vol. 15 no. 1, March, 2010

vol. 15 no. 1, March, 2010 | ||||

Conceptual innovations in information science are important sources of introducing new theoretical frameworks. In this paper we examine information ecology as part of emerging science 2.0 and reflect on reconsideration of information literacy in information science. Science 2.0 combines technological innovations with knowledge of social systems (Shneiderman 2008). In science 2.0 collaboration-centred, socio-technical systems dominate. As examples we can mention Web 2.0, social networking, blogging and citizen journalism and patient-centred medical information systems. Science 2.0 will be oriented to human relationships in social (electronic) networks including trust, empathy, responsibility, privacy. This represents a challenge for information science concentrated on information processing and use.

Information ecology examines the position of human beings in information places and spaces. These complex relationships are manifested by sense-making in the information environment. Information literacy can be considered as part of these relationships at two levels. The first level includes relationships between individuals and information systems in information seeking and uses (Web services, tools and products). The second level is represented by interactions in social networks and social media.

This paper attempts to review if and how information ecology contributes to the information literacy concept. It is not aimed at analysis of guidelines and standards, but draws on our earlier research based on empirical data on information use. We suppose that ecological dimensions of information literacy are closely tied to knowledge of information behaviour styles and relevance assessment. The first section determines background, research questions and methodology. Next sections review several concepts of information ecology and selected models of information literacy. Information styles and information horizons are described and recommendations for students' information literacy presented. Results of two research projects on users' behaviour and relevance assessment are synthesized. In conclusion a model of ecological dimensions of information literacy is presented.

Potential benefits of the information ecology perspective for information literacy can be seen in an holistic view of activities of people in the information environment. The emphasis is put not on information skills, but on interconnections of people and information and on ways of integrating information use into the natural human information environment. Most important ecological dimensions of information use include adaptations, monitoring of the information environment, filtering of information and social co-operation.

In this paper we consider the following questions: How should we reconsider information literacy in the context of information ecology? Can we prove the shift in interpretations of information literacy from text-oriented towards socio-cultural perspective by examination of its ecological dimensions? Is information ecology a productive framework for the improvement of information literacy practice (teaching and learning)? How can we apply results of previous empirical research on information styles and relevance assessment to development of students' information literacy?

Earlier empirical data based on quantitative and qualitative methods (mainly surveys, interviews and concept mapping) are further analysed and synthesized in characterization of information styles and relevance assessment. Further interpretations of previous research projects are applied to derive ecological dimensions of information literacy. The term dimension is used here as appropriate for description of holistic perspective on facets or aspects of information literacy.

The focus of information ecology is on human information behaviour and on information use. We suppose that empirical data on users' behaviour can help disclose new aspects of information literacy and build new models. At the empirical level practical recommendations for information use should be introduced. Another assumption is that the perspective of information ecology could help improve the teaching of information literacy and its integration into guided learning at various levels of education. As examples of new ecological tools we present building of students' information horizons and a concept map resulting from research on relevance.

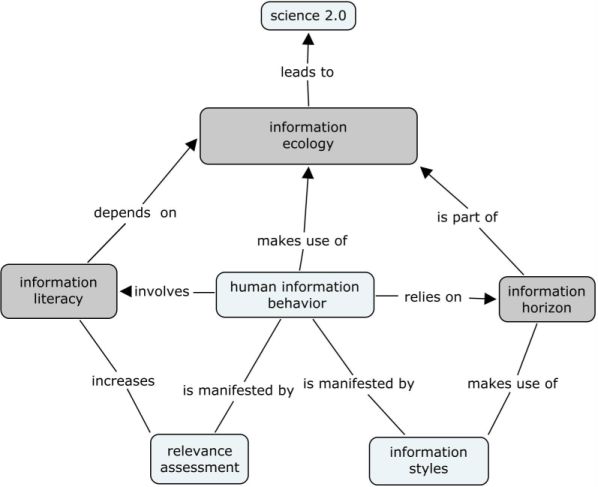

For a theoretical methodological perspective we chose the following: cognitive construction of meanings for information literacy and relevance assessment, sense-making for information behaviour styles and activity theory for modelling ecological dimensions of information literacy. Relationships between main concepts in this paper are depicted on Figure 1. Information ecology comprises interconnections between humans and information environment. It subsumes information behaviour as activities in the information environment Information behaviour relies on information horizon and is manifested by information styles and relevance assessment.

The concept of information ecology emerged from information management and information behaviour studies. It is based on complex relationships between humans and technologies while using information in communities and organizations. Information ecology was determined by Davenport and Prusak (1997) as making information meaningful. Information ecology as a metaphor should help in managing the information environment and information behaviour styles.

Another concept of information ecologies (Nardi and O'Day 1999) is based on relationships between information technologies and people in transforming information to knowledge. Information ecologies represent the procedures, goals, values of communities, which are supported by technologies. Information ecologies are places where people use tools and help each other in information activities through social relationships.

An ecological model of information seeking and use (Williamson 2005) depicts a social actor involved in such settings as information needs, specific personal, physical, working and social contexts. The features of adapting and monitoring of information environment are here emphasized.

Based on environmental psychology, an ecological constructionist model of user information behaviour (Nahl 2007) was developed. It integrates the affective, cognitive and sensorimotor parts of information activities.

Information ecology is also connected with studies of affective information behaviour (Nahl and Bilal 2007). Emotions influence perception and use of information as well as relationships to information technologies. Nahl explained the affective revolution in information science with emphasis on affective filters in information seeking and the evaluation of information. A model of the affective information behaviour ecology (Given 2007) identifies macro- and micro-emotional contexts that shape students' information behaviour. The author calls for more attention to affective dimensions of services and products in the academic information environment.

Our concept of information ecology is based on meaningful information activities in the information environment with regard to information behaviour styles of different social actors. Information literacy and relevance judgments are often intuitively involved in information activities and can be reconsidered in a new context of information ecology.

Information literacy is here regarded as knowledge, skills and efficient information practices in human information behaviour. Educators all over the world developed learning strategies for students with respect to recognition of information need, development of information strategies, use of information sources and building of pathways for gaining knowledge.

Most important standards of information literacy include standards for students' learning for schools (AASL and AECT 1998), the Association of College and Research Libraries information literacy competency standards for higher education (2004) and the Special Libraries Association competencies of information literacy (Abels et al. 2003). Information literacy has also been supported by international organizations (especially UNESCO and IFLA). In library and information science three models dominated in modeling information literacy: Eisenberg and Berkowitz's Big6skills, Doyle's attributes of the information literate person (Doyle 1992) and Bruce's seven faces of information literacy (Bruce 1997).

Information literacy in Eisenberg and Berkowitz's (2009) model of Big6 steps include task definition, creating information seeking strategies, locating and access to information, use of information, synthesis of information and evaluating information. The model was developed in the 1980s. While Doyle specifies attributes of an information literate person (e.g., recognition of information need, formulating questions, accessing sources, evaluating information, organizing information, integrating information), Bruce's model is more ecological in that it sees information literacy as experiencing information use, information practices and reflection. Her seven facets of information literacy experience include: information technologies for retrieval and communication, information sources, information process, information control, knowledge construction, knowledge extension and wisdom (Bruce 2002).

Known patterns of students' information behaviour have revealed common characteristics of students' learning styles in different countries. For example, Limberg (Limberg 2000) determined three styles of information seeking and use in Swedish schools (fact finding, balancing information or forming a personal standpoint, scrutinizing and analysing). She also discovered that students who approached information seeking and use in more sophisticated ways also achieved better learning outcomes. This depended especially on understanding, interpretation and reproduction. Limberg's methodological approach based on phenomenography comprises ecological dimensions when studying complex phenomena of information needs and information literacy in natural environments and ways of experiencing information use (Limberg 2000).

Research in library and information science (e.g. Kuhlthau et al. 2007; Limberg 2007) confirms that information literacy develops from basic competencies (reading, writing, numeracy, basic cognitive information processing) through information and communication technology skills, to cognitive processes of problem-solving, communication and decision making. Another perspective integrates information literacy into a set of other literacies or multiliteracies (social, scientific, economic, civilization, cultural, etc.) Information literacy is regarded as a sociocultural practice (e.g., Lloyd 2007). A situated perspective puts information literacy into various social contexts (work, education, leisure, everyday information practices). From the perspective of metacognition information literacy includes self-appraisal and self-management in information use. Guided inquiry concept (Kuhlthau et al. 2007) then introduces the support of students' own natural ways and styles of information literacy development in learning. In the electronic environment users can form their own information grounds and systems of personal information management.

Common features of information ecology models and information literacy models are interconnections between macro- and micro-environments, human information behaviour and sense-making through cognition, communication, collaboration, evaluation and use of information in information activities. However, little attention has been paid to information styles and relevance assessment as parts of information literacy. That is why we summarize these aspects in next sections based on results of our research at the Department of Library and Information Science, Comenius University Bratislava.

We regard information style as generalizations of typical ways and preferences of people in information processing and use which depend on personality and tasks (Solomon 1997; Heinström 2003). Human information behaviour in the electronic environment is marked by easy access, quick online reading and social networking. Changes in users' information behaviour are influenced by new tools and services of digital libraries. Young students are digitally literate, prefer visual information processing, inductive discovery, fast response time (Oblinger and Oblinger 2005). The Net Generation exhibits tendency to socialize and participate in networks. Although many surveys generalize their patterns of information use, the information strategies of individuals may be unique. From the viewpoint of information literacy the problem is that students behave like digital consumers in digital spaces (Nicholas et al. 2005) and that social networking and consumer Websites change their behaviour in the forms of education, learning and scholarship. Other research (Head & Eisenberg 2009) confirms that students conceptualized information seeking as a fast, pragmatic task and not as an opportunity to learn and construct meaning. Important contexts of information use were identified as big picture, language, situation and information gathering.

When modelling information literacy it is important to recognize the information style and find out an efficient type of its natural support. If we integrate information styles into information literacy, then we can develop ecological information literacy, i.e., the natural development of affective, cognitive and sensorimotor components of information use (Nahl 2001).

An information environment can be determined as information, human, technological and organizational resources aimed at the support of information activities. Our studies into users' information behaviour of academic libraries in the project on the Interaction of Man and Information Environment confirmed two information styles of students' behaviour, i.e., the pragmatic and analytic styles. We ran a series of surveys in academic libraries based on an original methodology which integrated knowledge from social and cognitive sciences into information behaviour. Information seeking preferences and perceptions, use of electronic resources and electronic publishing were analysed. The conception and methodology were reported elsewhere (Steinerová and Šušol 2005; Steinerová et al. 2004).

The pragmatic style prefers simple access to information, simple organization of knowledge, low cost and fast access to electronic resources (quantity and time). The analytic style is marked by deeper intellectual information processing and puts emphasis on reliability and verification of information and reviewing process (quality and relevance). In our surveys we found out that pragmatic style of information processing dominates.

Typical differences between these two styles are summarized in table 1.

| Pragmatic | Analytic | |

|---|---|---|

| seeking | horizontal | explorative |

| terminology | clear, simple | multidisciplinary |

| assessment | surface, serendipity | experience in relevance judgments |

| organization | surface, field dependence | integrative, based on expert knowledge and experience |

| planning | intuitive, simple queries | complex queries |

| purpose | orientation | intellectual processing |

| emotions | trust, optimism | doubts |

| motivation | fast solution | understand contexts |

| Access to information | navigation | interpretation |

For integration of information styles into information literacy development it is important to understand what is important to students and how they learn best and work with information. Within the pragmatic style they would not read extensive texts, they are experiential learners. Critical reading is used especially at higher levels of education and in the social sciences and humanities. The challenge is how to accommodate dominant pragmatic information and learning styles to the needs of building knowledge in the analytic style.

The ecological dimensions of information literacy can be determined by changing, interactive information activities of social actors (e.g., students' learning, citizens' information use, education and research of scientists and educators). From different viewpoint information literacy is embedded in ecological characteristics of information environment determined as mixture of sources, systems and services managed by a social actor.

Two stages of information seeking were determined in our research, i.e. the orientation and the analytic stages. In the orientation stage it can be productive to build an information horizon as part of information literacy development (Savolainen 2008; Sonnenwald et al. 2001). An information horizon is a map of information sources including experts, criteria of source preferences, issues of interest and information pathways. It also uses criteria for relevance assessment, especially credibility and cognitive authority and contexts and situations which make an impact on the added value to information.

By depicting an information horizon we develop information strategies as a special approach to solving an information problem. Information activities then involve orientation (perception of problem, setting the goal, analysis), strategy (choice of procedures, practices) and synthesis and verification (feedback). While building information horizons people often form a hierarchy of information and information sources (most relevant, sources of secondary importance, peripheral). In our memory we have recorded successful strategies and errors which we use as examples of building a new information horizon.

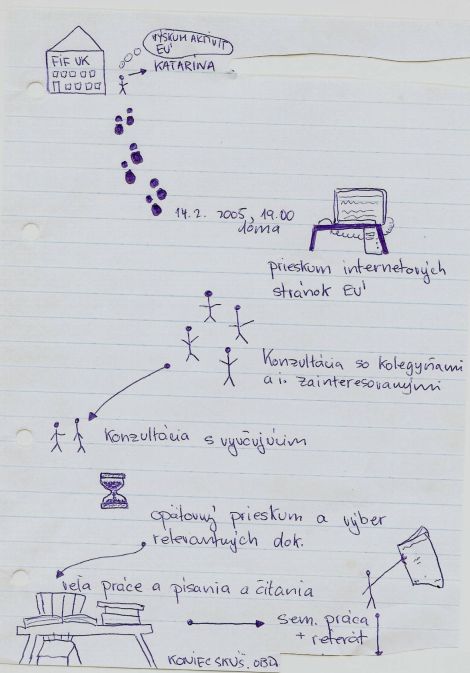

The information horizon concept was used as a case study in the course on Information Retrieval and Seeking. Graphs of our students proved that they relied on their previous experience and could develop their information literacy when they see information sources, order of their use and their representations placed into the information horizon. Examples of information horizons of students of library and information science in Bratislava are shown in Figure 2.

Based on results of our surveys and on case studies of students' information horizons we developed a set of recommendations for students' information literacy:

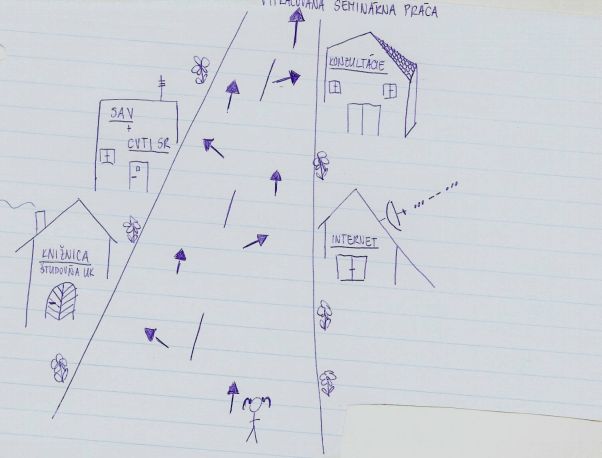

Another key part of ecological approach to information literacy is the concept of relevance. In our second project on Information use and information behaviour we examined relevance judgments of doctoral students (Steinerová et al. 2007). Based on our research we articulated a set of recommendations for relevance assessment as part of information literacy (Steinerová et al. 2010).The study of relevance as part of information use by twenty-one doctoral students was designed within a phenomenographic approach (Steinerová 2008). Semi-structured interviews as a main method of gathering data were applied. Students were selected from social sciences at the Faculty of Philosophy, Comenius University Bratislava, Slovakia. Research questions concentrated on perception of relevance, manifestations of relevance in the electronic environment, ways of categorization and typology of relevant information. Results were visualized in concept maps.

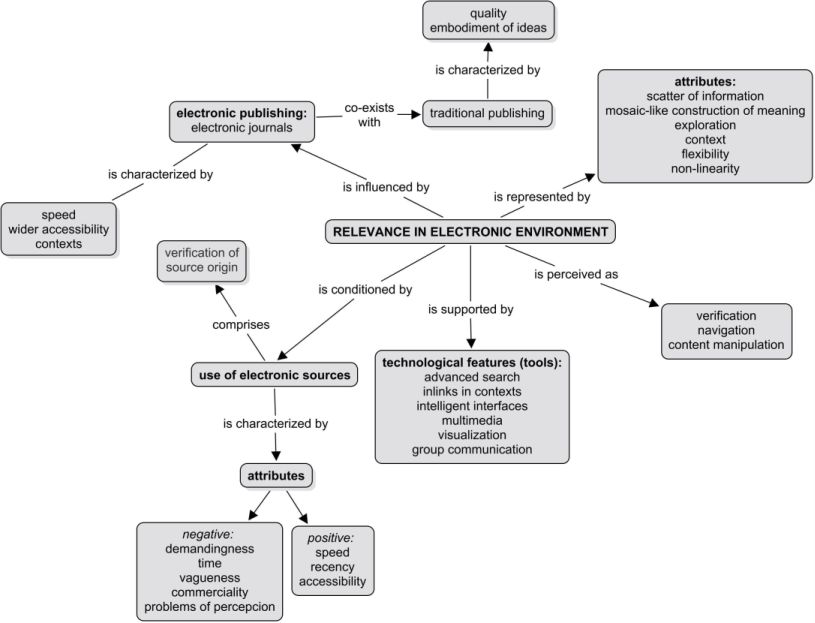

An example of a concept map of relevance in the electronic environment is on the Figure 3.

Respondents confirmed relevance as value, utility and importance. Main findings suggest that the same criteria are used through different contexts and are related to development of information needs. Relevance judgment was confirmed as multidimensional process, based on multi-criteria cognitive processing. Relevance is experienced and integrated by emotions, especially delight, discovery and anger.

From the perspective of information literacy we found out that users need support for discovering, decision-making and participation. Policy makers should consider relevance behaviour in information strategies of education and information literacy.

We suggest that relevance assessment should be deliberately developed as part of information literacy development. Concept maps can support relevance and information literacy development. Concept maps are representations of spatial information and help develop cognitive processing, filtering and adaptations. Students can build their understanding of a topic with the use of such tools as C-maps (Novak and Canas 2008). They can construct both meaning and relevance in the electronic environment. Resulting models of relevance emphasize interaction, linking, visualize concepts and relations, as well as community and collaboration (Steinerová 2008).

Results also determined emerging patterns of relevance in the electronic environment. Hierarchy and associations of knowledge organization support relevance judgments Collaborative use and flexibility help students build their relevance assessment. Relevance in the electronic environment is marked by non-linearity, flexibility of navigation, high-level visualization. Quest for the origin of the source is facilitated by such characteristics of electronic sources as scattered information, serendipity of information discovery, context and non-linearity. Information literacy requires digital skills and additional ethical awareness, as information processing in the electronic environment integrates creation, seeking and use.

Frequent use of electronic sources is conditioned by contexts: topics, disciplines, tasks. In the electronic environment students appreciate topicality, speed and technological features of linking. Printed sources were approached in a more emotional way, putting stress on readability and reliability, quality, intellectual depth, stability, predictability. Several students admitted that manifold mediation in electronic texts make the construction of meanings and relevance assessment more complicated.

Based on our research we articulated a set of recommendations for relevance assessment as part of information literacy. Relevance connects information literacy with critical evaluation of information sources.

Based on previous analyses ecological dimensions of information literacy include the semantic dimension (relevance), the visual dimension (information horizon, concept maps), the behavioural dimension (information style) and the social dimension (community, values).

Ecological dimensions of information literacy are derived from the following assumptions:

Information literacy is interconnected with digital skills and ethical awareness (fair use). The tools for satisficing (completion of information seeking) and optimizing in information systems (Nahl 2007) can help assess relevance and make sense of information. The main ecological features of information literacy are determined as adaptations and filtering. They support transition from information to knowledge.

As examples of tools for support of information literacy we can mention concepts maps, topic maps, intelligent thesauri or complex ontologies. We regard these tools as crucial in information ecology research as cleaning filters that support sense-making. Information literacy development should support natural information activities and user pathways in electronic environments. This support is represented by navigation, filtering and help with cognitive and affective overload.

Information literacy from the ecological perspective draws also on the activity theory (Wilson 2006). The information activity can be modelled by the Engeström's model triangle composed of three components: man, information objects and tools. This can be combined into such activities as production, consumption and distribution of information. Besides communicative tools an important role is played by community, values, division of labor and collaboration. Cognition and communication, adaptation and interaction, relevance, satisficing and optimizing are crucial principles for modelling information literacy.

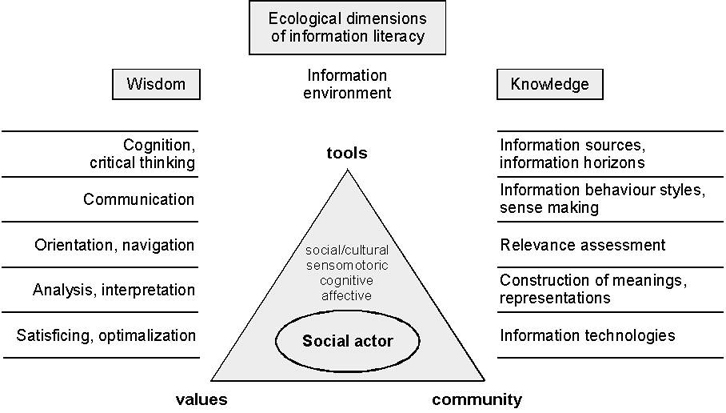

A model of ecological dimensions of information literacy (Figure 4) connects micro-level of information literacy (affective, cognitive, sensomotoric, social strata of social actors) with macro-level of information environment. Social actor builds his information literacy as a pathway through the information environment. On this pathway he uses a set of values (for relevance assessment), special tools (language, knowledge organization tools) and acts as part of communities (operated by group standards, values, social roles and communication patterns). The left side of the model integrates intellectual processes of information management with their transformation to wisdom as knowledgeable decisions. The right side of the model depicts interconnections of information sources and information processes. Links between external and internal environments are manifested by use of information sources, information technologies, information styles, relevance assessment and by construction of meanings. Both sides frame information literacy as transition of information to knowledge. The model generalizes our empirical data on information styles and relevance behaviour. Ecological dimensions of information literacy represent development of information literacy by existence, activities and movements in the information environment.

Thus, information ecology of information literacy can be determined as a way of information existence in the information environment. It is not the volume of information or immediacy of delivery that matter but tools for support of making sense and transformation of information to knowledge.

Ecological dimensions of information literacy can be further elaborated and the following questions can be asked: How to provide contexts for sense making? How to develop information literacy by learning to know and learning to do? Which digital tools can make information use more efficient? and What are the connections between information literacy and learning in communities (learning to live together and learning to be)?

Information ecology helps us identify those factors that make an impact on the information environment and tools for eliminating information overload and risks of information use. Ecological dimensions are determined at micro-level (individual cognitive, affective, sensomotoric skills in building information horizons and pathways) and at macro-level (information sources, systems, environments). In interactions between these levels and factors we can follow continuity and discontinuity of information literacy development. It covers formal and informal communications, collaboration, quality control, information overload, creativity and knowledge production Ethical, legal and security awareness and standards are other ecological dimensions of information literacy which are out of the scope of this paper.

Information ecology concept contributes to information literacy by holistic view on information processing and use. Ecological theories of human information behaviour place human beings in the centre of information environments. Information ecology helps reconsider information literacy in contexts of science 2.0 aimed at integration of technological innovations and social information processes. While in technological concepts people had to adapt to technologies, in ecological concepts technologies are adapted to information needs and become parts of information literacy.

Several models of information ecology and information literacy have been developed so far. These models depict cognitive processes and skills required for information use. From our perspective we integrated information behaviour styles and relevance assessment into ecological dimensions of information literacy which include especially semantic, visual, behavioural and social dimensions. As examples we mentioned students' information horizons and concept maps. We derived recommendations for support of students' information literacy and for relevance assessments. This approach fills the gap in integration of relevance research into information literacy concepts.

Information literacy in the electronic environment develops towards new ways of communicating in short-term groups (e.g., classroom) or longer term groups (family, friends).

Information habits of students in the electronic environment indicate that simplicity, attractiveness, images and immediacy dominate the information use. That is the reason why ecological models of information literacy emphasize navigation, personalization and visualization. Guided inquiry promotes analytical information behaviour style and practical information processing skills. Guidance is provided in development and adaptations of users' information horizons and strategies.

Concept mapping and other visual perception tools support information literacy by pointing to landmarks, connectedness, visual hierarchy, spatial proximity, colors, shapes, etc. The networked social library requires information literacy based on interactive features of collaboration, creativity, production and community building. Ecological dimensions of information literacy can be mirrored in digital libraries in new rules of information processing and use. The presented model of ecological dimensions of information literacy interconnects tools, values and communities that shape information activities. This can be applied to practical information literacy development of students integrated in electronic environments.

Benefits of ecological dimensions of information literacy are in mastering relations between external and internal information environments. The model could support design of digital libraries using resource-based learning, problem-oriented and project-oriented learning, multimedia learning, e-learning, etc. Understanding ecological dimensions of information literacy and more empirical data can be beneficial for development of information literacy strategies at various levels and situations of education and learning.

This paper was developed as part of the research project VEGA 1/0429/10, supported by the Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic.

Jela Steinerová is Professor in the Department of Library and information Science, Comenius University Bratislava, Faculty of Arts, Bratislava, Slovakia (professor, Comenius University Bratislava, 2010). She can be contacted at jela.steinerova@fphil.uniba.sk

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

© the author 2010. Last updated: 15 December, 2010 |