Drivers and barriers of using online social networking technologies among people living with HIV/AIDS in Iran

Azam Bazrafshani, Sirous Panahi, Hamid Sharifi, and Effat Merghati-Khoei

Introduction. Online social network technologies have been widely used to enhance HIV prevention, diagnosis, and treatment programs; however, little is known about the current use and potential drivers and barriers of these technologies among Iranian people living with HIV.

Method. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 28people living with HIV/AIDS already using online social network technologies.

Analysis. Thematic analysis was used to analyse interviews.

Results. Results showed that the average time spent on online social network platforms was 3.5-5.7 hours daily. Peer groups and pre-existing platforms (groups) established by health care providers or community-based organisations were frequently used by people living with HIV/AIDS for communication. Seeking and sharing health information and personal experiences, staying connected with peers and care providers, and social support exchange were major drivers for using online social network platforms. Cross-posting of users or sharing irrelevant or disappointing posts, gender issues, and poor engagement of users were reported as major barriers to online social network use among respondents.

Conclusions. Our findings indicated that online social network technologies have empowered Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS, making them more connected, safe, and able to access HIV/AIDS-related information and services. Future studies are needed to investigate the feasibility and acceptability of these interventions among key populations including sex workers and injection drug users.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper940

Introduction

According to available data, approximately 75,700 people were living with HIV in Iran at the end of 2016 (Sharifi et al., 2018).It is estimated that about one-third (36%) of people living with HIV/AIDS are aware of their HIV status and referred to HIV care services for treatment (Farhoudi et al., 2022). Injection drug use is known as the primary source of HIV transmission in Iran. With an estimated prevalence of 15.2%-13.8% in 2010 and 2013, people who inject drugs continue to be among the most vulnerable populations to acquire HIV infection (Seyedalinaghi et al., 2021). However, recent evidence has emerged that displays an increasing pattern of HIV incidence among women and female sex workers (female sex workers). Sex and sexuality are often considered private and taboo topics for discussion. Sex workers do not receive social support from the community and are not screened for sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV. Therefore, female sex workers are considered the second most at-risk population for HIV transmission in Iran (Farhoudi et al., 2022; Shokoohi et al., 2016).

Prostitution and sex work are extremely illegal and stigmatised in Iran due to conservative cultural norms regarding sexual habits. Illicit drug use and illegitimate sexual practices have made HIV/AIDS a neglected and taboo subject over the years and consequently posed major challenges to successful treatment in Iran. Retention in care and adherence to antiretroviral treatments is crucial for successful HIV treatment. Yet in Iran, only 20% of Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS were engaged in medical care for treatment and only 17% were antiretroviral treatment adherent and virally suppressed (Farhoudi et al., 2022). Additionally, limited access to antiretroviral treatments, poor medication adherence, and limited access of key populations (men who have sex with men, people who inject drugs, people in prisons and other closed settings, female sex workers and their clients, and transgender people) to consistent health services and prevention programs are threatening the success of HIV prevention and control programs. Too often, Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS experience high levels of stigma and discrimination in the communities where they live. Stigma, discrimination, and criminalisation are among the barriers that prevent key populations from accessing comprehensive health services.

Internet and online social network technologies globally provide advantages for people living with HIV/AIDS to cope with the complicated nature of HIV through communication with peers and care providers, access and receiving health information, sharing health and health care data including personal experiences and social support (Chung, 2014; (Gold et al., 2011; Grosberg et al., 2013; Horvath et al., 2012; Young and Rice, 2011). Available evidence suggests the widespread use of Internet and health information seeking behaviour among people living with HIV/AIDS (Courtenay-Quirk et al. 2010; Li et al., 2013; Lwoga et al., 2017; Stonbraker et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018), and their care-providers (Horvathe et al., 2009)in most developed parts of the world. For instance, in a survey of 433 American people living with HIV/AIDS, Samal et al. (2011) showed that nearly half of people living with HIV/AIDS reported Internet and health information-seeking behaviour to seek information about HIV. Stonbraker et al. (2017) also indicated that over 77% of Dominican people living with HIV/AIDS who participated in a survey reported active health information seeking.

Emerging evidence also highlighted the feasibility, acceptability, and preference of online social network usage among people living with HIV/AIDS. A cross-sectional survey of 312 American people living with HIV/AIDS revealed a high willingness to accept and use online social network technologies for communication and receiving relevant HIV informational content (Horvathe, et al., 2012). In a pilot intervention of 41 people living with HIV/AIDS using online support groups in Nigeria, 65% of participants reported using the Internet and 64% reported using online social network sites including Facebook for interaction with other people living with HIV/AIDS, learning about HIV, and sharing socio-emotional supports (Dulli et al., 2018). Internet and online social network technologies have increasingly been demonstrated to provide people living with HIV/AIDS with valuable opportunities for access to health services, resources, information, and support required during the continuum of care. These technologies have the potential to empower people living with HIV/AIDS, not only by producing patient-centred healthcare services but by challenging the stigma and discrimination people living with HIV/AIDS are likely to encounter or affected by. Research suggests that online social network technologies are largely effective in providing social support for people living with HIV/AIDS (Chung, 2014; Courtenay-Quirk et al., 2010; Koufopoulos et al., 2016; Kremer and Kironson, 2007; Mo and Coulson, 2008, 2012; Reeves, 2001).

A substantial body of literature focusing on the application and feasibility assessment of online social network platforms also indicates the effective role of these technologies in HIV prevention, testing and diagnosis, risk reduction, and stigma elimination, particularly in developed countries including the United States, England, Canada, and China (Brown et al., 2017; Garett et al., 2016; Hailey and Arscott, 2013; Hightow-Weidman et al., 2018; L'Engle et al., 2015; LeGrand et al., 2018; Marent et al., 2018; Muessig et al., 2015; Muessig et al., 2013; Whiteley et al., 2018). Hundreds of thousands of people living with HIV/AIDS across the developed countries, sharing their concerns about the disease, have taken advantage of online social network applications and online support groups to exchange resources and support. However, existing evidence on the acceptability and application of online social network technologies among people living with HIV/AIDS in Iran and other developing countries with rather different social, cultural, and religious contexts is scarce. HIV continues to remain a social and cultural taboo in Iran and many parts of the world. The consequences of existing social and cultural taboos in vulnerable communities are wide-ranging. Socio-cultural factors can increase the risk of HIV transmission by creating barriers to access prevention methods and information. Available evidence suggests that social taboos could repress awareness and prevention of HIV, and other sexually transmitted infections.

In addition to the fact that 94.4% of the Iranian population own a mobile phone, 69.1% have access to the Internet, and 36 million (equivalent to 42.6% of the total population) active social media users (Chavoshi and Hamidi, 2019), online social network platforms have the penetration to function as a powerful and indispensable venue in promoting awareness and HIV prevention in Iran. Although there is rapid progress on the use of online social network technologies in the HIV continuum of care, little evidence has been documented on the use of these technologies by Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS. The limited understanding of online social network use patterns, platforms, motivations, and perceived barriers among people living with HIV/AIDS could limit the application and utilisation, acceptability, and effectiveness of the programs and interventions. Thus, to provide a better understanding of the potential for the application of online social network technologies and platforms, the main purpose of this study is to investigate the application of these technologies by presenting a qualitative analysis of Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS perspectives on online social network use, motivations, and barriers to communicating about HIV prevention and care. This study contributes to the existing literature in several ways by providing the first evidence on the acceptability and application of online social network technologies among people living with HIV/AIDS within a conservative culture. This study also highlights drivers and barriers to using these technologies and provides recommendations and future directions for improving the application of these technologies in the HIV continuum of care. The study findings apply to the people living with HIV/AIDS in other communities with conservative cultures across the world.

Materials and method

Study design

This study included in-depth semi-structured interviews with Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS, as part of a larger study on the health consequences of using online social network platforms among people living with HIV/AIDS conducted between October 2018 and January 2019. We recruited individuals 18 years of age and older who reported having participated in any HIV/AIDS online social networks within 6 months prior. Participants were recruited through government-sponsored health clinics and community-based organisations in Tehran metropolitan area, providing HIV control and prevention services such as vaccination, HIV testing, counselling, and risk reduction items (i.e., syringe, needle, and condom), as strictly confidential, voluntary, and free of charge. A purposive sample of 28 people living with HIV/AIDS eligible for the study was recruited from two dominant centres including Imam Khomeini Hospital and ZamZam Clinic. These centres comprise the largest proportion of target populations and most patients prefer these centres for their treatment and care. Eligible volunteers were recruited through online advertising in online social network groups. An invitation letter was posted to online group boards by group facilitators/administrators. Interested volunteers then contacted the administrators and asked them to schedule an appointment for visiting patients and conducting interviews.

Participants

Over 70% of people living with HIV/AIDS who participated in the study were recruited from Imam Khomeini Hospital and lived in Tehran metropolitan area and the rest were from communities other than Tehran. Participants had a mean age of 39.7 years. Men (60.7%, n=17), and people living with HIV/AIDS with lower levels of education (high school or below) (85.7%, n=24) constituted the greatest proportion of respondents. About half of the respondents were unemployed (46.4%, n=13) and, did not report a history of drug injection or addiction (57.1%, n=16). Sexual behaviour (53.6%, n=15) and needle or syringe use (21.4%, n=6) were the most referred sources of HIV transmission among people living with HIV/AIDS. About half of respondents were diagnosed with HIV more than ten years ago Table 1 gives an account of participants in the study and their demographic information).

| Characteristics | Frequencies | Characteristics | Frequencies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Recruitment site | Education | ||||

| Imam Khomeini Hospital | 20 | 71.4 | High school or below | 24 | 85.7 |

| ZamZam clinic | 8 | 28.6 | Some college | 1 | 3.6 |

| Residence at time of interviews | University | 3 | 10.7 | ||

| Tehran | 20 | 71.4 | Employment status | ||

| Karaj | 1 | 3.6 | Employed | 12 | 42.9 |

| Bushehr | 1 | 3.6 | Disabled/retired | 3 | 10.7 |

| Bandar-Abbas | 1 | 3.6 | Unemployed | 13 | 46.4 |

| Qum | 1 | 3.6 | History of drug injection or abuse | ||

| Kerman | 1 | 3.6 | Yes | 12 | 42.9 |

| Age | No | 16 | 57.1 | ||

| 18-20 | 0 | 0.0 | Source of transmission | ||

| 21-30 | 2 | 7.1 | Sexual behaviour | 15 | 53.6 |

| 31-40 | 16 | 57.2 | Contaminated needle or syringe use | 6 | 21.4 |

| >40 | 10 | 35.7 | Blood transfusion | 2 | 7.1 |

| Sex | Unknown | 5 | 18.9 | ||

| Male | 17 | 60.7 | Years living with HIV/AIDS | ||

| Female | 11 | 39.3 | ≤5 years | 10 | 35.7 |

| 6-10 years | 6 | 21.4 | |||

| >10 years | 12 | 42.9 | |||

Study procedures

Interviews were conducted face to face in a private room at the participating study site (n=21) or by telephone when participants lived in other areas of the country (n=7). An interview guide was developed based on available literature (See Appendix 2) to understand the role of online social network technologies in the HIV continuum of care. This interview guide focused on how people living with HIV/AIDS used online social networks, including their overall use and impression of these technologies, reasons, and barriers to using these technologies, and additional recommendations that would improve the experience of communicating with peers online. It was primarily assessed by two expert reviewers and pre-tested with three members of the target population before the implementation. These early (pilot) interviews were then included in the study as they were reasonably comparable to the subsequent interviews in terms of content and the questions that were asked.

The interviews followed a semi-structured design. However, the order of questions and answers could vary according to the responses of the participants. Follow-up questions were asked and the clarification of points that arose was also sought. Interviews were conducted in the Farsi language, audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Interviews ranged from 25 to 84 minutes (Mean = 55 minutes). One of the interviews conducted by a telephone call was extremely short (14 minutes) and was subsequently excluded from the final analysis due to lack of quality and poor productivity.

Data analysis

Braun and Clarke's (2006) framework for thematic analysis was used in data analysis, in which codes and themes were derived inductively from the interview transcripts and notes. Manual data analysis with the aid of MAXQDA 12 had been started after the first three interviews and conducted concurrently with data collection. Initial codes were generated by labelling data extracts with a code reflecting the meaning of the extract. These codes were then collated into potential themes. This coding was followed by an iterative process, in which the themes were reviewed with the coded extracts and the entire dataset. This review was conducted to ensure the consistent application of codes and themes, and clear de?nitions and names for each theme.

Ethical considerations

A detailed explanation of the research process was provided in the informed consent form (See Appendix 2) where the objectives and the activities involved in the study were discussed. The investigator's contact details were provided and participants' confidentiality was assured. The aim of the study and inclusion criteria were explained and informed consent was sought before the implementation. No names or individual identifiers were used in any reports or publications resulting from this study. The Research Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences has approved the project following the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration and the national ethical guideline for medical research.

Results

Thematic analysis identified four major themes from the qualitative data. These included 1) overall use and impression of online social network technologies, 2) motivations and reasons for adopting online social network technologies 3) barriers to using online social networking technologies, and 4) recommendations.

Theme 1: overall use and impression of online social network technologies

Many participants reported widespread use of online social network technologies. The average person living with HIV/AIDS appeared 3.5-5.7 hours per day online. There are a variety of online social network technologies available and people living with HIV/AIDS had tried some of these tools either for professional or personal purposes. According to the 28 people living with HIV/AIDS who were interviewed in the study, Telegram (83%) and WhatsApp (21%) were the most reported online social network platforms that attracted them. Two participants also reported widespread use of Facebook for communication with physicians and peers from other countries.

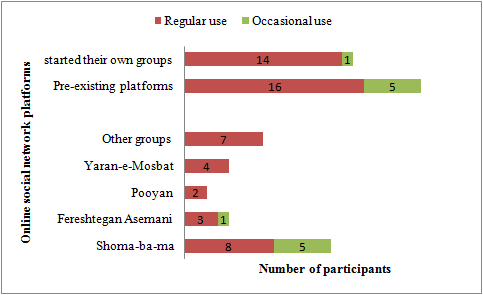

Many people living with HIV/AIDS who participated in the study had frequently used pre-existing platforms (groups) established by health care providers or community-based organisations. Some participants had also reported starting their own groups for communicating with peers. Figure 1 shows an overview of the platforms used by participants of the study. As shown in Fig.1, 15 participants mentioned using pre-existing platforms regularly and four participants used them occasionally. The participants preferred using pre-existing platforms such as Shoma-ba-ma (a group administered by a collaboration of the Ministry of health and community health care providers) because of its popularity among people living with HIV/AIDS across the country.

Many participants indicated that they would prefer online platforms for communicating, sharing, and making friends virtually. Posting for a group to read and respond to and communicating between users and health staff/ professionals were the next mentioned forms of social networking activities. One-to-one messaging was less likely reported among participants. Required disclosure of identity was not reported by any people living with HIV/AIDS while social networking. In the six months prior, over two-thirds of respondents have shared their personal experiences about continuum care, alternative treatments, and drug adverse events in-person or as group discussions. The rest preferred just reading other members' messages. In general, all participants agreed that online social networks were useful and helped them in coping with the disease more efficiently. Some participants felt that communicating with peers through online social networks has made them strongly motivated and impressed. Almost half of the participants were satisfied with using these technologies and have recently invited their friends to these platforms as members.

Drivers and reasons for adopting online social network technologies

Seeking health information and medical advice was reported as one of the primary reasons for people living with HIV/AIDS to join online social network platforms. The participants stated that online social networking platforms provided users with access to reliable health information 24/7. The use of online social networking platforms in emergencies where it was not possible to visit a doctor or health centre, was also reported by some people living with HIV/AIDS in this study. Access to information about self-care, new treatments, drug adverse effects, complementary therapies, and unusual manifestations of the disease were the most frequent topics discussed in the groups. Geographical reach was also identified as a notable benefit by some respondents. Online social networking platforms have provided opportunities to disseminate health information and personal experiences to distant members.

During this period, I think [that] it has helped a lot to those [who are] not able to visit counselling centers or could not remember their questions at the visit time. Since, there are some medical staff and physicians in the group; we can ask our questions on 7/24. This could particularly help members from other cities to access health professionals and physicians online. [Woman, 45 years old]

I used to be in some patient groups but didn't know much about HIV but now I'm in this group, it is much better. I have learned many new things about HIV including nutrition, drug side effects, herbal drugs, and treatment regimens...[I] asked all my questions or read other members' questions about HIV...this has increased my knowledge extensively. [Man, 25 years old]

Participants' responses strongly indicated that online social networking platforms enabled them to stay easily connected with friends and peer groups. Twenty-seven of the participants found it easier to communicate with their close friends through online social network groups and become aware of their routine life, work, feelings, and emotions, and arrange off-line activities. In addition, they could refer to their friends and peers for immediate questions, feedback, and assistance.

It was often reported that online social networking platforms could overcome physical boundaries and facilitate communication with physicians and care providers. A variety of health professionals have participated in online social network platforms to communicate with people living with HIV/AIDS including general practitioners, midwives, clinical psychologists, infectious disease doctors, and social workers. According to the respondents' perspectives, online social networking platforms have changed patient-physician relationships and provided the people living with HIV/AIDS with the advantage of reduced unnecessary use of healthcare facilities and consequently the cost of healthcare services. These platforms could particularly benefit a wide range of people living with HIV/AIDS including those who failed to access mobile phones or the Internet. Some of the participants reported that they disseminated novel information and new knowledge they acquired from health professionals to their offline friends and in-deed people living with HIV/AIDS

We have been friends for 5 years...Here we met each other in the group for the first time and became very close friends since that time... We are very interdependent and always talk about our smallest to our biggest problems here in the group. [Woman, 35 years old]

Many [homeless] kids in Ahwaz rely on me to ask me their questions...I share their questions with doctors in the group and then send the doctor's advice to my friends reciprocal. [Man, 41 years old]

Another reason that participants used online social networking platforms was associated with the opportunities to facilitate social support exchange. Social support refers to the perception that one is cared for, valued, and has assistance available from family, friends, neighbours, co-workers, and members of supportive social networks. These supports can be emotional, informational, or instrumental. Emotional support was frequently reported by many participants as the primary reason for using online social networking platforms. These participants perceived online social network platforms as sources of empathy, concern, affection, acceptance, trust, encouragement, and caring. Many respondents believed that these platforms can let them know that they are valued and accepted. Informational support was also reported as another reason for using online social networking platforms. People living with HIV/AIDS often began searching for information about HIV/AIDS by consulting other patients with similar HIV experiences. Respondents believed that online interactions with peers and sharing lived experiences were effective strategies for learning how to cope with social, physical, and health consequences of the disease. Almost all respondents frequently mentioned this feature during the interviews. It was occasionally reported that online social networking platforms had provided some sort of instrumental supports for people living with HIV/AIDS. Respondents reported some examples of assisting other members or online friends through networking and group announcements.

Sometimes you need someone thinking about you or you need feel valuable when you post to a group and then some users like or comment on your post, this simply makes you feel better. When you are in a bad mood or feel depressed, there is someone to talk with you, this makes you feel you are not alone at all. Talking about your disease in a group of peers makes you feel self-confident and powerful. [Man, 40 years old].

During online interactions among patients, one learns how to express his HIV status instead of hiding it...by presenting ourselves to a group of people without any discrimination or stigma, we are motivated to talk about HIV even among our family or other people. [Man, 38 years old].

In the Kermanshah earthquake, our friends needed help, we collected a lot of help from the group members and send them...Someone in Kermanshah wanted to commit suicide. We went to Kermanshah and tried to convince him...now she is an artist and works in the positive club voluntary. [Man, 35 years old].

Theme 3: barriers to the use of online social network technologies

Despite the great advantages that online social networking platforms bring to people living with HIV/AIDS, sharing irrelevant or disappointing posts was reported as a major barrier to effective engagement in these technologies. Gender issues, conflicts between men and women, and disturbing behaviour were also reported by all women as a major disadvantage of online groups. Some female respondents left the groups and were likely to connect with other females as their initial friends and form single-gender groups. Since women are less likely to be able to negotiate with men about sexual issues, they prefer to join single-gender groups instead. In addition, fear of sexual abuse prevents most HIV-positive women from joining online communities and peer groups.

In the group, you see some members don't say the right words, for example. They do not speak the right words and send irrelevant pictures, poems or notes. [Man, 25 years old].

Some ask unrelated questions [Woman, 38 years old].

Poor engagement of users was also reported by some respondents as one of the main barriers to sharing experiential knowledge. This may be due to a lack of confidence and self-esteem that prevents one from sharing personal ideas and information. According to people living with HIV/AIDS, comments, poor Internet connection, low literacy, and cost were the most notable technical barriers to using online social networking apps.

Unfortunately, many users do not participate in group discussions. There are many physicians and psychologists in the group, but only a few of them react to the patients' questions and concerns. [Man, 44 years old].

We have so many doctors there, only Dr... will answer. [Man, 38 years old].

Many still couldn't believe themselves to ask their questions in the group... perhaps because of low self-confidence. [Woman, 38 years old].

Some respondents described a desire for their providers and group administrators to establish a set of rules and norms in a way that the group members could then understand their responsibilities and authorities. This could prevent the privacy issues, ethical challenges and misconducts reported frequently by respondents. There was often concern that joining new peer groups may lead to privacy and confidentiality issues, particularly for people living with HIV/AIDS who experience social stigma and discrimination in their daily life.

Unfortunately, many users do not participate in group discussions. There are many physicians and psychologists in the group, but only a few of them react to the patients' questions and concerns. [Man, 44 years old].

I'm a member of the group for years. A few days ago, a stranger came into my private and wanted to know whether I was positive or not? I only use one telegram account...this made me a little worried as I have not disclosed my HIV status to anybody even to my family ...this is a negative point that prevents me from engaging in other groups. [Man, 57 years old].

Filtering is a big challenge...if they [government] filter the telegram, nobody can access the group. [Man, 44 years old].

Theme 4: recommendations

Some respondents described a desire for their providers and group administrators to establish a set of rules and norms in a way that the group members could then understand their responsibilities and authorities. This could prevent the privacy issues, ethical challenges and misconducts reported frequently by respondents. There was often concern that joining new peer groups may lead to privacy and confidentiality issues, particularly for people living with HIV/AIDS who experience social stigma and discrimination in their daily life.

In my opinion, group administrators have to establish some rules for group members and justify the kids before adding them to the group...they should prevent posting irrelevant information like jokes, poems, chats, etc to the group so that members could discuss the disease instead. [Man, 33 years old].

Maybe you could start a bot on telegram, classify frequently asked questions, and put the relevant information and advice there. In this way, patients who have an urgent need to information can use the bot to access needed information very fast. [Woman, 45 years old].

Many participants also wanted to expand the online social networking platforms and services provided across these platforms to a broader level of audiences including the general population and HIV at-risk groups. According to study participants, online social networking platforms may also have the advantage of disseminating health information to key populations that are particularly vulnerable to HIV and frequently lack effective access to healthcare services.

You should establish groups or channels that are for youth and teenagers...I am ready to record my voice and send it to the group anonymously to inform the members about the risk of HIV and convince them to take an HIV test here in the positive club[Woman, 46 years old].

You should establish a similar group for sex workers and try to attract them...I don't know how you could motivate them but you may attract them to social networks by incentives... for example give them a present if they could introduce their friends to join the group...in this way you could reach their social network and give them information about the disease[Man, 40 years old].

Discussion

This study has been one of the first efforts to investigate online social networks' use and reasons to participate in online social networking activities among Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS. It has demonstrated that a range of individual, technical and socio-cultural factors influenced Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS regarding online HIV communication and online social networks' use. According to our findings, peer- groups and pre-existing groups established by care providers and community-based organisations were types of online social networking platforms used by respondents. People living with HIV/AIDS were using these platforms for either seeking or sharing health information, staying connected with peers and care providers, and social support exchange. However, cross-posting of users, gender inequality and ethical issues, poor engagement of users, and lack of privacy and confidentiality are major barriers to people living with HIV/AIDS engagement in online social networking platforms.

Qualitative interviews revealed that using mobile Internet and online social networking has been well embraced by Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS. The results showed that almost all participants used mobile Internet and online social networking platforms through their mobile phones. All participants had social media accounts and used online social networking platforms at least daily. The average spent time online through online social networking platforms was 3.5 -5.7 hours daily. These findings are higher than those observed among Chinese and American samples of people living with HIV/AIDS that about 56.5% and 76% of participants used an online social networking site or feature at least once a week respectively (Barman-Adhikari et al., ,2016; Zhang et al., 2018). The higher levels of online social networking platform use among Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS also reflected that the participants had fully leveraged the advantage, convenience, and variable resources provided by these technologies. However, there are some possible explanations for the higher rates of use reported by Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS in this study. Firstly, HIV, sex, and sexuality continue to remain a social taboo in Iran and other countries. Due to religious and cultural norms, Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS experience higher levels of stigma and discrimination in the communities where they live. Since prostitution, sex work, and illicit drug abuse are strictly prohibited in the country, vulnerable populations such as female sex workers and people who inject drugs do not have access to reliable health information and quality health care services. Therefore, Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS are bound to rely heavily on the Internet and online resources for their information acquisition and support. Secondly, as noted above, the results are extracted from semi-structured interviews with a small sample of people living with HIV/AIDS currently using online social network technologies that leave a potential for selection bias which may have skewed the responses in favour of users. Thirdly, both comparative studies were carried out in 2011-13, and usage of online social network technologies was likely less common at that time.

The findings also revealed no significant gender differences in patterns of online social networks' use among people living with HIV/AIDS who participated in the study. Although the results support previous findings that suggested no difference among men and women in using the Internet and online social networking apps among people living with HIV/AIDS (Barman-Adhikari et al.,2016; Coursaris and Liu, 2009; Kalichman et al., 2002), some other studies indicated existing remarkable gender gaps in using mobile technologies, Internet, and online social networks in people living with HIV/AIDS (Goswami and Dutta, 2015; LeFevre et al., 2020). In China, compared to the male group, female people living with HIV/AIDS reflected higher levels of using computers, access to online social network accounts, accessing the Internet via a mobile phone, and longer average time spent online (zhang et al., 2018). It seems that existing differences in online social network users are likely associated with a range of socio-economic factors including affordability, literacy, and digital skills. Perceived lack of relevance, safety, and security issues were also reported to be associated with using mobile Internet and online social network technologies(LeFevre et al., 2020).

As highlighted in the qualitative interviews, seeking/sharing health information online emerged as the main driver for using online social network technologies among Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS. This finding supports other research where it is considered that people living with HIV/AIDS spent more time online using educational and informational features of online social networking apps(Chung, 2014) for seeking (Brown et al., 2017), and disseminating HIV information (Cao et al., 2017). However, disparities in the use of the Internet and online social network technologies for finding health information exist. Increased online social network technologies used for obtaining HIV-related information online has been reported in youth (Navarra et al., 2017), people living with HIV/AIDS with lower antiretroviral treatment adherence (Horvath et al., 2012), and people with low health literacy (Bickmore et al.,2016), indicating insufficient ability to acquire and act on information related to HIV management. Online social network technologies have shown improving access to health information among people living with HIV/AIDS. However, for online social network interventions to be effective, they need to be developed and optimised with people living with HIV/AIDS needs and expectations.

Moreover, online social network apps appear to be an easier method for communicating with peers and health care providers. This is evidenced by 65.5% of the respondents, acknowledging that online social network technologies had an advantage of making it possible for the interviewees to communicate with their old friends, make connections with new friends and stay connected with doctors and healthcare providers. It is thought that in online communities, social relationships are easier to maintain than it is in real life, this is because it is easier to leave a message to an online friend compared to a friend you meet in real life. Online social networking sites are increasingly referred to as ways of keeping in touch with older friends, forming communications with new friends, and maintaining contact with existing friends and peers (Eid and Hughes, 2011; Veinot, 2010). These findings also represented online social network technologies as a viable option to interact with physicians and care providers. The widespread use of online social network technologies among both physicians and patients has proven to cast a positive impact on the quality of patient-doctor interactions. By increasing their knowledge, patients become motivated to actively communicate with their doctors during their medical consultations. Additionally, online social network technologies can empower patients to follow doctors' recommendations, adhere to proposed treatment plans, and discuss their questions and concerns, especially within an online support group. However, available evidence fails to indicate the positive perception of physicians and medical students regarding patient-doctor interactions through online social network technologies including Facebook particularly due to lack of privacy and confidentiality issues (Bosslet et al., 2011; Jain, 2009; Moubarak et al., 2011). Further research should investigate how Iranian physicians and care providers feel about patient interactions within online social network technologies and their motivations behind these interactions.

Participants generally believed that online social network technologies were effective at augmenting social support exchange by illustrating that informational and emotional supports were exchanged most frequently among people living with HIV/AIDS. This could be partly due to the promising role of online social network apps in addressing a range of people living with HIV/AIDS's individual needs including the need for cognition (information gathering), need to belong (gaining social approval, expressing opinions, and influencing others), and collective self-esteem (Eid and Hughes, 2011). These findings support other research where it is demonstrated that online social networks' use brings the advantage of supporting members by providing informational and emotional coping strategies about their health concerns (Chung, 2014). The role of social support on both the physical and psychological well-being of people living with HIV/AIDS has been extensively documented (Khamarko et al., 2013; Qiao et al., 2014; Toth et al., 2018) and online support groups have been demonstrated to have a positive effect on disclosure, mental well-being and engagement with HIV care (Barman-Adhikari st al., 2016; Hightow-Weidman et al., 2018; LeGrand et al., 2018). Social support has also been associated with less depression (Matsumoto et al., 2017; Vyavaharkar et al., 2011), positive health behaviour, improved antiretroviral treatment adherence (Geroge and McGrath, 2019; Mao et al., 2019), coping, and quality of life (Charkhian et al., 2014; Santos et al., 2018), through its functional components including informational, emotional, and instrumental support.

Despite the widespread use of online social network technologies among Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS, there are several distinct barriers to people living with HIV/AIDS engagement in online social network platforms. Cross-posting of users, privacy issues, and gender issues were frequently reported by people living with HIV/AIDS who participated in the study as disadvantages and barriers to using online social network technologies. It seemed that people living with HIV/AIDS did not feel secure when engaging in HIV-related communications or releasing their HIV status in online social network platforms and virtual groups. Additionally, limited confidence and self-esteem could be a reason that held people back from engaging in HIV communication activities. According to our findings, some respondents preferred to start their virtual groups rather than using pre-existing groups. This was partly due to strict group rules designed to control disturbing behaviour and reduce conflicts among group members. For example, expressing negative emotions such as fear, anxiety, anger, or sadness in group discussions is not recommended and most people living with HIV/AIDS tend to relieve their negative emotions by chatting with a close friend or a peer patient privately. It seems that establishing group norms and values, and making a supportive and friendly environment may hinder the negative consequences and disadvantages of online social network technologies of people living with HIV/AIDS.

Existing social, cultural, and religious frameworks in Iran and other developing countries do not provide a safe environment to access reliable health information about HIV/AIDS without fear and stigma for people living with HIV/AIDS and other marginalised populations such as female sex workers, people who inject drugs, and men who have sex with men. In this context, Internet resources and online social networking platforms bring the advantage of access to health information resources and support by breaking existing social and cultural barriers. While the impacts of using the Internet, and online social networking platforms on HIV knowledge (Young and rice, 2011), risk perception (Rice et al., 2010; Young and Rice, 2011), and empowerment (Mo et al., 2014) of people living with HIV/AIDS in developed countries appear to be well-documented, the evidence addressing the needs of HIV vulnerable populations in communities with conservative cultural norms regarding sexual habits are limited. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that designing interventions based on these technologies requires a multifaceted approach with particular attention to social and cultural norms. To devise online social network technologies for HIV education and prevention in countries like Iran and other developing countries, it is important to study the social dynamic and practices of affected populations. Therefore, future studies are needed to investigate the feasibility and acceptability of these interventions among hard-to-reach subgroups such as female sex workers and people who inject drugs in these communities.

The findings of this study should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, the findings are derived from data collected by a non-probability sampling of people living with HIV/AIDS from two government-sponsored health clinics in the Tehran metropolitan area in Iran. As such, these findings are likely not generalisable to a broader population of Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS. These findings are also likely biased by some degree of self-selection, where those who are willing to engage with health facilities and community centres regarding HIV prevention and risk reduction, indicating higher levels of health literacy and perceived susceptibility and severity, may have been more likely to participate in the study. According to the Health Belief Model ((Rosenstock, 1974), individuals with higher levels of perceived susceptibility or severity are more likely to engage in health-related behaviour to prevent the health problem or disease from occurring or reduce its consequences. This model was developed by social scientists to understand the health-related behaviour of people in adapting prevention strategies or screening tests for early detection of diseases.

Conclusion

This study is one of the first efforts to investigate the use and potential of online social networking platforms among Iranian people living with HIV/AIDS. The high rates of online social networking platforms' use among respondents suggest the feasibility and acceptability of implementing online social network-based interventions among people living with HIV/AIDS. The findings also suggest that there is abundant room for the establishment and improvement of online social network-based efforts to address gender issues, confidentiality, and anonymity. Given the considerable prevalence of HIV/AIDS among female sex workers and injecting drug users and other high-risk groups, further efforts should involve all stakeholders and vulnerable populations that target in-demand information and social support services among these sub-groups. Moreover, studies examining the feasibility and acceptability of online-social network-based interventions are needed to help understand the full picture of using these technologies among key populations including sex workers and injection drug users, and tailor the prevention and care interventions accordingly.

Acknowledgements

This study was part of a Ph.D. dissertation supported by the Iran University of Medical Sciences (grant No: IR.IUMS.REC 1396.9421623002). The authors would like to thank the HIV/AIDS Office, the Iranian Ministry of Health for technical support. We acknowledge Dr.AfsarKazerouni, Nazanin Heidari, Elham Rezaiee, Dr. Zahra BayatJozani, and Nasrin Kordi for conducting the initial correspondences and contacts with patients. We acknowledge participants for thetime and insights they offered during the study.

About the authors

Sirous Panahi is an Associate Professor in the Department of Medical Library and Information Science, Iran University of Medical Sciences,Tehran, Iran. He can be contacted at panahi.s@iums.ac.ir.

Azam Bazrafshani is a PhD candidate at Iran University of Medical Sciences. She can be contacted at bazrafshani.a@iums.ir.

Hamid Sharifi is a professor at Kerman University of Medical Sciences. He can be contacted at sharifihami@gmail.com.

Effat Merghati-Khoei is a professor at Tehran University of Medical Sciences. She can be contacted at effat_mer@yahoo.com.

References

- Barman-Adhikari, A., Rice, E., Bender, K., Lengnick-Hall, R., Yoshioka-Maxwell, A., & Rhoades, H. (2016). Social networking technology use and engagement in HIV-related risk and protective behaviors among homeless youth. Journal of Health Communication, 21(7), 809-817

- Bickmore, T.W., Utami, D., Matsuyama, R., & Paasche-Orlow, M.K. (2016). Improving access to online health information with conversational agents: a randomized controlled experiment. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(1), ei. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5239

- Bosslet, G.T., Torke, A.M., Hickman, S.E., Terry, C.L., & Helft, P.R. (2011). The patient-doctor relationship and online social networks: results of a national survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(10), 1168-1174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1761-2

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, S-E., Krishnan, A., Ranjit, Y., Marcus, R., & Altice, F.C. (2017). Assessing feasibility and acceptability of mHealth among underserved HIV+ cocaine users and their healthcare providers. In: Timothy Hale (ed.). Proceedings of Connected Health Conference 2017, Boston, October 25-27, 2017. iProceedings, 3(1), e48. https://doi.org/10.2196/iproc.8676

- Cao, B., Gupta, S., Wang, J., Hightow-Weidman, L.B., Muessig, K.E., Tang, W., Pan, S., Pendse, R., & Tucker, J.D. (2017). Social media interventions to promote HIV testing, linkage, adherence, and retention: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(11), e394. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7997

- Charkhian, A., Fekrazad, H., Sajadi, H., Rahgozar, M., Abdolbaghi, M.H., & Maddahi, S. (2014). Relationship between health-related quality of life and social support in HIV-infected people in Tehran, Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 43(1), 100. https://ijph.tums.ac.ir/index.php/ijph/article/view/4253/3906 (Internet Archive)

- Chavoshi, A., & Hamidi, H. (2019). Social, individual, technological and pedagogical factors influencing mobile learning acceptance in higher education: a case from Iran. Telematics and Informatics, 38, 133-165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.09.007

- Chung, J. E. (2014). Social networking in online support groups for health: How online social networking benefits for patients. Journal of Health Communication, 19(6), 639-659. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.757396

- Coursaris, C. K., & Liu, M. (2009). An analysis of social support exchanges in online HIV/AIDS self-help groups. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(4), 911-918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.03.006

- Courtenay-Quirk, C., Horvath, K.J., Ding, H., Fisher, H., McFarlane, M., Kachur, R., O'Leary, A., Rosser, B.S., & Harwood, E. (2010). Perceptions of HIV-related websites among persons recently diagnosed with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 24(2), 105-115. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2009.0228

- Dulli, L., Ridgeway, K., Packer, C., Plourde, K. F., Mumuni, T., Idaboh, T., Olumide, A., Ojengbede, O., & McCarraher, D.R. (2018). An online support group intervention for adolescents living with HIV in Nigeria: a pre-post test study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 4(4), e12397. https://doi.org/10.2196/12397

- Eid, R., & Hughes, E. (2011). Drivers and barriers to online social networks' usage: the case of Facebook. International Journal of Online Marketing, 1(1), 63-79. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijom.2011010105

- Farhoudi, B., Ghalekhani, N., Afsar Kazerooni, P., Namdari Tabar, H., Tayeri, K., Gouya, M.M., SeyedAlinaghi, S., Haghdoost, A.A., Mirzazadeh, A., & Sharifi, H. (2022). Cascade of care in people living with HIV in Iran in 2019; how far to reach UNAIDS/WHO targets. AIDS care, 34(5), 590-596. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2021.1944603

- Garett, R., Smith, J., & Young, S D. (2016). A review of social media technologies across the global HIV care continuum. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 56-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.10.024

- George, S., & McGrath, N. (2019). Social support, disclosure and stigma and the association with non-adherence in the six months after antiretroviral therapy initiation among a cohort of HIV-positive adults in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care, 31(7), 875-884. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2018.1549720

- Gold, J., Pedrana, A.E., Sacks-Davis, R., Hellard, M.E., Chang, S., Howard, S., & Stoove, M.A. (2011). A systematic examination of the use of Online social networking sites for sexual health promotion. BMC Public Health, 11(583), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-583

- Goswami, A., & Dutta, S. (2015). Gender differences in technology usage—a literature review. Open Journal of Business and Management, 4(1), 51-59. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2016.41006

- Grosberg, D., Grinvald, H., Reuveni, H., & Magnezi, R. (2016). Frequent surfing on social health networks is associated with increased knowledge and patient health activation. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(8), e212. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5832

- Hailey, J. H., & Arscott, J.M. (2013). Using technology to effectively engage adolescents and young adults into care: STAR TRACK Adherence Program. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 24(6), 582-586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2013.03.001

- Hightow-Weidman, L., Muessig, K., Knudtson, K., Srivatsa, M., Lawrence, E., LeGrand, S., Hotten, A., & Hosek, S. (2018). A gamified smartphone app to support engagement in care and medication adherence for HIV-positive young men who have sex with men (AllyQuest): development and pilot study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 4(2), e34. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.8923

- Horvath, K.J., Courtenay-Quirk, C., Harwood, E., Fisher, H., Kachur, R., McFarlane, M., O'Leary, A., & Rosser, B.S. (2009). Using the Internet to provide care for persons living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 23(12), 1033-1041. http://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2009.0163

- Horvath, K.J., Danilenko, G.P., Williams, M.L., Simoni, J., Amico, K.R., Oakes, J.M., & Rosser, B.S. (2012). Technology use and reasons to participate in social networking health websites among people living with HIV in the US. AIDS and Behavior, 16(4), 900-910. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0164-7

- Jain, S.H. (2009). Practicing medicine in the age of Facebook. New England Journal of Medicine, 361(7), 649-651. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp0901277

- Kalichman, S.C.H., Weinhardt, L., Benotsch, E., DiFonzo, K., Luke, W., & Austin, J. (2002). Internet access and internet use for health information among people living with HIV-AIDS. Patient Education and Counseling, 46(2), 109-116. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00134-3

- Khamarko, K., Myers, J. J., & World Health Organization. (2013). The influence of social support on the lives of HIV-infected individuals in low-and middle-income countries. World Health Organization.

- Koufopoulos, J.T., Conner, M.T., Gardner, P.H., & Kellar, I. (2016). A web-based and mobile health social support intervention to promote adherence to inhaled asthma medications: randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(6), e122. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4963

- Kremer, H., & Kironson, G. (2007). People living with HIV: sources of information on antiretroviral treatment and preferences for involvement in treatment decision-making. European Journal of Medical Research, 12(1), 34

- L'Engle, K.L., Green, K., Succop, S.M., Laar, A., & Wambugu, S. (2015). Scaled-Up mobile phone intervention for HIV care and treatment: protocol for a facility randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 4(1), e11. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.3659

- LeFevre, A.E., Shah, N., Bashingwa, J.J.H., George, A.S., & Mohan, D. (2020). Does women's mobile phone ownership matter for health? Evidence from 15 countries. BMJ global health, 5(5), e002524. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002524.

- LeGrand, S., Muessig, K.E., Platt, A., Soni, K., Egger, J.R., Nwoko, N., & Hightow-Weidman, L.B. (2018). Epic allies, a gamified mobile phone app to improve engagement in care, antiretroviral uptake, and adherence among young men who have sex with men and young transgender women who have sex with men: Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 7(4), e94. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.8811.

- Li, Y., Polk, J., & Plankey, M. (2013). Online health-searching behavior among HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative men who have sex with men in the Baltimore and Washington, DC area. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(5), e78

- Lwoga, E. T., Nagu, T., & Sife, A. S. (2017). Online information seeking behaviour among people living with HIV in selected public hospitals of Tanzania. Journal of Systems and Information Technology, 19(1/2), 94-115. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2479.

- Mao, Y., Qiao, S., Li, X., Zhao, Q., Zhou, Y., & Shen, Z. (2019). Depression, social support, and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV in Guangxi, China: a longitudinal study. AIDS Education and Prevention, 31(1), 38-50. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2019.31.1.38.

- Marent, B., Henwood, F., Darking, M., & Consortium, E. (2018). Development of an mHealth platform for HIV care: gathering user perspectives through co-design workshops and interviews. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 6(10), e184. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.9856.

- Matsumoto, S., Yamaoka, K., Takahashi, K., Tanuma, J., Mizushima, D., Do, C. D., & Oka, S. (2017). Social support as a key protective factor against depression in HIV-infected patients: report from large HIV clinics in Hanoi, Vietnam. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15768-w

- Mo, P.K., & Coulson, N.S. (2008). Exploring the communication of social support within virtual communities: a content analysis of messages posted to an online HIV/AIDS support group. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11(3), 371-374. http://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0118

- Mo, P.K., & Coulson, N.S. (2014). Are online support groups always beneficial? A qualitative exploration of the empowering and disempowering processes of participation within HIV/AIDS-related online support groups. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(7), 983-993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.11.006

- Mo, P.K., & Coulson, N.S. (2012). Developing a model for online support group use, empowering processes and psychosocial outcomes for individuals living with HIV/AIDS. Psychology and Health, 27(4), 445-459. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.592981

- Moubarak, G., Guiot, A., Benhamou, Y., Benhamou, A., & Hariri, S. (2011). Facebook activity of residents and fellows and its impact on the doctor-patient relationship. Journal of Medical Ethics, 37(2), 101-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jme.2010.036293.

- Muessig, K.E., Bien, C.H., Wei, C., Lo, E.J., Yang, M., Tucker, J.D., Yang, L., Meng, G., & Hightow-Weidman, L.B. (2015). A mixed-methods study on the acceptability of using eHealth for HIV prevention and sexual health care among men who have sex with men in China. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(4), e100. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3370.

- Muessig, K.E., Pike, E.C., LeGrand, S., & Hightow-Weidman, L.B. (2013). Mobile phone applications for the care and prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases: a review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(1), e1 https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2301.

- Qiao, S., Li, X., & Stanton, B. (2014). Social support and HIV-related risk behaviors: a systematic review of the global literature. AIDS and Behavior, 18(2), 419-441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0561-6

- Reeves, P. M. (2001). How individuals coping with HIV/AIDS use the Internet. Health Education Research, 16(6), 709-719. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/16.6.709.

- Rice, E., Monro, W., Barman-Adhikari, A., & Young, S.D. (2010). Internet use, social networking, and HIV/AIDS risk for homeless adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(6), 610-613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.016.

- Rosenstock, I. M. (1974). Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education Monographs, 2(4), 328-335. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019817400200403.

- Samal, L., Saha, S., Chander, G., Korthuis, P.T., Sharma, R.K., Sharp, V., & Beach, M.C. (2011). Internet health information seeking behavior and antiretroviral adherence in persons living with HIV/AIDS.AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 25(7), 445-449. http://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2011.0027.

- Santos, V.da F., Pedrosa, S.C., Aquino, P.de S., Lima, I.C.V.de, Cunha, G. H.da, & Galvao, M.T.G. (2018). Social support of people with HIV/AIDS: The social determinants of health model. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 71(suppl. 1), 625-630. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0346.

- Seyedalinaghi, S., Leila, T.A., Mazaheri-Tehrani, E., Ahsani-Nasab, S., Abedinzadeh, N., McFarland, W., Mohraz, M. & Mirzazadeh, A.(2021). HIV in Iran: onset, responses and future directions. AIDS, 35(4),529. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002757

- Sharifi, H., Mirzazadeh, A., Shokoohi, M., Karamouzian, M., Khajehkazemi, R., Navadeh, S., Fahimfar, N., Danesh, A., Osooli, M., McFarland, W., & Gouya, M.M. (2018). Estimation of HIV incidence and its trend in three key populations in Iran. PloS one, 13(11), e0207681. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207681.

- Shokoohi, M., Karamouzian, M., Khajekazemi, R., Osooli, M., Sharifi, H., Haghdoost, A. A., & Mirzazadeh, A. (2016). Correlates of HIV testing among female sex workers in Iran: findings of a national bio-behavioural surveillance survey. PloS one, 11(1), e0147587. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147587.

- Stonbraker, S., Befus, M., Nadal, L.L., Halpern, M., & Larson, E. (2017). Factors associated with health information seeking, processing, and use among HIV positive adults in the Dominican Republic. AIDS and Behavior, 21(6), 1588-1600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1569-5

- Toth, G., Mburu, G., Tuot, S., Khol, V., Ngin, C., Chhoun, P., & Yi, S. (2018). Social-support needs among adolescents living with HIV in transition from pediatric to adult care in Cambodia: findings from a cross-sectional study. AIDS Research and Therapy, 15(1), Article 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-018-0195-x.

- Veinot, T.C. (2010). 'We have a lot of information to share with each other'. Understanding the value of peer-based health information exchange. Information Research, 15(4), paper 452. http://www.informationr.net/ir/15-4/paper452.html. (Internet Archive)

- Vyavaharkar, M., Moneyham, L., Corwin, S., Tavakoli, A., Saunders, R., & Annang, L. (2011). HIV-disclosure, social support, and depression among HIV-infected African American women living in the rural southeastern United States. AIDS Education and Prevention, 23(1), 78-90. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2011.23.1.78

- Whiteley, L., Brown, L., Lally, M., Heck, N., & van den Berg, J.J. (2018). A mobile gaming intervention to increase adherence to antiretroviral treatment for youth living with HIV: development guided by the information, motivation, and behavioral skills model. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 6(4), e96. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.8155.

- Young, S. D., & Rice, E. (2011). Online social networking technologies, HIV knowledge, and sexual risk and testing behaviors among homeless youth. AIDS and Behavior, 15(2), 253-260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9810-0.

- Zhang, Y., Li, X., Qiao, S., Zhou, Y., & Shen, Z. (2018). Information Communication Technology (ICT) use among PLHIV in China: a promising but underutilized venue for HIV prevention and care. International Journal of Information Management, 38(1), 27-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.09.003.

How to cite this paper

Appendices

Appendix1: Interview guide

Part 1: general information

1. SEX FEMALE? MALE ?

2. How old are you? .... Years I don't know/ do remember? No answer?

3. How much did you study? (The highest grade you passed)

Illiterate? reading & writing? elementary school? high school or Diploma? University?

I don't know/ do remember? No answer?

4. What is the most important source of your income or financial support?

Full-time or permanent employment? Part-time or temporary employment ? Family support ? Governmental and nongovernmental organizations ? No income ? Other .......

I do not know/do remember ? No answer ?

5. How long have you been affected? Duration to month. I do not know / I do remember ? No answer ?

6. How did you get the disease?

Unprotected vaginal or rectal sex (without condom use) ?

Joint use of syringes, needles, or any other means used for the preparation of drugs ?

Tattooing or piercing skin using contaminated equipment ?

From mother with fetal or infant ?Other reason (please explain) .

Do not know/do not remember?

7. Have you ever had a history of substance abuse or addiction or psychotropic druguse in the last month? (Use of this substance without permission or prescription) Yes ? No ?

Do not know/do not remember ? No answe

Part II: Characteristics related to the use of online social networks

1. Do you use any online social networking software such as Telegram, WhatsApp, and Facebook?

2. On average, how many hours per day/week are you present on these social networks?

3. What are your reasons for using online social networks?

4. 4. Do you communicate with patients like you through a telegram or other social networks privately or collectively? (For example, be a member of the group or channel that your friends or other patients are in) How do you feel when you are dealing with patients like you on social networks? Do you feel close and intimate with patients in the group?

5. How useful were your membership in these channels and groups? Can you give me some examples of your experience in this field?

6. How much confidence does membership in HIV channels give you to talk with group members about your illness? Do you think that having regular contact with your patients through social networks gives you the confidence to talk about your illness to non-family members or anyone around you?

7. Do you care about and respond to the recommendations and suggestions that social group members provide about your illness?

8. Can communication with other patients via social networks be able to prepare you for your future health situation?

9. In your opinion, will social networking have implications for patients like you and other high-risk groups?

Appendix 2: Informed Consent form

Hi, My name is Azam Bazrafshan. My colleague and I are from AIDS Office, Iranian Ministry of Health. We interview HIV patients to use the results to improve services provided to this population. We are intended to investigate the benefits of using online social networks such as Facebook, Telegram, WhatsApp, and other similar programs for HIV patients. You are being invited to take part in this research because we feel that your experience as anHIV patient can contribute much to our understanding and knowledge of the benefits of online social networks for patients.

Your participation in this research is entirely voluntary. It is your choice whether to participate or not. If you choose not to participate all the services you receive at this Centre will continue and nothing will change.In this interview, I will not ask your name, nor will I need your address. All your answers will be completely confidential. We only use the total responses for the statistical survey. During this interview, private questions may also be asked and I must emphasize that although your honest cooperation is valuable, you can answer any question you think appropriate. The estimated time of the interview is about 30 minutes and the interview is recorded by tape recorder. A gift will be presented at the end of the interview to thank you for the time you devoted.

You do not have to take part in this research if you do not wish to do so, and choosing to participate will not affect your job or job-related evaluations in any way. You may stop participating in the interview at any time that you wish without your job being affected. I will allow you at the end of the interview to review your remarks, and you can ask to modify or remove portions of those, if you do not agree with my notes or if I did not understand you correctly.

I have read the foregoing information, or it has been read to me. I have had the opportunity to ask questions about it and any questions I have been asked have been answered to my satisfaction. I consent voluntarily to be a participant in this study ..... Signature....