How experiences reported on intermediary information seeking from inter-disciplinary contexts can inform a study on competitive intelligence professionals

Tumelo Maungwa, and Ina Fourie.

Introduction. Intermediary and proxy searching, where one person searches on behalf of another, are noted in information science, health sciences and library science (e.g., reference work and early day online searching), professional workplace practices (e.g., lawyers, nurses) and everyday life contexts (e.g., caregivers). It is also observed within the competitive intelligence process, which involves collecting intelligence data from business environments on behalf of senior management and clients. Many problems occur in competitive intelligence intermediary information seeking that might be addressed by examining interdisciplinary contexts.

Method. Literature searches were conducted in key library and information science, health science and law databases. A total of 136 publications were manually selected and analysed for a scoping literature review.

Analysis. Thematic analysis was applied.

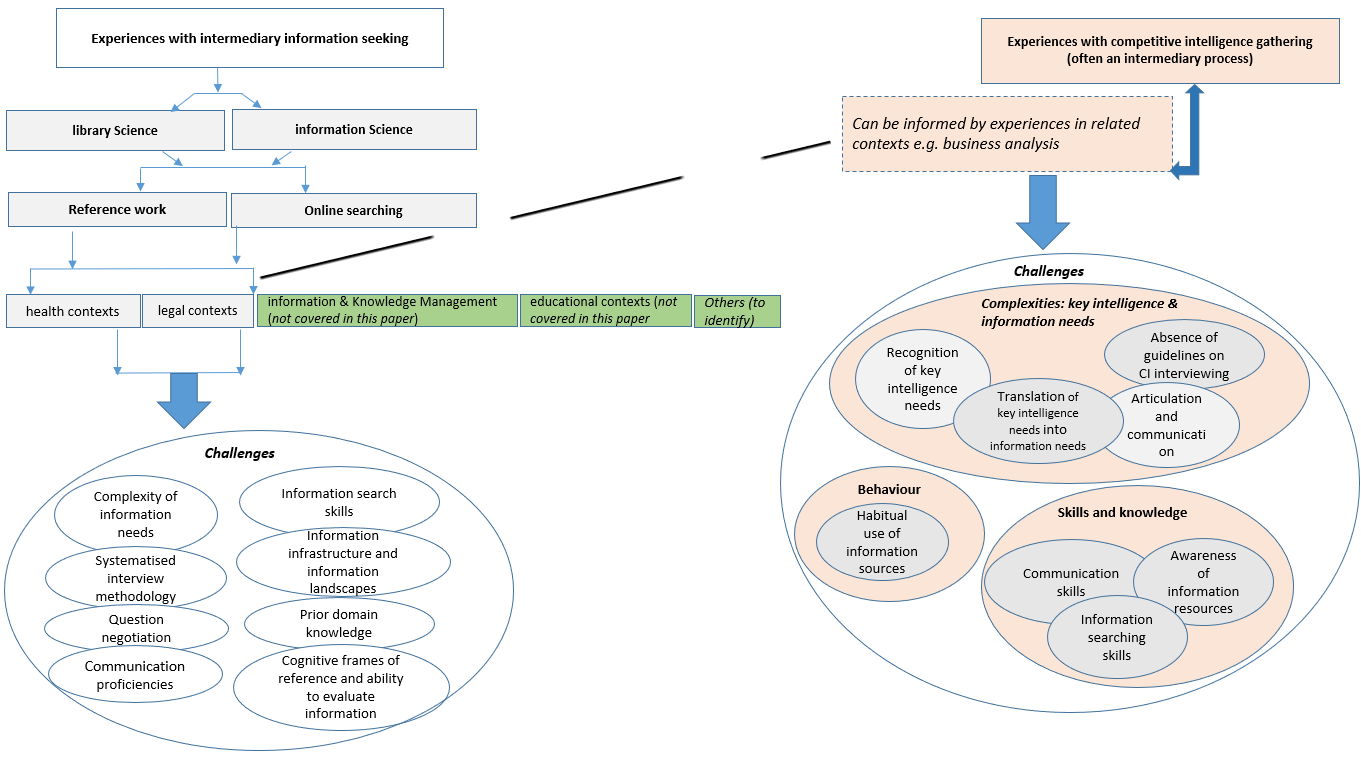

Results. Challenges emerging from the thematic analysis are disaggregated into facets of intermediary information seeking (e.g., skills in question negotiation and information needs assessment, search heuristics and knowledge of information infrastructures).

Conclusion. Systematised intermediary practices (e.g., application of appropriate question negotiation techniques, expanded knowledge of information infrastructures and landscapes, competitive intelligence domain knowledge and communication) can enhance intermediary information seeking, and should be investigated in competitive intelligence.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.47989/irisic2023

Introduction and rationale

Intermediary information seeking, also known as proxy and mediated information seeking or searching, refers to a process where one person searches on behalf of another. Although limited, research on intermediary information seeking, as noted by Taylor (1998), Savolainen (2010), Case and Given (2016), Buchanan, et al., (2019) has featured over many years. In the database, Library and Information Science (LISA), the first article using intermediary information seeking was only published in Hungarian in 1983 by Balazs. The term proxy was first used in an article by Parker in 1989 which focused on managing information systems. Both terms gradually gained acceptance in the library and information science literature on online searching and later information behaviour (Case, et al., 1986; Kuhlthau, et al., 1992).

In the early days of online searching, before the availability of CD-ROM (compact disc, read-only-memory), databases and the internet, librarians searched on behalf of patrons on subscription databases that were difficult and expensive to search such as the Dialog databases (Keenan, et al., 1980; Kuhlthau, et al., 1992). Many papers on good practices, skills, knowledge and personal characteristics and the importance of educating and training librarians and information specialists as intermediaries appeared at the time in the library and information science literature (Brettle, et al., 2006; Addison, et al., 2010). Experts, often writing regular columns on the topic, included Barbara Quint (2016) and Mary Ellen Bates (2019). (These are only a few of the many contributions they published). There was also a strong body of literature on reference work (Hanson, 2004; Harmeyer, 2010; Saunders, 2016) and reference interviews (Allcock, 2000; Johnston, 2010; Saunders, 2016) guiding librarians (for purposes of this paper, this is the preferred term that will include information professionals, library and information [LIS] professionals, information specialists and references workers).

Information seeking is a process that involves the purposive seeking for information due to a need to satisfy a goal or objective (Wilson, 2000, p.49) or fill a gap of knowledge (Cole, 2011). As a field of study, it examines the methods people use to acquire information, which also includes how and where people find solutions to information problems (McKenzie, 2003, p. 27; Burke, 2007, p. 3-14). Wilson (1999, p. 263) defines information searching as a subset of information seeking, which is concerned with the interactions between information users and computer-based systems. If the information seeking process is conducted by one person on behalf of another, many challenges arise which can compromise effective and efficient information retrieval including high recall and high precision (Allen, 1998; Asan and Montague, 2014); this is on top of the challenges people normally experience when searching for information for their own benefit. Intermediary information seeking also presents the challenges to elicit information needs and awareness of the scope of literature searching required. These could be impacted by several factors including the capability to prompt appropriate questions, familiarity with available information resources and stigmatisation where people may not be comfortable to reveal the true nature of their need for information (Ronan, 2003; Brown, 2008). A strong body of literature thus developed in library and information science on doing searches on behalf of another person, challenges to expect and dealing with such challenges. Even the skills, knowledge and personality to interrogate expensive online databases were addressed (Myers, 1990; Alcock, 2000; Jokic, 1997; Hussien and Mokhtar, 2018). Gradually intermediary information seeking (and related terms) were also introduced into the health sciences where caregivers and health professionals may seek on behalf of patients (Abrahamson, et al., 2008) and legal contexts where lawyers have been noted to search for information on behalf of their clients (Kuhlthau and Tama, 2001). Although there is not a strong body of literature in these fields, some of the reported experiences may enhance understanding of intermediary information seeking.

The traditional processes of online searching and reference work seen form a library and information science perspective and the activities involved when a competitive intelligence professional collects intelligence in business environments on behalf of the decision makers such as senior managers or contract clients (i.e., the competitive intelligence process) entail many information activities that fall under the umbrella terms of information behaviour and information practice (Savolainen, 2010; Case and Given, 2016). Jin and Bouthillier (2008, p.5) confirm that the construct of the competitive intelligence process involves intensive information behaviour activities. These include activities of planning and direction, data collection, analysis, dissemination and feedback (Muller, 2002; Frion and Yzquierdo-Hombrecher, 2009; Strauss and Du Toit, 2010; Calof, et al., 2015; Maritz and Du Toit, 2018). Calof and Skinner (1998), Muller (2002), Bose (2008) and Salguero, et al., (2019) emphasise that the competitive intelligence activities that are labelled as phases are linked and interrelated; the output of one phase serves as the input of the next and the overall output serves as a tool for decision making.

Many challenges and failures of competitive intelligence has been noted often with serious consequences (Jensen, 2012; Tsitoura and Stephens, 2012; Thatcher, et al., 2015). Factors causing failure include poor articulation of information needs, lack of conceptual understanding of competitive intelligence, lack of access to information, and the process of intermediary information seeking (Tao and Prescott, 2000; Dishman and Calof, 2008; Strauss and Du Toit, 2010; Bartes, 2015; Tsitoura and Stephens, 2012; Maungwa and Fourie, 2018). Maungwa and Fourie (2018) categorise key failures under errors related to information activities, errors attributed to individual competencies and errors caused by organisational aspects. They emphasise the challenges caused by intermediary information seeking in the competitive intelligence process. One of their participants for example noted, ‘I keep the bigger picture to myself and task the team [competitive intelligence professionals] in specifics’. This makes it difficult for the person (intermediary information seeker) to fully conceptualise the true information need. Although not always explicitly stated, failure due to intermediaries, is implied in many other studies (Strauss and Du Toit, 2010; Nenzhelele, 2015). The book by Carr (2003) on information seeking for competitive intelligence professionals should be a signal that specialised skills are needed. Competitive intelligence professionals often have sales, planning or marketing research titles with few referred to as librarians or information specialists (Sutton, 1988). These points to limited or no training in advanced information seeking, apart from basic academic information literacy training (Maungwa, 2017). Such training is not on the same level as has been extensively discussed in the training of librarians and information specialists in online searching – especially early day training where they were trained as information intermediaries (Isenstein, 1992; Jennerich and Jennerich, 1997).

Consideration of the prominence of information activities, and the intermediary information process in discussions of competitive intelligence failures as well as insights from decades of work in library and information science and other fields and contexts where intermediary information seeking has been noted (e.g. health science, law), might deepen insight of challenges of intermediary information seeking by competitive intelligence professionals and pave the way for an in-depth information behaviour competitive intelligence study.

The purpose of this paper is thus to address the research question:

How can experiences of intermediary information seeking in other contexts and informed by the practices of other disciplines guide a study on the challenges competitive intelligence professionals experience with intermediary information seeking?

- RQ1: what can be learned about intermediary information seeking from the literature of library science, information science, information behaviour, health sciences and law?

- RQ2: How can such knowledge guide the choice of key themes to investigate in an information behaviour study of intermediary information seeking in competitive intelligence?

Apart from the introduction sketching the rationale for the paper, a clarification of key concepts, review of the method (i.e., a scoping literature review), findings from a thematic analysis, discussion and interpretation of findings, recommendations for practice and theory related to intermediary information seeking in competitive intelligence and a conclusion will be covered.

Clarification of concepts

Four terms are key to understanding intermediary information seeking from various disciplines with the focus being on informing the competitive intelligence process (i.e., gathering of intelligence).

Competitive intelligence: Bergeron and Hiller (2002, p. 355) define competitive intelligence (as process) as the collection, transmission, analysis and dissemination of publicly available, ethically and legally obtained relevant information, as a means of producing actionable knowledge (i.e., intelligence which organisations can use to make strategic decisions). Competitive intelligence includes the monitoring of the external environment for opportunities, threats and developments (Straus and Du Toit, 2010, p. 302).

Competitive intelligence professional: For this paper, we accept competitive intelligence professionals as agents who conduct the competitive intelligence process, and who assume the responsibility for intermediary information seeking. The terms competitive intelligence professional and competitive intelligence practitioner are often used interchangeably (Calof and Wright, 2008; Garcia-Alsina, et al., 2013; Jin and Ju, 2014). This paper will standardise on the term competitive intelligence professional.

Information behaviour: For purposes of this study, information behaviour refers to all information-related activities and encounters, including information seeking, information searching, browsing, recognising and expressing information needs, information encountering, information avoidance and information use (Fourie and Julien, 2014 – acknowledging definitions by well-known researchers such as Donald Case, Reijo Savolainen and Tom Wilson). In the context of a paper on intermediary information seeking, this interpretation can also allow for information practice. According to Case (2016, p. 99-100) the term information practice has been put forward as an alternative to information behaviour. Wilson (2000) views information behaviour as an umbrella term under which information practice falls under. The term information practice has also been noted in the work of Tabak (2014), Olsson (2016) and more recent work of Allen, Savolainen also argues that the qualitative research on information behaviour be called the study of information practice. According to Savolainen the major difference between the two concepts is that in the discourse on information behaviour, the dealing with information is primarily seen to be triggered by needs and motives, while the discourse on information practice accentuates the continuity and habitualisation of activities affected and shaped by social and cultural factors. The Wilson and Savolainen (2010) debate can shed more light on the differences (Lanham, 2009). Although the value of both concepts are acknowledged, this paper will keep to information behaviour – but, pending further work on the information behaviour of competitive intelligence professionals per se, we might opt for the term information practice.

Intermediary information seeking: Intermediation refers to a human or non-human part that assists people in processing information (Jinkook and Jinsook, 2005, p.95). The collection, organisation and distribution of information can also be included. According to McKenzie (2003, p.27) intermediary information seeking refers to the process were people interact with information sources through the initiative of another agent, either the information source or some other gatekeeper or intermediary. This paper will therefore accept intermediary information seeking as a process that involves a dialogue or interaction between a patron with an information need and an agent (information scientist, a reference or special librarian, an information broker, an online searcher [not as end-user] or an information officer) who possess the skills and capabilities to collect, organise and distribute information (McKenzie, 2003; Jinkook and Jinsook, 2005; Buchanan, et al., 2019). In clarifying intermediary, it is important to also note the term disintermediation, which according to Fourie (1999, p.10) refers to the finding of information by an end-user without consulting a third party. This is the alternative to intermediary information seeking. Although the terms proxy and intermediary information seeking are often used interchangeably, this paper will standardise on the term intermediary information seeking.

Method

Since competitive intelligence is characterised by professionals searching on behalf of decision-makers, it seemed relevant to search disciplines and contexts where intermediaries have been reported to search for information on behalf of clients, patrons and patients (e.g., Harter, 1986; Strauss and Du Toit, 2010; Coonin and Levine, 2013; Salguero, et al., 2019). A comprehensive series of literature searches were thus conducted to trace publications relevant to intermediary information seeking from a variety of disciplines and workplace and everyday life contexts; most prominent were health sciences, library science, information science and law. Literature on online searching and the process of question-negotiation as key to successful intermediary searching was also included (Trivison, et al., 1987; Tyner, 2014). The scope of the literature searches is depicted in Table 1.

| Detailed explanation of the method | |

|---|---|

| Key databases consulted | Web of Science, Library Information Science & Technology Abstracts (LISTA), Library and Information Science Abstracts (LISA), MEDLINE, PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Emerald Insight and Law Review Commons |

| Disciplines | Information science (specifically information behaviour as sub-discipline), library science, health sciences and law |

| Key terms | intermediary (information) seeking; intermediary (information) searching, mediated (information) seeking, online searching, question negotiation, reference interviews |

| Search indexes | Subject heading, abstract, document title; in addition, searches were conducted on known authors who published on online searching e.g. Quint (2016), Bates (2019) |

| Sources retrieved | 560 |

| Criteria for selection | Type of publication: scholarly research articles; opinion pieces by experts (e.g., online searchers), book chapters, English language only, no date restriction (much of the relevant work was published in the early days of online searching) |

| Sources analysed | After scanning the titles and abstracts of the retrieved sources, the following sources (136) were considered for analysis based on their relevance to the research statement: Articles: 123 Book chapters: 13 |

Thematic analysis was used to identify facets related to the research question. Thematic analysis refers to a method of analysing, reporting and identifying patterns and focuses on describing both implicit and explicit ideas within data (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Clarke and Braun, 2013; Guest, et al.,2012). However, there have been criticism of this approach due to a lack of concise guidelines for researchers employing such methods (Alhojailan, 2012; Nowell, et al., 2017). This has led to some authors omitting the procedures of how they analysed their data. Our analysis was driven by the theoretical interest in finding experiences of intermediary information seeking across interdisciplinary contexts that might direct a study on intermediary information seeking in competitive intelligence. Following a rigorous skimming of the abstracts and focus of each of the references, we analysed selected sources to identify themes that can answer the research question: How can experiences of intermediary information seeking in other contexts and informed by the practices of other disciplines guide a study on the challenges competitive intelligence professionals experience with intermediary information seeking? Repeated reading of the selected sources led to the identification of core themes. The selection of the consulted information sources was subjective and greatly influenced by the second authors training and experience as a librarian and lecturer for information retrieval, online searching and information literacy.

Insights from the thematic analysis

Much has been reported form library and information science, health science and law on challenges that can be disaggregated into facets of intermediary information seeking (e.g., reference interviews, reference appropriate communication, question negotiation, knowledge of information infrastructures and information horizons, knowledge of search strategies and search heuristics; knowledge of the intricacies of online searching, the characteristics of a good online searcher and domain knowledge). The authors considered literature from library and information science that addressed challenges experienced by librarians searching for information on behalf of a patron (e.g., Behrens, 2000; Saunders and Jordan, 2013; Hussien and Mokhtar, 2018). From Health sciences, the authors considered literature that focused on challenges faced by health-care professionals (e.g., nurses) searching for information on behalf of patients and non-professionals (e.g., mothers) searching for health-related information on behalf of family members such as children or parents (Burnham and Perry, 1996; Salz, et al., 2014; Prakasan, 2013). Some of the health context literature were written by authors specialising in library science or information science e.g. Fourie and Julien (2014) and Buchanan, et al. (2019) reporting on intermediation in healthcare. From law the authors considered literature on lawyers seeking for legal representative information for their clients (Baird, 1978; Sherr, 1986; Fambasayi and Koraan, 2018). Based on the nature of their work, lawyers have been described by some authors as intermediaries, albeit, not in the same sense as information intermediaries as defined in our operational definition (Dzienkowski, 1996; Fambassayi and Koraan, 2018). Lawyers’ intermediary practices, information needs and information seeking are greatly influenced by the nature of their work (O’Leary and Cooper, 1981; Reynolds, 1994; Forrest and Robb, 2000). For all three disciplines and disciplinary contexts, the people who act as intermediaries are influenced by their training in the specific discipline and for their job. Librarians receive extensive training in reference work (Coonin and Levine, 2013; Hussein and Mokhtar, 2018), doctors and nurses are trained in health communication and patient interviews (Feliciano, 1984; Lichstein, 1990;) and lawyers are trained in client interview and counselling (Baird, 1978; O’Leary and Cooper, 1981).

Seven themes were deduced through the thematic analysis for the requirements for successful information intermediary seeking. These include: complexity of information needs; systematised methodology: question-negotiation; systematised methodology: interviews; search skills; information infrastructures; domain knowledge and social-cognitive understanding of the information need(s); knowledge of information evaluation and selection; communication proficiencies (Taylor, 1988 ; Harter, 1986; Sonnenwald, 1999; Savolainen, 2006; Cole, 2011; Bates, 2019).

Complexity of information needs

The complexity and the recognition of information needs are widely acknowledged in information science theoretical literature (Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2012) and information behaviour studies (Case and Given, 2016). It has been noted that information needs are often not recognised and remains as dormant or latent information needs (; Wilson 2000). This refers to the fact that people do not always fully recognise the scope of their information needs and thus do not express such information needs. For success in searching information, every effort needs to be taken to get the person needing information to disclose dormant and latent information needs. Issues regarding the complexity of information needs were seldom noted in the literature consulted on intermediary information seeking or online searching. Forsetlundand and Bjørndal (2001) and Nicholas and Herman (2010) are amongst the few who have noted the challenges of unrecognised information needs. Various techniques can be used to stimulate the recognition of dormant information needs. Shenton’s (2007) work on the Johari window can address problems with the identification and expression of information needs and thus also intelligence needs (this is the term used in competitive intelligence literature to refer to the information needs of the organisation as expressed by decision makers). Question-negotiation might also be useful but is more focused on establishing an accurate and clear articulation of an information need(s). Authors writing from a competitive intelligence standpoint including Muller (2002), Nasri (2011) and Du Toit (2015), have commented on the complexity of articulating key intelligence needs (organisational information needs). Such key intelligence needs must then still be interpreted as information needs. According to Du Toit (2007) (coming from an information science background) the information needs of senior management may at times be subconscious, which presents a major challenge.

Question negotiation

During interviews such as reference interviews, people share their needs for information with the intermediary. Due to the complexity of information needs as set out under the preceding theme, a deeper, more nuanced systematised knowledge and understanding is however, required to deal with the full challenge of complex information needs. Tseminal work on question-negotiation to determine information needs has been widely cited in library and information science and especially studies of information behaviour (Case and Given, 2016).

Both Taylor (1998) and Harter (1986) reported on the challenges to determine information needs and the levels of communication involved. Katz (1978, p.90) explain question-negotiation as ‘one person tries to describe for another person not something he knows, but rather something he does not know’. Freeman, argue that the articulation of needs is required in order to determine the magnitude of a problem, or to verify that a problem exists. According to Taylor (1998) when seekers of information in a library go through an intermediary, they must develop their question through four levels; (1) visceral needs, the actual but unexpressed need for information; (2) conscious need, conscious description of the need; (3) formalised need, the formal statement of the need; (4) compromised need, the question as presented to the information system.

According to Dorner, et al., (2015) unexpressed information needs, usually remain unexpressed because it is difficult to convert it into terms that others will understand. The studies by Buchanan, et al. (2019) and Schilderman (2002) were among the few that revealed that voluntary sector professionals who provide heath related information to young mothers, had difficulties articulating the information needs due to the mothers’ behaviour of secrecy and deception, which was a result of a lack of trust on the mothers’ side. Eberle (2005) reports similar findings from a study that explores reference interviews in mental health hospitals. The results of the study showed that due to a stigma issue surrounding certain medical conditions, patrons were reluctant to share their true information needs with health professionals. This is something that might be addressed in question negotiation. Authors writing from the health sciences, have also noted the difficulties of articulating information needs (Timmins, 2006; Ormandy, 2011; Beautyman and Shenton, 2009) various studies cited by Case and Given, 2016). From a competitive intelligence context, the articulation of intelligence needs can be interpreted from the work of Taylor (1998) on question-negotiation and the levels ranging from visceral (compromised awareness of a need) to formal. When librarians act as intermediary, question negotiation normally takes place during the reference interview. The competitive intelligence literature does not mention question-negotiation; this may not be the term adopted in the discipline and alternatives were not noted.

Systematised interviewing methodology

Library science presents a considerable body of books and articles on the intricacies and methodology of reference interviews (Harter, 1986; Nicholas and Herman, 2010; Saunders, 2016). These are interviews librarians and information specialists conduct to search on behalf of other people. Disciplines have different naming conventions; health sciences literature refers to patient interviews (Burnham and Perry, 1996; Prakasan, 2013) and law to client interviews and counselling (Baird, 1978; Sherr, 1986; O’Leary and Cooper, 1981; Forrest and Robb, 2000)

From a library perspective, various formats for conducting reference interviews have been noted including face-to-face, chat reference and virtual reference interviews (Ronan, 2003; Eberle, 2005; Saunders, 2016). Smith (2008) and Nicholas and Herman (2010) noted various challenges that impacts on the quality of reference interviews such as complex and trivial questions posed by the patron and communication difficulties. Some practitioners have also referred to the value of online search interviews; they have stressed the very high expectations for appropriate skill sets required by such intermediaries (Quint 2016; Bates, 2019). During the early days of online searching it became evident that some sort of pre-search interview was needed between online searchers and their patrons (Harter, 1986). Consequently, some of the techniques used for reference interviews were adopted for pre-search (online) interviews. Even so, there were still many challenges. Ramos-Eclevia (2012) who focused on librarians’ perceptions of quality chat reference service (i.e., virtual and digital reference services, using tools such as emails) found that reference interviews are affected by challenges with question types (similar challenges are noted in Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005, which can be complex as well as trivial. The purpose of pre-search interviews was to address such question types and to ensure cost-effective searches of expensive databases (Keenan, et al., 1980). Although such cost factors do not apply anymore to the subscription models used by academic libraries (i.e., they are not paying for each individual search), cost factors might still be a serious factor when pay-as-you-go searches are done on expensive databases or purchasing information sources on an individual basis e.g. individual articles or reports. What is a factor, is the cost of the intermediary’s time spend on searching and wasting time when pursuing documents in spite of the fact that information needs might not have been fully clarified.

Interviewing skills should extend to situations where issues of trust e.g. due to stigma surrounding certain medical conditions might prevent people from fully disclosing their information needs (Schilderman, 2002; Eberle, 2005; Buchanan, et al., 2019).

The absence of a generally agreed upon systematised methodology for ensuring that librarians, information specialists, lawyers and health care professionals are conducting reference interviews effectively has been mentioned by several authors across disciplines e.g. Schoenfield and Schoenfield (1977), Jahoda (1981), Stieg and Steig (1980), Jennerich and Jennerich (1997), Barton, et al. (2000), Wilkinson (2001), Tatatabai and Shore (2005). As with any professional technique, the conduct of an effective reference interview requires specialised skills. It was not until 1954 when Maxfield in his paper scrutinised the reference interview more carefully and alluded to specific skills that are necessary to the success of the reference interview e.g. librarians should be attentive and listen, or when necessary clarify and amplify exactly what the patron is saying. (These also related to communication proficiency.) Many authors have written on interviewing skills and even understanding cultural nuances (Behrens, 2000; Barton, et al., 2000; Durrance and Fisher-Pettigrew, 2002; Saunders and Jordan, 2013; Tyner, 2014). However, Schoenfield and Schoenfield (1977) concluded that lawyers must not become lost in techniques and details during the client interview and counselling process but should rather generate a flow of accurate information and reach a mutually agreed-upon decision.

Determining the full procedure and skills for reference interviews are challenging. An expert in reference work and reference sources, Katz (1978) argued that sophisticated methods of interrogating patrons are difficult to describe and teach, ‘How does one try to find out what another person wants to know, when the latter cannot describe his need precisely’. In support of this view, Lichstein (1990) mentions that interviewing a patient is one of the most difficult clinical skills to master, which involves both interpersonal skills and the ability to facilitate effective communication. Jennerich and Jennerich (1997) mention that while attention has been given in teaching reference interviews and developing guidelines, the library community has far to go before reference skills are an integral part of intermediary information seeking, which also includes aspects of question-negotiation, knowledge of search strategies and search heuristics (Bates, 1989; Harter, 1986). It is not the intention of this paper to dwell on the skills required, except to confirm that such skills are very important. Interview practices are also noted in competitive intelligence (Strauss and Du Toit, 2010; Salguero, et al., 2019), but these also do not fully address the challenges in competitive intelligence and intermediary information seeking, as it may not be cognisant from the library and information science literature.

Information search skills

Library and information science presents a substantial body of literature on information search skills of librarians (Harter, 1986; Belkin, 1994; Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005; Bates, 2019). According to Harter (1986) search skills encapsulate both search strategies and heuristics. Search strategies refer to the plan or approach for a search problem, while the latter refers to a move made to advance a search strategy (Harter, 1986; Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005). Harter (1986) e.g. suggests a variety of search strategies ranging from building blocks, to successive search strategies and citation pearl growing. Many more can be found in the relevant literature.

Inability to retrieve the desired information due to a lack of search skills has also been noted in the health sciences. In a study by Cairns, et al., (2015) it was found that family members seeking for information on first-episode psychosis on behalf of a loved one, had challenges retrieving the desired information due to the inability to formulate the search strategy, applying inclusion/exclusion criteria within the search process and examining the relationship between key concepts for comparison. A few authors such Elliot and Kling (1997) and Makri, et al. (2008) have commented on the poor information search skills of lawyers. Howaland and Lewis (1990) in their study found that lawyers were unable to efficiently find information on issues that appear on actual legal cases; this was despite all lawyers having received some training on how to use the libraries while in law school. The lack of information searching skills by competitive intelligence professionals is also noted in the competitive intelligence literature (Frion and Yzquierdo-Hombrecher, 2009; Strauss and Du Toit, 2010; Garcia-Alsina, et al., 2013). Murphy (2006) and Strauss and Du Toit (2010) have argued that competitive intelligence professionals should possess vigorous research skills since finding the relevant information is not an easy task. Research skills do, however, imply the rigor of search heuristics and techniques argued for in literature on online searching.

Communication proficiencies

Literature from health, law and library and information science address arguments on communication proficiencies including written as well as verbal communication skills. O’Leary and Cooper (1981), writing from a Health sciences perspective, notes that effective communication skills are the fundamental link between health professionals and patients, which enables the articulation of accurate and complete information needs. Authors writing from a Law perspective, mentioned that effective communication from lawyers influence clients’ satisfaction (Baird, 1978; O’Leary and Cooper, 1981; Prakasan, 2013). Following Taylor’s (1998) seminal work on question negotiation, several fragments of literature have been written about the various facets of communication in establishing the full scope of a person’s information needs, the purpose for information seeking and the context of an information need.

In library and information science communication proficiencies are often related, but not limited to, reference interviews. In his book on online searching Harter (1986) elaborates on the importance of communication in reference interviews. He developed arguments from the work of Shannon and Weaver (1949), noting three levels at which communication challenges can occur that will influence the success of intermediary information seeking: technical, semantic and syntactical levels of communication. These can all hamper understanding of the needs for information. Similar observations are echoed by Dervin (1999), McKenzie (2003), Shenton (2007), Cole (2011) and Coonin and Levine (2013). A study by Brandt and Kracht (2011) takes a similar approach as Harter (1986). They focus on pragmatic errors such as unrecognised errors of interpretation on the side of both the patron and librarian; the librarian might not clearly hear what a patron is saying and instead of asking for clarification, the librarian might settle for the unintended meaning. In addition, Dewdney and Gillian (1996) in their study characterised communication barriers into hearing and understanding, interpretation and phonological errors. Within the competitive intelligence process, communication barriers and errors may also come in to play during the intelligence needs articulation between the competitive intelligence professional and decision makers who might be senior management in a company or clients in the case of companies offering contract services.

Prior domain knowledge

Literature in library and information science as well as the health sciences has reported on how prior domain knowledge (i.e., knowledge of a search topic) improves information search performance in terms of search navigation efficiency, shorter search time and more effective information retrieval (Wilkinson, 2001; Tatatabai, and Shore, 2005; Fox and Duggan, 2013; Luo and Park, 2013). Harter and Hert (1998), Vakkari (1999), Ingwersen and Järvelin (2005) commented on the lack of domain specific knowledge when librarians search on behalf of patrons and their challenges in dealing with search complexity. Chen and Dhar (1991) found that a lack of expertise in a subject area leads to problems with the expression of search topics and search specificity, the use of inappropriate search terms and misinterpretation of the subject headings typically used in databases. Tu (2007) also reported ineffective information retrieval by librarians lacking domain knowledge. From a health perspective Fox and Duggan (2013) and Luo and Park (2013) reported on the challenges faced by intermediaries who lack sufficient health literacy knowledge, i.e., knowledge of health information searching and use of complex information system (Lawless, et al., 2016; Johnson and Case, 2012). An individual’s level of health literacy determines the information base they start with when confronting a health problem and the type of information they retrieve (Johnson and Case, 2012). Abrahamson, et al., (2008) found that intermediaries who lack health literacy found it difficult to use information systems to locate health information, they were uncertain of their search statements and they struggled to evaluate the trustworthiness and quality of the obtained information. Tu (2007), reporting on virtual health reference services, found that public librarians are generalists and usually not trained in health information seeking; hence their knowledge on consumer health is limited. This compromised the quality of their searchers. In fact, Wessel, et al. (2003) found that public librarians were often uncertain which reference books to use to answer questions on diseases. Jokic (1997) also revealed that difficulties experienced by librarians using known indexing terms include a need for extensive knowledge on the subject area, the information system and the classification scheme. At times, library patrons have been noted to require information that is not recorded in traditional literature sources, such as information about future events, trade secrets and classified government information, typically referred to as grey literature (Katz, 1978; Schöpfel, and Farace , 2009). For competitive intelligence, grey literature might include federal and state legislation, future technology advancements and investments made by various industry organisations (Blenkhorn and Fleisher, 2001; McGonagle and Vella, 2002). Competitive intelligence professionals might not only lack knowledge of the topic(s) covered by an information need(s), but they might also experience challenges in finding grey literature.

Information infrastructures and information landscapes

The importance of knowledge of disciplinary information infrastructures has been widely noted in library science and especially training in reference work (Katz, 1978; Behrens, 2000). Inadequate knowledge of available information sources (i.e., information infrastructures) has often been noted in reports on intermediary information seeking (Savolainen, 2006). Daland (2016) note increasing pressure on librarians to expand their knowledge on interdisciplinary sources and specialised databases. In addition, the study by Girard and Moureau (1981) on intermediary searching for chemistry literature, concluded that librarians were unable to perform effective database searches due to a lack of knowledge of the database searched, its coverage, the indexing philosophy and the entire vocabulary associated with the language of the database. Information infrastructures, including grey literature, information systems and information available through the Internet are very important (Case and Given, 2016). In addition, information fields and pathways can encompass the spectrum of information avenues an individual would consult when faced with a problem (Johnson, et al. (2006).

Makri, et al. (2008) revealed that lawyers seeking for legal information on behalf of clients, do not consult a wide range of information sources and only use information sources with which they had prior positive experiences. This is similar to findings by Kuhlthau and Tama (2001) and Schramm (1993) reporting that lawyers are selective in the information sources they use and they prefer familiar information (re)sources. Their mind set and individual qualities might also play an influence (Schramm, 1962); it is believed that humans seek information that corresponds with their prior knowledge, opinions and beliefs and avoid exposure to information that conflicts with their internal state (Case and Given, 2016).

From an information science perspective the concepts of information landscapes, information horizons and information pathways have also been introduced along with information ecology, information environment, information fields and information horizon to emphasise the scope and diversity of information resources that should be explored to fulfill information needs (Savolainen, 2006; Johnston, 2010; Choo, 2015). These are related to spatial factors that can impact on information seeking practices. For professionals the information fields and pathways might be very rich, including access to sophisticated databases, satellite systems and complex information systems (Sonnenwald, 2016). Non-professionals might however have a narrow information field, which becomes a barrier to comprehensive information access.

Competitive intelligence professionals should be mindful of information infrastructures relevant to each information or intelligence need for which they are required to seek information. An improved awareness of the available information resource also plays a pivotal role in accessing relevant information.

Cognitive frames of reference and ability to evaluate information

A study by Wathen and Roma (2005) revealed that intermediaries seeking health information on behalf of a family member have difficulties applying and processing the information they obtained to solve a problem at hand. This is in line with the work of Dervin (1999), Savolainen (2006) and Thomas, et al. (1993) on sense making. Klein (2015) argues that making sense of decisions involves finding data that fit into a frame while simultaneously looking for a frame that suits that data. If this does not happen, data might be rejected. A study by Luo and Park (2013) for example found that common challenges faced by librarians was that much of the medical information was published at a professional level, and it was difficult for them determine the appropriateness of such information for the people on whose behalf they were seeking information. Competitive intelligence professionals should be able to understand, interpret and analyse the collected information in order to provide meaningful insights to senior management.

Figure 1: Challenges of intermediary information seeking from interdisciplinary contexts (Maungwa and Fourie, 2020)

Discussion

The findings form the thematic analysis shed light on the core challenges of intermediary information seeking noted in library and information science, health sciences and law. One of the prominent findings is the lack of a systematised methodology to enable people to recognise and articulate their information needs (Savolainen, 2007; Case and Given, 2016). This points to the need for context appropriate question-negotiation and interviewing and communication skills and the need to learn from other disciplines. Taylor’s (1998) work on question-negotiation and work on the Johari Window (Shenton, 2007) are good points of departure. There are many textbooks and research articles that can deepen understanding of the intricacies of information seeking processes, search strategies and search heuristics, the evaluation and selection of information and information sources, the characteristics and skills of the online searchers and their information practices, the challenges of translating information needs into search terms and the challenges of appropriate vocabulary – especially from the early days of online searching and information retrieval (Stieg and Steig, 1980; Jahoda, 1981; Harter, 1986; Schramm, 1962; Harter and Hert 1998; Fidel, et al., 2004; Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005; Case and Given, 2016). There are also many sources from library science as well as the other disciplines that can shed light on information infrastructures and information sources such as reference works (Katz, 1978; Coonin and Levine, 2013).

Our findings on information intermediary information seeking reported from different interdisciplinary contexts relate well to issues noted in studies on competitive intelligence such as by Pirttilä (1998), Maungwa and Fourie (2018), Erdelez and Ware (2001), Keiser (Nasri (2011), Strauss and Du Toit (2010), Tsitoura and Stephens (2012). These researchers highlighted issues such as insufficient competitive intelligence training, inability to produce intelligence, insufficient use of appropriate methodologies, poor communication and absence of rigorous processes and difficulties articulating client’s information needs (Wright, et al., 2002; Nasri, 2011; Herring, 1999).

Considering the challenges that have been noticed in studies on competitive intelligence and the findings from this paper, it is clear that an information behaviour study on intermediary information seeking in competitive intelligence can benefit from experiences in other contexts. Some theories in these fields might also be useful such as the theory of information horizons, theory of interpersonal communication, Shannon and Weaver communication theory and gatekeeper’s theory (Schramm, 1962; Myers, 1990).

Moving forward, competitive intelligence professionals should ask questions about systematised intermediary practices e.g., application of appropriate question negotiation techniques, expanded knowledge of information infrastructures and landscapes and competitive intelligence domain knowledge and communication that can enhance their intermediary information seeking on behalf of decision-makers.

Conclusion

Intermediary information seeking is prone to many challenges and flaws. As shown in this paper, challenges can be disaggregated into many facets of intermediary information seeking (e.g., recognition of information needs, question negotiation, search strategies and heuristics, knowledge of information infrastructures, evaluation of results and domain knowledge of the information need). Each of these justifies in-depth studies to understand the full complexity, i.e. to gain a holistic view of the challenges of intermediary information seeking. Our scoping review touches on core facets, but there certainly are more. To ensure that the process of intermediary information seeking is efficient and to minimise failure, intermediaries should consider adopting systematised techniques, methods and procedures and appropriate communication skills such as argued in training in the different disciplines: library science, information science, health sciences and law. A study on competitive intelligence professionals as intermediary information seekers might need to consider the need for such systematic approaches.

The purpose of this paper was to raise awareness of the challenges stemming from interdisciplinary contexts and experiences with intermediary information seeking. These can open opportunities for an information behaviour study of competitive intelligence officers as intermediary information seekers.

About the authors

Tumelo Maungwa is a Lecturer in the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria. He holds a master’s degree in Information Science from the University of Pretoria and is currently a doctoral candidate. The title of his doctoral thesis is, Challenges of intermediary information seeking on competitive intelligence. He also reviews on an ad hoc basis for journals such as Mousaion, Journal of Information Management and South African Journal of Library and Information Science. Postal address: Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria, Private bag X20, Hatfield, 0028, Pretoria, South Africa. He can be contacted at tumelo.sebata@up.ac.za

Dr Ina Fourie is a Full Professor and Head of the Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria. She holds a doctorate in Information Science, and a post-graduate diploma in tertiary education. Her research focus includes information behaviour, information literacy, information services, current awareness services and distance education. Currently she mostly focuses on affect and emotion and palliative care including work on cancer, pain and autoethnography. Postal address: Department of Information Science, University of Pretoria, Private bag X20, Hatfield, 0028, Pretoria, South Africa. She can be contacted at ina.fourie@up.ac.za

References

- Abrahamson, J.A., Fisher, K.E., Turner, A.G., Durrance, J.C. & Turner, T.C. (2008). Lay information mediary behavior uncovered exploring how nonprofessionals seek health information for themselves and others online. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 96(4), 310-323. http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.96.4.006

- Addison, J., Glover, S.W. & Thornton, C. (2010). The impact of information skills training on independent literature searching activity and requests for mediated literature searches. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 27(3), 191-197.

- Alhojailan, M.I. (2012). Thematic analysis: a critical review of its process and evaluation. West East Journal of Social Sciences, 1(1), 39-47.

- Allcock, J.C. (2000). Helping public library patrons find medical information - the reference interview. Public Library Quarterly, 18(3-4), 21-27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J118v18n03_04

- Allen, D. (1998). Information technology and transformational change in the HE Sector. Library and Information Research News, 22(71), 40-51.

- Allen, D., Given, L.M., Burnett, G. & Karanasios, S. (2019). Information behavior and information practices: a special issue for research on people's engagement with technology. Journal of the Association for Information Science & Technology, 70(12), 1299-1301. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24303

- Asan, O. & Montague, E. (2014). Using video-based observation research methods in primary care health encounters to evaluate complex interactions. Informatics in Primary Care, 21(4), 161-170.

- Baird, L.L. (1978). Baird, a survey of the relevance of legal train. Legal education, 264(1), 273-286.

- Balazs, S. (1983). Az informaciok kozvetitoi (Utkereses vagy az informacios spektrum bovalese?). Intermediaries in information transfer (Seeking ways or increasing the information spectrum?). Konyvtari Figyelo, 29(4), 25. (Abstract in English was consulted).

- Bartes, F. (2015). Defining a basis for the new concept of competitive intelligence. ACTA Universitatis Agriculturae ET Silviculturae. Mendelianae Brunensis, 62(6), 1233-1242. (Abstract in English was consulted). http://dx.doi.org/10.11118/actaun201462061233

- Barton, D., Hamilton, M. & IvaniÚc, R. (Eds.). (2000). Situated literacies. Routledge Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203984963

- Bates, M.E. (2019). The new value equation. Online Searcher, 43(4), 64-77.

- Bates, M.J. (1989). The design of browsing and berrypicking techniques for the online search interface. Online review, 13(5), 407-424. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/eb024320

- Beautyman, W. & Shenton, A.K. (2009). When does an academic information need stimulate a school-inspired information want? Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 41(2), 67-80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000609102821

- Behrens, S.J. (2000). Bibliographic control and information sources (3rd. ed.). University of South Africa.

- Belkin, N.J. (1994). The use of multiple information problem representations for information retrieval. Learned Information, Inc.

- Bergeron, P. & Hiller, C.A. (2002). Competitive intelligence. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 36(1), 353-390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/aris.1440360109

- Blenkhorn, D.L. & Fleisher, C.S. (2001). Managing frontiers in competitive intelligence. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Bose, R. (2008). Competitive intelligence process and tools for intelligence analysis. Industrial management & data systems, 108(4), 510-528. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02635570810868362

- Brandt, C. & Kracht, M. (2011). Syntax, semantics and pragmatics in communication. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Semantic Systems (pp. 195-202). ACM Digital Library. https://doi.org/10.1145/2063518.2063549

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brettle, A., Hulme, C. & Ormandy, P. (2006). The costs and effectiveness of information-skills training and mediated searching: quantitative results from the EMPIRIC project. Health information and libraries journal, 23(4), 239-247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2006.00670.x

- Brown, S.W. (2008). The reference interview: theories and practice. Library Philosophy & Practice, 1-8.

- Buchanan, S., Jardine, C. & Ruthven, I. (2019). Information behaviors in disadvantaged and dependent circumstances and the role of information intermediaries. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 70(2), 117-129. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.24110

- Burke, C. (2007). History of information science. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 41(1), 3-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/aris.2007.1440410108

- Burnham, J.F. & Perry, M. (1996). Promotion of health information access via Grateful Med and Loansome Doc: why is’nt it working? Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 84(4), 498-506.

- Cairns, V.A., Reid, G.S. & Murray, C. (2015). Family members' experience of seeking help for first‐episode psychosis on behalf of a loved one: a meta‐synthesis of qualitative research. Early intervention in psychiatry, 9(3), 185-199. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/eip.12157

- Calof, J.L., Richards, G. & Smith, J. (2015). Foresight, competitive intelligence and business analytics - tools for making industrial programmes more efficient. Foresight-Russia, 9(1), 68-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.17323/1995-459X.2015.1.68.81

- Calof, J.L. & Skinner, B. (1998). Competitive intelligence for government officers: a brave new world. Optimum, 28(2), 38-42.

- Calof, J.L. & Wright, S. (2008). Competitive intelligence: a practitioner, academic and interdisciplinary perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 42(7-8), 717-730. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03090560810877114

- Carr, M.M. (2003). Super searchers on competitive intelligence: the online and offline secrets of top CI researchers. CyberAge Books.

- Case, D.O., Borgman, C.L. & Meadow, C.T. (1986). End-user information-seeking in the energy field: implications for end-user access to DOE/RECON databases. Information Processing & Management, 22(4), 299-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0306-4573(86)90028-2

- Case, D.O. & Given, L. (2016). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior (4th. ed.). Emerald Group Publishing.

- Chen, H. & Dhar, V. (1991). Cognitive process as a basis for intelligent retrieval system design. Information Processing and Management, 27(5), 405-432.

- Choo, C.W. (2015). The inquiring organisation: how organisations acquire knowledge and seek for information. Oxford University Press.

- Clarke, V. & Braun, V. (2013). Teaching thematic analysis: overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. The Psychologist, 26(2), 120-123.

- Cole, C. (2011). A theory of information need for information retrieval that connects information to knowledge. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(7), 1216-1231. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.21541

- Coonin, B. & Levine, C. (2013). Reference interviews: getting things right. The Reference Librarian, 54(1), 73-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2013.735578

- Daland, H. (2016). Managing knowledge in academic libraries. Are we? Should we? LIBER Quarterly, 26(1), 28-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.18352/lq.10154

- Dervin, B. (1999). On studying information seeking methodologically: the implications of connecting metatheory to method. Information Processing and Management, 35(6), 727-750. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(99)00023-0

- Dewdney, P. & Gillian, M. (1996). Oranges and peaches: understanding communication accidents in the reference interview. RQ, 35(4), 520-536.

- Dishman, P.L. & Calof, J.L. (2008). Competitive intelligence: a multiphasic precedent to marketing strategy. European Journal of Marketing, 42(7-8), 766-785. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03090560810877141

- Dorner, D.G., Gorman, G.E. & Calvert, P.J. (2015). Information needs analysis: principles and practice in information organizations. Facet Publishing.

- Durrance, J. C., & Fisher-Pettigrew, K. E. (2002). Toward developing measures of the impact of library and information services. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 43-53. https://doi.org/10.4018/jdsst.2010040105

- Du Toit, A.S.A. (2007). Level of importance attached to competitive intelligence at a mass import retail organization. South African Journal of Information Management, 9(4), 1-19.

- Du Toit, A.S.A. (2015). Competitive intelligence research: an investigation of trends in the literature. Journal of Intelligence Studies in Business, 5(2), 14-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.37380/jisib.v5i2.127

- Dzienkowski, J.S. (1996). Lawyering in a hybrid adversary system. William. & Mary Law. Review, 38(1), 45-50.

- Eberle, M.L. (2005). Librarians' perceptions of the reference interview. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 5(3), 29-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J186v05n03_03

- Elliott, M. & Kling, R. (1997). Organizational usability of digital libraries: case study in legal research in civil and criminal courts. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 48(11), 1023-1035. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(199711)48:11<1023::AID-ASI5>3.0.CO;2-Y

- Erdelez, S. & Ware, N. (2001). Finding competitive intelligence on internet start-up companies: a study of secondary resource use and information-seeking processes. Information Research, 7(1), paper 115. http://www.informationr.net/ir/7-1/paper115.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200717102940/http://informationr.net/ir/7-1/paper115.html)

- Fambasayi, R. & Koraan, R. (2018). Intermediaries and the international obligation to protect child witnesses in South Africa. Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal, 21(1), 10-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1727-3781/2018/v21i0a2971

- Feliciano, M.S. (1984). Legal information sources, services and needs of lawyers. Journal of Philippine Librarianship, 8(12), 71-92.

- Fidel, R., Pejtersen, A.M., Cleal, B. & Bruce, H. (2004). A multidimensional approach to the study of human-information interaction: a case study of collaborative information retrieval. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 55(11), 939-953. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.20041

- Forrest, M. & Robb, M. (2000). The information needs of doctors-in-training: case study from the Cairns Library, University of Oxford. Health Libraries Review, 17(3), 129-135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2532.2000.00285.x

- Forsetlund, L. & Bjørndal, A. (2001). The potential for research-based information in public health: identifying unrecognised information needs. BMC Public Health, 1(1), 1-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-1-1

- Fourie, I. (1999). Should we take disintermediation seriously? The Electronic Library, 17(1), 9-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02640479910329400

- Fourie, I. (2008). Information needs and information behaviour of patients and their family members in a cancer palliative care setting: an exploratory study of an existential context from different perspectives. Information Research, 13(4), paper 360. http://www.informationr.net/ir/13-4/paper360.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190810140556/http://www.informationr.net/ir//13-4/paper360.html)

- Fourie, I. & Julien, H. (2014). Ending the dance: a research agenda for affect and emotion in studies of information behaviour. Information Research, 19(4), papers108-124. http://informationr.net/ir/19-4/isic/isic09.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20191227031347/http://informationr.net/ir/19-4/isic/isic09.html#.XwmfR0l7nIU)

- Fox, S. & Duggan, M. (2013). Health online. Health, 1(1), 1-55.

- Freeman, H.E., Lipsey, M.W. & Rossi, P.H. (2005). Evaluation: a systematic approach. Library and Information Science Research, 27(1), 133-135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2004.09.009

- Frion, P. & Yzquierdo-Hombrecher, J. (2009). How to implement competitive intelligence in SMEs? Paper presented at Visio 2009, VitoriaGasteiz, Spain, 4 &5 June.

- Garcia-Alsina, M., Ortoll, E. & Cobarsí-Morales, J. (2013). Enabler and inhibitor factors influencing competitive intelligence practices. Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux Proceedings, 65(3), 262-288. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00012531311330647

- Girard, A. & Moureau, M. (1981). An examination of the role of the intermediary in the online searching of chemical literature. Online Review, 5(3), 217-225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/eb024060

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K.M. & Namey, E.E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Sage Publications. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483384436.n1

- Hanson, M. (2004). The reference interview: an anecdotal episode. Community & Junior College Libraries, 12(4), 9-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J107v12n04_04

- Harmeyer, D. (2010). A reference interview in 2025. Reference Librarian, 51(3), 248-254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02763871003792063

- Harter, S.P. (1986). Online information retrieval. Academic Press.

- Harter, S.P. & Hert, C.A. (1998). Evaluation of information retrieval systems: approaches, issues, and methods. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 32(1), 3-94.

- Herring, J.P. (1999). Key intelligence topics: a process to identify and define intelligence needs. Competitive Intelligence Review, 10(2), 4-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6386(199932)10:2%3C4::AID-CIR3%3E3.0.CO;2-C

- Hussien, F.R.M. & Mokhtar, W. (2018). The effectiveness of reference services and users’ satisfaction in the Academic Library. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development,7(3), 327-337.

- Ingwersen, P. & Ingwersen, P. (2012). Interactive information seeking, behaviour and retrieval. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 63(10), 2122-2125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.22718

- Ingwersen, P. & Järvelin, K. (2005). The turn: integration of information seeking and retrieval in context. Springer.

- Isenstein, L.J. (1992). Get your reference staff on the STAR (system training for accurate reference) track. Reference interview training at Baltimore County Public Library, 117(18), 34-37.

- Jahoda, M. (1981). Work, employment, and unemployment: values, theories, and approaches in social research. American Psychologist, 36, 184-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.2.184

- Jennerich, E.Z. & Jennerich, E.J. (1997). The reference interview as a creative art (2nd ed.). Libraries Unlimited.

- Jensen, M.A. (2012). Intelligence failures: what are they really and what do we do about them? Intelligence and National Security, 27(2), 261-282. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2012.661646

- Jin, T. & Bouthillier, F. (2008). Information behavior of competitive intelligence professionals: a convergence approach. Proceedings of the 36th annual conference of the Canadian Association for Information Science (CAIS) (pp. 5-7). http://dx.doi.org/10.29173/cais116

- Jin, T. & Ju, B. (2014). The corporate information agency: do competitive intelligence practitioners utilize it? Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(3), 589-608. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.22993

- Jinkook, L. & Jinsook, C. (2005). Consumers’ use of information intermediaries and the impact on their information search behavior in the financial market. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 39(1), 95-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2005.00005.x

- Johnson, J.D. & Case, D.O. (2012). Health information seeking. Peter Lang.

- Johnson, J.D., Case, D.O., Andrews, J., Allard, S.L. & Johnson, N.E. (2006). Fields and pathways: contrasting or complementary views of information seeking. Information Processing & Management, 42(2), 569-582.

- Johnston, S.H. (2010). From reference interview to project proposal: defining client needs to ensure research success. Part of special section Adding value. Independent information professionals, 37(1), 51-52.

- Jokic, M. (1997). Analysis of users' searches of CD-ROM databases in the National and University Library in Zagreb. Information Processing and Management, 33(6), 785-802. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(97)00039-3

- Katz, E. (1978). Looking for trouble. Journal of Communication, 28(2), 90-95. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1978.tb01602.x

- Keenan, S., Hargreaves, P., Vickery, A. & Brooks, H. (1980). A profile of the online intermediary. Fourth International Online Information Meeting, London (pp. 9-11).

- Keiser, B.E. (2016). How information literate are you? A self-assessment by students enrolled in a competitive intelligence elective. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 21(3/4), 210-228. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963568.2016.1226613

- Klein, G. (2015). A naturalistic decision making perspective on studying intuitive decision making. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 4(3), 164-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2015.07.001

- Kuhlthau, C.C., Spink, A. & Cool, C. (1992). Exploration into stages in the retrieval in the information search process in online information retrieval: communication between users and intermediaries. In D. Shaw (Ed.), Proceedings of the 5th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Information Science, Pittsburgh, 26-29 Oct 92, Medford, New Jersey (pp. 67-71). Learned Information Inc.

- Kuhlthau, C.C. & Tama, S.L. (2001). Information search process of lawyers: a call for just for me information services. Journal of Documentation, 57(1), 25-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007076

- Lanham, M.D. (2009). The behaviour/practice debate: a discussion prompted by Tom Wilson’s review of Reijo Savolainen’s everyday information practices: a social phenomenological perspective. Information Research, 14(2), paper 403. http://informationr.net/ir/14-2/paper403.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200721052051/http://informationr.net/ir/14-2/paper403.html)

- Lawless, J., Toronto, C.E. & Grammatica, G.L. (2016). Health literacy and information literacy: a concept comparison. Reference Services Review, 44(2), 144-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/RSR-02-2016-0013

- Lichstein, P.R. (1990). The medical interview. In H.K. Walker, W.D. Hall & J.W. Hurst (Eds.), Clinical methods: the history, physical, and laboratory examinations (3rd. ed.) (Chapter 3). Butterworths. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK349/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200807065420/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK349/)

- Luo, L. & Park, V.T. (2013). Preparing public librarians for consumer health information service: a nationwide study. Library & Information Science Research, 35(4), 310-317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2013.06.002

- Makri, S., Blandford, A. & Cox, A.L. (2008). Using information behaviors to evaluate the functionality and usability of electronic resources: from Ellis's model to evaluation. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(14), 2244-2267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.20927

- Maritz, R. & Du Toit, A. (2018). The practice turn within strategy: competitive intelligence as integrating practice. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 21(1), 1-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v21i1.2059

- Maungwa, T. (2017). Competitive intelligence failures from the perspective of information behaviour. (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Pretoria, Pretoria, RSA.

- Maungwa, T. & Fourie, I. (2018). Exploring and understanding the causes of competitive intelligence failures: an information behaviour lens. Information Research, 23(4). http://www.informationr.net/ir/23-4/isic2018/isic1813.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200717215625/http://informationr.net/ir/23-4/isic2018/isic1813.html)

- Maxfield, D.K. (1954). Counselor librarianship: a new departure. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/3984/gslisoccasionalpv00000i00038_ocr.txt (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200724103702/https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/3984/gslisoccasionalpv00000i00038_ocr.txt)

- McGonagle, J.J. & Vella, C.M. (2002). Bottom line competitive intelligence. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- McKenzie, P.J.A. (2003). A model of information practices in accounts of everyday-life information seeking. Journal of Documentation, 59(1), 19-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00220410310457993

- Moureau, M. (1981). Examination of the role of the intermediary in the online searching of chemical literature. Online Review, 5(1), 217-225.

- Muller, M.L. (2002). Managing competitive intelligence. Knowres Publishing.

- Murphy, C. (2006). Competitive intelligence: what corporate documents can tell you. Business information review, 23(1), 35-42. http://dx.doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n23p608

- Myers, G. (1990). Use of the information gatekeeper as an adjunct to CAI in the training of database end users in a dichotomous information society. Learned Information, Inc.

- Nasri, W. (2011). Competitive intelligence in Tunisian companies. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 24(1), 53-67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17410391111097429

- Nenzhelele, T.E. (2015). Competitive intelligence awareness in the South African property sector. Journal of Governance and Regulation, 4(4), 581-589. http://dx.doi.org/10.22495/jgr_v4_i4_c5_p2

- Nicholas, D. & Herman, E. (2010). Assessing information needs in the age of the digital consumer. Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203855799

- Nowell, L.S., Norris, J.M., White, D.E. & Moules, N.J. (2017). Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1609406917733847. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- O’Leary, M.A. & Cooper, M.W. (1981). Research needs of outstate Michigan lawyers. Michigan Bar Journal, 60(1), 640-645.

- Olsson, M. (2016). Making sense of the past: the embodied information practices of field archaeologists. Journal of Information Science, 42(3), 410-419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551515621839

- Ormandy, P. (2011). Defining information need in health-assimilating complex theories derived from information science. Health expectations, 14(1), 92-104. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00598.x

- Parker, S.E. (1989). Reference corporate law locator 1988. Library Journal, 1(144), 2-61.

- Pirttilä, A. (1998). Organising competitive intelligence activities in a corporate organisation. Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux Proceedings, 4(50), 79-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/eb051487

- Prakasan, P.M. (2013). Information needs and use of healthcare professionals: international perspective. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology, 33(6), 145-178.

- Quint, B. (2016). Resurrecting the reference interview. Online Searcher, 40(2), 33-34.

- Ramos-Eclevia, M.S. (2012). The reference librarian is now online!: Understanding librarians’ perceptions of quality chat reference using critical incident technique. Journal of Philippine Librarianship, 32(1), 13-38.

- Reynolds, S. (1994). Legal research and information needs of practitioners. Australian Law Librarian, 2(3), 134-137.

- Ronan, J. (2003). The reference interview online. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 43(1), 43-47.

- Salguero, G.C., Gámez, M.Á.F., Fernández, I.A. & Palomo, D.R. (2019). Competitive intelligence and sustainable competitive advantage in the hotel industry. Sustainability, 11(6), 1-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/su11061597

- Saunders, L. (2016). Teaching the reference interview through practice-based assignments. Reference Services Review, 44(3), 390-410. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/RSR-04-2016-0025

- Saunders, L. & Jordan, M. (2013). Significantly different? Reference services competencies in public and academic libraries. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 52(3), 216-223.

- Savolainen, R. (2006). Spatial factors as contextual qualifiers of information seeking. Information Research, 11(4), paper261. http://Informationr.net/ir/11-4/paper261.html. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20190811150126/http://informationr.net/ir/11-4/paper261.html)

- Savolainen, R. (2007). Information source horizons and source preferences of environmental activists: a social phenomenological approach. Journal of the American Society for Information Science & Technology, 58(12), 1709-1719. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/asi.20644

- Savolainen, R. (2010). Source preference criteria in the context of everyday projects: relevance judgments made by prospective home buyers. Journal of Documentation, 66(1), 70-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00220411011016371

- Schilderman, T. (2002). Strengthening the knowledge and information systems of the urban poor. Society for Information Science and Technology, 59(14), 2244-2267.

- Schoenfield, M.K. & Schoenfield, B.P. (1977). Interviewing and counselling clients in a legal setting. Akron Law Review, 11(1), 313-315.

- Schöpfel, J. & Farace, D.J. (2009). Grey literature. In Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences (pp. 2029-2039). CRC Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1081/E-ELIS3-120043732

- Schramm, W. (1962). Mass communication. Annual Review of Psychology, 13(1), 251-284. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.13.020162.001343

- Shannon, C.E. & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. University of Illinois Press.

- Shenton, A.K. (2007). Viewing information needs through a Johari window. Reference Services Review, 35(3), 487-496. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907320710774337

- Sherr, A. (1986). Lawyers and clients: the first meeting. The Modern Law Review, 49(3), 323-357. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2230.1986.tb01692.x

- Smith, L.F. (2008). Was it good for you too? Conversation analysis of two interviews. Kentucky Law Journal, 96(4), 6-22.

- Sonnenwald, D.H. (1999). Evolving perspectives of human information behaviour: contexts, situations, social networks and information horizons. In T.D. Wilson & D. Allen (Eds.), Exploring the contexts of information behaviour. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Research in Information Needs, Seeking and Use in Different Contexts, 13-15 August 1998, Sheffield, UK (pp. 176-190). Taylor Graham.

- Sonnenwald, D.H. (Ed.). (2016). Theory development in the information sciences. University of Texas Press.

- Stieg, M. & Steig, M.F. (1980). In defense of problems: the classical method of teaching reference. Journal of Education for Librarianship, 20(3), 171-183. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/40322638

- Strauss, A.C. & Du Toit, A.S.A. (2010). Competitive intelligence skills needed to enhance South Africa's competitiveness. Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux Proceedings, 62(3), 302-320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00012531011046925

- Sutton, H. (1988). Competitive intelligence (Conference Board Research Report 913). The Conference Board, Inc.

- Tabak, E. (2014). Jumping between context and users: a difficulty in tracing information practices. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(11), 2223-2232. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23116

- Tao, Q. & Prescott, J.E. (2000). China: competitive intelligence practices in an emerging market environment. Competitive Intelligence Review, 11(4), 65-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1520-6386(200034)11:4%3C65::AID-CIR10%3E3.0.CO;2-N

- Tatatabai, D. & Shore, B.M. (2005). How experts and novices search the Web. Library & Information Science Research, 27(2), 222-248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2005.01.005

- Taylor, R. (1998). Annual review article 1997. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 36(2), 293-311. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-8543.00093