Exploring temporal variations of depression-related health information behaviour in a discussion forum: the case of Suomi24

Jonas Tana, Emil Eirola, and Kristina Eriksson-Backa

Introduction. This study presents temporal variations of depression-related health information behaviour in a discussion forum. The dimension of time has previously been overlooked within health information behaviour research, and information science in general. Adding this dimension, we propose, can reveal interesting insights.

Method. The open data of the discussion forum of Suomi24, the largest and most popular discussion forum in Finland, was utilized to analyse the time stamps of all messages in the depression subcategory.

Analysis. All 116,781 messages within the depression sub-category, ranging from 1.1.2001 to 14.5.2015, were processed in JSON format, and analysed using Python. A quantitative analysis and comparison to all other messages, as well as messages in the health category was conducted.

Results. Messages posted in the depression subcategory of the Suomi24 discussion forum follow clear and recurring temporal patterns. Significant peaks are visible on different timescales, during the night time, on Monday and Thursday, as well as in spring and autumn. These results are compared to previous research on the dimension of time in relation to depression as well as information science.

Conclusion. Adding the dimension of time can reveal interesting new insights on health information behaviour, especially for stigmatised health issues like depression. Knowledge of the temporal nature of depression-related behaviour can aid early intervention, which can be beneficial for positive health outcomes.

Introduction

Modern healthcare is reliant on self-care and the role of the individual in the management of illness and health problems. Research suggests that between seventy and ninety per cent of all health problems are solved or managed without the involvement of healthcare professionals (Oliphant, 2010; Siepmann, 2008). A majority of people also try to treat or diagnose themselves before seeking medical advice from professionals (Oliphant, 2010; Siepmann, 2008). As more and more people take greater responsibility for maintaining their health, laypersons are becoming expert patients with their own health projects. Health information behaviour, or how people seek, obtain, evaluate, categorise and use information related to their health is essential in maintaining good health (Ek, 2013).

The Internet has become a convenient source, providing an endless amount of information on health issues to an increasing number of consumers (Hausner et al., 2008; Kim and Oh, 2011; Lee et al., 2014; Wikgren, 2002). In Britain, 69% of the British public searched the Internet for health information in 2013 (Dutton et al., 2013), while 64% of Finns aged 16–89 years used the Internet to find health-related information in 2017 (Tilastokeskus, 2017). Younger Finns are more active users, whereas Finnish seniors prefer to rely on medical information and interpersonal communication with health personnel (Ek and Niemelä, 2010; Eriksson-Backa, 2008, 2013).

Social media sites in particular can offer users a platform for supported learning, networking with peers, family or friends, or sharing one’s problems, processes and outcomes with others in a global community (Pulman, 2009). One of the most important aspects of modern technology is that it allows individuals to access the information they need whenever they have questions or needs, not just during clinic hours (Chan et al., 2016; Gustafson et al., 1999). This is highly relevant as time, or the temporal aspects, variations, and traits that govern and regulate many aspects of life also affect many aspects of health (Ayers et al., 2014).

These health issues and threats, which might rise anytime during the day (diurnal), week or month (seasonal), have been suggested to trigger health information behaviour, especially information needs and information seeking (Lambert and Loiselle, 2007). When considered collectively, this health information behaviour reveals reoccurring trends and patterns governed by temporal variations, which would suggest that this behaviour can be triggered and influenced by time, or the variations in time. (Ayers et al., 2014). This dimension of health information behaviour can also provide valuable insights into patterns of symptoms and disease, especially for stigmatised or sensitive health topics, such as mental illnesses like depression.

For people living with depression, the Internet provides a platform for health information behaviour, and a considerable percentage of people interested in the issues of depression are seeking and sharing answers to information needs online (Hausner et al., 2008). Because of the complexity, stigma, and barriers to care that mental illness present, individuals have been shown more likely to seek information about these problems online (Ayers et al., 2014; Chan et al., 2016; Gustafson et al., 1999; Powell and Clarke, 2006).

Research also suggests that people prefer to interact and ask questions online, since members of online communities might be more knowledgeable about the condition, or have had a similar experience (Brady et al., 2016; Gustafson et al., 1999; Halder et al., 2017; Naslund et al., 2016; Walther and Boyd, 2002). This consists of everything from finding out about and treating symptoms of depression to peer-support in managing the illness, producing a complex information context of digital traces rich with temporal data. These digital traces have been defined as 'numerically produced correlations of disparate kinds of data that are generated by our practices in a media environment characterized by digitisation'. (Hepp et al., 2018, p. 440). These digital traces provide temporal clues of health information behaviour in relation to interests, causes, symptoms, advices, and cures for health issues (Ayers et al., 2014; Lambert and Loiselle, 2007). They can also be traced in near real-time with great accuracy in relation to temporal aspects, and can thus complement existing disease profiles, reveal novel insights, as well as help propose new hypotheses for health information behaviour (Ayers et al., 2014; Chew and Eysenbach, 2010; Eriksson-Backa et al., 2016; Signorini et al., 2011; Stoové and Pedrana 2014).

Despite a long-term interest in the nature of temporality, time as a dimension of information behaviour is still an under-explored topic in the research field (Savolainen, 2018; Solomon, 1997). Reasons for this may be the methodological barriers presented by traditional means of collecting data related to time, as time expressed in the information dynamics of social systems has been difficult to capture and comprehend, especially in the question of when an individual is engaged in information behaviour (Eysenbach, 2009; Solomon, 1997).

One solution to these barriers is the use of Web data, or digital traces. The utilisation of Web data can be especially useful for stigmatised diseases or other health phenomena where traditional data is insufficient or non-existent, and where individuals have been shown more likely to seek information about their problems online (Ayers et al., 2014; Eysenbach, 2009). For instance, depression-related health information seeking in Finland has shown clear and recurring patterns, ranging from diurnal to seasonal variations (Tana, 2018; Tana et al., 2018).

Similar results were found elsewhere, where studies on Twitter posts revealed diurnal and seasonal patterns in posts related to mood and depression (Chen et al., 2018; De Choudhury et al., 2013; Golder and Macy, 2011). Nimrod (2012) found an increase in the level of activity in the online depression communities during winter, from January to March. A deeper understanding of health information behaviour in relation to time could be used to help people faced with a health-related knowledge gap. This in turn can aid in early intervention, which can be beneficial for positive health outcomes (Lambert and Loiselle, 2007). The aim of this paper is to discern the temporal variations of depression-related discussions in the largest and most popular Finnish online discussion forum (Suomi24). In order to reach this aim, the following research question is answered:

Does depression related online health information behaviour within a large discussion forum show temporal variations on different time scales?

Depression

According to the World Health Organization (2017), depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide, and a major contributor to the overall global burden of disease. In Finland depression is a major public health issue and it is estimated that at least 5% of the adult population suffer from depression every year (Patana, 2014). Depression, which is considered both a symptom and an illness, differs from everyday mood changes and can become a serious health condition, especially when it is long-lasting with a moderate to severe intensity (World Health Organization, 2017). Depression has a broad spectrum, ranging from chronic to episodic depressions with mild to severe, as well as typical to atypical symptoms.

The WHO (Marcus et al., 2012, p. 6) defines depression as follows:

Depression is a common mental disorder, characterized by sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, feelings of guilt or low self-worth, disturbed sleep or appetite, feelings of tiredness and poor concentration. Moreover, depression often comes with symptoms of anxiety. These problems can become chronic or recurrent and lead to substantial impairments in an individual’s ability to take care of his or her everyday responsibilities.

Depression is also characterized by different temporal variations: diurnal, weekly and seasonal. Diurnal variations of depression and symptoms of depression are associated with early-morning or evening worsening, or afternoon slumps (Wirz-Justice, 2008). Seasonality has also been associated with levels of both anxiety and depression, with peaks varying from autumn to mid-winter to early spring (Christensen and Dowrick, 1983; Oyane et al., 2008; Stordal et al., 2008). However, both diurnal as well as seasonal variations have been shown to be somewhat irregular, and the presence and direction of these variations are decidedly inconclusive over time (Hasler, 2013; Powell and Clarke, 2006; Wirz-Justice, 2008). The difficulties in drawing conclusions on temporal variations of depression have been suggested to because of the limitations in methodology for tracking and monitoring depression and seasonality in populations (Ayers et al., 2013; Harmatz et al., 2000). One potential method for observing temporal variations of depression is monitoring the Internet. Social media platforms have previously been suggested to be an effective disease surveillance tool (Chew and Eysenbach, 2010; Signorini et al., 2011; Stoové and Pedrana 2014), also when it comes to depression (Chen et al., 2018; De Choudhury et al., 2013; Fatima et al., 2018; Islam et al., 2018)

Depression can be treated effectively, however, fewer than half of those affected receive treatment. One of the barriers to treatment is stigma. It has been suggested that many people are reluctant to seek treatment because they do not want to be labelled as mental patients and want to avoid the stigma connected with this (Aromaa et al., 2011). This has also been suggested as the reason why a majority of individuals either suffering from depression are more likely to seek and share answers to information needs online (Ayers et al., 2014; Chan et al., 2016; Gustafson et al., 1999; Hausner et al, 2008; Powell and Clarke, 2006). Therefore, knowledge about online health information behaviour related to depression has the potential to present new meaningful temporal insights into depression.

Aggregating and analysing digital traces of online health information behaviour can be seen as infodemiological research. Infodemiology is defined as ‘the science of distribution of and determinants of information in an electronic medium, specifically the Internet, or in a population with the ultimate aim to inform public health and public policy’ (Eysenbach 2011, p. 155). Infodemiology is rooted in the idea that there is a relationship between population health and information and communication patterns on the Internet.

This kind of research is promising, as several studies have demonstrated that valid trends and patterns reflecting the entire population, and even subsets of it, can be extracted from online data (Chew and Eysenbach, 2010; Nuti et al., 2014; Signorini et al., 2011; Stoové and Pedrana, 2014). It can also help health professionals and other officials to understand broader patterns of mental illness (Ayers et al., 2014).

Furthermore, Finland is an ideal country to study changes in temporal variations for depression-related behaviour because of its northern location that causes major variations in the number of hours of daylight and the temperature during all four seasons (cf. Yang et al., 2010). However, there are still rather homogeneous weather parameters throughout the whole country. In addition to this, Finland was an early adopter of social media in all age categories, and of information and communication technology, and has a high availability of Internet services. Previous research (Nimrod, 2013) has also identified the need for research on non-English-language online depression communities in order to examine cultural variations and their impact on the manifestation of depression. This study can contribute to this by providing data on the temporal variations of depression related online health information behaviour.

Internet discussion forums

Internet discussion forums can be labelled as social media, which is defined by Merriam-Webster (Social media, n.d.) as:

informationforms of electronic communication (such as Websites for social networking and microblogging) through which users create online communities to share information, ideas, personal messages, and other content (such as videos)'.

A similar definition is given by Carr and Heyes (2015, p. 52) who define social media as

Internet-based channels that allow users to opportunistically interact and selectively self-present, either in real-time or asynchronously, with both broad and narrow audiences who derive value from user-generated content and the perception of interaction with others.

Internet discussion forums date back to the early Internet newsgroups and bulletin boards but are in no way obsolete today. Online discussion forums, more specifically, can be defined as online settings in which people exchange information, opinions and support on different topics, ranging from general to specific. Savolainen (2011) also states that they can be conceptualised as virtual information grounds that serve the end result of information sharing. Forums that are health-related are no exception. In health-related forums people who are in a similar life situations seek and exchange factual information and provide emotional support to help each other (Savolainen, 2011).

Internet discussion forums usually consist of different categories, topics and subtopics, containing threads (a thread is a collection of messages like original posts, replies and comments to replies. These user-submitted messages contain the user's details and the date and time it was posted (Internet Forum, 2018). A posted question often results in multiple responses (Savolainen, 2011). There has been an impressive increase in usage and acceptance of both health-related social media and online forums, as a massive number of people are searching for information about their health problems and posting their symptoms online (Nasralah et al., 2018; Sinha et al., 2018). Finnish statistics show that in 2014, 24% of the population aged 16–89 had written in an online forum, and that this was slightly more common among men (28%) than women (20%).

Writing in discussion forums is clearly more common for the younger demographic, as over 40% within the age category 16–34, and 35% in the age category 35–44, had written messages in an online forum in 2014 (Tilastokeskus, 2017). In the UK this seems to be just as common, as 33% posted on a message board that year (Dutton et al., 2013). These numbers are somewhat in line with the usual categorisation of online forum visitors, usually divided into active users (visitors who post on forums) and lurkers (visitors who only read forum messages and do not post). It has been estimated that lurkers make up the majority, between 45% and 90% of forum visitors (Moore et al., 2017).

Discussion forums have been studied in various health-related contexts, ranging from chronic cough (Sinha et al., 2018) and health-related effects of electronic cigarettes (Hua et al., 2013) to the most common area, information on and peer support for mental health conditions (Ali et al., 2015; Johnsen et al., 2002; Kummervold et al., 2002; Nimrod 2013; Sinha et al., 2018). In fact, online forums have been shown to be one of the most frequently used internet data sources for researchers (Im and Chee, 2012)

Time as a concept in information science

Research in information science has throughout history had a strong emphasis on spatial issues, while time as a concept has been more or less overlooked. Within information science, the temporal context of information seeking, according to Savolainen (2006; 2018), has been approached in three different ways:

- time as a fundamental attribute of situation or context of information seeking,

- time as qualifier of access to information, and

- time as an indicator of the information-seeking process.

The first approaches the general time concepts surrounding life and situations therein. The second approach is treated as a constraint in the form of time pressure imposed on access to information sources. The last approach is to viewing time as a qualifier in the information seeking process (Chen and Rieh, 2009). Of these three approaches, the first one is relevant in this case (for a more comprehensive analysis on the concept of time within information science see Savolainen (2006 and 2018M.)). It touches, as Savolainen (2018) states, on Dervin’s sense-making approach, which suggests that reality is discontinuous, gap filled and changeable across time and space, and it is accessible only, and always incompletely, in context. These are specific moments in time-space, and in spatial and temporal confluences of people, settings, activities, and events. Ultimately, temporal factors become real as constitutive elements of contexts only through human practices (Savolainen 2018.). Dervin (1992) conceptualises individuals as “time-space-bound”, and individuals in their time and space need to make sense of the world.

Within sense-making, different kinds of time receive attention, and the view of time is fundamental to the theory as it allows for the possibility of conceptualising information behaviour as temporally patterned (Davies and McKenzie, 2002; Dervin, 1992). An individual identifies a need for information upon encountering a gap in his or her knowledge that prevents them from continuing the journey through time-space (Dervin, 1992). This gap in the individual’s knowledge can be filled by something that the individual calls information. However, information seeking is only one response to a gap, and sense-making can also include seeking reassurance, expressing or sharing feelings and connecting with others, in other words, information behaviour (Case, 2012). Savolainen (2018) states that time is an important contextual and situational factor of information seeking and information behaviour.

Drawing on this, time or the temporal context can also be the situational factor or context for information seeking, because when an individual seeks information is as important as what he or she seeks (Davies and McKenzie, 2002). Individuals are different at different moments in time-space, moving from past to present to future, as defined by the linear conception of time (Savolainen, 2018). Time can likewise be perceived as a cyclic phenomenon, from the perspective and recognition of repetition of behaviour, for instance behaviour related to health (Davies and McKenzie, 2002; Dervin, 1992). Savolainen (2018) points out, that if looking at a particular season or day, one could argue that they are not cyclical because they do not reoccur in a similar fashion. However, especially within health information behaviour, reoccurring trends and patterns within these temporal units (varying from hours to days to months or seasons) can occur when considered collectively, suggesting that time, or temporal traits, also influences and triggers health information seeking and needs (Ayers et al., 2014).

Time is, as previously stated, an important contextual and situational factor and regarded as highly important within information science (Savolainen, 2006; 2018). Dervin (2005) emphasizes the dimension of time-space as fundamental in research on information behaviour. Even though many information behaviour researchers have included time or temporal factors in their research, only a few have explicitly studied time (time of day, day of the week, seasons) as a context or dimension of everyday life (Chen and Rieh, 2009). All aspects of time (and space) should therefore be taken into account within research, given that information behaviour is not static or immobile. This could potentially lead to the discovery of significant contextual dimensions within health information behaviour (Chen and Rieh, 2009; Davies and McKenzie, 2002; Savolainen, 2018). By utilising digital traces to analyse temporal trends and patterns of health information seeking and needs, we begin to understand not only how, but also when, people make sense of their world or health (Solomon, 1997). And as Wilson (1999) states, one of the strengths of Dervin’s sense-making approach lies partly in its methodological consequences, as it can lead to a way of questioning that can reveal the nature of a problematic situation, in this case, the situation in time. Wilson notes that applying such questioning can lead to genuine insights that can influence information service design and delivery.

Social media provides a novel source for studying the dimension and context of time for health information behaviour. Health-related discussions in relation to time in online forums have been studied to some extent. Halder, Poddar and Kan (2017) examined temporality in relation to mental health and online forums. They studied the problem of predicting a patient’s future emotional status based on past forum posts and provided a framework meant to track a user’s linguistic changes over time. The use of negative or positive words could reveal the deterioration or improvement of emotional status over time. Paul, et al. (2016), on the other hand, studied demographic and temporal trends connected with use of drugs that could be found in an online forum. They compared these trends against data from a large epidemiological survey. Nimrod (2013) analysed some key trends in English-based online depression communities in terms of level of activity in relation to seasonal changes. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the dimensions of time in relation to health information behaviour in online mental health discussion forums in the same detailed manner as this study.

Data and methods

Suomi 24

Suomi24 is the largest, and most popular, free and anonymous discussion forum in Finland. The site had 832,000 unique visitors per week in 2015, each of whom in average spent seven minutes on the forum in one session. The total amount of page loads a week in 2015 was over seventeen million (Aller, 2016) and during the first half of 2018, Suomi24 still had a monthly reach of over two million Internet users, making it the eighth most popular Finnish Internet site (FIAM, 2018). Overall, there are over fifty-three million (53,366,704) messages posted in Suomi24 for the time period 1st January, 2001 to the 14th. May, 2015. The forum contains several different main topics such as hobbies, society, economy and health. The category of health, with two-and-a-half million messages, includes a number of subtopics like dieting, women’s and men’s health, plastic surgery, birth control, as well as mental health. The mental health subtopic, with 589,121 messages, is divided into fourteen sub-categories, of which depression is one. All main topics, categories, subtopics and sub-categories are provided by Suomi24 and its moderators, and forum users are not able to add new or edit existing categories. The depression sub-category consists of 116,781 messages, of which 15,386 are original posts, 57,682 are replies, and 43,713 are comments to replies. In general, health and its absence is one of the most common topics in Suomi24, making it a not only a unique social media data source, but also the biggest social media data set on health in Finland (Lagus et al., 2018). The whole Suomi24 discussion forum data set can be downloaded for research purposes through FinCLARIN’s Kielipankki Korp-interface. The corpus contains all the messages in the Suomi24 discussion forum from 1st January, 2001 to the 14th. May, 2015.

The messages analysed in this study have all been posted under the sub-category ‘Depression’. The messages consist of 15,386 original posts, 57,682 replies, and 43,13 comments to replies. The data consists of a total of 116,781 messages.

The data are available in JSON format, which allows for efficient processing of large data quantities through programming. Python parsing libraries were used to extract the timestamps and category information for every post. The Python Data Analysis Library 'pandas' provides the functionality to aggregate the raw data and calculate the statistics of interest. The timestamps were converted from UTC (Universal Time Coordinated) to local time in Finland to account for daylight savings time. To evaluate the statistical significance of observed differences in the distribution of posts in different categories, we used the statistical library in SciPy to conduct a chi-squared test of independence. As this results in a multiple hypothesis scenario, the p-values were corrected for multiple comparisons by the step down method using Sidak adjustments from the StatsModels library. The standard significance level of 0.05 was used for p-values after the multiple hypothesis correction.

The data analysis in this study does not include any identifying factors nor involve any intervention in the integrity of a person. Analysis only consists of time stamps for the messages, as this metadata reveals temporal variations and patterns without conducting content analysis of messages. The data itself can be seen as public data, as it is collected from the Internet, which is claimed as a freely accessible public domain. Moreover, the Suomi24 data do not belong in the private sphere of communication, and may therefore be utilized for research purposes (Savolainen, 2011). Thus no ethical concerns were present, and an institutional board review was not required.

Results

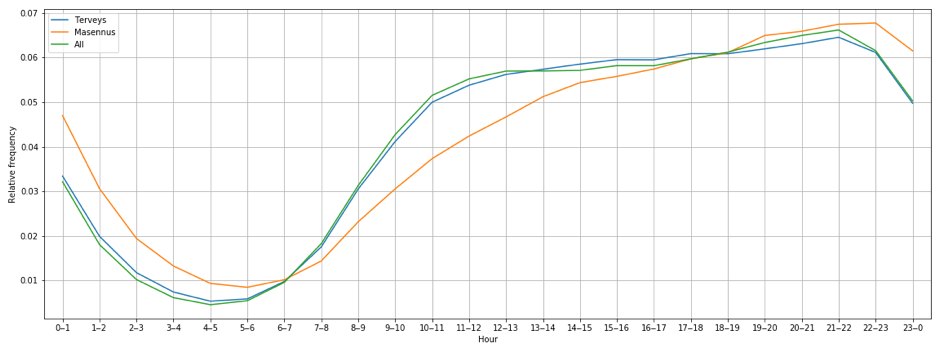

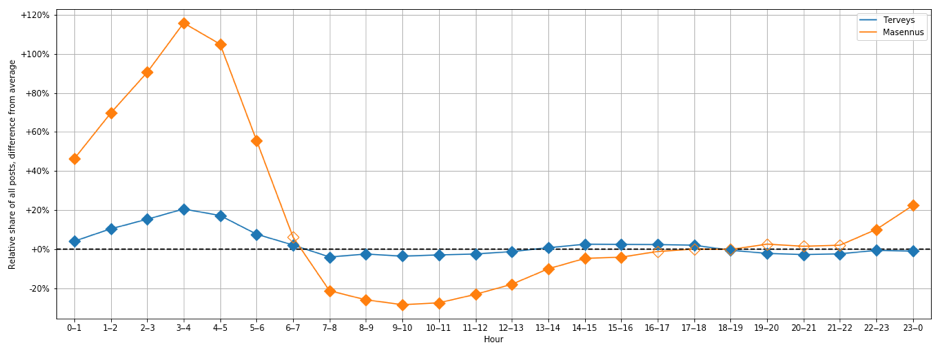

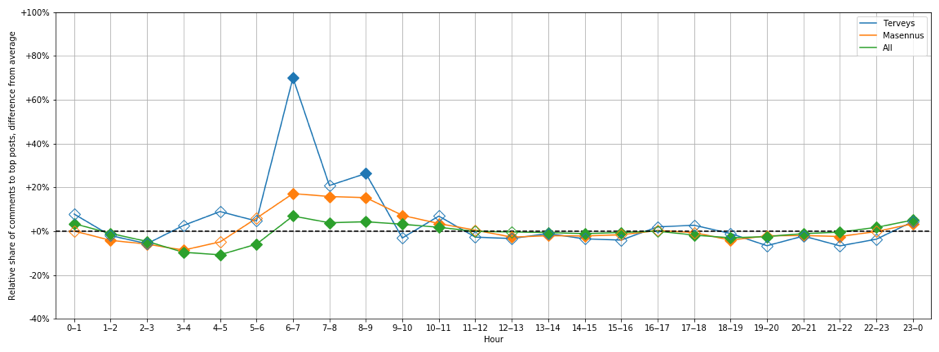

Analysing the timestamps of messages posted in the depression sub-category of the Suomi24 discussion forum shows that these messages broadly follow an hourly distribution similar to the messages in the forum as a whole. However, when compared, there are statistically significant differences in the distribution of depression-related messages, compared to the whole forum, as well as the health category. Due to the large amount of data, even small differences of ±1% are statistically significant, especially when comparing the health category to the entire forum. The comparison between the hourly distribution of all messages, the health category and the depression sub-category can be seen in Figure 1. Messages in the depression sub-category are clearly over-represented (up to +115%) during nighttime hours (between 00.00 and 05.00), and somewhat under-represented during morning and mid-day (between 07.00 and 12.00) (-30%). The health category features the same effect as the messages in the depression sub-category to a considerably weaker extent (+20% and -5%, respectively). Compared to all messages, as well as the messages in the health category, the relative number of posts in the depression sub-category clearly shows statistically significant peaks for night-time, as indicated in Figure 2.

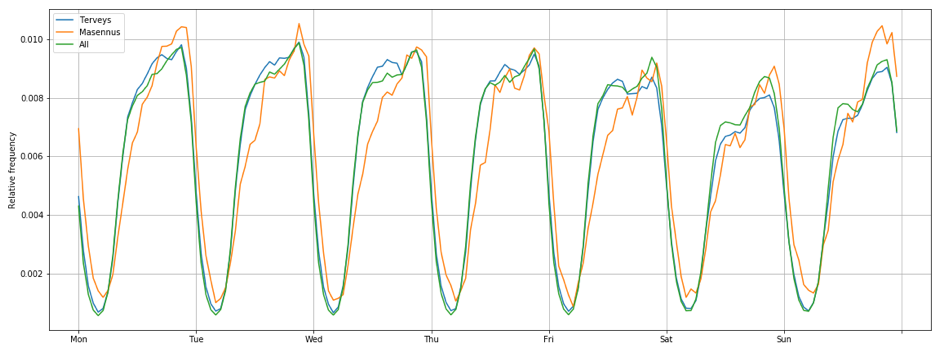

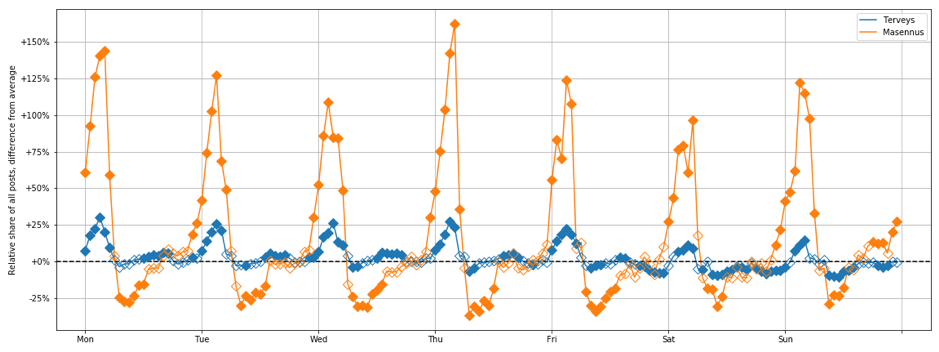

As can be seen in Figure 3, this pattern in hourly distribution of messages reiterates during every day of the week, for all messages in the health category as well as the depression sub-category. However, higher peaks are visible in the beginning of the week on Monday, and then later in the week on Thursday, a phenomenon which is especially evident for the messages in the depression sub-category. A comparison of the relative number of messages in the health category and the depression sub-category compared to all messages clearly show that depression-related messages follow recurring patterns of higher peaks and lower troughs for all weekdays, as seen in Figure 4. Figure 4 also illustrates that peaks for messages in the depression sub-category are relatively higher during night time compared to the health category, a phenomenon that is recurring for all weekdays.

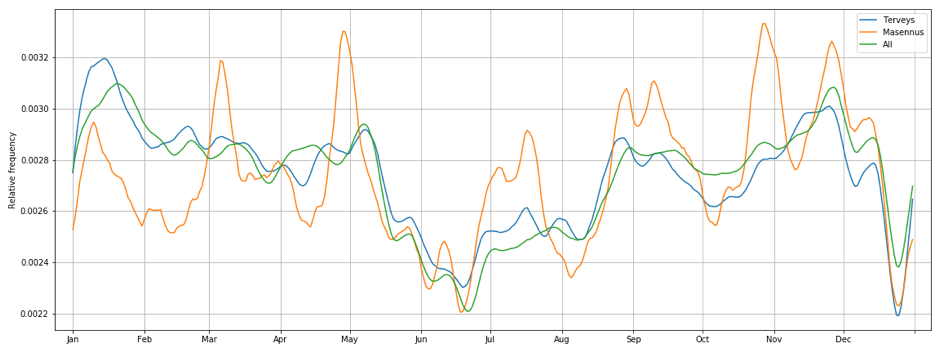

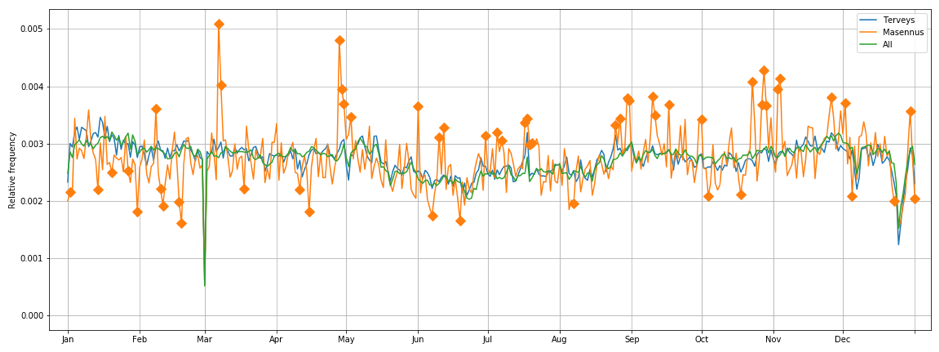

When examined on a monthly level (Figure 5), the trend of messages posted in the depression sub-category reveals a bimodal pattern that follow seasonal variations, with clear peaks in spring and autumn. As seen in Figure 5, the peaks for messages in the depression sub-category in spring and autumn are significantly higher compared to all messages, as well as the messages in the health category. The peaks are most visible in March and May, and in September, November and December. Compared to all messages and the messages in the health category, even a smaller midsummer (middle of July) peak is visible. The trough in messages in the depression sub-category in the beginning of the year, mainly January and February, clearly differs from the January peak in all messages and the messages in the health category. A closer examination of the daily amount of all messages posted in the forum, health category and depression sub-category throughout the year shows a somewhat more irregular pattern for the messages in the depression sub-category (Figure 6). It also reveals clear peak days in the depression sub-category throughout the year. The highest seasonal peaks are distributed on the following dates: the 6–7th of March, 27–29th of April, 29–30th of August, 9th of September, 22nd and 27th of October, and 2nd and 3rd of November.

Examining the depression-related messages on a thread level also reveals that replies to threads are over-represented compared to top-level posts by up to +70% during morning hours (between 06 and 08, with a clear peak at 06) as indicated in Figure 7. No similar effect can be seen for the forum as a whole.

Discussion

This study provides novel insights into how depression-related health information behaviour can be studied in relation to time. The principal findings in this study are that messages in the depression sub-category of the Suomi24 discussion forum follow clear and recurring temporal patterns, on a diurnal, weekly and seasonal scale. In relation to diurnal variations, messages are more prevalent during the evening and night. There is also evidence that depression-related health information behaviour increases on Sunday and Monday, and decreases towards Friday and Saturday. There is, furthermore, a clear bimodal pattern that suggests that depression-related health information behaviour follows seasonal variations, with peaks in spring and autumn. There are also clear peak dates during the year. These findings could support and complement previous findings on both diurnal, weekly and seasonal variations of depression.

The clear rise in the number of messages posted during evening and night within the depression sub-category compared to all other messages within the Suomi24 discussion forum supports the notion of the evening-worse diurnal mood variation that Rusting and Larsen (1998) have identified. This type of diurnal mood variation is associated with milder depressive symptoms and atypical depression, and may characterise chronic dysthymia with neurotic-type symptoms of depression, including responsivity of mood, initial insomnia, self-pity, hypochondriasis, hopelessness and anxiety (Hasler, 2013; Rusting and Larsen 1998). This finding is also in line with the diurnal patterns found for depression-related health information seeking in search engines in Finland (Tana et al., 2018). The prevalence of night-time peaks in depression have also been identified in Twitter posts by Chen et al. (2018) and De Choudhury, Counts and Horvitz (2013). The peaks during night time are in coherence with how the WHO (Marcus et al., 2012) defines depression, with symptoms of disturbed sleep as well as the assumed negative effect that depression has on sleep quality and the causal relationship between insomnia and depression (Tsuno et al., 2005). The higher response rate during early-morning could also be an indicator for disturber sleep patterns.

On a weekly level, higher message activity during Sunday and Monday support previous research that states that Sundays and Mondays (Sunday neurosis and Blue Monday are days of lower mood or depression symptoms (Akay and Martinsson, 2009; Brådvik, 2002; Tumen and Zeydanli, 2014). One interpretation for both the diurnal and weekly findings, supported by Brådvik and Rusting and Larsen (1998), is that structured versus unstructured time may account for both diurnal and weekly variations in mood and depression. Sundays as well as evening time, are for most people lower in activity and less constrained by external demands, compared to days and hours filled with work. This may trigger inner tension and negative thinking, and lead to mood disorders (Brådvik, 2002; Rusting and Larsen, 1998). De Choudhury, Counts and Horvitz (2013) give a similar explanation when they state that individuals become more prone to worrying thoughts at night due to loneliness, break from work, lack of energy, or other interactions between light and darkness and the nervous system. A similar temporal analysis of depression-related discussion forum messages have not, to the knowledge of the authors, been conducted either in Finland or anywhere else in the world, and therefore these results cannot be compared to previous research results.

Patterns of seasonal variations on depression-related health information behaviour are also visible in the depression sub-category of the Suomi24 discussion forum. There are clear peaks during autumn and spring compared both to all messages in general and in the health category. This matches the findings of Ayers et al. (2013), Tana (2018) and Yang et al. (2010), who also found clear seasonal patterns for seeking depression-related information with the help of search engines. Compared to Nimrod (2012), who studied twenty-five depression related online communities, the findings in this study are somewhat deviant, as Nimrod identified slightly higher activity during January–March. However, Nimrod’s data were limited to one year only. The seasonal findings in the present study also conform with previous conclusions of seasonality in diagnosed depression, hospital admissions and suicide rates in the Scandinavian countries and the Northern Hemisphere that have shown peaks during spring and autumn (Christensen and Dowrick, 1983; Hakko et al., 1998; Stordal et al., 2008). These findings are however contrary to studies that have shown recurring seasonal peaks for depression during the midwinter months (Harmatz, 2000; Oyane et al., 2008). This contradiction could be based on methodological limitations, as these studies were based on self-report questionnaires and diagnostic interviews.

One of the strengths of this study is that it covers depression-related health information behaviour on an accurate and meticulous scale in relation to time over a period of almost fifteen years. More traditional epidemiological methods lack this kind of minute data-collection, and suffer from other data-related issues, from collection to processing. Earlier research on diurnal, weekly and seasonal variations have been based on retrospective assessment and self-rating, either during a clinical interview or in response to an item in a questionnaire (Hasler, 2013). In this respect, novel use of data sources, in this case discussion forums, presents a promising complementary, rapid and cost-effective approach to population and public health research. Compared to the expensive, time-consuming and difficult conventional techniques, such as surveys, this kind of infodemiological research can provide new insights into depression research.

Within information science, this kind of temporal analysis surpasses and answers the methodological barrier and gap to study the dimension and perspective of time for health information behaviour. This perspective, as Dervin (2005, p. 28) points out, delivers on the mandate to study time, space and movement, and allows for the possibility of conceptualising information seeking and use as temporally patterned. This again, allows for capturing the important question of when an individual is engaged in health information behaviour, or when in time-space these gaps in knowledge appear. Applying this kind of time analysis enhances the methodological aspect of the sense-making approach. It also allows researchers to study how the context of time affects the individual, or if there are repetitive or cyclical patterns and trends in knowledge gaps on a collective level, as suggested in this study.

Limitations and future research

One of the limitations of this study is that it does not analyse the textual content of messages posted in Suomi24 depression subcategory. Therefore it is not possible to know exactly why an individual has posted the message or if the individual in question is suffering, or has suffered, from depression. Hence, it is needed to be noted that the variables (messages) used in this paper does not present actual incidence. However, as earlier research on depression in Suomi24 has shown, it is reasonable to assume that the reason people seek and share depression-related information in the Suomi24 forum is because of either an information need or to share similar personal experiences about the symptom in question (Savolainen, 2011). Moreover, as this study only captures messages posted by active forum users, all online forum lurkers fall outside the scope of analysis. Most visitors to the Suomi24 online discussion forum arrive from Google searches (Lagus et al., 2016), therefore online lurkers’ behaviour could very well have been captured in previous studies on health information seeking behaviour based on Google data in Finland (Tana, 2018; Tana et al., 2018).

Furthermore, discussion forums do not offer demographic data, which limits the drawing of conclusions about larger population behaviour in general. However, as the Internet is by far the most popular channel for health information behaviour, and as more and more people are inclined to seek and share information about health related issues online, changes in health status are often reflected by changes in different patterns on the internet (Ayers et al., 2016; Eysenbach, 2011). Therefore, the analysis of Web data may reflect larger trends in populations. Further research could utilise methods of artificial intelligence, such as natural language processing, sentiment analysis or machine learning, to analyse the language or the emotional tone in messages to identify, measure and detect depression or depressive symptoms as expressed in text. This could assist in constructing early detection warning systems in social media services and social networking sites. One particularly interesting phenomena that should be examined in a more meticulous manner is the higher rate of replies for depression related messages. Applying a qualitative research approach on the replies could help shed some light on this anomaly. Moreover, utilising the unique Suomi24 dataset, information behaviour and the dimension of time could be studied for a myriad of phenomena, ranging from other health related issues to more general topics, such as hobbies or the economy.

Implications

The findings in this study could imply that Finnish people could be more in need of, and receptive to, support in relation to depression or depressive symptoms during these times. This is especially evident for the diurnal variation, where the evening-worse pattern (where symptoms worsen during the evening), is associated with milder depressive symptoms and where early intervention could be beneficial for positive health outcomes. However, all findings in this study could be utilized by public health officials to facilitate aid and optimise positive health outcomes by providing resources at the best time for intervention. This is a time when the subjects are focusing their attention on the health threat and direct their efforts to becoming more engaged and providing ways of managing depression-related complications. With these findings in mind, there should be strategies to ensure that those in need of help have an online pathway to evidence-based information and aid, such as the Finnish Mental Hub. Utilising Web data for research in different health related research areas should in no way be seen as a replacement of traditional epidemiological research, and should only function as a complement in methods. A major challenge for mental health issues is how to not only assess but also treat mental illness among individuals who do not present for treatment or cannot be reached by more traditional means. In these cases, the Internet could function as a less stigmatising, and cost-reducing, tool to help screen, support and even treat those who do not bring their problems to the attention of health professionals.

Conclusions

This paper is a novel attempt at utilising a large social media data set to investigate time and temporal variations, from hourly to weekly and seasonal patterns, in relation to depression-related health information behaviour. Adding this dimension of time to health information behaviour has implications for information, computer and health sciences, truly utilising the potential of multidisciplinary research. As time as a factor and the temporal nature of information behaviour is still an under-explored topic in information-behaviour research (Savolainen, 2018; Solomon, 1997), adding the dimension of time can entail interesting new insights into the study of health information behaviour, and information science in general. This type of data analysis could be developed further with the aim to discover how time and temporal traits affect more general health contemplations. It could also serve as a means to identify and discover interesting insights that can function as a base for further hypothesis testing. The aim of this study was to draw attention to the possibility of studying time to gain insights into temporal nature of health information behaviour in relation to depression by utilising data from the largest discussion forum in Finland. Studying online discussion forums can be beneficial, as it has been shown that peer-support in combination with therapy significantly reduces depressive symptoms (Griffiths et al., 2012). Insight into all depression-related behaviour could be useful to be able to provide the best possible support at the best possible time, and therefore, a broad understanding of health related behaviour in relation to depression and depressive symptoms is crucial. Despite its limitations, this preliminary analysis showed that analysing depression-related health messages in a discussion forum is informative, and that the benefits of this kind of an approach are various.

About the authors

Jonas Tana is a postdoctoral researcher and senior lecturer in nursing at Arcada University of Applied Sciences. He holds a bachelor’s degree from Arcada University of Applied Sciences and a master’s degree from University of Helsinki. His main research interests lie in online health information behaviour and e-health. He can be contacted

at jonas.tana@arcada.fi

Emil Eirola is an artificial intelligence scientist

at Silo.AI and is also working as Post-doctoral Research Scientist at

the Department of Business Management and Analytics at the Arcada

University of Applied Sciences in Helsinki, Finland. He received his

M.Sc. degree in Mathematics (2009) and D.Sc. degree in Information

Science (2014) from the Aalto University School of Science in

Helsinki, Finland. Primary research interests include machine learning

with incomplete data, feature selection, and mixture models, with

applications to data in the fields of finance, security, and

healthcare. He can be contacted at emil.eirola@arcada.fi

Kristina Eriksson-Backa is a University teacher and

postdoctoral researcher in Information Studies at Åbo Akademi

University, Turku, Finland. She is docent (adjunct

professor) at the same university. Her main research interests are

information about food and health in the media, health information

behaviour, especially among older adults, understanding of health

information, health communication, and e-health. She can be contacted

at kristina.eriksson-backa@abo.fi

References

Note: A link from the title is to an open access document. A link from the DOI is to the publisher's page for the document.

- Akay, A., & Martinsson, P. (2009). Sundays are blue: aren't they? the day-of-the-week effect on subjective well-being and socio-economic status. IZA Institute of Labour Economics. (IZA Discussion Paper No. 4563). https://ssrn.com/abstract=1506315 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73BENTBBJ)

- Ali, K., Farrer, L., Gulliver, A., & Griffiths, K. M. (2015). Online peer-to-peer support for young people with mental health problems: a systematic review. JMIR Mental Health, 2(2), e19. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.4418

- Aller. (2016). Suomi24 media card. https://www.aller.fi/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Suomi24-Tuotekortti-1_2016.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/7371aCjrm)

- Aromaa, E., Tolvanen, A., Tuulari, J., & Wahlbeck, K. (2011). Personal stigma and use of mental health services among people with depression in a general population in Finland. BMC Psychiatry, 11(1), article no. 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-11-52

- Ayers, J. W., Althouse, B. M., & Dredze, M. (2014). Could behavioral medicine lead the web data revolution?. JAMA, 311(14), 1399–1400. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.1505

- Ayers, J. W., Althouse, B. M., Allem, J. P., Rosenquist, J. N., & Ford, D. E. (2013). Seasonality in seeking mental health information on Google. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44(5), 520–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.012

- Ayers, J. W., Westmaas, J. L., Leas, E. C., Benton, A., Chen, Y., Dredze, M. ,& Althouse, B. M. (2016). Leveraging big data to improve health awareness campaigns: a novel evaluation of the Great American Smokeout. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 2(1), e16. https://doi.org/10.2196/publichealth.5304

- Brådvik, L. (2002). The occurrence of suicide in severe depression related to the months of the year and the days of the week. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 252(1), 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004060200005

- Brady, E., Segar, J., & Sanders, C. (2016). "You get to know the people and whether they’re talking sense or not": negotiating trust on health-related forums. Social Science & Medicine, 162, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.029

- Carr, C. T., & Hayes, R. A. (2015). Social media: defining, developing, and divining. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 23(1), 46–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2015.972282

- Case, D. (2012). Looking for information: a survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior. Emerald Group Publishing.

- Chan, J. K., Farrer, L. M., Gulliver, A., Bennett, K., & Griffiths, K. M. (2016). University students’ views on the perceived benefits and drawbacks of seeking help for mental health problems on the Internet: a qualitative study. JMIR Human Factors, 3(1), e3. https://doi.org/10.2196/humanfactors.4765

- Chen, S. Y., & Rieh, S. Y. (2009). Take your time first, time your search later: how college students perceive time in web searching. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 46(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/meet.2009.1450460253

- Chen, X., Sykora, M. D., Jackson, T. W., & Elayan, S. (2018). What about mood swings: identifying depression on Twitter with temporal measures of emotions. In WWW '18: Companion proceedings of the Web conference 2018 (pp. 1653–1660). International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee. https://doi.org/10.1145/3184558.3191624

- Chew, C., & Eysenbach, G. (2010). Pandemics in the age of Twitter: content analysis of Tweets during the 2009 H1N1 outbreak. PLOS ONE, 5(11), e14118. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0014118

- Christensen, R., & Dowrick, P. W. (1983). Myths of mid-winter depression. Community Mental Health Journal, 19(3),177–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00759551

- Davies, E., & McKenzie, P. J. (2002). Time is of the essence: social theory of time and its implications for LIS research. Paper presented at Advancing Knowledge: Expanding Horizons for Information Science, 30th annual conference of the Canadian Association for Information Science, Toronto, Ontario, 30 May-1 June, 2002. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1027&context=fimspres (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2U5iVfW).

- De Choudhury, M., Counts, S., & Horvitz, E. (2013). Social media as a measurement tool of depression in populations. In Proceedings of the 5th Annual ACM Web Science Conference (pp. 47–56). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2464464.2464480 (http://www.munmund.net/pubs/websci_13.pdf - archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/3ddq1Xs)

- Dervin, B. (1992). From the mind’s eye of the user: the sense-making qualitative-quantitative methodology. In J.D. Glazier & R.P. Powell (Eds.), Qualitative research in information management (pp. 61–84). Libraries Unlimited.

- Dervin, B. (2005). What methodology does to theory: sense-making methodology as exemplar. In K.E. Fisher, S. Erdelez & L. McKechnie (Eds.), Theories of information behavior (pp. 25–30). Information Today, Inc.

- Dutton, W., Blank, G., & Groselj, D. (2013). Cultures of the Internet: the Internet in Britain. Oxford Internet Survey2013. Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford. http://blogs.oii.ox.ac.uk/oxis/wp-content/uploads/sites/43/2014/11/OxIS-2013.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2U46ukF)

- Ek, S. (2013). Gender differences in health information behaviour: a Finnish population-based survey. Health Promotion International, 30(3), 736–745. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat063

- Ek, S., & Niemelä, R. (2010). Onko internetistä tullut suomalaisten tärkein terveystiedon lähde? Deskriptiivistä tutkimustietoa vuosilta 2001 ja 2009. Informaatiotutkimus, 29(4). https://journal.fi/inf/article/view/3856/3640 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/397HoG2)

- Eriksson-Backa, K. (2013). The role of online health information in the lives of Finns aged 65 to 79 years. International Journal of Networking and Virtual Organizations 13(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJNVO.2013.058438

- Eriksson-Backa, K. (2008). Access to health information – perceptions of barriers among elderly in a language minority. Information Research 13(4), paper 368. http://www.informationr.net/ir/13-4/paper368.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73BCgSpxQ)

- Eriksson-Backa, K., Holmberg, K., & Ek, S. (2016). Communicating diabetes and diets on Twitter-a semantic content analysis. International Journal of Networking and Virtual Organisations, 16(1), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJNVO.2016.075133

- Eysenbach, G. (2011). Infodemiology and infoveillance: tracking online health information and cyberbehavior for public health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 40(5), 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.02.006

- Eysenbach, G. (2009). Infodemiology and infoveillance: framework for an emerging set of public health informatics methods to analyze search, communication and publication behavior on the Internet. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 11(1), e11. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1157

- Fatima, I., Mukhtar, H., Ahmad, F.H., & Rajpoot, K. (2018). Analysis of user-generated content from online social communities to characterise and predict depression degree. Journal of Information Science, 44(5), 683–695. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551517740835

- FIAM (Finnish Internet Audience Measurement). (2018). Tulokset. http://fiam.fi/tulokset/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/7372Ow4Ay)

- Golder, S. A., & Macy, M. W. (2011). Diurnal and seasonal mood vary with work, sleep, and daylength across diverse cultures. Science, 333(6051), 1878–1881. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1202775

- Griffiths, K. M., Mackinnon, A. J., Crisp, D. A., Christensen, H., Bennett, K., & Farrer, L. (2012). The effectiveness of an online support group for members of the community with depression: a randomised controlled trial. PLOS ONE, 7(12), e53244. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053244

- Gustafson, D. H., Hawkins, R., Boberg, E., Pingree, S., Serlin, R. E., Graziano, F., & Chan, C. L. (1999). Impact of a patient-centered, computer-based health information/support system. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 16(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00108-1

- Hakko, H., Räsänen, P., & Tiihonen, J. (1998). Seasonal variation in suicide occurrence in Finland. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 98(2), 92–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10048.x

- Halder, K., Poddar, L., & Kan, M. Y. (2017). Modeling temporal progression of emotional status in mental health forum: a recurrent neural net approach. In Proceedings of the 8th Workshop on Computational Approaches to Subjectivity, Sentiment and Social Media Analysis, (pp. 127–135). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W17-5217.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://tinyurl.com/qrqmh8x)

- Harmatz, M. G., Well, A. D., Overtree, C. E., Kawamura, K. Y., Rosal, M., & Ockene, I. S. (2000). Seasonal variation of depression and other moods: a longitudinal approach. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 15(4), 344–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/074873000129001350

- Hasler, B. (2013). Diurnal mood variation. In M. Gellman & R.J. Turner, (Eds.). Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine (pp. 612–614). Springer-Verlag.

- Hausner, H., Hajak, G., & Spießl, H. (2008). Gender differences in help-seeking behavior on two internet forums for individuals with self-reported depression. Gender Medicine, 5(2), 181–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genm.2008.05.008

- Hepp, A., Breiter, A., & Friemel, T. N. (2018). Digital traces in context—an introduction. International Journal of Communication, 12(2018), 439–449 https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/download/8650/2247 (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://tinyurl.com/wwo92o3)

- Hua, M., Alfi, M., & Talbot, P. (2013). Health-related effects reported by electronic cigarette users in online forums. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(4).

- Im, E. O., & Chee, W. (2012). Practical guidelines for qualitative research using online forums. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 30(11), 604. https://doi.org/10.1097/NXN.0b013e318266cade

- Internet forum. (2018) In Wikipedia: the free encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_forum (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73727Sx0k)

- Islam, M. R., Kabir, M. A., Ahmed, A., Kamal, A. R. M., Wang, H., & Ulhaq, A. (2018). Depression detection from social network data using machine learning techniques. Health Information Science and Systems, 6(1), article no. 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13755-018-0046-0/li>

- Johnsen, J. A. K., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Gammon, D. (2002). Online group interaction and mental health: an analysis of three online discussion forums. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 43(5), 445–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.00313

- Kim, S. M., & Oh, J. Y. (2011). Health information acquisition online and its influence on intention to visit a medical institution offline. Information Research, 16(4), paper 505. http://www.informationr.net/ir/16-4/paper505.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73BCnG002)

- Kummervold, P. E., Gammon, D., Bergvik, S., Johnsen, J. A. K., Hasvold, T., & Rosenvinge, J. H. (2002). Social support in a wired world: use of online mental health forums in Norway. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 56(1), 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480252803945

- Lagus, K., Pantzar, M., Ruckenstein, M., & Ylisiurua, M. (2016). Suomi24: muodonantoa aineistolle. [Suomi24: format for the material.]. University of Helsinki. (Faculty of Social Sciences Publication, 10). https://bit.ly/2UpuZHX (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73BEajLDl)

- Lagus, K., Ruckenstein, M., Juvonen, A., & Rajani, C. (2018). Medicine radar: a tool for exploring online health discussions. In E. Mäkelä, M. Tolonen, & J. Tuominen, (Eds.). Proceedings of the Digital Humanities in the Nordic Countries 3rd Conference, (pp. 460-468) . CEUR-WS.org http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2084/short21.pdf (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://web.archive.org/web/20200115081022/http://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2084/short21.pdf)

- Lambert, S. D., & Loiselle, C. G. (2007). Qualitative Health Research, 17(8), 1006–1019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732307305199

- Lee, K., Hoti, K., Hughes, J. D., & Emmerton, L. (2014). Dr Google and the consumer: a qualitative study exploring the navigational needs and online health information-seeking behaviors of consumers with chronic health conditions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(12), e262. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3706

- Marcus, M., Yasamy, M. T., van Ommeren, M., Chisholm, D., & Saxena, S. (2012). Depression: a global public health concern. World Health Organization. https://tinyurl.com/k23r3zv (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6rGDQq3sF)

- Moore, D., Drey, N., & Ayers, S. (2017). Use of online forums for perinatal mental illness, stigma, and disclosure: an exploratory model. JMIR Mental Health, 4(1), e6. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.5926

- Naslund, J. A., Aschbrenner, K. A., Marsch, L. A., & Bartels, S. J. (2016). The future of mental health care: peer-to-peer support and social media. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 25(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796015001067

- Nasralah, T., Ahmed, A., Wahbeh, A., Alyami, H., & Ali, A. (2018). Negative effects of online health communities on user's health: the case of online health forums. In MWAIS Proceedings 2018, 5. Association for Information Systems. https://bit.ly/2vDCt1F (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2QvjKg7)

- Nimrod, G. (2013). Online depression communities: members’ interests and perceived benefits. Health Communication 28(5), 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2012.691068

- Nimrod, G. (2012). From knowledge to hope: online depression communities. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 11(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijdhd.2012.009

- Nuti, S. V., Wayda, B., Ranasinghe, I., Wang, S., Dreyer, R. P., Chen, S. I., & Murugiah, K. (2014). The use of Google trends in health care research: a systematic review. PLOS ONE, 9(10), e109583. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109583

- Oliphant T. (2010). The information practices of people living with depression: constructing credibility and authority. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada. http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/35 (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6rGD92Niu)

- Oyane, N. M., Bjelland, I., Pallesen, S., Holsten, F., & Bjorvatn, B. (2008). Seasonality is associated with anxiety and depression: the Hordaland health study. Journal of Affective disorders, 105(1–3), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.05.002

- Patana, P. (2014). Mental health analysis profiles: Finland. OECD Publishing. (OECD Working Papers, 72.) http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jz1591p91vg-en (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/7371tNqZb)

- Paul, M. J., Chisolm, M. S., Johnson, M. W., Vandrey, R. G., & Dredze, M. (2016). Assessing the validity of online drug forums as a source for estimating demographic and temporal trends in drug use. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 10(5), 324–330. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000238

- Powell, J., & Clarke, A. (2006). Internet information-seeking in mental health: population survey. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 189(3), 273–277. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.017319

- Pulman, A. (2009). Twitter as a tool for delivering improved quality of life for people with chronic conditions. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness, 1(3), 245–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-9824.2009.01027.x

- Rusting, C. L., & Larsen, R. J. (1998). Diurnal patterns of unpleasant mood: associations with neuroticism, depression, and anxiety. Journal of Personality, 66(1), 85–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00004

- Savolainen, R. (2018). Information seeking processes as temporal developments: comparison of stage based and cyclic approaches. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 69(6), 787–797. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24003

- Savolainen, R. (2011). Requesting and providing information in blogs and internet discussion forums. Journal of Documentation, 67(5), 863–886. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411111164718

- Savolainen, R. (2006). Time as a context of information seeking. Library & Information Science Research, 28(1), 110–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2005.11.001

- Siepmann, M. (2008). Health behavior. In W. Kirch (Ed.), Encyclopedia of public health (pp. 515–521). Springer Science & Business Media.

- Signorini, A., Segre, A. M., & Polgreen, P. M. (2011). The use of Twitter to track levels of disease activity and public concern in the US during the influenza A H1N1 pandemic. PLOS ONE, 6(5), e19467. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019467

- Sinha, A., Porter, T., & Wilson, A. (2018). The use of online health forums by patients with chronic cough: qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(1), e19. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7975.

- Social media. (n.d.). In Merriam-Webster dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/social media (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73720jkzB)

- Solomon, P. (1997). Discovering information behavior in sense making. I. Time and timing. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 48(12), 1097–1108. http://doi.org/drk33r

- Stoové, M. A., & Pedrana, A. E. (2014). Making the most of a brave new world: opportunities and considerations for using Twitter as a public health monitoring tool. Preventive Medicine, 63, 109–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.03.008

- Stordal, E., Morken, G., Mykletun, A., Neckelmann, D., & Dahl, A. A. (2008). Monthly variation in prevalence rates of comorbid depression and anxiety in the general population at 63–65 North: the HUNT study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 106(3), 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.007

- Tana, J. (2018). An infodemiological study using search engine query data to explore the temporal variations of depression in Finland. Finnish Journal of eHealth and eWelfare, 10(1), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.23996/fjhw.60778

- Tana, J. C., Kettunen, J., Eirola, E., & Paakkonen, H. (2018). Diurnal variations of depression-related health information seeking: case study in Finland using Google trends data. JMIR Mental Health, 5(2), e43. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.9152

- Tilastokeskus; Official Statistics of Finland. (2017). Väestön tieto- ja viestintätekniikan käyttö 2017. [Population information - use of communication technology 2017]. Tilastokeskus: Official Statistics of Finland. https://www.stat.fi/til/sutivi/2017/13/sutivi_2017_13_2017-11-22_fi.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73BEic3SL)

- Tsuno, N., Besset, A., & Ritchie, K. (2005). Sleep and depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66(10), 1254–1269. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v66n1008

- Tumen, S., & Zeydanli, T. (2014). Day-of-the-week effects in subjective well-being: does selectivity matter? Social indicators research, 119(1), 139–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0477-6

- Walther, J. B., & Boyd, S. (2002). Attraction to computer-mediated social support. In C.A. Lin and D. Atkin (Eds.), Communication technology and society: audience adoption and uses (pp. 153–188). Hampton Press.

- Wikgren, M. (2002). Health discussions on the Internet: a study of knowledge communication through citations. Library & Information Science Research, 23(4), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(01)00091-3

- Wilson, T. D. (1999). Models in information behaviour research. Journal of Documentation, 55(3), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007145 (https://tinyurl.com/s7vhqop)

- Wirz-Justice, A. (2008). Diurnal variation of depressive symptoms. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10(3), 337. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181887/ (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://tinyurl.com/wjjlws7)

- World Health Organization. (2017). Depression fact sheet. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/ (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/7372C0cIc)

- Yang, A. C., Huang, N. E., Peng, C. K., & Tsai, S. J. (2010). Do seasons have an influence on the incidence of depression? The use of an internet search engine query data as a proxy of human affect. PLOS ONE, 5(10), e13728. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013728