Architectures, algorithms and agency: the information practices of YouTube content creators

Michael Olsson

Introduction. This paper reports the findings of a study of the information practices of YouTube content creators. It uses the concept of practice architectures developed by Kemmis and his collaborators to explore the relationship between participants’ information practices and the practice architectures (cultural-discursive, material-economic, social-political) they occur in.

Method. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken via Zoom with 13 YouTube content creators. Two further participants who were unable to take part in interviews provided written responses to the interview guide questions.

Analysis. Analysis was undertaken using an inductive, thematic approach informed by the conceptual framework. Participants’ feedback on emerging themes was sought and incorporated into the findings.

Results. The study reports findings in relation to participants’ skills development (technical, writing, performance); research and the issue of paywalls restricting access to academic research; understanding their audience via YouTube analytics and viewer comments; the unintended negative consequences of performance analytics; and participants’ lack of agency in relation to the YouTube algorithms that control who views their videos and how they are rewarded.

Conclusions. Participants’ information practices are always shaped by the cultural-discursive, material-economic and social-political operating in the practice architectures they work within.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2242

Introduction

This paper reports the findings of a study of the information practices of YouTube content creators. Alternative media platforms such as YouTube have become significant actors in the global information environment in recent years, a trend which the ongoing pandemic has only accelerated. Adopting an information practices approach affords the opportunity for the researcher to consider YouTube content creators not as isolated individuals but as social actors whose practices are inextricably linked to their social, technological and discursive environment/s.

In this current study, the concept of information practices has been informed by the work of a range of authors including (McKenzie, 2003; Savolainen, 2008; Talja, 1997, 2018) and, most notably, (Lloyd, 2009; 2010; 2011; Lloyd and Olsson, 2019; Olsson and Lloyd, 2017). The study adopts Lloyd’s definition of information practices as:

An array of information-related activities and skills, constituted, justified and organised through the arrangements of a social site, and mediated socially and materially with the aim of producing shared understanding and mutual agreement about ways of knowing and recognizing how performance is enacted, enabled and constrained in collective situated action. (Lloyd, 2011, p. 285)

In addition to information practices approaches within information studies, the study has also been informed by a range of theories from outside the discipline, including Sense-Making (Dervin, et al., 2003) multimodal discourse analysis (van Leeuwen, 1999) and practice theory (Gherardi, 2008; Nicolini, 2012; Kemmis, et al., 2014).

In exploring participants’ information practices, the study also makes a contribution to the emergent field of information creation research. Huvila, et al. (2020) have pointed out that information studies researchers have focused much less attention on practices relating to how information is created than on other aspects of information behaviour and practices, such as information seeking. The study can be seen as one researcher’s attempt to develop a more holistic approach which acknowledges the interrelated and ongoing nature of information practices.

The study aims to gain an understanding of the relationship between YouTube content creators’ information practices and their socio-technical environment. It therefore uses practice architectures (Kemmis, et al., 2014; Mahon, et al., 2017) as a conceptual lens through which to structure its investigation of the cultural-discursive, material-economic and social-political arrangements which both afford and constrain participants’ information practices.

Conceptual Framework

Whilst practice theory has been used to study YouTube content creation in other disciplines (e.g. Grant and Dacin, 2019; Pires, et al., 2019), its most notable use in an information studies context has been Thomson (2018) in her important doctoral work Doing YouTube: information creating in the context of serious beauty and lifestyle YouTube. This study examined ‘how serious (i.e., consistently uploading) YouTube content creators generate and disseminate beauty- and lifestyle-related information with their videos’ (Savolainen and Thomson, 2021, p. 7). Based on this study, Thomson created a model of information creating outlining the ‘episodic, sporadic, and ongoing information activities in serious beauty and lifestyle YouTube information creating’ (Thomson, 2018, p. 257). More recently, Thomson has collaborated with Savolainen, incorporating her work on information creating into an expanded version of his existing ‘model for everyday information practices’ (Savolainen and Thomson, 2021).

While the two studies necessarily cover significant common ground and have many similar findings, their focus and conceptual framework are somewhat different. Thomson, drawing on Sonnenwald and Iiovonen (1999) and Hartel’s (2010) adopts an episodic focus, taking as her unit of analysis ‘a short-duration episode -a real-time task that consists of steps leading to a distinct outcome’ (Savolainen and Thomson, 2021, p. 7). In this, Thomson’s study can be seen to be aligned with an important focus within practice theory: ‘To know is to be capable of participating with the requisite knowledge competence …On this definition, it follows that knowing in practice is always a practical accomplishment’ (Gherardi, 2008, p. 517).

The present study adopts a different approach: one which adopts a broader focus seeking to understand not only how participants complete tasks but also to gain some insight into how their sayings, doing, and relatings (Schatzki, 2002; Kemmis, et al., 2014) are related to the complex practice architectures with which they interact. The actors in this environment include not only other people but a range of socio-technical systems that both enable and constrain their ability to pursue their practices as content creators. For the present study, the work of Kemmis and his collaborators is particularly important. Building on Schatzki’s work, their aim has been to provide insight into how practices shape and are shaped by the material arrangements existing in a given site.

In endeavouring to relate participants information practices to their social worlds, physical and virtual, the study has also been informed by the concept of practice architectures as developed by Kemmis and his collaborators, including information practices researcher Annemaree Lloyd (Kemmis, et al., 2014; Mahon, et al., 2017; Lloyd, 2010). Practice architectures has emerged

…through a process of problematising practice theory and offers a distinctive ontological view of what practice is, how practices are shaped and mediated, and how practices relate to each other … the theory makes a unique contribution to the practice theory debate through the ways that it politicises practice, humanises practice, theorises relationships between practices, [and] is ontologically oriented (Mahon, et al., 2017, p. 2)

Practice architectures is a particularly useful conceptual tool for the present study because it is designed to provide ‘an account of what practices are composed of and how practices shape and are shaped by the arrangements with which they are enmeshed in a site of practice’ (Mahon, et al., 2017, p. 7).

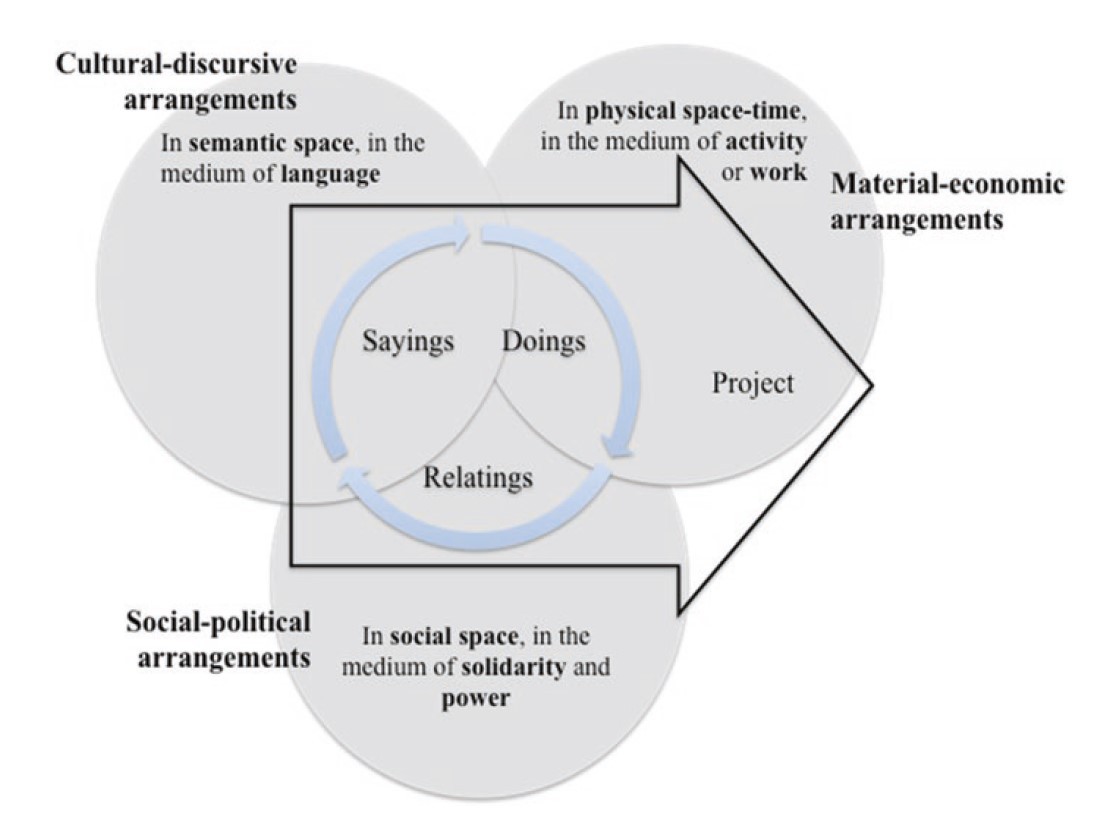

Figure 1: The media and spaces in which sayings, doings, and relatings exist. From Kemmis, et al. (2014, p. 34)

The study uses Kemmis, et al.’s (2014) model (Figure 1) as a conceptual lens through which to explore the ways in which participants’ information practices do not occur in isolation but are inextricably linked to the practice architectures that make up their information environment/s. These architectures are multifaceted and include different types of arrangements:

cultural-discursive: ‘the resources … that prefigure and make possible particular sayings in a practice, for example, languages and discourses used in and about a practice’ (Kemmis, et al., 2014, p. 32)

material-economic: ‘are resources (e.g., aspects of the physical environment, financial resources and funding arrangements, human and non-human entities, schedules, division of labour arrangements), that make possible, or shape the doings of a practice by affecting what, when, how, and by whom something can be done’ (Mahon, et al., 2017, p. 10)

social-political: ‘are the arrangements or resources (e.g., organisational rules; social solidarities; hierarchies; community, familial and organisational relationships) that shape how people relate in a practice to other people and to non-human objects; they enable and constrain the relatings of a practice’ (Mahon, et al., 2017, p. 10)

These arrangements should not be seen as discrete domains but are ‘bundled together in characteristic ways in practice landscapes’ (Mahon, et al., 2017a, p. 13). Although the practice architecture approach has been used as a lens to explore YouTube practices by education researchers (e.g. Araos, et al., 2021; Kaukko, et al., 2021), these studies have largely focussed on platform users rather than creators in formal education settings.

Information seeking research has been critiqued (Talja, 1997; Talja and Hansen, 2005; Olsson, 2005; Hansen and Widen, 2017) for its narrow construction of context in focusing on the individual information seeker. On the other hand, the macro-sociological, historical focus of philosophers and theorists such as Foucault (1972) may seem difficult for many information researchers to apply to the contexts and communities they study. The present study might therefore be seen as one researcher’s attempt to find a middle path towards understanding the relationship between people’s information practices and their environment.

Methodology

15 participants took part in the study (6 female, 9 male). All participants ran YouTube channels successful enough that they were monetised. The most experienced participant began their channel in 2007, with the least experienced beginning in 2020. All but one participants’ channels had view numbers in the millions, with the most successful attracting more than 835 million views. All participants’ identities are protected by a pseudonym of their own choosing. Multiple strategies were employed in recruiting participants. An initial sample was chosen from among content creators whose channels the researcher had already followed for a year or more. This was followed up by snowball sampling based on suggestions from participants.

Participants were based in the US, UK, Australia and Egypt (a North American ex-pat). Whilst the sample might justifiably be critiqued for being dominated by the Anglosphere and lacking diversity, the researcher felt that this was a necessary limitation for a preliminary study in a new context, given the researcher’s own background. Rather than potentially impose his own cultural assumptions, the author would prefer to work in future with other researchers from diverse backgrounds to explore the information practices of a more culturally diverse range of YouTube content creators.

In contrast to Thomson’s (2018) focus on a single subject area (serious beauty) the YouTube channels of the participants cover a diverse range of subject areas (see Appendix 1). The study does not seek to make any claims that the participant sample is in any way representative of YouTube content creators as a whole. In so far as a common theme unites their recruitment it is that they all focus on creating content about a specialised area or field for general audiences. This was felt to be appropriate for the present study as it allowed the researcher to explore the commonalities and differences in content creators’ relationship with their practice architectures across subject areas. The other common attribute participants were selected for was that, while some do work with others, either through collaborations or employing others for some technical tasks, all participants were solely responsible for the planning and development of the content of their channel.

Interviews were carried out using Zoom virtual meeting software and lasted between 58 and 156 minutes with an average duration of 114 minutes. Two participants were unable to take part in interviews for logistical or scheduling reasons but volunteered to provide written responses to the interview guide questions.

The design of the interview guide (Appendix 2) incorporated some elements inspired by Dervin's sense making methodology (Dervin, et al., 2003) with its emphasis on the participants as experts in their own life-world (Dervin, 1999). However, the overall approach was also influenced by more conversational approaches to research interviewing (Seidman, 1991). The aim was to afford the participants the opportunity to talk about their practices in ways that made sense to them. Whilst such an approach undoubtedly makes the interview data less consistent and thus more time-consuming to analyse, it allows the participants greater opportunity to make connections and raise issues that the researcher had not thought of. Interviews were subsequently followed up by the researcher with supplementary questions via email. Follow up interviews with three participants were conducted to explore emerging themes in the analysis to see if they resonated with their own experience.

The interviews were both video and audio recorded through Zoom and were transcribed using the Word 365 transcribe feature and then edited for accuracy by the researcher. Both the transcripts and the audio recordings were used during the analysis process.

In order to get a better understanding of the participants’ work, the author watched a minimum of 25 of each participants’ YouTube videos before interviewing them. This was followed by a preliminary thematic/multimodal discourse analysis of a sample of 5-10 videos. This was used to inform the researcher’s interview strategy but may also form the basis of later publications.

Analysis was undertaken using an inductive, thematic approach (Bryman, 2012). The analysis was consciously informed by the range of theoretical perspectives described in the conceptual framework section above. Nonetheless, the study's aim was not to test the validity of these theoretical approaches, but rather to use them as conceptual tools in developing a contextualised, situated understanding of the relationship between participants' information architectural environments (cultural-discursive, material-economic, social-political) and their information practices.

Feedback on emerging themes was sought from participants throughout the analysis process and their insights and critique incorporated into the findings presented here. As themes emerged during the analysis, the author would contact one or more of the participants whose interview quotes inspired the emerging concept. They would be provided both with my working definition of the concept and the relevant quotes from their interview for context. They were invited to provide feedback and encouraged to raise any objections. Participants‘ feedback allowed the researcher to gain a deeper understanding informed by their insider knowledge. This proved particularly insightful in understanding participants‘ complex relationship with the YouTube platform.

Results

The results presented here do not aim to be exhaustive. Instead, they focus on findings which the author regards as directly relating to the themes of the paper. The author’s aim is that further findings exploring different themes and using different conceptual lenses will appear in future publications. The present paper does not, for example, deal with the relationship of participants’ information practices to the genre/s of videos they produce in any depth as this complex topic will be the focus of a future publication based on ongoing analysis.

Skills development

Technical skills and the material-economic

One of the challenges of becoming a successful YouTube content creator is developing the technical skills required to operate in its material-economic practice architecture (Kemmis, et al., 2014).

Four participants described an educational background which gave them relevant skills and experience:

'I was at [North American university], so I was actually in their film and TV production program ... I was a production major ... and I had a minor in screenwriting [but] for animation I'm primarily self taught'. (Fritz Duquesne)

However, as in Thomson’s study, all participants described the development of their technical skills as being largely a matter of learning by doing.

'I would describe myself as being ... above average tech savvy... I kind of learned a lot about computers and programs ... and I got really comfortable with ... learning as I went along'. (Hatshepsut)

In contrast to the researchers’ previous studies (Olsson, 2016; Olsson and Hansson, 2019; Olsson and Lloyd, 2017; Lloyd and Olsson, 2019), participants made strong use of YouTube instructional videos to develop their technical skills:

'There are loads of really useful stuff on YouTube about video-editing, lighting, thumbnails and things ... I’ve really learned a lot from them'. (Holly)

Their different view of YouTube video’s usefulness no doubt relates to the very different cultural-discursive and material-economic arrangements of their different communities’ practice architectures when compared to those of car restorers, martial artists etc. Whilst the earlier studies examined embodied practices removed from online environments, for content creators such videos provided them with content tailored to the platform and associated practice architectures they were themselves working in.

Writing practices: engaging with the cultural-discursive and social-political

All participants talked about the importance of writing skills and with the aim of being able to engage the viewer’s attention and maintain their interest throughout the video. Ten participants described audience-focused writing strategies:

'How do I distil that into hopefully 30 to 60 seconds of back story that can go at the beginning to let people know what the heck‘s going on? And then how do we make sure that it's sufficiently resolved so that people have closure at the end of the video? And then what can be taught from it? You know, are they just learning something interesting? That may be fine. Or are they learning that something that they might have perceived as being a certain way is actually a different way? ... Or is there a a surprise? Is there an entertaining punchline? You know there's a lot of ways that you can have a payoff on a story...' (Brock Yates)

Four participants had formal education in writing and/or communication. However, they all talked about the limited utility of this experience and, like the other participants emphasised the importance of learning by doing:

'I finished a master’s of science and that was in science communication ... I learned more on the job working as a pseudo journalist about like proper research and like ethics in writing and how to you know format content and different things like that ... than I ever did doing a master’s degree or doing research at the masters level'. (Susie Corkin)

This is not surprising given that whilst the cultural-discursive and social-political practices (Kemmis, et al., 2014) of YouTube owe much to those developed in traditional media, they are not the same. They are multi-layered and complex, and differ according to the topics, genres and audiences that each content creator engages with. It therefore follows that participants needed to adapt their writing strategies to their practice architecture environments.

This need may account for the fact that nine participants reported that watching and analysing videos created by other very successful YouTubers was an important learning tool to inform their own practices:

'I watched a ton of YouTube ... trying to put myself into a position where I can observe and learn I picked a couple of case studies: so I picked a history YouTuber, a travel YouTuber, a musician, ... , I watched a couple ... who were doing sewing stuff before me. I went through their entire catalogue from, ..., years back and I would just ... binge watch in chronological order every video that they had ever put out. Sometimes hundreds because you do learn a lot'. (Emmeline Pankhurst)

Developing their technical and writing skills not only increased their success in the cultural-discursive and social-political domains, it also led to tangible material-economic benefits. As their expertise in these areas increased, so did their audience size and levels of engagement. As these are key success indicators for the algorithms that YouTube uses to determine how much content creators are paid by the platform, they can directly lead to financial benefits for the content creator.

Conceptually, this example is a useful reminder that the different categories or practice architecture arrangements are not separate domains but bundled together in characteristic ways in practice landscapes (Mahon, et al., 2017, p. 13).

Embodied Cultural-Discursive Practices: Constructing a Virtual Self

Just as important as technical and writing skills for YouTube success is the ability to present the material in an engaging way. In a very real sense, this required the participants to develop embodied cultural-discursive information practices that allowed them to construct a virtual self: the persona/version of themselves that their audience engaged with.

Participants’ embodied information creation practices were markedly gendered. For example, in discussing their vocal presentation style three female participants talked about training themselves to use their lower register when presenting because they believed it gave them greater authority:

'...the way that I speak now is much different from how I spoke in my videos two years ago, I realised very quickly that people tend to take more seriously the presenters who speak in a lower voice'. (Emmeline Pankhurst)

In doing so, they mirrored van Leeuwen’s (1999) analysis of female newsreaders and presenters, where audiences were shown to regard those with deeper voices as more authoritative.

By contrast, four male participants talked about not wanting to appear too formal in either their speech patterns and/or appearance, for fear of appearing too intimidating or unrelatable to their audience. One participant talked about developing a speaking style appropriate to the kind of amusing stories he tells:

'I developed a lot of cadence ... an intonation from that which I think has probably served me well, yes, I I didn't do much research into comedic timing, but that seems to have developed well'. (Brock Yates)

Three younger female participants, spoke of their uneasiness about the issue of male audience members objectifying and sexualising their appearance. Whilst they were aware that this is something that the platform’s algorithms tacitly incentivise, they were unwilling to compromise their integrity as well as their personal safety:

'I'm also very aware that there are certain things that I could do to vastly improve my audience, but I'm not really willing to compromise my integrity ... such as doing videos in a tank top or like wearing revealing clothing...' (Hatshepsut)

Three participants (all male) made the design choice to never appear on camera and thus the virtual self their audience engages with was a disembodied voice. In explaining their decision, each of them talked about not wanting to distract from their content:

'I never wanted to show my face on camera ... The only reason this is 'cause I watched lots of art documentaries and I spend my whole time saying get away from the ******* camera! Show me the picture I want to see the picture!' (Gustav Klimt)

Earlier studies of 20th century mass media (van Leeuwen, 1999) would however suggest that the success of this strategy needs to be seen in the context of cultural-discursive practices older than YouTube i.e. that documentaries, newsreels etc. have led the disembodied authoritative (usually male) narrator trope to be recognisable to contemporary audiences.

Material-economic barriers: paywalls and workarounds

All participants demonstrated a high level of expertise in finding the information they needed to inform their content creation. In this, they were aided by previous education and professional backgrounds, with nine holding or working on related university degrees, four of them doctorates, and ten having worked in related industries. All had a passion for their subject area, often going back years before they became content creators. This gave all of them a good understanding of what constituted an authoritative information source in their context:

'I'm a scholar, so I know what a peer reviewed journal looks like. I know what a reputable scholar looks like, so I I would say I almost exclusively use peer reviewed research even when I find that article on Google Scholar'. (Erasmus)

Whilst content creators’ research into the topics for their videos would seem to lie largely in the realm of cultural-discursive affordances, participants’ accounts make clear that one of the major barriers they faced was a material-economic one: access to most academic research is accessible only behind a paywall. Only three participants had an institutional affiliation that afforded them access to relevant full-text databases. The importance of this varied according to the cultural-discursive context of the content creators’ channel. All the study’s participants had a high level of knowledge in relation to their channel’s subject areas, with two participants whose channels were in the leisure domain not raising this as an issue.

Five participants talked about occasionally paying for access to particularly relevant articles:

'In regards to access[ing] stuff behind paywalls, at times I have splashed the cash but on other occasions I have just had to try and find the information elsewhere'. (Gabriel Legg)

Participants’ accounts described a range of workarounds to gain access to scholarly information sources. Most frequently mentioned was the use of online sites that provide open access, such as Google Scholar or JSTOR. Wikipedia tended to be a useful resource and frequent first port of call for most participants.

Four participants described reaching out via their online and personal networks to gain access:

'...the other thing that I've done on occasion is I'm in a number of different Slack channels and Discord channels with other mostly media people. But I'll just ask if anyone has access to that article and get someone to send it to me'. (Susie Corkin)

Material-economic affordances: understanding audiences

Building a career as a YouTube content creator relies on developing a good understanding of one’s audience/s. Participants described a number of resources and strategies they employed to help them develop this.

One of the sources of information provided by YouTube to its content creators is a dashboard of analytics which provides data on audience demographics, view times etc.:

'So there are lots of different things that it tells you: the things which I actually concentrate on are my clickthrough rate, which is how many...went, 'Oh yes, I'll give that a go', and then how many of them subsequently stuck around and watched most of the video...it gives you a little bar chart on Mondays...They give you demographic information, the male to female ratio, the general age range and they also tell you where they're from'. (Holly)

Whilst participants generally agreed that this data was useful in providing them with a broad overview – although three participants described it as not useful at all – most agreed that it was not presented in a way that was easy to understand or apply, nor did it necessarily provide the kind of rich picture they wanted to inform their creation practices.

In order to gain a more nuanced understanding of how audiences view their videos, nine participants talk about reading user comments on their videos, another feature the YouTube architecture provides. Participants talked about the need to balance and weigh the relative merits of the forms of audience information YouTube provides:

'I read comments, which I guess are the main source of information for me. ... But it's sort of a combination [with analytics] because comments are a subsection of a subsection of a subsection of people, and so if one person has said it, you can be pretty sure that several hundred people are thinking it. But on the other hand, you might get a comment which says you should have focused more on ... this section of the video ... but if you look on the retention graph, that's actually when people started bailing out 'cause it was too long and they didn't like it'. (Holly)

Participants therefore described the need to weigh the value of the data the analytics provided and the feedback from comments against their own experience.

In terms of reading comments, one information practice described by five participants was the 24-hour rule:

'I try not to read the comments. So past the 1st 24 hours I don't really read the comments like the people watching in the 1st 24 hours are like [channel] fans. Many of them have degrees in religious studies. They're extremely smart. (Erasmus)

Two participants described this as common among their content creator friends. The idea behind this practice is twofold: firstly, that the most useful comments will be posted in the first 24 hours because that is when the most engaged members of their audience are active; secondly, it is self-protective, in that the number of trolling, abusive and misogynist comments will build up over time, as more casual viewers are brought to their content through YouTube’s Recommend and Autoplay functions. The prevalence of such negative comments and their potential impact on their mental and emotional well-being, was the reason given by four participants for no longer reading comments at all.

Four participants described other social media platforms, such as TikTok and Instagram, as well as the Patreon funding platform as other means they used to engage with audience members.

Going viral: unintended consequences

As an outsider one might reasonably assume that ‘going viral’, having a video 'blow up on the Internet’ as one participant put it would be a 'shining star moment' for any content creator. Yet three participants described how this success, after initial euphoria, led to feelings of intense anxiety in its aftermath:

'What people don't think, and until they actually do go viral is that it is the worst, most anxiety inducing like mental breakdown period of your life. Because all of a sudden you've got thousands or hundreds of thousands of people finding your content ... waiting for you to do something equally spectacular ... you now have this whole new audience base that you have no idea what they're there for. You don't know who they are, what they want, if they're gonna leave tomorrow'. (Emmeline Pankhurst)

Of particular interest in light of the study’s focus on practice architectures was how they described the negative impact of one of the platforms’s technological agents: the analytics providing comparative analysis of the relative performance of their videos. As one participant put it:

'After you’ve gone viral, for months afterwards whenever you look at the analytics, it gives you a graph and a whole lot of figures outlining just how unsuccessful the rest of your content is! ...the longer this goes on, the more convinced you are that it was a fluke and you’re a failure'. (Francis Bacon)

This provides a useful example of how information systems created with pragmatic intentions can have very different consequences depending on the context of the person viewing it. No doubt the designers of YouTube’s analytics dashboard viewed it as a tool to allow creators to track their channel’s progress and incentivise them to produce more watchable content, while at the same time increasing the platform’s profitability for its parent company. What they appear to have failed to appreciate was the possibility that this could lead to anxiety among content creators already conscious that the success of their videos was largely controlled by YouTube algorithms that gatekeep who views their content.

The algorithm and (lack of) agency

Participants’ accounts of YouTube-related information practices demonstrated that they were all experts in navigating the cultural-discursive, material-economic and social-political arrangements of their practice architectures. Despite this success, however, a common theme in participants’ accounts was their frustrations with the barriers raised by a key actor in their material-economic environment: the YouTube algorithms which determine who views their content and how much (or if) they get paid.

Not only did participants view YouTube’s algorithms as opaque, but they also resented the fact that YouTube did not consult or even advise them of changes. Participants’ accounts made their disaffection with their lack of agency clear:

'For me it's it's just distrust. Like it's this amazing tool that's allowed me to reach a big audience. But I'm aware that they could just pull the plug. They could demonetise me like so. The lack of agency is scary. It makes me feel precarious and in the ways that like an adjunct professor might feel like'. (Erasmus)

As another participant put it:

'With the algorithm, it's like working for a boss who changes their mind every day and they will decide whether they pay you or not based on what they feel on the day, it's very unpredictable'. (Hannah Glasse)

Participants’ felt their lack of agency not only because the operation of YouTube’s monetisation rules are not transparent but also are subject to change without consultation or even notice, causing the knowledge they have acquired through experience to no longer be helpful:

'Sure, so you'll hear YouTubers describe the algorithm as a kind of a Wizard of Oz like puppeteer behind the scenes mentality and it changes. And what I mean by the algorithm is that YouTube builds in recommendation engines that are designed to amplify viewer trends based on how much it benefits their aim being serving ads to as many people as possible ... However, the priorities of that algorithm change every six weeks, like clockwork, so they may prioritise, like ratios. They may prioritise, comment, engagement. They may priorities view time. They may prioritise high add rate contents. They may prioritise a lot of different things ... and I'll never know exactly what that is, but I will start to notice that certain content performs better or worse... We don't know how it's going to perform in different algorithms, because of just different trigger points of success'. (Brock Yates)

Participants also raised concerns about how YouTube has changed as a platform as its algorithms are increasingly controlled by artificial intelligence rather than human agents. More experienced content creators talked about no longer having a person at YouTube who liaised with them as they had in the past. One participant talked extensively about her concerns about how changes in the algorithm have affected the content that is promoted, leading to the decline in the quality of content.

'...then with a lot of the algorithm changes, we've found that previously it used to promote creativity. So if you did something new and creative that would get a lot of views, whereas now it promotes copying, so if something is going fairly well and then you'll see 50 other people copy that exact idea because the algorithm‘s ... more likely to promote something they know is going well. So yeah, I found that frustrating 'cause it went from promoting creativity and originality to promoting copying'. (Hannah Glasse)

This participant felt so strongly about this that they have shifted the focus of their content creation to include videos critiquing content factories (commercial organisations often based in the developing world with multiple channels producing 50 or more videos a month across multiple channels with content largely copied from already successful content creators) and their unoriginal, poor quality and sometimes downright dangerous content. They appreciated the irony that these are now the most viewed videos on their channel.

Conclusions

The study’s findings demonstrate that the study’s participants are experts in their life-world (Dervin, 1999) who have developed the knowledge, skills and understanding of the YouTube information environment that allow them to build careers creating content that both entertains and informs viewers around the world. The findings also make clear, however, that understanding their expertise provides only a partial portrait of their information practices.

The study’s findings demonstrate that participants’ information practices are always shaped by the cultural-discursive, material-economic and social-political arrangements operating in the practice architectures they work within. These architectures also include non-human actors that exercise considerable authority around what content creators can access, create and how they are financially compensated for their labour. This can lead to content creators feeling they lack agency, leading to frustration and stress. They also provide examples, such as the performance analytics provided by YouTube, of the ways in which non-human actors can have unintended negative impacts on the people who engage with them.

Nor is YouTube platform the only material-economic system whose architecture constrains the participants’ information practices. Whilst participants demonstrated high levels of information literacy (Lloyd, 2010) in terms of their ability to search for and identify quality research relating to their topics, the fact that much of this information is restricted behind corporate paywalls was a significant barrier reported by many participants. The study’s findings provide an example of how the for-profit nature of academic information access has consequences not just for content creators but indirectly for the millions of viewers who regard them as a trusted information source.

It may be that information practises researchers’ tendency to focus on information in the moment of practice has led to not enough attention being paid to exploring how they relate to their broader socio-material environment. The author acknowledges that this criticism could also justifiably be applied to some of his own past research. The practice architectures framework of Kemmis, et al. (2014) is only one conceptual tool that information practice researchers might use to explore this issue. It is the author’s hope that future research will see a range of these employed to extend our understanding of the relationship between people, information and context.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback.

About the author

Michael Olsson is a Professor in the School of Library and Information Studies Diliman. He is an active researcher in the field of information practices research. He has appeared in international research journals and conferences in a range of different fields, including information studies, communication, leisure studies and knowledge management. He can be contacted at michael@slis.upd.edu.ph

References

- Araos, A., Damşa, C., & Gašević, D. (2021). Exploring affordances provided by online non-curricular resources to uundergraduate students learning software development. In E. de Vries, Y. Hod, & J. Ahn, (Eds.), Proceedings of the 15th International Conference of the Learning Sciences - ICLS 2021, Bochum, Germany, June 08-11, 2021. (pp. 1063-1064).

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Dervin, B. (1999). On studying information seeking and use methodologically: the implications of connecting metatheory to method. Information Processing and Management, 5(6), 727-750. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(99)00023-0

- Dervin, B., Foreman-Wernet, L., & Lauterbach, E. (2003). Sense-Making methodology reader: selected writings of Brenda Dervin. Hampton Press.

- Foucault, M. (1972). The Archaeology of Knowledge. Tavistock.

- Gherardi, S. (2008). Situated knowledge and situated action: what do practice-based studies promise? In D. Barry, & H. Hansen (Eds.), The Sage handbook of new approaches in management and organization (pp. 516-527). Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849200394.n89

- Grant, A., & Dacin, P. A. (2019). "Understanding co-creation through a playbour lens". NA - Advances in Consumer Research, 47, 297-303.

- Hansen, P., & Widen, G. (2017). The embeddedness of collaborative information seeking in information culture. Journal of Information Science, 43(4), 554–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551516651544

- Hartel, J. (2010). Time as a framework for information science: insights from the hobby of gourmet cooking. Information Research, 15(4). http://informationr.net/ir/15-4/colis715.html (Internet Archive)

- Huvila, I., Douglas, J., Gorichanaz, T., Koh, K., & Suorsa, A. (2020). Conceptualising and studying information creation: from production and processes to makers and making. Proceedings of the 2020 ASIS&T Annual Meeting. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.226

- Kaukko, M., Kemmis, S., Heikkinen, H. L. T, Kiilakoski, T., & Haswell, N. (2021). Learning to survive amidst nested crises: can the coronavirus pandemic help us change educational practices to prepare for the impending eco-crisis? Environmental Education Research, 27(11), 1559-1573. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.1962809

- Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P., & Bristol, L. (2014). Changing practices, changing education. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-47-4

- Lloyd, A. (2010). Framing information literacy as information practice: site ontology and practice theory. Journal of Documentation, 66(2), 245-258. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411011023643

- Lloyd, A. (2011). Trapped between a rock and a hard place: what counts as information literacy in the workplace and how is it conceptualized? Library Trends, 60(2), 277-296. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2011.0046

- Lloyd, A & Olsson, M. (2019). Untangling the knot: The information practices of enthusiast car restorers, Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 70(12), 1311-1323. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24284

- Mahon, K., Kemmis, S., Francisco, S., & Lloyd, A. (2017). Introduction: practice theory and the theory of practice architectures. In K. Mahon, S. Francisco, & S. Kemmis (Eds.), Exploring education and professional practice – Through the lens of practice architectures (pp. 1-30). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2219-7_1

- McKenzie, P (2003). A model of Information Practices in Accounts of Everyday Life Information Seeking. Journal of Documentation, 59(1), 19-40. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410310457993

- Nicolini, D. (2012). Practice theory, work, and organization: an introduction. Oxford University press.

- Olsson, M. (2005). Beyond ‘Needy’ Individuals: conceptualizing Information Behavior. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 42(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/meet.1450420161

- Olsson, M. (2016). Making sense of the past: the embodied information practices of field archaeologists. Journal of Information Science, 42(3), 410-419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551515621839

- Olsson, M. & Hansson, J. (2019). Embodiment, information practices and documentation: a study of mid-life martial artists. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Ljubljana, Slovenia, June 16-19, 2019. Information Research, 24(2), paper colis1928. http://InformationR.net/ir/24-4/colis/colis1928.html (Internet Archive)

- Olsson, M. & Lloyd, A. (2017). Being in place: embodied information practices. Information Research, 22(1). http://InformationR.net/ir/22-1/colis/colis1601.html (Internet Archive)

- Pires, F., Masanet, M., & Scolari, C. A. (2019). What are teens doing with YouTube? Practices, uses and metaphors of the most popular audio-visual platform. Information, Communication & Society, 24(9), 1175-1191. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1672766

- Savolainen, R. (2008). Everyday information practices. A social phenomenological perspective. The Scarecrow Press.

- Savolainen, R. & Thomson, L. (2021). Assessing the theoretical potential of an expanded model for everyday information practices. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 73(4), 511-527. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24589

- Schatzki, T. R. (2002). The site of the social: a philosophical account of the constitution of social life and change. Pennsylvania State University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780271023717

- Seidman, I. E. (1991). Interviewing as qualitative research: a guide for researchers in education and the social sciences. Teachers College Press.

- Sonnenwald, D. H. & Iivonen, M. (1999). An integrated human information behavior research framework for information studies. Library and Information Science Research, 21(4), 429–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(99)00023-7

- Talja, S. (1997). Constituting 'information' and 'user' as research objects: a theory of knowledge formations as an alternative to the information man-theory. In P. Vakkari, R. Savolainen, & B. Dervin, (Eds.), Proceedings of an international conference on information seeking in context, Tampere, Finland, August 14-16, 1996. (pp. 67-80). Taylor Graham.

- Talja, S. & Hansen, P. (2005). Information sharing. In: A. Spink & C. Cole (Eds), New directions in human behaviour (pp. 113-134). Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-3670-1_7

- Talja, S. (2018). Science and Technology Studies. In J. D. McDonald & M. Levine-Clark (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences. CRC Press.

- Thomson, L. E. A. (2018). "'Doing' YouTube": information creating in the context of serious beauty and lifestyle YouTube. ProQuest LLC. (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Graduate School dissertation)

- Van Leeuwen, T. (1999). Speech, Music, Sound. Red Globe Press London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-27700-1

How to cite this paper

Appendix 1: Participants’ channel data

| Participant | Subject Area | Channel Start date | No of videos (24/11/21) | Subscribers (24/11/21) | Views (24/11/21) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holly | Film & Stage combat; costuming; film & TV reviews | Apr 2011 | 321 | 343K | 41,310,144 |

| Erasmus | Academic, nonsectarian study of religion | Mar 2013 | 169 | 389K | 31,685,637 |

| Emmeline Pankhurst | Historical costume reconstruction; historical costume film & TV reviews | Nov 2012 | 108 | 1.21M | 82,826,985 |

| Brock Yates | Exotic car stories & history | May 2016 | 1,210 | 1.49M | 505,060,481 |

| David Stirling | Military aircraft; military history | Aug 2016 | 225 | 43.1K | 10,419,381 |

| Francis Bacon | Ancient and medieval warfare; historical european martials arts | Feb 2007 | 677 | 1.18M | 253,393,667 |

| Gustav Klimt | Analysis of famous works of art | Apr 2020 | 26 | 583K | 15,136,047 |

| Fritz Duquesne | History storytelling through animation | Dec 2011 | 75 | 208K | 21,089,611 |

| Susie Corkin | Psychology, neuroscience and self-development | Aug 2013 | 237 | 588K | 36,182,305 |

| Erik Bloodaxe | History & archaeology; re-enactment & costume making; historical | May 2014 | 84 | 35.5K | 1,492,897 |

| Alice Wolf | Medieval and early modern history | Jun 2018 | 171 | 92.1K | 6,651,411 |

| Hatshepsut | Archaeology | Nov 2015 | 92 | 4K | 200,812 |

| Gabriel Legg | Etymology of names using animation | Nov 2015 | 482 | 315K | 48,993,099 |

| Hannah Glasse | Dessert making; viral video debunking; critique of content factories | Apr 2011 | 472 | 4.8M | 835,185,777 |

Appendix 2: Interview guide

My study aims to explore the information practices of YouTubers in making content for their channel. I’m interested in how you acquire the information you need about the topics of your videos, how you’ve developed the practical skills you need and how you learn about and use feedback from your audience.

I’ve asked you to take part because I watch and enjoy your channel and I appreciate the knowledge and skills you bring from making your content. The basic premise of this is that you are the expert and I’d like to learn from you!

Your participation in the study is anonymous. No one but me will have access to the interview recordings and your identity will be protected by a pseudonym. I feel it appropriate that you choose your pseudonym rather than me. Perhaps you might like to choose the name of an historical figure related to the topic of your channel or a favourite fictional character.

How did you become involved in making YouTube content?

How would you describe your YouTube channel?

Could you tell me a little bit about your own background and the ways in which that has helped you?

What skills and knowledge have you needed to develop to make your content? How have you gone about acquiring them?

Your channel ranges across a range of topics, how do you choose the topics for your videos? How do you go about researching them?

How long does it take you to develop a video from initial idea to upload?

Who do you see as the audience or audiences for your videos?

What data does YouTube provide you with about your audience, views etc.? How do you use it?

How would you describe your relationship with YouTube?

Are you in contact with other YouTube content creators, either professionally or socially?

If you are, how would you describe your relationship/s? How do they impact your own content creation practices?

Related to the above, one research technique I use is called ‘snowball sampling’ where I ask whether there are any people you know who you think would be good participants for the study?

What other content creators outside your circle do you think I should talk to?

Based on your greater knowledge of YouTube content creation, what questions do you think I should have asked you but didn’t?

Thank you for taking the time to share your insights with me!