For the win! Information needs in discourse of board gamers’ online communities

Anna Mierzecka and Marcin Łączyński

Introduction. As an essential part of the human experience with numerous social benefits, serious leisure is the phenomenon that has received attention in information behaviour research. Our study aims to contribute to this field by exploring board gamers’ communities’ information practices on social media sites

Method. In our research, we adopted collectivist approaches, and the empirical part of the study was conducted as a quantitative content analysis. We examined the three most active board game Facebook groups, one for each language: English, French and Polish.

Analysis. The final dataset included N=764 posts. Each post from the sample was described with 47 variables, 23 of which were based upon the codebook of question topics.

Results. The information needs expressed in the form of the online questions were in overwhelming part related to the purchase intentions, less frequently concerned tactic knowledge. The distribution of replies between topics and groups in a different language showed visible differences between each group.

Conclusions. Although this type of hobby includes both collectors’ and practitioners’ practices, the information presented in online discourse is dominated by those specific to collectors. Both information-seeking and sharing activities proved that board gamers’ online communities form a very information-rich social world.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2203

Introduction

The history of research on information behaviour demonstrates a shift from studies concentrated on science and engineering personnel and materials to, initially, social science and humanities, and then to other than academic or work-related areas of life. Notably, a significant impact was made by Chatman’s study on the information-seeking behaviour of low-income people (Chatman, 1991). The general approach was remarkably extended by Dervin’s sense-making theory (Dervin, 1992) and Savolainen’s Everyday Life Information Seeking (ELIS) theory (Savolainen, 1995) – both have become the conceptual framework for a new type of research. Despite the wide range of the studies covering different areas of human information-related life (i.e. homeless parents (Hersberger, 2001), adolescents making career decisions (Julien, 1999) or immigrants’ information needs (Fisher, Durrance, and Hinton, 2004)), still, they were some significant gaps in the research. Kari and Hartel (2007) paid attention that negative perspective dominates in information research. As a result, we might observe a focus on ‘lower things in life, which are (emotion- or motivation-wise, for example) experienced as neutral or even negative and often also as superficial phenomena’ (Kari and Hartel, 2007, p. 1132). They emphasised the importance of pleasurable and profound activities, which they called ‘higher contexts’. They argued that ’higher things’ which make human life meaningful, shape our very identity, and prevent mental disease form an essential realm of inquiry. Since then, leisure as a very rich and diverse topic has become the object of many studies. Our research aim is to contribute to this knowledge area.

Our goal is to explore the community's information practice that has not been the object of the study in the information behaviour vein: board game players. To our knowledge, no study has yielded this topic, and its significance is apparent: American Library Association highlights games’ entertaining, informational and educational benefits and recommends bringing them to the public, school and academic libraries as fitting their mission (American Library Association, n.d.). As we will show later in the article, the board games are classic serious leisure examples, and still, they involve specific and distinct patterns of information behaviour.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we present a review of earlier studies on the serious leisure and board game community. We end this section with an introduction to specific research questions we investigated. Second, we describe the methodology of the empirical study and the data collection methods. The following section depicts and discusses the study results, and the final section concludes the article and makes recommendations for future research.

Theoretical background

Serious leisure as a concept

Notion serious leisure came from sociology and was initially coined by Robert Stebbins in 1982, who developed it as an interdisciplinary concept.

'Serious leisure [...] is profound, long-lasting, and invariably based on substantial skill, knowledge, or experience, if not on a combination of these three' (Stebbins, 2001, p. 54).

Serious leisure is opposed to casual leisure activity, which is an intrinsically rewarding and relatively short-lived pleasure. The main difference between those two lies in the fact that casual leisure does not require any special knowledge or skills acquisition. On the other hand, serious leisure needs not only knowledge and competencies but sometimes even dedication to develop proficiency. Moreover, it also provides the feelings of identification with the community, which share similar goals, problems, values and experiences. It is the reason why Stebbins associated serious leisure with another sociological concept social world: a community held together by shared interest. What is important, the social worlds have no formal boundaries, and it is possible to belong to more than one. Three types of serious leisure participants are distinguished, amateurs who participate in similar activities as professionals but in a different way and volunteers who willingly help others for a combination of personal and altruistic reasons and hobbyists. The last type, the most interesting from an information behaviour research perspective, hobbyists, in turn, might be categorised into five subclasses: collectors, makers and tinkerers, activity participants, competitors in largely non-professionalised sports and games and liberal arts enthusiasts (Stebbins, 2001).

Serious leisure in information behaviour studies

Although information human behaviour researchers have widened the scope of the interest outside of academic and work contexts, initially, the studies in the realm of leisure activities were infrequent. An example of such early research is Ross’ (1999) study of reading-for-pleasure as a hobby and Kari’s (2001) examination of people’s need for paranormal information. In the vein of those research breakthrough publications were Hartel’s works. In the article The Serious Leisure Frontier in Library and Information Science (Hartel, 2003), she indicated how essential serious leisure is from the perspective of information behaviour research. As she noticed, the participants typically follow a sequence: beginning, development, establishment, maintenance, and decline. The first two stages are focused on learning, the middle on polishing the skills to achieve mastery, and the last one involves a deterioration of interest. Consequently, at least four stages focus on significant personal effort to acquire knowledge or skill and take place in information-rich social worlds. Together with Kari (Kari and Hartel, 2007), they developed the concept of serious leisure in relation to the phenomena of lower and higher things in life. As they stated, ‘currents trend of analysing how information helps in solving problems is therefore not enough’ (Kari and Hartel, 2007, p. 1143), and serious leisure, addressing the profound and pleasurable aspects of life, is an essential part of human experience, should not be neglected in the research.

This call did not remain unanswered; the diversity of studies in the area is outstanding. Prigoda and McKenzie (2007) studied information behaviour of public knitting group, Case (2009, 2010) analysed coin collectors’ decision-making process, rubber duck collecting was the research interest of Lee and Trace (2009), Cox, Clough, and Marlow (2008) explored information behaviour of amateur photography in the social media, Chang (2009) backpackers’, Gorichanaz (2015) ultrarunners’, Fulton (2017) urban explorers' and Mansourian (2021) examined the joyful aspects of information seeking and sharing in the context of serious leisure. Those examples do not complete the list. Recently, a dense literature review in this scope was done by Mansourian (2020). His findings are in line with Kari and Hartel (2007) statements about serious leisure as an essential part of human experience and its social benefits, among others, development of social capital, feeling of belongingness, social inclusion, reduction of everyday life stress and self-confidence increase. Regardless of the type of activity, the participants are engaged in information practices, including information seeking, serendipitous encounters with information, evaluating, using, sharing, disseminating, monitoring, and producing information. Literature review gave Mansourian the basis to propose a categorisation of serious leisure activities into three clusters such as (1) intellectual pursuits, (2) creating or collecting physical objects, materials or products and (3) experiential activities. Accordingly, the participants can be included in three groups: appreciators, producers or collectors, and performers, each with its own priorities and source preferences. This typology reflects better information practices than earlier Stebbins’ categorisation. Mansourian summarised the serious leisure state-of-art:

'(...) this is still an emerging field of research mainly dominated by qualitative methods and more studies need to be done with mixed method and quantitative approach to validate the growing knowledge with larger samples and broader contexts' (Mansourian, 2020, p. 26).

Board gamers community as a research field

The board gamers community, defined as fandom, is a relatively new research field. In recent years, some researchers put more attention to this group (Booth, 2017; 2021, pp. 101-108; Woods, 2012, pp. 120-145) as the renaissance of interest in analogue board games became more evident as a trend (Arnaudo, 2018, pp. 154-189; Woods, 2012). Researchers in this field divide board games that are currently played into three major segments (Arnaudo, 2018, pp. 17-20; Parlett, 2018):

- Classical games - games that are part of humanity's cultural heritage that have no clear authorship attributable, and their basic versions are not a property of any company or organisation;

- Mass market games - those titles are owned by specific, usually large multi-brand companies and organisations and are marketed to the mass audience with means of mass advertising and distributed in large retail chains (traditional and online);

- Hobby games - proprietary titles designed and manufactured by smaller companies, focused on innovative gameplay and distributed by specialised shops (online and traditional) and through other means (in fairs, conventions, etc.).

The modern board game fandom that constitutes our research field consists of the players and collectors of the games solely from the third segment. What is important in the light of serious leisure literature is the fact that hobby game fans are often at the same time collectors and players/performers, which makes them impossible to classify into only one category both in Stebbins’(2001) and Mansourian’(2020) typology. It is one of the reasons why is unique community and its information practices deserve the examination. To our knowledge, no study on information behaviour has yielded this topic, even though American Library Association highlights considerable social, cultural and educational games’ benefits (American Library Association, n.d.), and the presence of the board games in the library collections has already a long tradition (Moore, 1995).

The activity of board game fandom takes place in face-to-face meetings, but it also is possible to notice their increasing presence in virtual space. The online community of modern hobby board game players (and game collectors, as those groups overlap almost entirely) is centred around the online portal of boardgamegeek.com, owned by BoardGameGeek LLC, based in Dallas TX. Although a proprietary site, the portal is developed and managed almost entirely by a large fan community. The portal has its active forum, yet more daily discussion activity has shifted to Facebook discussion groups in recent years.

The main aim of this study is to explore the information behaviour of board game players. We agree with earlier studies’ observations of the ponderous social benefits of serious leisure. The communities of board gamers create information-rich social worlds, and the process of gaming simultaneously gives the experiences that support positive psychological well-being and increase social capital. Noteworthy is the fact that board gamers do not fit only one category in serious leisure typology: they are both collectors and game players according to Stebbins’s (2001) categories and collectors and performers according to Mansourian's (2020) one, which makes them an interesting research subject. Moreover, we would like to answer the Mansourian (2020) call for the research, which will include a larger sample and a quantitative approach that will allow comparing different groups of players. Taking into account that board game communities are active online, we decide to examine three Facebook board gamers groups in order to get knowledge about their information practices, especially knowledge acquisition and knowledge expression. As Case (2010) noticed, online communities of hobbyists operate a gift economy in which information is shared freely and willingly to benefit a larger good. Hence, such an exchange of information deserves exploration. Thus, the following research questions guided the study:

- What are board game players’ information needs?

- What information needs initiate information sharing?

- What might we say about the board game communities’ information practices based on the social media discourse?

Research design

In our research, we adopted collectivist (social constructivist) approaches. This metatheoretical position allows seeing information processes as embedded in a social or organisational context. Accordingly, the research focus should shift from individual knowledge structures to knowledge-producing, knowledge-sharing and knowledge-consuming communities (Talja, Tuominen, and Savolainen, 2005). In our case, we study board gamers’ as a community, not single players, and we believe that collectivist approaches will allow us to get knowledge about their information practices.

The empirical part of the study was conducted as quantitative content analysis, as defined by Klaus Krippendorff (2004, pp. 18-19). The choice of this technique implied some decisions to be made before the gathering of data.

First of all, we needed to define the units of information that would be sampled and analysed (Krippendorff, 2004, pp. 98-100). We decided on the most natural unit for analysing content on social media platforms, the post published by a user. The single post was the sampling unit and the coding unit, for which the values of descriptive variables were calculated. We decided on the census sampling method to be limited to 1 to 15 December. Thus, all posts matching the qualification rules from this time were subject to analysis. As the research was focused on information-gathering behaviour, we limited the sample to posts including direct or implied questions.

The narrowing of the range of posts was necessary, as not all discussions in the social media group for board gamers can be qualified as information-seeking behaviour. A large volume of posts falls into categories that we decided to exclude from the research:

- Presentation of opinion or review of a game from the professional or semi-professional reviewer,

- Bragging about one's collection,

- Jokes, memes, and other board game-related humour.

Those posts were not considered in the study, as there is no clear information-seeking intention in their content, although they may perform other functions in the hobby community formation.

To acquire a sample from similar social media outlets, we chose the three most active boardgame groups, one for each language of the survey:

- Polish 'Gry Planszowe' group, with 84 thousand members (https://www.facebook.com/groups/219681251425768)

- French 'Jeux de société QC' group with 13,3 thousand members (https://www.facebook.com/groups/132851767828)

- English 'BoardGameGeek' group with 103,8 thousand members (https://www.facebook.com/groups/174292879285831/)

Each post from the sample was described with 47 variables, 23 of which were based upon the codebook of question topics, prepared after pilot research conducted from 1 to 10 November. Those variables included:

- Six variables describing access date and time, verification date and time, and link to identify each post;

- One variable to explain the usage of graphics in the post (binary)

- Sixteen variables described two measurements (initial and after one week) of reaction to the post, which included the number of each type of seven reactions available in Facebook's interface and the number of comments (ratio);

- Twenty-three variables describing the topic of the post (binary);

- One variable describing the emotional tone of the post (nominal).

Posts that were qualified for the analysis were coded independently by two researchers (both know Polish, English and French). Then the Intercoder Reliability (Krippendorff, 2004, pp. 245-248) was calculated for the topic variables based on two measures:

- Percentage of agreement between coders: 94,6% agreement was reached;

- Cohen's Kappa: 0.731 - substantial agreement (Cohen, 1960)

Then, a discussion between researchers was conducted for the final analysis to settle on final, authoritative coding. The result of this discussion was a dataset used for further analysis.

The final dataset included N=764 posts (185 in English, 229 in French, 350 in Polish). To interpret this data, we must also acknowledge the context of each group. The group in English is a de-facto international group affiliated with the boardgamegeek.com portal. It includes significant activity, but a large volume of English-speaking players (especially those connected to the hobby for a longer time) are still using the boardgamegeek.com forum. Thus, we may assume that this group includes more casual English-speaking players from various countries. The Polish group is the primary discussion board for boardgame players in Poland, as the minority of Polish players use the boardgamegeek.com forum. The language barrier implies that most group participants are native poles. The French group is dedicated to the Quebec community. Still, it is the most active discussion-oriented group in this language (as opposed to many groups in French that serve as second-hand games markets), so it also gathers a substantial community of French-speaking players from outside Quebec. The groups that were the subject of research differ in size (as mentioned before) and in factors such as general daily activity and interest of their participants in topics covered in this research (which impacts the number of posts collected from each group). Their characteristic certainly can impact the conclusions from the study, and thus we tried to avoid this influence at every stage of the study, or at least control its impact. In the first section of the research concerning question types, we decided to use the relative measure (% of questions classified in a particular category), which as a comparison, is immune to the negative impact of group variability. In the second part of the research, we decided to use the raw information about the reactions to the question, as this number is dependent both on the group size and group relative activity, where the French group is a significant outlier, as it has the largest response rate albeit being the smallest one, which makes any other relative measurement impractical and could seriously bias the data visualisation. This problem is discussed in more detail in the section related to the information-sharing activity.

Tables with detailed data and a codebook with categories' explanations have been included in the appendix.

Findings and discussion

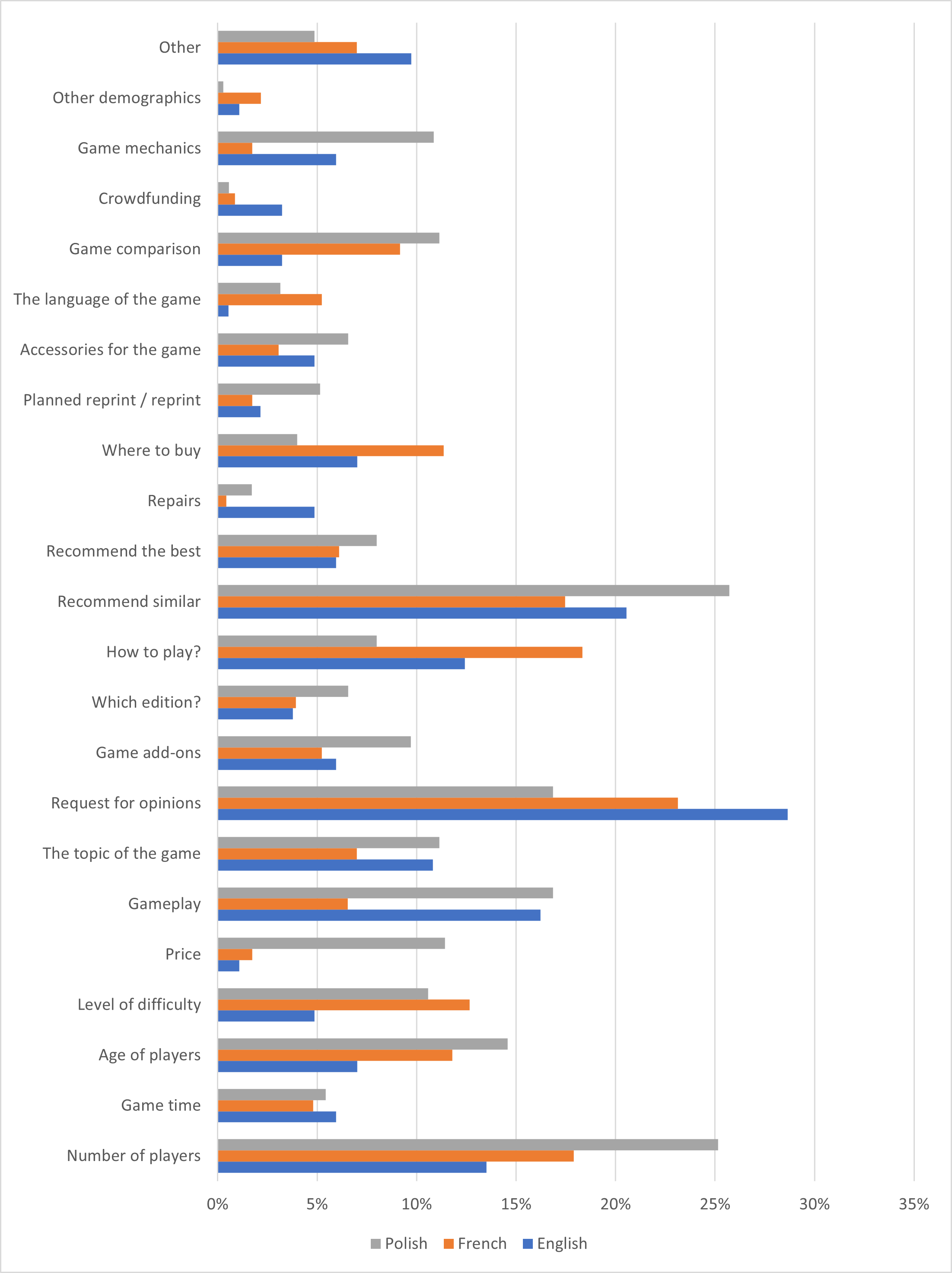

The content analysis approach gave the chance to examine authentic questions asked by game players to their online communities, which allowed to draw conclusions about their information needs. The first tendency we might observe is that the overwhelming majority of questions concern requests for recommendations to purchase a new game. There are only two exceptions: asking for advice on How to play and Repair damaged games. While repairing was not a popular topic, the request for advice on how to play was one of the most popular topics of the inquiry (8 % PL, 18.3% FR, 12,4% ENG), although the differences between the countries are visible. Apparently, Polish gamers less often use the Facebook community to seek counsel than their French-speaking colleagues (second the most popular type of questions for the FR community). Finding the reasons for differences between the countries needs further inquiries, but those results show that information needs on social media sites differ between the communities.

Nevertheless, the results, in general, are pretty surprising for the communities, which we might call both performers and collectors according to Mansourian's (2020) typology. As he stated, ‘Knowledge sharing in some SL environments such as between performers is mainly focused on tacit knowledge about specific tools and techniques’(Mansourian, 2020, p. 25). Meanwhile, the information needs expressed in the form of the online questions are in overwhelming part related to the purchase intentions, which is typical for communities of collectors. We might just suppose that in such a hobby as board games, the performance techniques needs often depend strongly on the context, and the answer is immediately required (during the game). The situation when there is a need for more general tactic knowledge is less frequent in examined online groups.

Regarding questions related to the purchase intentions, the two most popular questions belong to the code Recommend similar (PL 25.7%, FR 17.5%, ENG 20.5%) or Request for opinions (Pl 16.9%, FR 23.1%, ENG 28.6%). Recommend similar means the request for recommendations of the game similar to the game mentioned in the post. This kind of post is typical for the users who have experience with game boards, but it is not wide: they know some games, but they do not know the community jargon to precisely describe their needs. This category was the most popular question among Polish gamers, and Request for opinions was sought-after among the French and English-speaking gamers. Request for opinions includes the name of the particular game and the appeal to share players’ knowledge. Both of the mentioned posts were open requests intended to get to know the experience of other players. The general form (which often was so simple as the question ‘what do you think about/ what are your experience with?’) might suggest that their function was both informative and social: to maintain the bond with the communities. The general, exploratory character of those questions is noteworthy because, according to the observation of Skov (2013), it is not typical behaviour of the community of collectors. Examining the collectors and liberal arts enthusiasts, he observed: ‘The identified information needs were surprisingly well-defined known item needs and only a few exploratory information needs were identified’ (Skov, 2013).

Another interesting finding is related to the posts where players characterised their game circle: they need information about the game for the specific Numbers of players (PL 25.1%, FR 17.9%, ENG 13.5%) or players of specific Age (PL 14.6%, FR 11.8%, ENG 7.0%). This kind of post often includes also information about the type of relationship between players (i.e. friends, family, co-workers). This type of personal information sharing maintains social bonds and helps achieve a sense of community (Prigoda and McKenzie, 2007, p. 109). It is visible that such needs were important, especially for Polish players, quite important for the French ones, and of relatively lower significance for the English-speaking community.

The noteworthy difference we might observe regarding the Price of games: this attribute was essential only for Polish gamers (probably the game prices are for them relatively high) and rarely mentioned by other communities (PL 11.4%, FR 1.7%, 1.1%).

The other results, which show the clear difference between the examined groups, concern the manner of playing the games and are usually related to the more advanced knowledge of players. In our coding schema we distinguished three types of them: Gameplay (PL 16.9%, FR 6.6%, ENG 16.2%), The subject of the game (PL 11.1%, FR 7.0%, ENG 10.8%), Game mechanics (PL 10.9%, FR 1,7%, ENG 5.9%). The last category includes the special jargon, which usually is used by more experienced players. We noticed that the French community differs from others, which may imply that those players are generally less experienced.

Overall, in line with previous studies, our findings demonstrated strong relations between information needs and the collected objects. As Lee and Trace (2009, p. 633) stated: ‘it is almost impossible to extricate information needs from object needs. Object needs are the driving force for most collectors, but object needs spawn information needs’.

What might we say about the board game communities’ information behaviour based on the social media discourse?

As a second part of the analysis, we wanted to see whether the topics of the questions form any meaningful pattern that would allow the identification of potential informational needs of online discussion participants. To do this, we applied a k-modes clustering algorithm (Chaturvedi, Green, and Caroll, 2001) to the set of binary variables describing the content of the posts. We tested several clusters and clustering iterations options and finally settled on eight clusters and ten clustering iterations as an optimal solution. We identified the number of posts classified as part of it and variables that defined the cluster for each cluster. The interpretation of this result was conducted based on Stebbins's ( 2001) concept of information needs in serious leisure and Mansourian's (2020) typology of information practices typical to the hobby community. For each segment, we included its classification to the primary category in Mansourian's typology and, for some, a secondary classification. The primary classification was derived from the main function of the post, while the second identified the context of the question. For example, a community member that asked about the best game to buy for a game night with his colleagues was interpreted primarily as a collector, as the primary function of the post was the aggregation of opinion in the shopping process, but the secondary context also implied the experiential activity.

| Cluster | Number of posts | Variables | Interpretation – function of the question | Mansourian’s type of activity (primary (p) and secondary (s)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 95 | q13 - Recommend similar q1 - Number of players q6 - Gameplay | Getting a recommendation based on the preferred style of gameplay and examples of one’s preferred games | Collecting (p), Experiential activity (s) |

| 2 | 159 | q8 - Request for opinions | Confirming or changing the purchase intent for one particular title | Collecting (p) |

| 3 | 60 | q10 - Which edition? q22 - Game comparison | MConfirming or changing the purchase intent for a narrow selection of titles | Collecting (p) |

| 4 | 49 | q16 - Where to buy | Identifying a shop to purchase a particular game | Collecting (p) |

| 5 | 25 | q13 - Recommend similar q26 - Game mechanics q7 - The topic of the game | Getting a recommendation based on preferred mechanics, the topic of the game and examples of one’s preferred games | Collecting (p), Experiential activity (s) |

| 6 | 101 | q1 - Number of players q3 - Age of players | Getting a recommendation based on one’s playing group composition (size and demography of the group) | Collecting (p), Experiential activity (s) |

| 7 | 11 | q6 - Gameplay q26 - Game mechanics q4 - Level of difficulty | Getting a recommendation based on preferred gameplay, game difficulty and mechanics | Collecting (p), Experiential activity (s) |

| 8 | 264 | Other | Other, not classified in previous segments | NA |

| N=764 |

For all seven meaningful segments identified in the analysis, collecting was the primary activity related to the identified clusters of the posts. As those posts constitute 65.4% of the sample in the study, we may assume that the information needs associated with collecting are the most important ones when speaking of board gamers' activity in social media discussion groups. Yet, 30.5% of all the posts fell into the categories that had the experiential activity as a secondary activity associated with the question. This fact shows that, although the main discussions on social media of hobby board gamers are related to collecting, this collecting can be very often viewed as a part of the process leading to the experience of play. Thus, one cannot defend the argument of board gamers being solely a group of collectors.

We can also clearly arrange the identified segments based on how much information the person asking the question needs and where they are in the decision-making process:

- Very open to arguments, looking for any games that fit their preferences (segments 6 and 7

- Open to options that fit their taste, but with some games already treated as a benchmark (segments 1 and 5)

- Requiring aid in choosing a game from a narrowed set, or perhaps a binary choice between game A or B (segment 3)

- Looking to confirm or change their purchase intent of one selected game (segment 2)

- Looking for a shop recommendation when the choice of the game to add to their collection is already made (segment 4).

Furthermore, the division into segments gave us the opportunity to reflect on the nature of the board game as a kind of entertainment. Are we rightly looking at it as serious leisure? Or is it more of an activity seen as an intrinsically rewarding and relatively short-lived pleasure, that is, according to the definition, casual leisure? There are games in which participation does not need knowledge or competencies.

Segmenting posts that reflect group members' information needs is an excellent way to answer that question. Segment 6 shows information needs that may be appropriate for people who treat board games as casual leisure – no signs of game familiarity. On the other hand, the remaining segments reflect the information needs of people with knowledge of board games, although the level of advancement varies (e.g. segment 7 shows players advanced expertise, while segment 1 is somewhat intermediate). This indicates that the view of board games as serious leisure is accurate.

What information needs initiate information sharing?

Information-seeking activity on social media has two sides: the question and the answer. In the last part of our study, we focused on the answers to the questions. We compare the average number of replies for each post by the topic of the question and by segment. There are some visible differences between groups, although the overall pattern is similar. Before we show the graphs, there is one significant remark about the data used to compare groups. We compare the average amount of comments in each category in this part. The group size may, obviously, impact this measure, so we also calculated the distribution of the average number of comments adjusted to the size of the group (instead of the raw number of comments, we used a proportion of this number to the group size). This measurement proved to be more problematic, as it was less intuitive, and the group relative activity (instead of group size) impacted it distinctly. This made the comparison with the French group, which is very active (despite the smallest size), very difficult. Finally, we decided to use the most straightforward measure, which is easier to interpret and more intuitive.

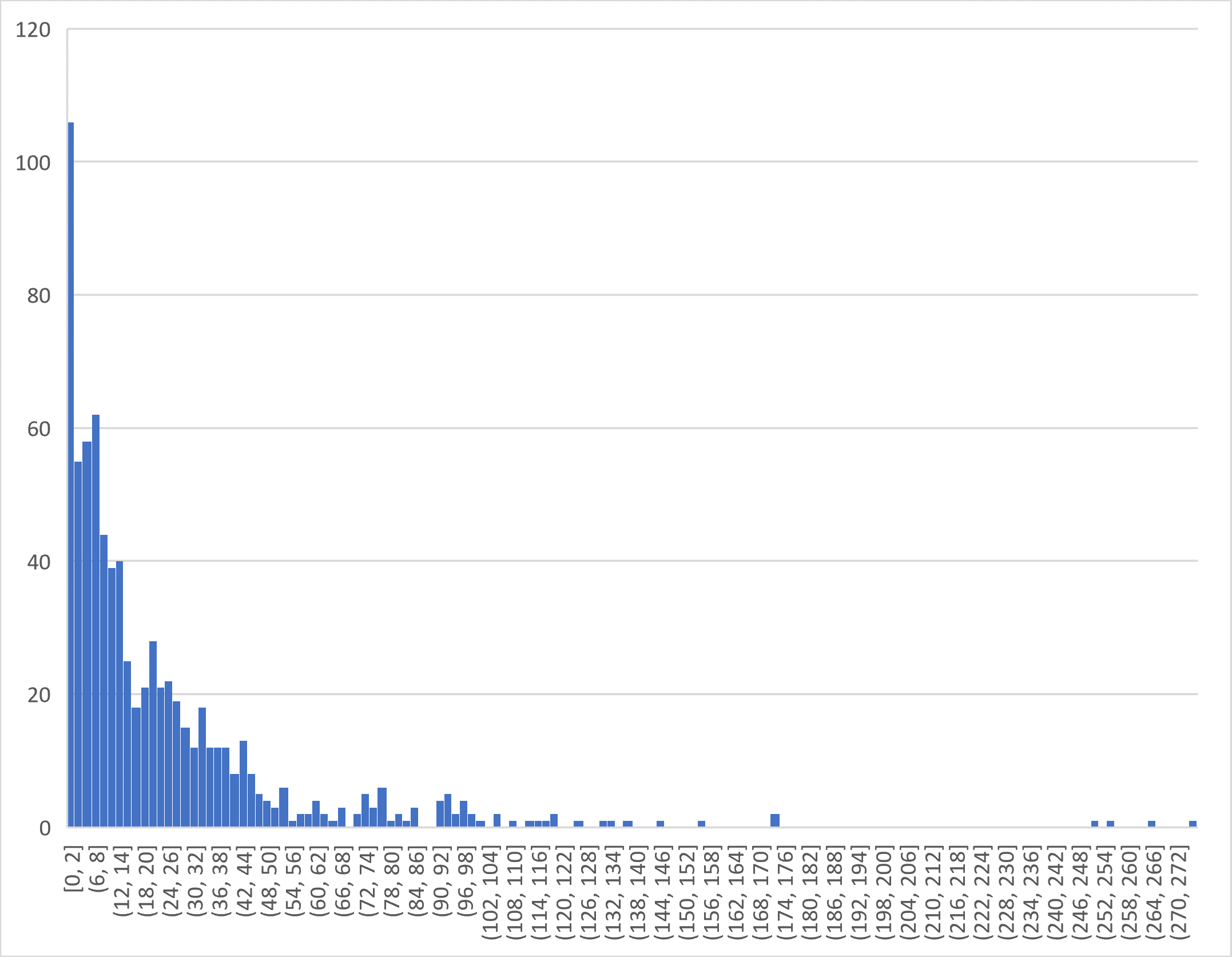

The presented distribution of comments per post shows that the vast majority of those posts get some answers (only 106 from 764 posts got 2 or fewer answers), and some of the discussions are quite lengthy and exhaustive (there's a significant part of the distribution with 20 or more replies). The overall level of response is high – 24.85 replies per post and only 38 posts (4.98%) didn't get any answer. We may assume the Facebook discussion groups may be an effective channel to acquire important information from the hobby community, which shares information willingly, in line with Case’s (2010) conclusions about the ‘gift economy’ in this community.

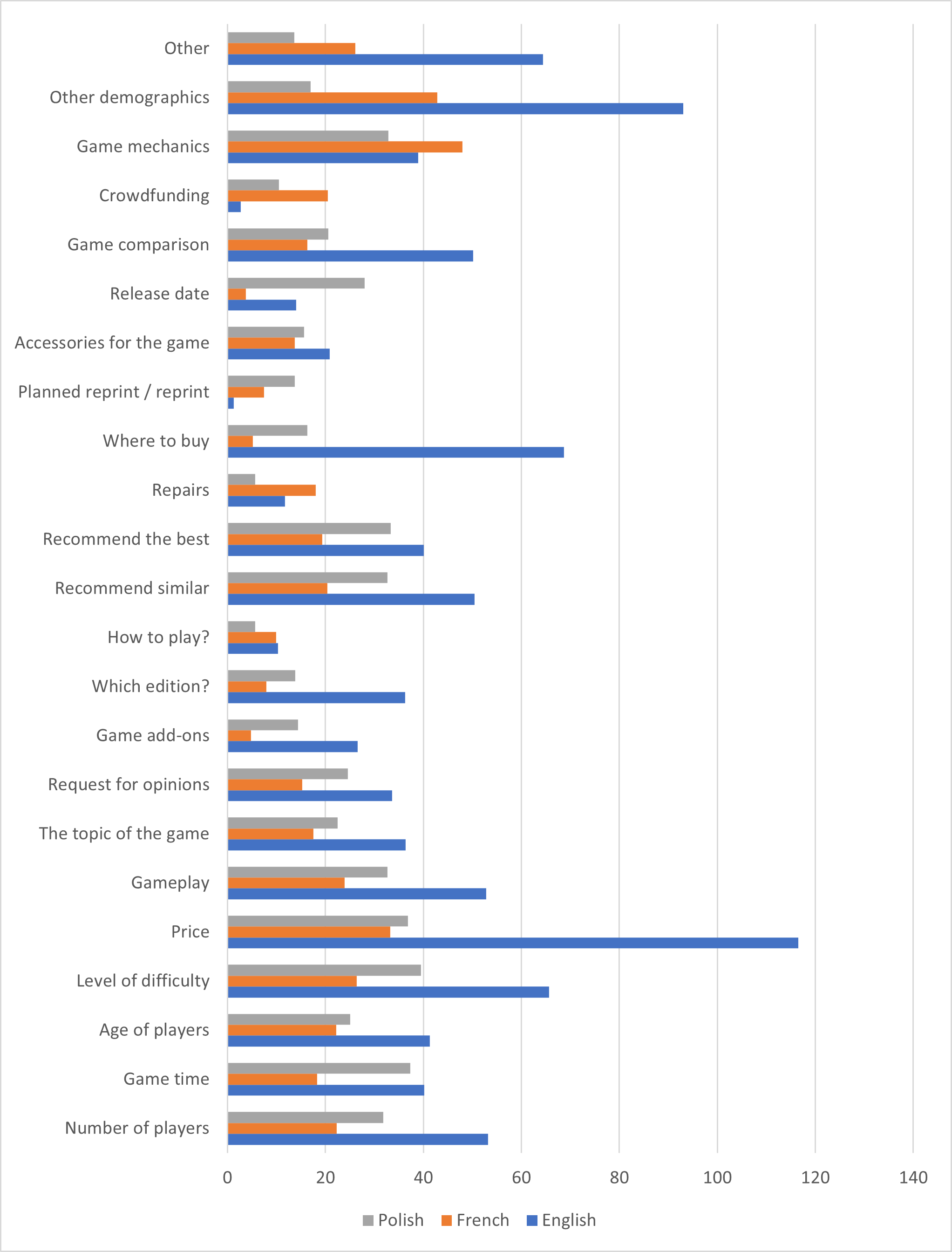

The distribution of replies between topics and groups in a different language shows visible differences. In English speaking group, the most discussed posts were those that concerned recommendations based on Price (116.5 replies on average), Other demographic traits (93 replies on average, this category mainly included questions about games best for specific gender), and shops selling board games (68.7 answers on average). In the Polish group, the most discussed posts were those that addressed Game difficulty (39.5 responses on average), Gameplay time (37.3 answers on average), and game Price (36.9 replies on average). In the French group, the questions that were most discussed concerned Game mechanics (48 replies on average), Other demographic traits (42.8 answers on average again; those questions concerned mostly gender), and the game Price (33.3 responses on average). The "how to play" questions received almost the lowest responses in every language (10.3 in English, 9.9 in French, and only 5.6 in Polish).

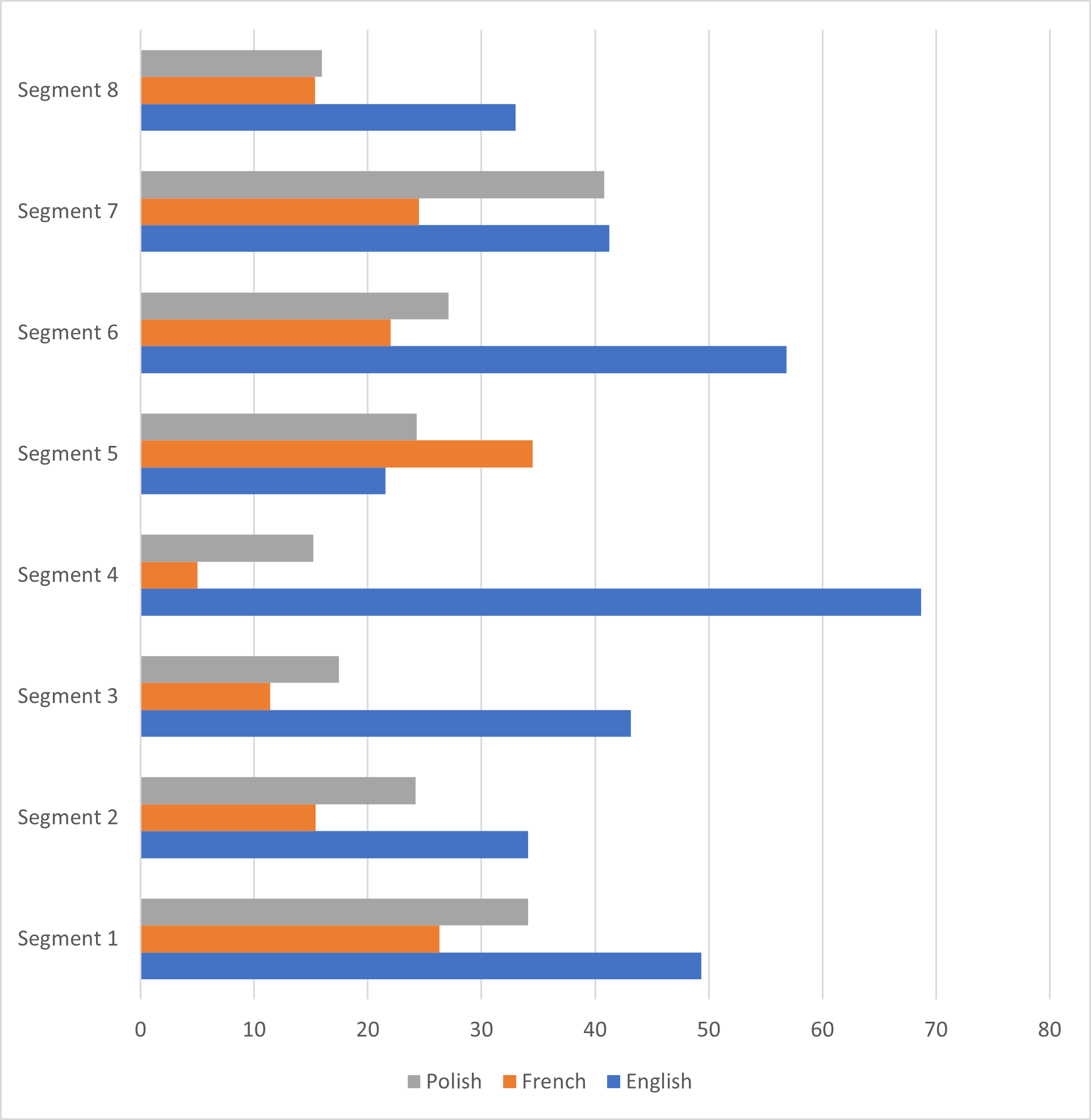

This last chart summarises the distribution of replies between segments identified in the previous part of the paper. Similar to the previous one, the chart shows a similarity between the distribution of answers in the Polish and French groups and the significant difference between them and the English-speaking group. The English-speaking group has a visibly higher response rate in segments 3 (narrow selection of titles) and 4 (where to buy), a lower response rate in segment 5 (recommendation of similar games based on topic and mechanics), and a slightly higher response rate in segment 6 (advice based on the composition of players' group). The main difference between the Polish and French groups is located in segment 5 (more responses in the French group concerning the recommendation of similar games based on topic and mechanics) and in segment 7 (more responses in the Polish group concerning the proposal of games based on kind of gameplay, difficulty, and mechanics).

Based on the analysis of replies, we can conclude that the questions posted in discussion groups for board gamers effectively satisfy one's information needs associated with the hobby. Most of the inquiries received a significant number of answers. The scope of the discourse visible in the answers gravitates to the board game buying and collecting as the primary activity visible in the social media groups, as the few gameplay questions get one of the lowest response rates. The biggest difference between the groups in different languages is visible in the English-speaking group. In this discussion group, there is a significantly larger response for posts with questions focused on the near-buy decision-making process (about choosing one of the narrow sets of previously selected games or choosing the best shop to buy games).

In general, the overall high level of responses is in line with earlier studies (Case, 2010; Lee and Trace, 2009). As shown, the main information exchange in examined groups is typical of collectors' behaviour. Lee and Trace (2009, p. 634) noticed that the primary role of information for this group is to help build interpersonal connections, and Case developed this constatation even further: ‘the primary benefit is a cumulative contribution to sensemaking regarding the problem and hand and secondarily a bit of emotional support-knowing that one is not alone and that others are willing to help’(Case, 2010)A similar phenomenon is observed in our study.

What essential questions concerning board game players' information behaviour remain without answer?

This question might seem naïve since no study would answer all the questions about the information behaviour of examined users. We considered such an issue in order to highlight the topics we expected to gather information about, and we were not able to obtain the data. First, we hoped to find information about the gamers' level of mastery in the posts. As Hartel (2003) noticed, the participants' engagement and skills development follow the general sequences. We thought the gamers' posts would include the hints that allow us to prepare categorisation according to expertise level. Meanwhile, as the posts were mainly related to purchasing needs (typical for collectors) and not with tactic knowledge (typical for performers), we obtained very slight indications, primarily based on the type of used language (common / jargon), about mastery level. It was not enough to define what kind of participants take part in online discussions.

Second, we assumed that in gamers' posts, we would find the reference to other sources of information, and we would be able to get knowledge of what they see as preferable or credible information channels or sources. We know about different online sites like BoardGameGeek LLC, where users exchange information about board games. Still, in the examined sample, we did not find any mention of it, so we cannot say if it is the information source used. In general, the posts very rarely contained references to any other information sources (a few recommendations of websites and video blogs) – for examined communities (at least based on their posts), the main sources of information were the knowledge shared by other members of the Facebook group.

Limitations of the study

We decide to choose quantitative content analysis of online discourse in order to compare the information behaviour of different board game players during the same period and show some tendencies. An apparent limitation of the method is the lack of possibility to examine such vital questions as the broader context of players’ situation, their motivations to share the information, their positioning in the group and how they evaluate and use the information they obtain during online interaction. We find those issues essential, and using the mixed methodology, we want to examine them in further studies. Another limitation of the study is the fact that our study did not include board gamers’ information behaviour outside the online space.

Conclusion

To wrap up the findings and the discussion, we might say the online space chosen to examine the board gamers’ information behaviour proves to be a very information-rich social world. The short period of two weeks was enough to observe a wide range of information activities: numerous questions and even more numerous answers and comments. Results demonstrate that although this type of hobby includes both collectors' and practitioners' practice, the information presented in online discourse is dominated by those specific to collectors. This tendency was common in the case of the three explored groups regardless of the language they used. It was also possible to find other similar observations like the requests for opinions about a specific game or to indicate similar ones. They are also apparent variations between the communities, especially in the replies to the posts: different topics inspired active information sharing. Furthermore, we noticed that the type of posts that rarely appeared in the feed (i.e. Price in the English-speaking community) afterwards got a lot of attention in comments. To conclude, the board game players form a social network with diverse and developed information activities related to both information-seeking and sharing.

The division into segments presented in the article allowed for an interesting illustration of the types of players' information needs based on queries' characteristics. It also shows that in the case of activities whose nature - serious or casual leisure - may be debatable, the analysis of query patterns, as was done in the article, may resolve the doubts.

This research provides the argument that systematic content analysis can also be a valuable tool in information behaviour research. Analytical approach to the communication content, coding of the actual questions and answers provided by participants of online communities, and the possibility of quantitative analysis of results are significant advantages of this method. This approach also provides a good framework for validating various theoretical assumptions about information behaviour, as the codebook used during the analysis could be well adjusted to resemble a particular theory or model.

The high level of activity in the observed groups provides the basis for a practical recommendation: the visible high interest in games can be easily used by libraries (in many cases, this is already happening), especially those that want to function in communities as a third place. Looking at the nature of the questions asked, it would be particularly promising to organise sessions targeted at specific age groups or thematically profiled, e.g. criminal riddles or strategy.

The image obtained by exploring online information practices is only part of the whole picture. The major part of this group activity takes place outside the online space. Examination of social media groups gave us an extraordinary chance to conduct a comparison of different groups’ discourse. Although, further study should, according to Mansourian (2020) call, use the mixed methodology and embrace the information behaviour in both virtual and actual worlds.

About the authors

Anna Mierzeckais an Associate Professor at the University of Warsaw, 26/28 Krakowskie Przedmiescie Street, 00-927 Warsaw. She received her PhD from the University of Warsaw, and her research interests include information behaviour, academic libraries and information literacy. She can be contacted at anna.mierzecka@uw.edu.pl

Marcin Łączyński is Ph.D. candidate at the University of Warsaw, 26/28 Krakowskie Przedmiescie Street, 00-927 Warsaw. His research interests include content analysis, fandom research, and tabletop games. He can be contacted at m.laczynski@uw.edu.ply

References

- American Library Association. (n.d.). Games in Libraries: Obstacles and Challenges. https://games.ala.org/games-in-libraries/ (Internet Archive)

- Arnaudo, M. (2018). Storytelling in the modern board game: Narrative trends from the late 1960s to today. McFarland.

- Booth, P. (2017). Board Games as Fans. In M. A. Click & S. Scott (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom. Routledge.

- Booth, P. (2021). Board Game as Media. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Case, D. O. (2009). Serial Collecting as Leisure, and Coin Collecting in Particular. Library Trends, 57(4), 729 - 752. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.0.0063

- Case, D. O. (2010). A model of the information seeking and decision making of online coin buyers. Information Research, 15(4). http://informationr.net/ir/15-4/paper448.html (Internet Archive)

- Chang, S.-J. L. (2009). Information research in leisure: Implications from an empirical study of backpackers. Library Trends, 57(4), 711-728. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.0.0062

- Chatman, E. A. (1991). Life in a small world: Applicability of gratification theory to information-seeking behavior. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(6), 438-449. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199107)42:6 <438::AID-ASI6>3.0.CO;2-B

- Chaturvedi, A., Green, P. E. & Caroll, J. D. (2001). K-modes Clustering. Journal of Classification, 18(1), 35-55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00357-001-0004-3

- Cohen, J. (1960). A Coefficient of Agreement for Nominal Scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104

- Cox, A. M., Clough, P. D., & Marlow, J. (2008). Flickr: a first look at user behaviour in the context of photography as serious leisure. Information Research, 13(1), 13-11. http://informationr.net/ir/13-1/paper336.html (Internet Archive)

- Dervin, B. (1992). From the mind’s eye of the user: The sense-making qualitative-quantitative methodology. In J. Glazier & R. Powell (Eds.), Qualitative research in information management (pp. 61–84). Libraries Unlimited.

- Fisher, K. E., Durrance, J. C., & Hinton, M. B. (2004). Information grounds and the use of need-based services by immigrants in Queens, New York: a context-based, outcome evaluation approach. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 55(8), 754–766. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20019

- Fulton, C. (2017). Urban exploration: Secrecy and information creation and sharing in a hobby context. Library & Information Science Research, 39(3), 189-198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2017.07.003

- Gorichanaz, T. (2015). Information on the run: experiencing information during an ultramarathon. Information Research: An International Electronic Journal, 20(4). http://informationr.net/ir/20-4/paper697.html#.YfIuZX3MLAM (Internet Archive)

- Hartel, J. (2003). The serious leisure frontier in library and information science: hobby domains. Knowledge organization, 30(3/4), 228-238.

- Hersberger, J. (2001). Everyday information needs and information sources of homeless parents. New Review of Information Behaviour Research, 2, 119-134.

- Julien, H. E. (1999). Barriers to Adolescents' Information Seeking for Career Decision Making. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 50, 38-48. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(1999)50:1<38::AID-ASI6>3.0.CO;2-G

- Kari, J. (2001). Information seeking and interest in the paranormal: Towards aprocess model of information action. (University of Tampere PhD dissertation)

- Kari, J., & Hartel, J. (2007). Information and higher things in life: Addressing the pleasurable and the profound in information science. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(8), 1131-1147. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20585

- Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lee, C. P., & Trace, C. B. (2009). The role of information in a community of hobbyist collectors. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 60(3), 621-637. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20996

- Mansourian, Y. (2020). How Passionate People Seek and Share Various Forms of Information in Their Serious Leisure. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, 69(1), 17-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2019.1686569

- Mansourian, Y. (2021). Joyful information activities in serious leisure: looking for pleasure, passion and purpose. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 73(5), 601-617. https://doi.org/10.1108/ajim-01-2021-0002

- Moore, J. E. (1995). A History of Toy Lending Libraries in the United States Since 1935. (Kent State University PhD dissertation)

- Parlett, D. (2018). Oxford History of Board Games. Echo Point Books & Media.

- Prigoda, E., & McKenzie, P. J. (2007). Purls of wisdom. Journal of Documentation, 63(1), 90-114. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410710723902

- Savolainen, R. (1995). Everyday life information seeking: Approaching information seeking in the context of “way of life”. Library & Information Science Research, 17(3), 259-294. https://doi.org/10.1016/0740-8188(95)90048-9

- Sheldrick Ross, C. (1999). Finding without seeking: the information encounter in the context of reading for pleasure. Information Processing & Management, 35(6), 783-799. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(99)00026-6

- Skov, M. (2013). Hobby-related information-seeking behaviour of highly dedicated online museum visitors. Information Research, 18(4) paper 597. http://InformationR.net/ir/18-4/paper597.html ( Internet Archive )

- Stebbins, R. A. (2001). Serious leisure. Society, 38(4), 53-57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-001-1023-8

- Talja, S., Tuominen, K., & Savolainen, R. (2005). “Isms” in information science: constructivism, collectivism and constructionism. Journal of Documentation, 61(1), 79-101. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410510578023

- Woods, S. (2012). Eurogames: The Design, Culture and Play of Modern European Board Games. McFarland & Company.

How to cite this paper

Appendices

| Polish | French | English | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| q1 | Number of players | 88 | 41 | 25 |

| q2 | Game time | 19 | 11 | 11 |

| q3 | Age of players | 51 | 27 | 13 |

| q4 | Level of difficulty | 37 | 29 | 9 |

| q5 | Price | 40 | 4 | 2 |

| q6 | Gameplay | 59 | 15 | 30 |

| q7 | The topic of the game | 39 | 16 | 20 |

| q8 | Request for opinions | 59 | 53 | 53 |

| q9 | Game add-ons | 34 | 12 | 11 |

| q10 | Which edition? | 23 | 9 | 7 |

| q11 | How to play? | 28 | 42 | 23 |

| q13 | Recommend similar | 90 | 40 | 38 |

| q14 | Recommend the best | 28 | 14 | 11 |

| q15 | Repairs | 6 | 1 | 9 |

| q16 | Where to buy | 14 | 26 | 13 |

| q17 | Planned reprint/reprint | 18 | 4 | 4 |

| q19 | Accessories for the game | 23 | 7 | 9 |

| q21 | The language of the game | 11 | 12 | 1 |

| q22 | Game comparison | 39 | 21 | 6 |

| q25 | Crowdfunding | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| q26 | Game mechanics | 38 | 4 | 11 |

| q27 | Other demographics | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| q18 | Other | 17 | 16 | 18 |

| Together | 350 | 229 | 185 |

| Polish | French | English | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| q1 | Number of players | 25,1% | 17,9% | 13,5% |

| q2 | Game time | 5,4% | 4,8% | 5,9% |

| q3 | Age of players | 14,6% | 11,8% | 7,0% |

| q4 | Level of difficulty | 10,6% | 12,7% | 4,9% |

| q5 | Price | 11,4% | 1,7% | 1,1% |

| q6 | Gameplay | 16,9% | 6,6% | 16,2% |

| q7 | The topic of the game | 11,1% | 7,0% | 10,8% |

| q8 | Request for opinions | 16,9% | 23,1% | 28,6% |

| q9 | Game add-ons | 9,7% | 5,2% | 5,9% |

| q10 | Which edition? | 6,6% | 3,9% | 3,8% |

| q11 | How to play? | 8,0% | 6,1% | 5,9% |

| q13 | Recommend similar | 25,7% | 17,5% | 20,5% |

| q14 | Recommend the best | 8,0% | 6,1% | 5,9% |

| q15 | Repairs | 1,7% | 0,4% | 4,9% |

| q16 | Where to buy | 4,0% | 11,4% | 5,9% |

| q17 | Planned reprint/reprint | 5,1% | 1,7% | 2,2% |

| q19 | Accessories for the game | 6,6% | 3,1% | 4,9% |

| q21 | The language of the game | 3,1% | 5,2% | 0,5% |

| q22 | Game comparison | 11,1% | 9,2% | 3,2% |

| q25 | Crowdfunding | 0,6% | 0,9% | 3,2% |

| q26 | Game mechanics | 10,9% | 1,7% | 5,9% |

| q27 | Other demographics | 0,3% | 2,2% | 1,1% |

| q18 | Other | 4,9% | 7,0% | 9,7% |

| Variable | Format | Comment/description |

|---|---|---|

| Date of publications | dd.yy.rrrr | |

| Time of publication (CET) | hh:mm | |

| Date of publication | dd.yy.rrrr | |

| Time of publication (CET) | hh:mm | |

| Date of recording | dd.yy.rrrr | |

| Time of recording (CET) | hh:mm | |

| Code of group | A - English; F - French; P - Polish | |

| Direct link | URL adress | |

| Use of graphics in post | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | |

| LIKE - Number of reactions - first measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| LOVE - Number of reactions - first measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| HUG - Number of reactions - first measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| LAUGH - Number of reactions - first measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| WOW - Number of reactions - first measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| CRY - Number of reactions - first measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| ANGRY - Number of reactions - first measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| Number of comments - first measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| LIKE - Number of reactions - second measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| LOVE - Number of reactions - second measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| HUG - Number of reactions - second measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| LAUGH - Number of reactions - second measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| WOW - Number of reactions - second measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| CRY - Number of reactions - second measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| ANGRY - Number of reactions - second measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| Number of comments - second measurement | Number | Numeric data from the Facebook interface |

| Number of players | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | A certain number of players as a factor in choosing the game |

| Game time | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Specific game time as a factor in selecting the game |

| Age of players | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Suggested age of players as a factor in selecting the game |

| Level of difficulty | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Subjective level of difficulty as a factor in selecting the game |

| Price | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Game price (limit) one is ready to pay for a game |

| Gameplay | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | The style of gameplay (strategic, party, deductive) as a factor in choosing the game |

| The topic of the game | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | The preferred topic of the game |

| Request for opinions | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | A general request for opinions about a specific title |

| Game add-ons | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Question about best game add-ons that community members recommend |

| Which edition? | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Question about best game edition that community members recommend |

| How to play? | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Questions on how to play particular titles (about rules, interpretation of winning conditions, etc.) |

| Recommend similar | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Request to recommend a game similar to specific title or titles |

| Recommend the best | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Request to recommend the best game title for a particular occasion (party, integrational meeting, family gathering, night with friends) |

| Repairs | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Question about the best way to repair certain broken game elements |

| Where to buy | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Question about online and traditional shops that have a specific title in stock |

| Other | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Other factors important in selecting the best game |

| Accessories for the game | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Request for recommendation about game accessories (boxes, sleeves, organisers, tokens, upgrades) |

| Release date | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Question about the estimated release date of a certain title |

| Language version | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Question about particular language version of specific game or games in a specific language |

| Game comparison | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Question to compare two or more titles (with or without additional criteria of comparison) |

| Crowdfunding | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Question about crowdfunding campaigns for games |

| Game mechanics | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Particular game mechanics as a factor in choosing the game (vocabulary of mechanics from: https://boardgamegeek.com/browse/boardgamemechanic |

| Other demographics | 1 - YES; 0 - NO | Other demographics of preferred players as a factor in selecting the game |

| Emotions in post | 1 - YES; 0 - NO |

|

|

© the authors, 2022. Last updated: 2 November, 2022 |