Shadow bodies and information sharing: analysing obstacles in mental health care provision

Jessa Lingel, Megan Bogia, and Chloé Nurik.

Introduction. In the context of mental health, obtaining adequate care requires accurate information sharing across diverse actors, institutions and technologies. Yet, information sharing is often complicated by the vast range of institutional structures involved, creating multiple constraints for both providers and care-seekers.

Method. This study seeks to analyse these obstacles to information sharing through an exploration of provider experiences within a local mental health care system. We conducted sixteen semi-structured interviews with mental health care providers in Philadelphia, USA in order to provide a localized portrait of obstacles to information sharing related to mental health care.

Analysis. Conceptually, we expand on Balka and Star’s (2016) framework of individuals’ shadow bodies to understand how information is shared and fractured within the scope of mental health.

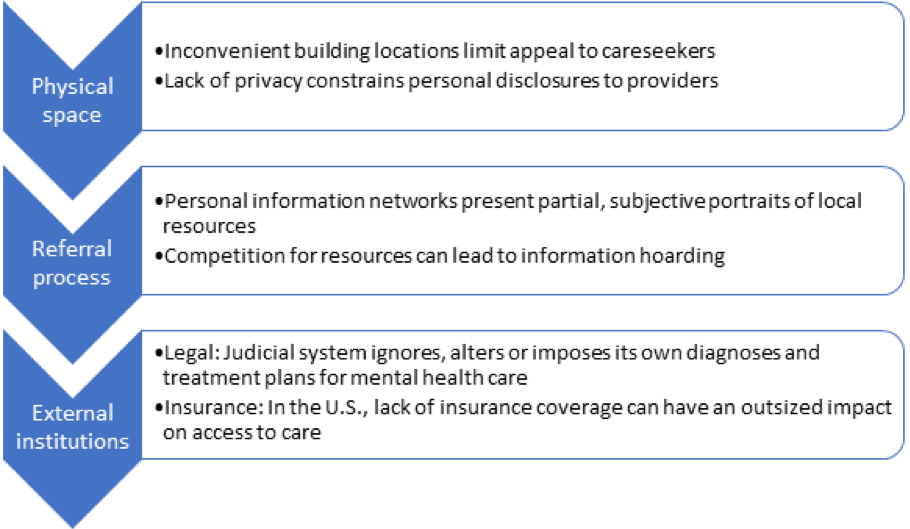

Results. We outline three dimensions of (or obstacles to) information sharing: physical spaces, inter-institutional referrals, and the influence of external institutions. Together, these factors decontextualise and scatter information in a way that complicates the provision and quality of care.

Conclusion. Our paper concludes with a discussion of how our findings can inform information science theory, the design of health data systems and policy related to personal health information.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irpaper879

Introduction

Accuracy and efficiency in gathering, sharing and storing information are uniquely vital to the fields of medicine and psychology (Klenk et al., 2011). The provision of care requires reliable and comprehensive information about a patient’s condition, history and needs. Further, ‘in health care, the provision of care often requires tracking and managing patients across diverse information systems’ (Balka and Star, 2016, p. 420). Consequently, obstacles to information sharing can create barriers to obtaining quality care (Balka et al., 2012; Brailer, 2005). Such difficulties are aggravated in the context of mental health, where the added stigma of seeking care and the increased variety of providers can introduce further complications (Corrigan, 2004; Corrigan et.al., 2014; Saxena et al., 2007).

As in other parts of the health industry, digital technologies have been promoted as essential tools for improving access to and quality of mental health care. Key findings thus far suggest that specialized applications for mental health patients to self-report or track their own symptoms can be just as effective as in-person office visits for diagnosis and treatments (Lederman et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2018; Williams, 2016). Researchers have also noted that digital technologies can provide important forms of social support through message boards and crowdsourced information resources (Bronstein, 2014; Rothschild and Aharony, 2016). Within information science, a key focus has been the shift from paper to digital records in health care systems (Ankem et.al., 2016; Ortega Egea, et.al., 2010). Problematically, patient experiences have often been left out of health-care technology design (Brown, 2008). As a patient representative on a 2014 health care design panel explained, ‘Technologies in hospitals nowadays are at the center of patient care; sadly, at the expense of the patient being at the centre’ (Taneva et al., 2014, p. 1102).

While we share an interest in how providers utilise digital technologies, we situate our work in three key ways. Geographically, we take a highly localised approach, focusing on mental health care in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. As such, our analysis illuminates the specific constraints of an urban environment in the U.S., which involves a particular relationship to external institutions such as the health insurance industry and legal system. A second, topical focus of our analysis is information sharing as specifically related to mental health. Finally, rather than focus on a single condition or technology related to mental health (e.g., personalised health apps or a records management programme), we take a broad view of the sociotechnical landscape at stake in personal health data, considering how a range of technologies and institutional constraints shape information sharing.

We investigate obstacles to information sharing in the context of mental health by drawing on Balka and Star’s (2016) critical interrogation of personal health records. Reflecting on first-hand experiences of navigating the health system, Balka and Star introduced the concept of ‘shadow bodies’ as a way of theorising how medical information fragments over the course of a patient’s care. The authors defined shadow bodies as a constellation of fractured data points that produce an incomplete vision of the patient’s body and needs. Shadow bodies help illuminate the data points that are lost, distorted or hidden as a patient moves from physician to physician, system to system, and institution to institution. While Balka and Star focused on making sense of what happens to a patient’s health data, our approach (1) focuses on obstacles to information sharing from a provider perspective and (2) shifts to the particular context of mental health (and more specifically, mental health in the U.S.).

Regarding terminology, library and information science theory offers a number of terms for theorising information. We use the term information sharing to describe activities related to identifying information in order to solve a problem or complete a task (see Pettigrew, Fidel and Bruce, (2001) for a foundational account of frameworks and paradigms surrounding theories of information). Information sharing is shaped by a range of factors, including professional training and technical skill with information tools (Sapa et.al., 2014). As Baldwin and Rice (1997) have noted, both individual and institutional factors matter in determining how people locate, evaluate and disseminate information. By conducting interviews with individual providers, we attend to both individual and institutional constraints around information sharing. Along with other fields, library and information science has also distinguished between data and information, but we use these terms somewhat interchangeably in this paper.

By analysing the provider counterpart to care-seeker shadow bodies, we can identify crucial obstacles to care, and offer a more robust and holistic understanding of mental health care information sharing. As guiding research questions for this project, we ask what obstacles surface in the process of providing mental health care, and how do these obstacles shape information sharing about a patient’s individual needs? In the next section, we review related work, focusing on barriers to information sharing within health information sharing. We then turn to a discussion of shadow bodies as a key framework for our analysis before describing our methodology. Our findings section outlines key barriers to information sharing as identified by the mental health care providers we interviewed. We conclude with a discussion of implications for theory and policy.

Previous work: information and communication technologies and mental health information sharing

Navigating the mental health care system poses two key challenges for health care providers and care-seekers: (1) the complexity of the system, which includes a wide variety of treatment facilities and operations; and (2) societal stigma, which presents barriers to equitable access to resources and reception of care. With regard to the first obstacle, the U.S. has a complicated mental health care system, which includes both private and public services, the latter of which are delegated to specific county or city authorities. As a result, ‘there are actually multiple mental health care authorities and systems within many states’ (Drake and Latimer, 2012, p. 47). Local municipalities in the U.S. (as elsewhere) are known to have poor organisation and limited funding for mental health care services (Ramsten et al., 2017). This multiplicity is aggravated by intersections with the insurance and legal systems, which can impede access to care and (in the latter case) increase the likelihood for an individual to experience a mental health crisis (Sommers et al., 2017). Compounding these problems, addressing mental health-related issues typically requires both ‘community-based and hospital-based services’ (Bourgeois, et al., 2010, p. 879). Therefore, care-seekers must navigate a complex landscape, spanning physicians, community organisations and (often) online platforms to obtain comprehensive treatment (Becker, 2001; Drake and Latimer, 2012; Ernala et al., 2017; Kakuma et al., 2011). Collaborating across these diverse parties and infrastructures can be extremely challenging (Lederman et al., 2014); As Mechanic (2012) has pointed out, ‘poor continuity and continuation of care and limited adherence on the part of providers to practice standards’ (p. 378) frequently lead to uneven levels of care.

Forms of stigma associated with mental health pose additional barriers to care. Despite the prevalence of mental health-related needs - nearly half of the U.S. population is likely to develop a diagnosable mental health condition over their lifetimes (Schaefer et al., 2017) - many individuals do not seek care. Reluctance to seek care can stem from the cultural tendency to minimise the severity of mental health concerns, and thus the need for treatment (Corrigan et.al., 2014). Additionally, the phenomenon of double stigma can stratify or preclude care for historically marginalised groups, particularly along the lines of gender, religion, age, socioeconomic status, race, sexuality, disability, criminal history, and substance abuse (Gary, 2005, p. 979). For individuals in disadvantaged groups, general social stigma surrounding mental health is compounded by additional factors (e.g., a lack of cultural sensitivity), which can impact the quality of care received (Alvidrez, 1999; Gary, 2005; Paris and Hoge, 2010; Snowden, 2003). Double stigma also presents specific complications for the collection and sharing of information, in that discriminatory beliefs about under-represented groups can play a role in care decisions and record-keeping. In combination, these factors create a labyrinth of institutions, personnel and records. As a result, the struggle for mental health care is not just about meeting a demand for resources, it is also and crucially about flows of information between patients, providers and surrounding institutions.

As we noted earlier, digital technologies have been presented as a potentially crucial tool for addressing barriers to researching and obtaining mental health care. Recent studies have begun to identify a series of system-wide barriers that can complicate information sharing as patients and care teams engage across a platform. Patients and clinicians, for instance, might differ on what data should be communicated (O’Kane and Mentis, 2012), and patients may not be able to interpret results based on the platform’s structure (Solomon et al., 2016). According to Cairns et.al. (2014), data entry may be influenced by the user’s emotional state when engaging with the platform, with higher accuracy levels tied to positive emotional states. Moreover, data are obtained, recorded, and exchanged within a dynamic municipal environment, where ‘regulatory barriers, thresholds, waiting lists and lack of insurance often hamper the accessibility’ of care (Schout et.al., 2011, p. 666). Consequently, it is important to examine such barriers on both individual and institutional levels. Answering this call, a recent study by Gui and Chen (2019) explored individuals’ interactions with the health care system, focusing on patients’ strategies for navigating systemic problems. While this study is a useful start, we argue that further analysis (particularly from the provider perspective) can more precisely define barriers and obstacles in order to improve the design of information and communication technologies, information sharing, and care provision.

Theoretical frameworks: shadow bodies and information sharing

Balka and Star (2016) defined shadow bodies as fragmented visions of the whole patient, or ‘the partial views of bodies, derived from illumination of some aspects of the body which, like a shadow, leave some body parts underemphasised or less visible, and exaggerate others’ (p. 425). In developing shadow bodies as a concept, Balka and Star focused on care-seekers’ journeys through complex and often highly-specialised health care systems. Upon entry into a health system, Balka and Star described how the singular context of each department or office (e.g., the ambulance or the emergency room) alters and impacts the patient’s data. Staff will often record information relevant to a particular context and likewise omit information deemed irrelevant; these highly-contextualised practices limit the total amount of information on patients and make such data less likely to be saved and shared successfully across parties.

Despite growing demands from the federal government and hospital administrators to standardise and digitise patient health data in the U.S., processes of documentation remain unevenly administered and difficult to regulate (Ebeling, 2016). In the absence of consistent data collection, ‘partial representations and abstractions’ of patients are formed through roughly assembled and specialised notes and data (Balka and Star, 2016, p. 425), which undergo constant de- and re-contextualisation. As a result, data are separated and scattered across an individual’s health care experience, creating shadow bodies that claim to represent the whole of the person seeking care but in reality only capture a small, select part of the bigger picture.

We see shadow bodies as a generative but under-used concept; as a way of contributing to the concept’s development and complementing its original focus, we turn to mental health care providers. Taking a highly-localised approach (that is, focusing on providers within a single city), our goal is to conceptualise how providers understand and experience shadow bodies when it comes to matching clients and resources.

Methods

We draw on semi-structured interviews (see Appendix) and focus groups with health care providers to understand the movement of and barriers to the flow of mental health care information. We restricted our recruitment to providers working in Philadelphia, PA in order to examine how information circulates (or does not circulate) on a local level. Philadelphia is home to roughly 1.5 million residents, and is the sixth largest city in the U.S. For the past several years (and in contrast to national trends), Philadelphia has maintained a high poverty rate of 25.3%, making it the poorest of the ten most populous cities in the U.S. (U.S. Census, 2018). Approximately 10% of residents lack health insurance, and within the state of Pennsylvania, there are an estimated 420 clients to a single mental health care provider, compared to approximately 310 to one in top-ranking states (County Health Rankings, 2019). This demographic and economic data helps situate the structural barriers to mental health care in Philadelphia. By design, our interview data are highly localised, but we hope that our analysis may be transferable to conceptualising mental health care resources in other cities, as well as information sharing in other institutional contexts.

Our project was approved by the affiliated university’s Institutional Review Board. Interviews were conducted by graduate students in a qualitative methodology course taught by the first author, with each student - including the second and third authors - conducting an interview (n=16). Interviews were semi-structured to allow for a degree of fluidity while retaining thematic consistency across the interview process (Corbin and Strauss, 2015).

This investigation grew out of a collaborative effort between university researchers and a local activist group, the Creative Resilience Collective, which is committed to facilitating access to mental health care resources for underserved populations in Philadelphia. Participants were recruited through the Collective’s contacts and extended through snowball sampling (Tracy, 2012). Working within the Collective’s contact list, the authors adopted a maximum variability strategy (following Liberati et al., 2019) to capture as many viewpoints and institutional backgrounds as possible. Although our analysis documents the importance of health-related institutions, such as insurance companies and government agencies, we limited recruitment to people who worked directly with clients. This approach reflects the networks of our activist collaborators, who were more familiar with organisations that worked directly with underserved populations in Philadelphia, as opposed to institutional players who were more removed from providing care.

Interviews were conducted from February to May 2018, with sixteen health care providers from a range of institutions, including non-profitorganisations, public services, private practices or behavioural facilities, institutions of higher education, and community meeting groups (see Table 1). As will become clear in our findings, institutional affiliation (e.g., non-profit, private practice) and care context (e.g., focus on a particular population or treatment area) can shape relationships to information sharing in key ways. As such, we list basic demographic information about each participant, as well as his or her affiliations.

| Interviewee | Sex | No. of years as a practitioner | Affiliation and care context |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | M | 8 | LGBTQ non-profit |

| P2 | F | 15 | Community health non-profit |

| P3 | F | NA | Non-profit re-entry programme |

| P4 | M | 18 | Private practice |

| P5 | F | 6 | Non-profit re-entry programme |

| P6 | M | 12 | Telephone counselling |

| P7 | M | 13 | Non-profit housing and mental health programme |

| P8 | M | 33 | LGBTQ-focused non-profit |

| P9 | F | NA | General social work non-profit |

| P10 | F | NA | Incarceration programme |

| P11 | F | 3 | Private practice (Therapy) |

| P12 | F | <1 | Non-profit social work |

| P13 | M | 4 | LGBTQ non-profit |

| P14 | F | 4 | Non-profit addiction treatment foundation |

| P15 | M | 1.5 | Private outpatient rehab centre |

| P16 | F | 18 | Non-profit re-entry programme |

One of the most collaborative processes with the Creative Resilience Collective involved our interview protocol. Given that activist members had extensive experience navigating Philadelphia’s mental health care system, both as clients and practitioners, we sought their expertise in developing interview questions that were grounded in the local context of seeking mental health care resources. Interview themes included inter-institutional communications, operations, and the influence of continued stigmatization of mental health in the region (see appendix for the full protocol). Interviews ranged from thirty minutes to two hours. All interviews were conducted in-person or over the phone and were audio-recorded and self-transcribed. As with any study, our project was limited by certain methodological decisions. We chose to focus on providers in order to develop a portrait of one facet of mental health care, but further research that takes into account both care-seekers’ experiences is certainly needed.

To analyse the interview transcripts, we used open coding (Kakuma et al., 2011) to identify common barriers to mental health care, starting with high-level themes related to our research questions, including obstacles to care, stigma, and information sharing. After the authors coded three interviews separately, the team met to discuss emergent themes within the broader categories and adapt the codes accordingly. This consultation process produced analytical consistency as we coded the remaining interviews. Resulting themes in the first cycle included integration of care, navigating the healthcare system, self-care, human-centred care, Philadelphia, trial and error, and intimacy. In subsequent cycles, additional themes of accountability, family, the legal system, insurance, profit motive, technology, space, scarcity of resources, and sexuality were developed. After consensus was reached on the definitions of the codebook, the three authors divided and coded the remainder of the interviews in NVivo, a qualitative coding program that allows researchers to code, track, store, and organise information across interviews electronically.

As researchers studying a sensitive topic, it is important to acknowledge our own positionality vis-à-vis mental health. While none of the authors are mental health care providers, we have separately sought and received treatment in Philadelphia for mental health. We believe that these experiences have helped us to empathise with providers seeking to provide mental health care and to think critically about processes of information sharing in regard to mental health. Our approach to qualitative research assumes that all investigators bring some degree of bias to the topic of study, and our goal has been to acknowledge our different relationships to mental health while looking for themes and patterns in interview data.

Findings

Like many major cities, Philadelphia’s mental health care system is complex and overburdened. Although participants worked in many different institutions, through discussions with providers, we identified three key themes that consistently disrupted or constrained information sharing: (1) physical space; (2) difficulties surrounding referrals; and (3) interactions with external institutions. These factors shaped flows of mental health information, fracturing care-seeker information into shadow bodies and complicating the provision of adequate care.

Physical space

In interviews, constraints of physical space emerged in two categories: the location of the care institution and the physical characteristics of the care facility. Regarding the first category, and in keeping with prior work (Balka, et.al., 2008; Curtis et al., 2007; Wood et al., 2013), providers we interviewed identified a range of spatial and geographic concerns, including an institution’s proximity to family, distance from negative influencing factors, and accessibility via public transportation. Several participants noted that if a facility is not available in a location that meets the client’s needs, it can hinder a client’s willingness to seek care or exclude altogether the possibility of utilising the institution.

Providers also described how the physical characteristics of the institution can impact a client’s mental health care and likewise generate shadow bodies of data. When clients enter an institution’s building (the literal point of entry into the mental health care system), they are often received by a provider, who must quickly gather information about them. Yet information intake can sometimes be impacted or curtailed by the surrounding space. For instance, buildings with open floor plans lack privacy, making it difficult for providers and clients to have sensitive conversations and limiting care-seekers’ privacy and the ability of the institution to serve as a meaningful refuge (Edwards et al., 2000). As P1 detailed:

When I’m trying to have, like, real intense conversations or real one-on-one[s], to cater to the actual client or participant, it gets bombarded because I have four other people waiting, and people are knocking on the door and [are] like, ‘Are you done, are you done, are you done?’ ... So, things like that, if I was able to have like intensive conversations there, and really intentional ones, then I personally would have felt, like, more at ease.

Echoing research on how library design shapes user experience (Bryant et.al., 2009), physical space impacts information sharing between care-seekers and providers. Before a client’s health information is even entered into a digital system, it can be shaped (and even distorted) by a building’s physical structure and location.

In addition, buildings that are too spacious can hinder necessary collaboration between providers. For example, one provider expressed concerns about the eight-acre property of her organisation. The institution’s paper recordkeeping system required providers to cross the property simply to retrieve a person’s file, which made pulling information about a client arduous and time consuming. P11 explained:

We don’t have electronic medical records, which makes my life a nightmare … So just to get someone’s diagnosis, for example, I have to walk to the complete other side of the building to get it in a file … So there’s a lot of times I need information that I can’t get immediately because there’s no electronic system.

Both limited and excessive physical space has the potential to influence information-sharing practices, underscoring the importance of carefully considering the physical design of mental health care institutions (Paris and Hoge, 2010).

Physical space can disrupt information sharing, creating a limited vision that emphasises desensitised, simplified summaries of the client and leaving out key concerns and experiences. For Balka and Star (2016), patients experience shadow bodies as a confounding process of data disaggregating and aggregating as they move through a health institution. Providers experience similar frustrations of disruptive, unreliable information sharing; and even as these barriers may come to feel predictable, they remain difficult to mitigate.

Barriers of inter-institutional referrals

In interviews, the referral process emerged as a crucial juncture of information sharing. Providers make referrals when they have a client in need of a specific kind of care or set of resources. If a provider initially encounters a client in need of mental health care, but later finds that the client needs additional services (for addiction, for example, or for LGBTQ-support), she must make a referral to another provider or institution. In the context of shadow bodies, referrals represent crucial moments when information sharing is simultaneously deeply important and easily disrupted.

As providers attempt to gather data on local resources, the absence of a standardised system for the exchange of data scatters and fragments information (Kaiser and Karuntzos, 2016). Complicating the issue, mental health care organisations frequently do not have adequate funding, resulting in well-documented issues of understaffing, burnout, and turnover (Paris and Hoge, 2010; Edwards et al., 2000). Inconsistent staffing can further disrupt the referral process. Without reliable information about local resources, providers often rely on a loose network of personal contacts to make referrals. Yet low pay, under-employment, unreliable funding and burnout result in a constant flux of these personal contact networks, creating a sense of uncertainty and contributing to partial or out-of-date records. These inter-institutional obstacles reflect pivotal junctures where a client’s contextualised data drop out or fail to register, often in ways that disrupt or upend care.

Limited funding and minimal external regulation can also lead to guarding rather than sharing information. In a climate of scarcity, hoarding data about available resources was viewed as a way to protect resources. P1 explained the pressures to treat information, funding, and even clients as a resource to be hoarded rather than shared:

You’re all fighting for the same grants, you’re all fighting for the same funds, so I mean, if I have a person in front of me who needs care, I mean, yeah, I can send them to [another local organisation] because they can do more intentional work, but I also [need to keep clients here] you know? That’s how I’m getting my funding. So sometimes there’s organisations that don’t share people or don’t make proper referrals.

Forced to make pragmatic decisions about client well-being as well as institutional survival, providers can contribute to data inaccuracies, even as these inaccuracies make referrals more difficult within the city.

Particularly among non-profits, competition for resources (and by extension, for clients) produces isolated pockets of information. Within this scarcity of data, providers often have limited information about other health institutions. Multiple providers remarked that they rely mainly on remnant information posted on websites and word-of-mouth connections to make referrals. At the same time, providers recognised that these sources were often unreliable and out-of-date. P5 emphasised how such information can evolve in unpredictable ways, stating that, ‘Somebody would say, "Oh I went to that organisation. They said that they no longer had funding." And then […] they went a few days later, and they were fine’. These unreliable portraits of other provider institutions distort and limit the information available to providers when making critical care decisions such as whether a particular institution could adequately aid a client.

The referral process is key to the well-being of clients. But matching clients and resources is made complex by constant fluctuation in staffing and financial security, as well as unreliable information about other institutions. As Balka and Star (2016) noted, the isolated and transitory nature of shadow bodies can complicate a provider’s ability to refer clients to appropriate organisations, emphasising the ‘importance of context in information handovers’ (p. 423), which may be especially impactful for groups with specialised treatment needs (such as LGBTQ or underage patients - see Herek and Garnets, 2007). While conditions of resource scarcity are rarely inscribed on patient records or institutional documents, these key contextual factors are critical for developing a treatment plan for care-seekers. Since these factors fall out of data collection, however, providers are forced to rely on partial records of both care-seekers and institutions, further jeopardising the ability to provide necessary care and clients’ likelihood of receiving it.

External institutions

Inter-institutional communication is a precarious moment for information sharing. Balka and Star (2016) argued that shadow bodies can be generated at junctures where local and national 'off-stage actors…[have] a vested interest in how data are collected' (p. 426). In the context of mental health, shadow bodies are created by the 'multi-jurisdictional needs of varied stakeholders' (p. 424) who collect information based on their own specific needs. Beyond difficulties of information sharing between mental health care institutions, interviewees identified the two primary sources of institutional information obstacles: the legal and insurance systems. Both systems fracture information through a tendency to minimise extant data on clients' unique mental health considerations, coupled with an overemphasis on considerations related to finances and incarceration.

Legal system

Providers frequently identified Philadelphia’s legal system as a problematic force for people dealing with mental health issues. As public social welfare programs have decreased in the U.S., prisons and jails have become key sites of diagnosing and treating mental health issues - tasks for which these institutions are generally ill-suited, under-staffed, and under-resourced. Of the ten U.S. states offering the least access to mental health treatment, six top the list of highest incarceration rates (Provenanzo, 2016). While federal and state prisons are providing increased mental health care treatment, ‘local jail inmates do not have the same access to medication and counselling while incarcerated as federal and state prisoners’ (Heun-Johnson, 2017, p. 33). In Pennsylvania, approximately 25% of prison inmates (which amounts to about 13,000 individuals - a higher incarceration rate than the national average) have been previously diagnosed with one to three serious mental illnesses (Heun-Johnson, 2017). The significant overlap between the criminal justice system and the mental health care system in Pennsylvania necessitates examining how the legal system complicates information sharing in the context of mental health.

In Philadelphia, the provision of mental health care has four key intersection points with the legal system:

- at time of arrest, police can apprehend an individual or take him/her to a psychiatric hospital

- between arrest and sentencing, a diagnosis may be given, and limited care or medication is available depending on the diagnosis

- at sentencing, a judge can stipulate a mental health care treatment such as program enrolment

- after sentencing or detainment, mental health care can overlap with probation requirements and/or mental health care treatment can be provided within correctional institutions.

At each step, conflicting priorities and definitions can produce uneven or contradictory records of care, needs, and treatment, contributing to persistent and impactful shadow bodies.

Given that ‘different disciplinary lenses necessitate collection of different constellations of data’ (Balka and Star, 2016, p. 423), legal professionals gather information with an eye toward its utilization in the criminal justice system. The legal system rarely consults with mental health care professionals regarding diagnosing or treating conditions (e.g., Modlin, et.al., 1976). Consequently, the majority of decisions impacting care are made from the perspective of criminality rather than medical treatment (Teplin, 1984).

Interviewees expressed frustration with the lack of communication between the legal system and mental health professionals. For clients, the result is often fluctuating diagnoses and uneven provision of care. As P12 explained: ‘When you’re coming in and out of the jail system, they’re constantly changing [the] diagnosis and diagnosing you with things and changing [things] - and that’s just a common thing in the jail system’. The point echoes an argument by Balka and Star (2016), who observed that ‘data aren’t simply collected—they are collected because they are going to be used for something’ (p. 426). The Philadelphia legal system collects data and diagnoses individuals as part of moving them through the criminal justice system. This fluid and inconsistent system of diagnosing care-seekers can lead to mistakes in treatment and contributes to uneven or unreliable records of mental health data.

Within the context of shadow bodies, intersections between mental health care and the legal system produce two constraints for information sharing: the narrow collection of data for the purpose of incarceration rather than treatment and the potential for improper diagnoses. As P10 summarised:

I feel like a huge part of the problem is the justice system doesn’t understand how mental health and substance use treatment works. […] They don’t understand how insurance billing works and that it’s a process to get assessed to meet a level of care and then getting approval for that level of care is an entirely different ballgame and nothing’s a guarantee.

The complexity, differing goals, and separate professional commitments of these multiple institutions lead to a cycle of stop-and-start care, partial data, and conflicting records. As a whole, this pattern undermines the interests of every stakeholder operating in the system: of providers attempting to help care-seekers but bound by institutional constraints; of justice department officials constrained by bail and sentencing guidelines; and most importantly, of care-seekers who are unjustly sentenced and inadequately cared for because of the shadow body reports of their condition and concerns.

Insurance coverage

Insurance companies are another source of interference and intervention in mental health information. In the U.S., health insurance is largely tied to employment, which means that an individual’s ability to obtain care is driven largely by income and full-time employment status. People who are unemployed or under-employed are typically eligible for federal programs like Medicare (for people over 65 or those living with disabilities) or Medicaid (for people with low incomes). Yet even these insurance programs come with barriers to receiving adequate care. When a client is covered by Medicare or Medicaid, providers are paid certain fees by the government, which are lower than what a provider would be paid if care-seekers had coverage from private health insurers. Medicaid reimbursement rates tend to be lower than Medicare reimbursement rates, and Pennsylvania has one of the lowest Medicaid-to-Medicare fee ratios in the nation. Consequently, ‘low reimbursement rates are a disincentive for individual physicians to accept patients with Medicaid coverage and mental health problems’ (Heun-Johnson, 2017, p. 16). This dynamic limits providers’ willingness to accept Medicaid care-seekers, often making an individual’s insurance plan the most salient consideration for treatment referral. For those with Medicaid or Medicare, the emphasis on the clients’ coverage contingently de-emphasises their individual needs in favour of their insurance plan.

Multiple providers described the inherent challenges of obtaining care for anyone on Medicare or Medicaid. As a result, providers develop care with an emphasis on the care-seeker’s coverage rather than their condition. Many participants noted that the emphasis on insurance creates a stratified system of care that perpetuates inequity citywide (See Bishop et al., 2014; Steele et.al., 2007). As P4 summarised:

I kind of explain that there’s kind of, for lack of a better word, a class system where providers who can afford to take insurance have much more time, have flexibility to meet the client’s needs, whereas people who don’t have that much flexibility need to be on an insurance, work in an agency or on an insurance panel, have more restrictions with their time and limitations on what they can do and certain other requirements […]. But these are the struggles that they encounter in finding someone that they can afford basically within their insurance situation. I think that the bar is just set so low for poor people in treatment. I just think there are so many things that would never be acceptable if people had more money and Medicaid wasn’t paying for their treatment.

Another provider (P14) stressed that the overemphasis on insurance is even more concerning when one considers that for certain conditions (such as addiction), the window of having a care-seeker consent to treatment may be brief. Consequently, if a provider has to engage in a prolonged search for an institution that takes Medicare or Medicaid, the window may close before any care is identified. Working within these pressing time constraints, a provider may be forced to consider a client’s insurance plan over their specific treatment needs, potentially placing them in an institution that is not a proper fit.

The insurance system pushes providers to prioritise the plans accepted by institutions over the range of services and distinct specialties they offer, flattening and decontextualising the institutions providing care (Pratt et al., 2006). The prioritization of insurance information exemplifies the inherent tension of letting shadow bodies determine care wherein ‘knowledge based off [of] fixed categories’ cannot possibly capture ‘the reality of individual bodies and their living processes’ (Balka and Star, 2016, p. 419-420). The reductive classification of insurance coverage does a disservice to the complexity of individual needs and institutional services, offering yet another example of partial, distorted information about care-seekers.

Discussion

Interviews with mental health care providers in Philadelphia reveal an overburdened, under-resourced set of people and institutions confronting a range of obstacles, including inadequacies of physical space, difficulties communicating across providers, and complexities introduced by external structures such as the legal system and insurance companies (for a synopsis of our findings, see Figure 1 below). Participant accounts echo a warning from Balka and Star (2016), who noted ‘We have to overcome data-sharing and infrastructural challenges and seek means of supporting analyses that allow us to recognise creative recombinations of traces, of indicators we may not even today recognise as data’ (p. 431). Using shadow bodies as a framework, our analysis of mental health care in Philadelphia offers providers’ perspectives of how information drops out and fragments in the process of matching clients with resources.

Figure 1: Mental health care providers identified three key categories of obstacles surrounding information sharing: physical space, referrals to other providers, and external institutions. Each of these factors can lead to partial or distorted records about care-seekers mental health information.

In their conceptual overview, Balka and Star (2016) noted a litany of constraints or fractures that shape the prism of patient data, including vernaculars in transcribing information, types of storage systems, and departmental or institutional contexts. Building on the metaphor of light and shadow, we argue that processes of information sharing can be conceptualised as the separation of light waves passing through a prism. A care-seeker enters with all their data and experiences in a single (embodied) place. Upon contact with the health system, their information is scattered by individual wavelengths, appearing as different colours that bear limited facial resemblance to the former whole. Each layer has clear edges and distinct properties that vary from each other, and when combined they can blend together to reveal new information not previously revealed or represented.

Frequently, however, obstacles to information sharing make it difficult for providers to see a comprehensive image of care-seeker data. These obstacles act like filters that present only one wavelength, while others drop out or appear distorted. Providers may feel forced to concentrate on whether or not a care-seeker has insurance or a criminal record when making decisions about referrals, while constraints on physical space can lead care-seekers to omit key components of their mental health history.

In our conversations with providers, we found that the most commonly identified obstacles or barriers were not necessarily tied to the operations within an institution itself but rather the structures and systems surrounding them, specifically:

- the physical spaces of facilities themselves;

- information sharing between institutions;

- the influence of external institutions with conflicting priorities:

- the legal system;

- the insurance systems.

Together, these factors intersect to create a prism, scattering a care-seeker’s data into partial and sometimes distorted records. The continual and active influence of this prism can impede providers’ abilities to offer holistic and contextualised care. Put another way, the prism can:

- shape what information is gathered about care-seekers and their needs;

- decontextualise information, prioritising one wavelength of information and failing to capture a holistic portrait.

Often, this reshaping and decontextualisation happens before technological interventions favoured by researchers and health professionals, such as health apps or messaging within a department-specific setting, can be introduced.

Note that we are not suggesting that shadow bodies are always produced by the same institutional factors we identified here. Shadow bodies are always context dependent and produced by highly localised obstacles. Rather, our investigation is meant to demonstrate that a grounded, holistic account from providers is crucial in anticipating flows and disruptions of mental health information sharing. By complementing the shadow bodies framework with a metaphor of prisms, we offer a clearer vision of how and where fractures in information sharing occur, and how providers might begin to put these pieces back together and improve the provision of care.

Conclusion: implications for design and policy

In addition to further developing the concept of shadow bodies, our findings have implications for both technological design and health policy. Technologists have developed a number of mental health care tools for improving patient compliance, contact with providers, and forms of social support. Yet such tools require an in-depth accounting of the challenges involved in providing mental health care. We echo the agenda of Balka et al. (2012), who were ‘concerned with identifying both the formal and informal aspects of work, and elements of work which are obvious and visible, as well as those which are tacit and often invisible, and hence left unaccounted for in technology design’ (p. 20). By focusing on the formal and informal aspects of mental health providers’ work, we are able to suggest implications for both technology design and information policy.

Difficulties in capturing medical records are well documented, but the problem of partial, distorted, or missing data is set to become more difficult as the Internet of Things develops further into health care. Despite the popularity of interventions such as apps and self-tracking devices, we are hesitant to assume that more points of data capture (required by the Internet of Things) will meaningfully reduce obstacles of information sharing. Shadow bodies can just as easily be produced from a deluge of data as from a dearth. Indeed, producing more data may only exacerbate confusion (and jeopardise individual privacy).

We also note that providers were all but unanimous in voicing the need for centralised information about local resources. When asked what they would change about the mental health care system in Philadelphia, providers repeatedly expressed the need for a shared information system between institutions, echoing what Balka and Star (2016) referred to as the ‘dream of a common infrastructure’ (p. 421), that could improve inter-institutional communication. In particular, providers frequently requested technology that would provide context about institutional resources, such as one that could give ‘a general overview of what each agency can and can’t do’ (P9) or ‘a database of resources where I could go…if I’m looking for a particular type of treatment’ (P10). Creating a highly localised database with robust systems for both pulling and pushing information - of both publishing up-to-date data about organisations as well as making it accessible for providers’ extraction and use - would greatly assist the referral process. From our conversations with providers, we suggest a focus on building online referral tools that are dynamic and crowd-sourced but subject to expert review.

On the client side, care-seekers need more access to and control over their own records and also, crucially, the ability to add to, contest, or explain their data (principles akin to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation). Marginalised populations in particular - including those who might be impacted by double stigma, who have or are interacting with the justice system, and who have Medicaid, Medicare, or no insurance - should be better able to understand how their data might intersect with other institutions in advance and given space to update these records as desired on a continual basis. Designers should prioritise context and open up data capture for clients to introduce nuance on their own terms. Ideally providers would be able to combine this technology with extended conversations with care-seekers about what types of information exchange are both possible and preferred by the individual to further contextualise data exchanged through the medium.

While technological solutions may mitigate the problem of data sharing among providers (particularly during the referral process), regulatory and policy reforms are needed to address information hoarding, insurance exclusions, and the overreliance on the criminal justice system to provide mental health care. Researchers in health informatics are increasingly calling attention to the failure of major U.S. health policies such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) - which restricts and regulates the sharing of American medical information - to account for complexities of health data (Ebeling, 2016). Sharing data in a timely yet confidential way between a care-seeker’s multiple providers is essential to the provision of care in a highly specialised health care system. More robust policy frameworks are needed, both to ensure patient privacy and improve care. Regulatory remedies may be best suited to tackle external impediments to care such as the insurance and legal systems, while technological interventions may be most appropriate for issues stemming from the lack of inter-institutional communication.

In terms of future work on the topic of mental health, information and technology, we have not adapted our findings into detailed design recommendations; however, future studies on this topic could help create tools and platforms that account for local context and barriers in important ways. Similarly, while we have outlined high-level policy concerns based on our findings, future research could address the topic of mental health, data, and information policy in more depth. Such studies are especially critical in other national contexts, where both the legal and health care landscapes may vary. We encourage more research that can develop policy recommendations in conversation with grounded, holistic accounts of information sharing, mental health, and everyday life.

Acknowledgements

This project would not have been possible without support and collaboration from the Creative Resilience Collective. We are also grateful to providers who shared their perspectives on mental health care information seeking in Philadelphia, and to students in the Spring 2018 course of Theories and Techniques in Qualitative Methods at the Annenberg School at the University of Pennsylvania for conducting interviews with participants. Shane Ferrer-Sheehy provided research support, and the anonymous reviewers offered generous feedback.

About the authors

Jessa Lingel is an Associate Professor at the Annenberg School for Communication and the Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Program at the University of Pennsylvania. Her contact address is jlingel@asc.upenn.edu

Megan Bogia is a PhD student at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Her research interests centre on higher education's public roles and responsibilities in a democracy. She can be contacted at mbogia@g.harvard.edu.

Chloé Nurik is a PhD/JD candidate at the Annenberg School for Communication and the University of Pennsylvania Law School. Her research interests centre on the impact of communication policies and laws, business ethics, and media self-regulation on historically marginalised groups and communities. She can be contacted at chloe.nurik@asc.upenn.edu.

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Alvidrez, J. (1999). Ethnic variations in mental health attitudes and service use among low-income African American, Latina, and European American young women. Community Mental Health Journal, 35(6), pp.515-530. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018759201290

- Ankem, K., Turpin, J. & Ankem, K., Turpin, J. & Uppala, V. (2016). Physician adoption of electronic health records: a visualisation of the role of provider and state characteristics in incentive programme participation. Information Research, 21(2), paper 715. http://InformationR.net/ir/21-2/paper715.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2FWlLQq)

- Baldwin, N. S., & Rice, R. E. (1997). Information‐seeking behavior of securities analysts: Individual and institutional influences, information sources and channels, and outcomes. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 48(8), 674-693. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199708)48:8<674::AID-ASI2>3.0.CO;2-P

- Balka, E. & Star, S.L. (2016). Mapping the body across diverse information systems: shadow bodies and how they make us human. In G.C. Bowker, S. Timmermans, A.E. Clarke, & E. Balka, (Eds.). Boundary objects and beyond: working with Leigh Star. (pp.417–434). MIT Press,

- Balka, E., Bjorn, P., & Wagner, I. (2008). Steps toward a typology for health informatics. In CSCW '08: Proceedings of the 2008 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work (pp. 515-524). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/1460563.1460645

- Balka, E., Whitehouse, S., Coates, S. T., & Andrusiek, D. (2012). Ski hill injuries and ghost charts: socio-technical issues in achieving e-health interoperability across jurisdictions. Information Systems Frontiers, 14(1), 19-42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-011-9302-4

- Becker, M. C. (2001). Managing dispersed knowledge: organizational problems, managerial strategies, and their effectiveness. Journal of Management Studies, 38(7), pp.1037-1051. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00271

- Bishop, T. F., Press, M. J., Keyhani, S., & Pincus, H. A. (2014). Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry 71(2), pp.176-181. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862

- Bourgeois, F. C., Olson, K. L., & Mandl, K. D. (2010). Patients treated at multiple acute health care facilities: quantifying information fragmentation. Archives of internal medicine, 170(22), 1989-1995. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.439

- Brailer, D.J. (2005). Interoperability: the key to the future health care system. Health Affairs, 24(1), W5.19–W.5.21. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.w5.19

- Bronstein, J. (2014). Is this OCD?: Exploring conditions of information poverty in online support groups dealing with obsessive compulsive disorder. In Proceedings of ISIC, the Information Behaviour Conference, Leeds, 2-5 September, 2014: Part 1, (paper isic16). http://InformationR.net/ir/19-4/isic/isic16.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://web.archive.org/web/20191107103931/http://www.informationr.net/ir/19-4/infres194.html)

- Brown, T. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard Business Review, 86(6), pp.84-92.

- Bryant, J., Matthews, G., & Walton, G. (2009). Academic libraries and social and learning space. A case study of Loughborough University Library, UK. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 41(1), 7-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000608099895

- Cairns, P., Pandab, P., & Power, C. (2014). The influence of emotion on number entry errors. In ACM Proceedings of 2014 SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, 26 April- 1 May 2014. (pp.2293-2296). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557065

- Corbin, J. M. & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. (4th ed.) SAGE Publications.

- Corrigan, P. W. (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist 59(7), 614-625. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614

- Corrigan, P.W., Druss, B. G., & Perlick, D. A. (2014). The impact of mental illness stigma on seeking and participating in mental health care. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 15(2), 37-70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100614531398

- County Health Rankings and Roadmaps. (2019). Philadelphia. University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/pennsylvania/2019/rankings/philadelphia/county/factors/overall/snapshot (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3olwTrq)

- Curtis, S., Gesler, W., Fabian, K., Francis, S., & Priebe, S. (2007). Therapeutic landscapes in hospital design. A qualitative assessment by staff and service users of the design of a new mental health inpatient unit. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 25(4), pp.591-610. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1312r

- Drake R. E., & E. Latimer, E. (2012). Lessons learned in developing community mental health care in North America. World Psychiatry 11(1), pp.47-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.01.007

- Ebeling, M. (2016). Health care and big data: digital specters and phantom objects. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Edwards, D., Burnard, P., Coyle, D., Fothergill, A., & Hannigan, B. (2000). Stress and burnout in community mental health nursing: a review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 7(1), 7-14. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2000.00258.x

- Ernala, S. K., Rizvi, A.F., Birnbaum, M. L., Kane, J. M., & de Choudhury, M. (2017). Linguistic markers indicating therapeutic outcomes of social media disclosures of schizophrenia. In Proceedings of ACM on Human-Computer Interaction (CSCW ‘17), Denver, CO, 6-11 May 2017 (pp. 43:1-43:27). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3134678

- Gary, F. A. (2005). Stigma: Barrier to mental health care among ethnic minorities. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 26(10), pp.979-999. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840500280638

- Gui, X., & Chen, Y. (2019). Making health care infrastructure work: unpacking the infrastructuring work of individuals. In ACM Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, Scotland, 4-9 May 2019 (pp.458:1-458:14). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300688

- Herek, G. M., & Garnets, L. D. (2007). Sexual orientation and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 353-375. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091510

- Heun-Johnson, H., Menchine, M., Goldman, D., & Seabury, S. (2017). The cost of mental illness: Pennsylvania facts and figures. Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics.

- Kaiser, D. J., & Karuntzos, G. (2016). An examination of the workflow processes of the screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT) program in health care settings. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 60, 21-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2015.08.001

- Kakuma, R., Minas, H., van Ginneken, N., Poz, M. R. D., Desiraju, K., Morris, J. E., Saxena, S., & Scheffler, R. M. (2011). Human resources for mental health care: current situation and strategies for action. The Lancet, 378(9803), 1654-1663. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61093-3

- Klenk, S., Dippon, J., Fritz, P., & Heidemann, G. (2011). A personalised medical information system. In ACM Proceedings of the 3rd Workshop on Software Engineering in Health Care, Honolulu, HI, 21-28 May 2011 (pp.9-12). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org//10.1145/1987993.1987997

- Lederman, R., Wadley, G., Gleeson, J. Bendall, S., & Álvarez-Jiménez, M. (2014). Moderated online social therapy: designing and evaluating technology for mental health. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 21(1), 5:1-5:26. https://doi.org/10.1145/2513179

- Liberati, E. G, Tarrant, C., Willars, J., Draycott, T., Winter, C., Chew, S., & Dixon-Woods, M. (2019). How to be a very safe maternity unit: an ethnographic study. Social Science & Medicine, 223, 64-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.035

- Mechanic, D. (2012). Seising opportunities under the Affordable Care Act for transforming the mental and behavioral health system. Health Affairs, 31(2), 376-382. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0623

- Modlin, H. C., Benson, R. E., & Porter, L. (1976). Mental health centers and the criminal justice system. Psychiatric Services, 27(10), 716-719. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.27.10.716

- O'Kane, A. A., & Mentis, H. (2012). Sharing medical data vs. health knowledge in chronic illness care. In ACM CHI'12 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, TX, 5-10 May, 2012 (pp. 2417-2422). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2212776.2223812

- Ortega Egea, J.M., Román González, M.V., & Recio Menéndez, M. (2010). Profiling European physicians' usage of eHealth services. Information Research, 16(1), paper 467. http://InformationR.net/ir/16-1/paper467.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://web.archive.org/web/20191107104112/http://www.informationr.net/ir/16-1/infres161.html)

- Paris, M. & Hoge, M. A. (2010). Burnout in the mental health workforce: a review. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research 37(4), 519-528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-009-9202-2

- Pettigrew, K. E., Fidel, R., & Bruce, H. (2001). Conceptual frameworks in information behavior. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 35, 43-78.

- Pratt, W., Unruh, K., Civan, A. & Skeels, M.M. (2006). Personal health information management. Communications of the ACM, 49(1), 51-55. https://doi.org/10.1145/1107458.1107490

- Provenanzo, C. (2016, October 20). Most states with little access to mental health resources also have the highest incarceration rates. Business Insider. http://static7.businessinsider.com/little-mental-health-resources-highest-incarceration-rates-2016-10

- Ramsten, C., Marmstål Hammar, L., Martin, L. & Göransson, K. (2017). ICT and intellectual disability: a survey of organizational support at the municipal level in Sweden. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 30(4), 705–713. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12265

- Rothschild, N. and Aharony, N. (2016). Empathetic communication among discourse participants in virtual communities of people who suffer from mental illnesses. Information Research, 21(1), paper 701. http://InformationR.net/ir/21-1/paper701.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://web.archive.org/web/20191220224058/http://www.informationr.net/ir/21-1/infres211.html

- Sapa, R., Krakowska, M. & Janiak, M. (2014). Information seeking behaviour of mathematicians: scientists and students. Information Research, 19(4), paper 644. http://InformationR.net/ir/19-4/paper644.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://web.archive.org/web/20191220224058/http://www.informationr.net/ir/19-4/infres194.html

- Saxena, S., Thornicroft, G., Knapp, M., & Whiteford, H. (2007). Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. The Lancet, 370(9590), 878-879. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2

- Schaefer, J. D., Caspi, A., Belsky, D. W., Harrington, H., Houts, R., Horwood, L. J., Hussong, A., Ramrakha, Poulton, R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2017). Enduring mental health: prevalence and prediction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 126(2), 212-224. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000232

- Schout, G., de Jong, G., & Zeelen, J. (2011). Beyond care avoidance and care paralysis. Theorising public mental health care. Sociology 45(4), pp.665-681. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511406591

- Snowden, L.R. (2003). Bias in mental health assessment and intervention: theory and evidence. American Journal of Public Health 93(2), 239-243. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.2.239

- Solomon, J., Scherer, A. M., Exe, N. L., Witteman, H. O., Fagerlin, A., & Zikmund-Fisher, B. J. (2016). Is this good or bad? Redesigning visual displays of medical test results in patient portals to provide context and meaning. In ACM Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, 7-12 May 2016 (pp. 2314-2320). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2851581.2892523

- Sommers, B. D., Gawande, A. A., & Baicker, K. (2017). Health insurance coverage and health - what the recent evidence tells us. The New England Journal of Medicine, 377(6), 586-593. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb1706645

- Steele, L., Dewa, C., & Lee, K. (2007). Socioeconomic status and self-reported barriers to mental health service use. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 52(3), 201-206. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370705200312

- Taneva, S., Waxberg, S., Goss, J., Rossos, P., Nicholas, E., & Cafazzo, J. (2014). The meaning of design in health care: Industry, academia, visual design, clinician, patient and HF consultant perspectives. In CHI'14. Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, 26 April- 1 May 2014 (pp. 1099-1104). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2559206.2579407

- Teplin, L. A. (1984). Criminalizing mental disorder: the comparative arrest rate of the mentally ill. American Psychologist, 39(7), 794-803. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.39.7.794

- Tracy, S. J. (2012). Qualitative research methods: collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. John Wiley & Sons.

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2018). Quick facts: Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/philadelphiacountypennsylvania (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200206213537/https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/philadelphiacountypennsylvania)

- Wang, R. Wang, W., DaSilva, A., Huckins, J. F., Kelley, W. M., Heatherton, T. F., & Campbell, A. T. (2018). Tracking depression dynamics in college students using mobile phone and wearable sensing. In Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, Singapore, 8-12 October 2018. (pp.43:1-43:26). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3191775

- Wilcox, L., Patel, R., Chen, Y. & Shachak, A. (2013). Human factors in computing systems: Focus on patient-centered health communication at the ACM SIGCHI Conference. Patient Education and Counseling 93(3), 532-534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.09.017

- Williams, A. D. (2016). Harnessing the quantified self movement for optimal mental health and wellbeing. In LTA '16: Proceedings of the first Workshop on Lifelogging Tools and Applications, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 15-19 October 2016. (p.37). https://doi.org/10.1145/2983576.2983585

- Wood, V. J., Curtis, S. E., Gesler, W., Spencer, I. H., Close, H. J., Mason, J., & Reilly, J. G. (2013). Creating ‘therapeutic landscapes’ for mental health carers in inpatient settings: A dynamic perspective on permeability and inclusivity. Social Science & Medicine, 91, 122-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.09.045

How to cite this paper

Appendix-Interview guide

Our interview guide was developed in collaboration with the Creative Resilience Collective, a local activist group committed to providing mental health resources for underserved populations in Philadelphia.

- What does your typical work day look like?

- Think about the last one you were able to help someone seeking mental health services. What was the process for responding to their needs from the beginning to the end?

- Tell me about a client or a student that you’re working with who is really struggling to find care.

- What are your thoughts about mental health and stigma here in Philadelphia?

- Do you ever refer clients to other organisations’ services? If so, why?

- Do you ever lack information that could make your work easier? In what kind of situations does this occur? How might these problems be solved?

- What’s the most trustworthy organisation you refer people in Philadelphia to and why?

- If you had a magic wand, what would you change about how mental health care is provided in Philadelphia?