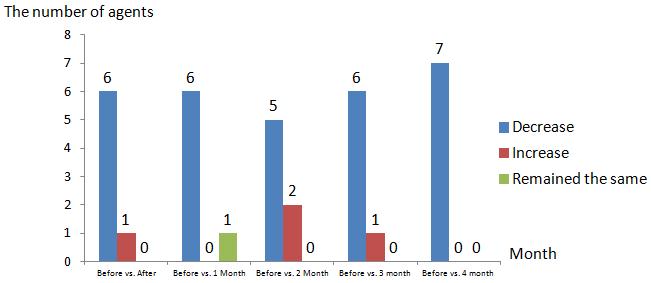

The results from data analysis revealed significant differences between the before and after intervention stages regarding two performance indicators, with averages and standard deviations for the classified ratio of 83.86 ± 2.26, 86.57 ± 3.69, and for required time of 248.28 ± 24.54, 229.42 ± 19.96, respectively. Table 2 indicates the statistical results between the baseline and comparison datasets and between the baseline and the first to fourth month's datasets, respectively. Although the intervention generally has a significant effect, the classified ratio indicator does not exhibit a significant effect during the third and fourth months, and the effect of the required time indicator varies among different months. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the effects of intervention towards the number of agents in each comparison.

| Before intervention | After intervention | 1st month follow up | 2nd month follow up | 3rd month follow up | 4th month follow up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classified ratio (%) | 83.86 ± 2.26 | 86.57 ± 3.69 | 86.86 ± 2.47 | 86.43 ± 4.31 | 87.00 ± 5.41 | 86.14 ± 4.18 |

| Wilcoxon Z values & probabilities | Z = -2.047 P <0.041 | Z = -2.120 P <0.034 | Z = -2.214 P <0.027 | Z = -1.706 P <0.088 | Z = -1.577 P <0.115 |

|

| Required time (second) | 248.28 ± 24.54 | 229.42 ± 19.96 | 228.42 ± 26.31 | 235.14 ± 22.50 | 227.00 ± 19.13 | 226.42 ± 18.68 |

| Wilcoxon Z values & probabilities | Z = -2.197 P <0.028 | Z = -2.201 P <0.028 | Z = -1.014 P <0.310; | Z = -1.014 P <0.310 | Z = -2.366 P <0.018 |

|

Discussion

The field observation and interviews in this study advanced researchers' understanding of agent information behaviour in the context of practical service encounters in the call centre. The understanding contributed to the development of an operational model (see Figure 3) for service encounters description based on the principles of information behaviour (Wilson 1999; Bradley et al. 2010). The operational model was firstly drawn in the call centre and served as a common picture for communication between researchers and managers. The model abstracts agent information behaviour during the service encounter and organizational context areas relating to that behaviour including information need, seeking, searching and use, so that business information including domain, problem, and problem-solving information can be discussed and analysed. This two-level description allows service managers to design precise sequences as guidelines for agents to follow in service encounter areas and to support agents with purposive and non-purposive information sharing activities to enhance their problem-solving skills in organizational context.

As observed in this study, skills for seeking and searching proper information within organizational context can be very different to individual agents (Byström and Hansen 2005). Information sources can exist in explicit or implicit forms that an agent may not have the chance to identify proper sources at first instance (Wilson 1999). Different agents would develop their own information seeking strategies, such as taking notes, participating in social functions, and asking other agents. This implies that implicit learning activities do exist in the context of service encounters, and supporting such activities can generally improve agent information behaviour. Moreover, information behaviour is an evolutionary development (Spink 2010), meaning that agents are required to maintain and update their domain information through continuously seeking and searching for problem and problem-solving information. The cyclic design seen in the descriptive model of Figure 3 enables agents to have many chances for identifying required information sources and allows managers to adjust their efforts in supporting agents toward organizational performance improvements.

The behaviour intervention obtained statistical significance for both classified ratio and required time performance indicator as indicated in Figure 4 and 5. The significant result of this intervention may be partly due to the quick identification of customer problems information with the keyword method during service encounters and sharing problem-solving information within organizational contexts. The keyword method was used in the hope of allowing agents to make sense of problem information and to link internal instinctive information behaviour with external customer problem descriptions. The significant results were also contributed to by the managerial supervision of routine service quality improvements and social networking from colleague relationship developments. In this study we cannot distinguish which of these three factors contributed the most. Since this study did not have a control group, when generalizing the findings the cultural and historical developments of different organizations should also be taken into account to evaluate the effects of behaviour interventions. The varying results obtained from the four-month data sets after the intervention deserved in-depth analysis according to individual agent information behaviour and required further managerial actions.

To ensure reliability of the findings from this practical phenomenon was challenge. This study took a triangulation approach to construct and record the reality of the phenomenon and to enhance the reliability of the findings. The research questions focused on a group of first line agents for their information behaviour in the context of call processing service encounters. At the theoretical level, theories of information behaviour have been used for building the framework of this study, service encounter descriptions from marketing have been used for interactions between agents and customers, and entity-relationship methods from information system have been used for constructing the call centre operational architecture. At the investigator level, researchers were organized as a team for each observation and interview. One manager and two second line agents participated in research activities to assist researchers on collecting data, designing intervention and providing information from both organizational and operational perspectives. At the data collection level, both qualitative and quantitative methods were adopted with a proposed behaviour intervention to advance our understandings on the phenomenon. Although using triangulation method suffered some criticisms (Blaikie1999), the use of more than one approach to investigate a research question can enhance reliability of the findings.

The quantitative methods used in this study aimed to evaluate whether a performance indicator can lead to significant changes under certain statistical tests. However, the insights regarding changes of agent information behaviour can only be obtained through long-term qualitative observation and interview. This study synthesized both methods to the investigation of the research questions that can be understood and accepted by practitioners (Byström and Järvelin 1995; Byström and Hansen 2005; Clarke and Nilsson 2008). The lengthy research phase in this study provides a detail step that can be used as a framework for describing and modelling information behaviour in service encounters and for designing managerial interventions regarding organizational performance improvements. Additionally, service businesses are operating in a dynamic and changing environment and so long-term relationships between researchers and practitioners (Nardi 1996; Wilson 2005) are crucial for researchers to obtain real world information and for practitioners to benefit from the results achieved by both parties.

Conclusion

Information behaviour has become an important aspect in the studies of knowledge-intensive and people-centred service businesses. This study applied understandings from information behaviour studies to model information behaviour in real world service encounters and to discover opportunities for organizational performance improvements. The research processes involved and results obtained in this study have been used to adjust certain operational procedures used for supporting agent information behaviour in the call centre. Service organizations are paying more attentions on the management of agent information behaviour and approaching to academics for theoretical model building. The proposed information behaviour research approach has advanced our understanding of information behaviour in the organizational context and can be used as a framework to analyse complex information behaviour in practical service encounters. This understanding can help researchers in building a theoretical framework to analyse and explain such behaviour and help practitioners on improving their explicit performance indicators and establishing implicit business culture. Further research is required to explore whether the approach used in and results obtained by the present study are applicable to understand other practical service encounters.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the National Science Council, Taiwan, under grant NSC95-2745-H-182-005-HPU. The authors would like to express sincerely appreciations to the anonymous reviewers for their enormous patient and detailed instructions on the efforts to improve the quality of this manuscript.

About the authors

Yung-Hsiu Lin received his Ph.D. degree in Graduate Institute of Business and Management from Chang Gung University, Taiwan, in 2011. He is a lecturer in Department of Information Management, Ta Hwa Institute of Technology, Taiwan. His current research focuses on service description and modeling of healthcare applications. He can be contacted at: lin021060@gmail.com

Rong-Rong Chen received her Ph.D. degree in Graduate Institute of Business and Management from Chang Gung University, Taiwan, in 2011. She is an Engineer in Service Systems Technology Center, Industrial Technology Research Institute, Taiwan. Her areas of researches are: quality metrics management, technology acceptance model, healthcare information management, and data mining. Her contact is: RongRong@itri.org.tw

Her-Kun Chang is a Professor in Information Management at Chang Gung University, Taiwan. He received his B.S. and Ph.D. degrees in Computer and Information Science from National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan, in 1989 and 1994, respectively. His current research interests include health information management, distributed information processing, data mining, and service management. He can be contacted at: hkchang@mail.cgu.edu.tw