Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Ljubljana, Slovenia, June 16-19, 2019

Rethinking context in information research: bounded versus centred sets

Isto Huvila

Introduction. Context is one of the key concepts in library and information science research.

Method.This paper provides a conceptual overview of the use of the notion of usefulness in library and information science literature, explicates its relation to key parallel concepts, and on the basis of an empirical vignette in the context of health information research, discusses the potential limits and advantages of referring to usefulness instead of and together with other related concepts.

Analysis.The paper is based on conceptual discussion and a selective review of literature.

Results.This paper explicates the implications of the traditional approach of conceptualising context in information research as bounded sets or ’quasi-bounded-sets’, and to contrast an alternative view of treating them as centred sets or processes. Instead of seeing context as a single- or multi-layered surrounding, describing it as a centred set makes it a position with affinities to different factors, situations, people or things.

Conclusions.Even if all of the approaches have their inherent limitations, the notion of centred set provides means to rethink context and to help to avoid the temptation to treat it as an unspecified container and make it possible to explicate its constituents and their movement toward or from its nucleus.

Introduction

Context has turned to one of the key concepts in library and information science research especially in the wake of the increasing popularity of the social and cultural metatheories (Tabak, 2014; Tuominen et al., 2002; Talja et al., 2005) In information behaviour research, the focus of empirical work has shifted from an earlier focus on scholarly and professional contexts to embrace information practices in leisurely (Hartel et al., 2016) and everyday (Savolainen, 1995; McKenzie, 2003) contexts and further to underline the deep contextuality (Agarwal, 2017) and cross-contextuality (e.g., Huotari and Chatman, 2001; Jaeger and Burnett, 2010) and phenomenological nature (Keilty and Leazer, 2018; Gorichanaz, 2015; Savolainen, 2008a) of information interactions. It is possible to see a similar broadening of focus also in other areas of library and information science from knowledge organiz ation (e.g., Jacob, 2001; Andersen, 2017) to information searching and retrieval (e.g., Skov et al., 2008; Waller, 2011; Borlund, 2016). There are parallels in other disciplines, for instance, in archaeology where the focus of inquiry has broadened from a traditional emphasis of immediate micro-contexts of material objects to landscapes, taskscapes and phenomenology (Edgeworth, 2016; Knapp and Ashmore, 1999). In library and information science, information needs (Savolainen, 2012) and activities have been acknowledged to be, at the same time, situational and contextual in a local spatiotemporal sense, simultaneously than they have been underlined as holistic (Huvila and Ahmad, 2018) and information world (Jaeger and Burnett, 2010), or life world (Burnett and Jaeger, 2008; Habermas, 2004), wide phenomena. What remains often relatively vague is, however, how the different micro and macro-level contexts are related to each other and how they interact. Perhaps the most common approach to conceptualise contexts has been to treat them (either implicitly or explicitly) in terms of bounded (Jeffreys and Jeffreys, 1988) or ’quasi-bounded-sets’, explain their co-existence as overlap and visualise it using Venn-diagram-like illustrations. In spite of its intuitiveness, the approach has several potential issues. One obvious issue is how and where to draw the boundaries of a context and another one is that even if an overlap of bounded sets can be completely or partial, it is binary for specific parts of the context. Even if it would not be entirely appropriate to take diagrammatic visualisations or implicit conceptualisations too literally, the view of contexts as bounded set-like constructs, its implications and possible alternatives warrant closer consideration.

The aim of this paper is to explicate the implications of conceptualising context in information research as bounded sets or ’quasi-bounded-sets’, and to contrast the approach with alternative views of treating them as centred sets or processes. A centred set-based approach refers to a context as centred rather than bounded space whereas the context-as-process approach focuses on context as being continuously made rather than something that something that is. The paper argues that even if all possible approaches to illustrate and explain rather than define context have their inherent limitations, there are advantages in considering alternative ways of thinking about context and more specifically thinking about context in different ways. A closer attention to what and how a context is instead of merely framing it as a scene of informational activities is useful for framing its impact and limits in information research.

Context in library and information science scholarship

The environment within which information behaviour and practices take place have been touched upon in the library and information science literature in different ways. Various types of spatial and quasi-spatial metaphors (Acker and Uyttenhove, 2012; Savolainen, 2006a) seem to have been especially popular. These include notions like information grounds (Fisher et al., 2004), information landscapes (Lloyd et al., 2017), small worlds (Chatman, 1991), arenas and settings (Anderson, 2007), information worlds (Chatman, 1992; Burnett, 2015) and many others. More can be found in the verges of library and information science (e.g., Clarke and Star, 2008; Purves et al., 2019). Courtright (2007) argues that many of the spatial concepts have been used not only as qualifiers of specific types of contexts but as equivalents to the notion of context itself. In addition to spatial milieus, previous scholarship has identified a large number of other contextual facets, including epistemic (Choo, 2007) and information culture (Ginman, 1988; Widén-Wulff, 2000), time (Savolainen, 2006b, 2012), work role (Huvila, 2008), disciplinarity (Normore, 2011), and the type of information interacted with (Savolainen, 2008b) that influence and form a backdrop to information activities.

Among the diverse conceptualisations, Dervin identifies three different approaches to treating context. Even if Dervin’s categorisation is from mid 1990s, it has retained its usefulness in explicating the contemporary research landscape. First, often context is considered to be everything else than an actor or the phenomenon of interest (Dervin, 1997). The second approach is to see it as a whole composed of a number of different factors. The third approach is to see context as “the carrier of meaning”, a surrounding that scaffolds all human action (Dervin, 1997, p. 14). Dervin (1997) articulated further a set of themes she believed that all warrant a particular approach when addressing context from a theoretical and philosophical perspective independent of the specific metatheoretical orientation assumed. On a fundamental level, context is in the eye of the spectator. Talja and colleagues (1999, p. 761) define context as “frames of reference which allow us to choose the relevant elements for study”. Depending on how a researcher sees informational phenomena through an objectivist or interpretivist lens, context can be defined either as behavioural patterns or as phenomena, which are “mediated by social and cultural meanings and values” (Talja et al., 1999, p. 761). The two approaches do roughly correspond with Dervin’s first and third categories. However, in spite of the tendencies to dichotomise objectivist and interpretivist, and cognitive individual-focused and sociocultural scholarship, many popular approaches of library and information science scholarship reside somewhere between the extremes (Tabak, 2014). These include Dervin and her Sense-Making Methodology, domain analysis (Hjørland, 2004) and the general orientation to see actors embedded in their contexts (Courtright, 2007). As Tabak (2014) argues, there are obvious problems associated with the balancing act of trying to account both for context and what resides within it.

Considering the scope of the present study, this article is not attempting to provide a comprehensive overview how context has been approached and treated in the library and information science research. To this end, there are couple of fairly recent reviews available. Agarwal (2017) has recently reviewed context in selected models that relate to information behaviour. From a different perspective to contextuality, Tabak (2014) provides an equally useful review that traces the pre-history and emergence of context sensitive and centred library and information science scholarship. Also Johnson (2003) provides an insightful review of earlier literature on contexts as a part of his text where he points to the importance of delimiting and defining contexts when studying information seeking and its multi- and cross-contextual aspects. In addition, there are several texts that inquire into the notion of context and the implications of contextuality in information research (e.g., Chang and Lee, 2001; Saracevic, 2010; Savolainen, 2012; Thomas and Nyce, 2001). Context has been theorised also in other disciplines (e.g., Dijk, 2008), sometimes in ways that could inform library and information science research. The inherent problem with the notion is, however, that it is a slippery concept (Dourish, 2004) without a single accepted definition and that is seldom anchored in proper theorising (Agarwal, 2017). As a result, it has become fairly common to refer to such notions as “information interactions in context”, criticised by Saracevic (2010) of not making real sense, because all information interactions are contextual, that contexts are multi-layered and that they are not self-revealing or self-evident.

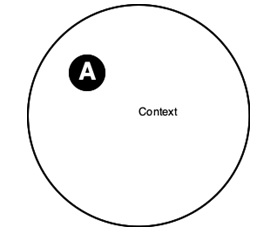

Context as a bounded set

Metatheoretical frames of reference, or the lack of theoretical grounding in much of information research (Talja et al., 1999; Agarwal, 2017) have an undeniable impact on what kind of a beast context is. In spite of the differences and whether context is perceived as a scene for information activities, a small world (Chatman, 1991) or an information ground (Pettigrew, 1999) produced as a bi-product of social interaction, the specific understanding of what and how context is remains conspicuously similar across different conceptualisations and (with some reservations) reminds of a bounded set. The notion of bounded set comes from set theory, a branch of mathematical logic and refers to a finite set consisting of bounded resources (Sazonov, 1997). In some cases when context is treated as a container of actors and information activities, the analogue is close to being a literal one. A specific either known or partially known set of patterns or factors belong to the context and the rest fall outside (a diagrammatic example in Figure 1) of it where A refers to an object of interest, for instance, the information behaviour or practices of a particular group or a specific document in a library collection. In addition to obvious cases, also many of the more elaborate and messy conceptualisations of context can be explained in terms of bounded or in practice, often semi-bounded (fuzzy) sets, which are open to partial and multiple membership. Understood as a set of specific behavioural patterns that belong to it, or as a (specific) phenomenon with a set (particular) cultural values and meanings (cf. Talja et al., 1999), a context can be explained in terms of reminding of or being a bounded set. The affinity of the conceptualisations and bounded sets is most apparent in diagrammatic visualisations of contexts (cf. e.g., the models reviewed and proposed by Agarwal, 2017). Of these can be mentioned, for instance, the models of Savolainen (1995), Sonnenwald (1999), Dervin (in Dervin and Foreman-Wernet, 2012) and McKenzie (2003). They seem to, at least to the knowledge of the author, without many exceptions, depict context as a bounded area or an externality to the studied phenomenon. Context is drawn in the models as a space that is separate from or included in the studied phenomenon. Not seldom, it is an area that surrounds (e.g., McKenzie, 2003 and Sonnenwald, 1999) or underpins the aspects that are the focus of the model (e.g., in Dervin and Foreman-Wernet, 2012) as illustrated by the colour-coded models in Agarwal’s review (Agarwal, 2017). In both cases, the set is bounded either explicitly as a subset or implicitly as the totality of everything that surrounds the object of interest.

For the sake of fairness, it is necessary to acknowledge that in most cases, the literature does not explicate in detail the links between context and that what is studied. Context is just somehow either in the background or the background to that what is being studied, and the focus is on the real object of interest. The most obvious example of this are the statements how many things, for instance, the value (e.g., Eaton and Bawden, 1991) and redundancy (Foulonneau, 2007) of information ’depends on context’ – especially when the discussion is closed by this observation and the mentioned ’context’ is not discussed in any more detail. Referring to metatheories that deny the traditional subject-object dichotomy like Actor-Network Theory (ANT) (Latour, 2005a) and make a case of mapping connections instead of dichotomising what is in and what is out, does not automatically mean that there would not be a similar invisible context behind a specific actor-network that is in the focus of the study. In some cases, as in the detailed review of Agarwal (2017), researchers distance themselves from the context-as-container approach but still visualise context in a manner that can be (mis)interpreted as a container (e.g., Agarwal, 2017, p. 104). There is also an emerging body of context-centred library and information science scholarship within which context is not a mere backdrop of action but becomes an object of inquiry (Tabak, 2014). In practice, however, in spite of the efforts to decentre actors and contexts, there is still often a ’context’, or even multiple contexts, that somehow underpin the phenomenon or the part of the network of primary interest (cf. e.g., Huizing and Cavanagh, 2011).

Rethinking context as a centred set

If the purpose of a study is to decentre context and non-context, as Tabak (2014) suggests, Actor-Network Theory (ANT) provides a useful approach to trace information activities as a circulation of individualisation and collectivisation in a rhizomatic network of human and non-human actants. The relative drawback with ANT (Latour, 2005b) and comparable decentred approaches is that they do precisely what they are supposed to do, namely, expel context and actors from the agenda as discrete notions. There are, however, legitimate reasons to be interested in context, either as perceived from the perspective of the researcher as a backdrop of the object of interest, or from the perspective of human or non-human actors, groups or, for instance, organiz ations, to understand how they themselves conceive the underpinnings of their doings. Explicating both the external (researcher) and internal (’user’) perspectives using either separate or related methods (e.g., user drawn, Sonnenwald and Wildemuth, 2001, and analytical, Huvila, 2009, information horizon maps) and theories, and especially as Huizing and Cavanagh (2011) underline, unforgetting the often ignored ’user’ perspective has irrefutable value in understanding the human space of experience (Koselleck, 2004). Putting or keeping users (or any other specific aspect of the what is happening) in the focus is not opposed to de-centred approaches (including ANT). When done mindfully, making a distinction between an object of interest and its context can be helpful in emphasising the distinct impact and peculiarities of particular aspects (i.e., the object of interest) of the totality. Meanwhile, it does not mean that context needs to be left unexplored and used as a undefined category of everything else.

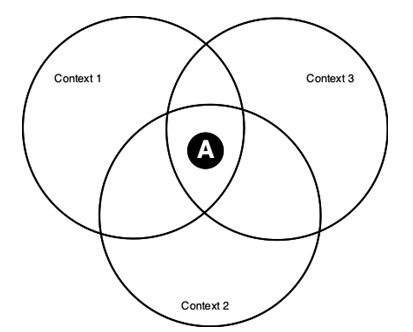

However, the conceptualisation of context as a bounded or quasi-bounded set has several shortcomings. First, it is difficult to explicate the relations between contexts and especially what happens when multiple contexts overlap. Even if their relation to mathematical sets would be completely metaphorical rather than literal, most conceptualisations do not as such provide practical means to describe the overlap of two bounded contexts in other than binary sense (i.e., there is or is not overlap). A classic example of the binary overlap of contexts is the matching of search and index terms in information retrieval commonly illustrated using Venn-diagrams. A document (A) either does or does not belong to specific context(s) of relevance – or as illustrated in Figure 2, it belongs to all known or articulated contexts. In visual models where the context is specific to a studied moment of in time-space (e.g., Savolainen, 1995; Sonnenwald, 1999; McKenzie, 2003), the question of the overlap of bounded-set-like-contexts remains even more unclear. Second, a bounded-set-like conceptualisation does not provide means to articulate the relative influence of the constituents of the contexts whether they are contextual factors, related contexts, human or non-human actors, language or something else. Context becomes easily a box of all known and unknown things that influence the object of study whether it is a set of documents, index terms, information behaviour and practices, or a library collection. In practice, this can easily lead to thinking about context literally as the box how it is depicted in some diagrammatic visualisations (e.g., the ones of Savolainen, 1995; McKenzie, 2003; Karunakaran et al., 2013), narrowing them and how they are conceived and described down, and further, to claims that contexts have no limits.

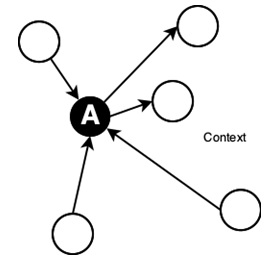

Centred sets are another type of sets in the context of set theory (Just and Weese, 1997). The concept was appropriated from mathematics to social studies and more specifically to theology by Paul Hiebert in a series of texts where he discussed whether church should be conceptualised as a bounded, centred or fuzzy set (Hiebert, 1978). Hiebert’s and his followers theological work is of secondary interest in this article but the concept, as it was appropriated and contrasted to bounded and fuzzy sets, can provide a potentially useful perspective to imagining and understanding the notion of context in library and information science. Whereas a bounded set is defined in a container-like terms as a set of things with a common attribute (at the minimum, of belonging to the set) that separates those who are in and who are out, a centred set does not have boundaries. Centred sets are defined by the relation entities (white dots in Figure 3) have to the centre of the set (A) and their movement inwards or outwards (Fig 3) at a given moment of time. When thinking about centred sets, it is important to make a distinction between a centred set and its visual representation (diagram) similarly to, how this article argues, it it important to distinguish between what a context is, its (visual) representations, and how to think about it. Instead being a network diagram, relational visualisation or knowledge graph, a centred set is a particular type of a set. In a social studies sense, the potential strength of centred sets is in how they can help to think about contexts and their aspectual facets rather than being a new entity-relation model.

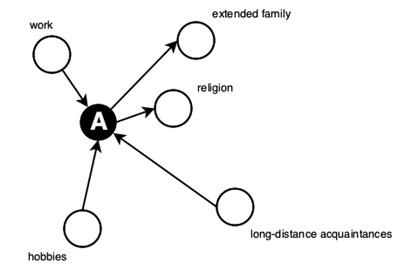

Using centred sets as a conceptual tool, or an imaginary, context opens up as a set of factors, actors, things and other contexts that have a relation to that what defines the context i.e., whose (or what) context it is (the centre). These things (white dots i.e., factors, aspects) can have different kinds and levels of affinities to the centre (A) and they may be moving closer to it, distancing from it, staying where they are, or both at a given moment in time-space – to stay where they are or move to another direction at another. This can be exemplified by looking at the recent research on work-life balance points (as illustrated in Figure 4). Even if close and weaker personal social contacts, hobbies and interests and work are a part of the context within which average adults live their everyday lives, the increasing intimacy of work (vividly described by Gregg, 2011) is changing the earlier status quo of the separation of work and leisure that was established during the industrial revolution (Broadbent, 2016). For instance, Broadbent (2016) notes that closer relations are moving closer to us whereas the significance of weaker ties is lessening at the same time when work has moved to become an increasingly intimate part of everyday life. Information researchers have made similar observations of the changing contexts of information work (e.g., Huvila, 2013, 2016; Jarrahi and Nelson, 2018; Mowbray et al., 2017), and importance of a holistic and dynamic perspective to information activities instead of assuming that they take place in closed contexts and as discrete activities (e.g., Cox, 2013; Huvila and Ahmad, 2018).

The prospects of describing contexts in a centred-set-like fashion can be exemplified also in other contexts of library and information science. Different aspects or facets of contextual metadata (e.g., those in Weaver, 2007) can be conceived as things (white dots in Figure 3) with certain closer or more remote relatively stable, approaching or distancing affinities to a concept (black dot A) described in a knowledge organiz ation system. To give one more example, also the contemporary understanding of contextual landscape of public libraries can be conceived as a centred set. In the light of the model of Jochumsen and colleagues (2010) contextual aspects (white dots in Figure 3) that approach public library (black dot A) are expectations of supporting experiences, involvement empowerment and innovation whereas contextual aspects or expectations that are distancing are, for instance, relating to public purposes (Buschman, 2005), enlightenment ideals (Skøtt, 2018) and traditional professional norms (Audunson, 1999).

Discussion

Having proposed an alternative to the criticised (e.g., Dervin, 1997; Dourish, 2004) tendency to explicate context as a container or an unspecified field, it is necessary to underline that in some cases such a conceptualisation can still be useful. For example, when exploring the boundaries and boundedness of communities, how and where informing, interpreting the world and knowing happens, a container-like metaphor of frame – including frames of mind and frame of reference (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980), small worlds (Chatman, 1991), or a box that bounds our view of available, trustworthy, relevant and pertinent information (Huvila, 2012) can be useful. In these cases and, for instance, when using spatial metaphors of the loci of information activities, there is, however, a difference between a naive view of treating context de facto as a container, or using the theoretical concept in an analytic sense to highlight specific aspects of information activities and their constituents. Such an approach is useful, for example, in articulating the boundaries of contexts, and as notion of bounded sets suggests, what falls within the limits of the set and what things lie outside of its perimeters.

Further, it is necessary to underline that the proposed approach is not aiming at providing a new definition of what context is. It is rather an attempt to propose a way of thinking and imagining about context. In case a researcher considers it helpful, it is also possible to draw a diagrammatic visualisation of how a specific context might be conceived as a centred set. The drawing is, however, not to be confused as being a model or definition of context per se but rather a visual depiction of a theory or way of thinking about contexts. As Doing (2008) underlines, visual depictions can be powerful means to communicate ideas, but at the same time, it is problematic when researchers sometimes base their inferences on visual representations. It is not too far-fetched to suggest that the literal readings of how contexts are depicted (but not necessarily meant to be interpreted) in library and information science related models is a part of the problem that has led to dissatisfaction of how contexts have been treated in the literature. Therefore the notation and direction of influences is secondary to opening up contexts for inquiry in novel ways. As such the proposed imaginary allows for both theory and observation driven inquiry (cf. Smith, 2005) and using the notion of centred-set as a model proper but also as a metaphor or analogy (Haraway, 2016, p. 63). As noted earlier in this text, the key benefits of imagining contexts as centred sets apart from the definite shift of emphasis from treating them as containers is how the approach makes it easier to articulate the relative impact and significance of parallel contexts and, depending on the perspective, factors or actors that make the context or that are its constituents. In centred sets, contexts and/or contextual (f)actors do not merely relate to each other but they have specific and articulatable affinities to each other as exemplified earlier in this text in the context of work-life, metadata and public libraries.

Much similarly to ANT (cf. Tabak, 2014), conceiving (human and non-human) actors and their contexts as a centred set de-essentialises them as things and turns attention to them as relational entities. If it is helpful in an on-going inquiry, the centred sets can be conceived further, and in the end replaced by, actor-networks where actors and contextual entities become actors (or actants as for Latour, 2005a) in a common mesh of relations. Instead of inquiring into actors and their contexts, this step would help us, as Tabak suggests, stop “jumping between context and users” (Tabak, 2014, p. 2223) and to trace information practices (and behaviour) by tracing “sequential events of scripting that keep the circulation of individualization and collectivization, in which information and users, the cognitive and social, humans and nonhumans, individual and collective constantly exchange properties” (Tabak, 2014, p. 2231).

Acknowledging the usefulness of the approach of going beyond context, as the author of this text I am, however, also inclined to believe that sometimes the jumping can be analytically useful. When trying to do this, it is problematic, however, if we have failed to pinpoint from where to where we are supposedly jumping. An alternative to ANT is to consider Barad’s (2007) agential realism that focuses on the materiality and actions within actors as a condition that produces phenomena instead of assigning agency to relations and negotiation. Instead of focusing on information interactions in context (criticised by Saracevic, 2010) or in the context of a network (as in ANT), informational phenomena (e.g., use, practices, interactions) can be imagined as information intra-actions where informational agency is not held by discrete beings or things but emerges through the ontological separability of intra-acting agencies within the context-as-centred-set. From this perspective, context is, as Saracevic suggests, a part of the interaction (Saracevic, 2010), or following Barad, intra-action. It is not separate from actors but can be temporarily enacted as a separate entity by making an agential cut (Barad, 2007) in order to open it up for observation to gain knowledge about it. Barad is making a similar observation to that classifications or fine lines (Zerubavel, 1991) between entities or spaces of experience (Koselleck, 2004) make things imaginable and manageable. Drawing lines between actors and the constituents of their contexts is an act of doing these cuts. This can of course be taken as a literal enactment in the spirit of Barad’s onto-epistemology or as an analytical exercise informed by other meta-theoretical perspectives. A common denominator of all these alternatives is that they hold promise in helping to avoid misusing context as a generic unspecific explanation to phenomena that are difficult to explain, and instead, acknowledging it as a concept, something substantive and specific, that needs to be explained properly when used.

Conclusions

Probably the most significant conclusion that can be drawn from the past two decades of library and information science research since the contextual metatheory was, in a sense, launched as a mainstream approach in the field at the first ISIC (originally Information Seeking in Context) conference in Tampere, is that many of the challenges painted then in the introductory paper of Vakkari (1997) are still here. Similarly to how it is not enough to state that information practices and behaviour are complex phenomena, it is not very much and definitely not enough to say that information interactions are context-dependent and leave it there.

I have proposed in this text that the notion of centred set could provide useful means to rethink context and to help to avoid the temptation to treat it as an unspecified container. This can be helpful in being more mindful about contexts and their limits in the spirit of what Johnson (2003) suggested already some time ago. Instead of seeing context as a single- or multi-layered surrounding (or a bounded or semi-bounded set of things), describing it as a centred set makes it a position with affinities to different factors, situations, people or things. Whether it is primarily an enumeration of these (f)actors, a carrier of meaning (cf. Dervin, 1997) in itself, a starting point for conceiving it as a part of an actor-network (cf. Tabak, 2014), or a temporary separation of inseparable intra-acting agencies (cf. Barad, 2007), depends on the aims of explicating context. Combined with the reconceptualisation or (re)emphasis of information interactions, activities or practices as intra-actions, it can provide new perspectives to how to approach context in empirical research as a specific and analytically useful concept rather than taking it, literally, as a mere context or discarding it altogether.

Acknowledgements

This work has benefited of the discussions at different events organized by the COST Action ARKWORK, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology). Earlier ruminations of the same topic were discussed as a part of a poster ‘In search of analytical categories between the holism and contextuality of information behaviour’ presented at the SIG USE 2018 Annual Research Symposium in Vancouver at the ASIS&T 2019 Annual Meeting. I would also like to thank Dr. Michael Olsson and two anonymous reviewers for insightful comments and critique.

About the author

Isto Huvila holds the Chair in Information Studies at the Department of ALM (Archival Studies, Library and Information Science and Museums and Cultural Heritage Studies) at Uppsala University in Sweden, and is Adjunct Professor (docent) in Information Management at Information Studies, Åbo Akademi University in Turku, Finland. Huvila is chairing the COST Action ARKWORK and is directing the ERC funded research project CAPTURE. His primary areas of research include information and knowledge management, information work, knowledge organization, documentation, and social and participatory information practices. He can be contacted at isto.huvila@abm.uu.se.

References

- Acker, W. V. & Uyttenhove, P. (2012). Analogous spaces: An introduction to spatial metaphors for the organization of knowledge. Library Trends, 61 (2), 259–270.

- Agarwal, N. K. (2017). Exploring context in information behavior: Seeker, situation, surroundings, and shared identities. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool.

- Andersen, J. (2017). Genre, the organization of knowledge and everyday life. Information Research, 22 (1), paper 1647. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/22-1/colis/colis1647.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2YUvUQV)

- Anderson, T. (2007). Settings, arenas and boundary objects: socio-material framings of information practices. Information Research, 12 (4). Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/12-4/colis/colis10.html(Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/31vS65G)

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe half-way. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Borlund, P. (2016). Interactive information retrieval: An evaluation perspective. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM on Conference on Human Information Interaction and Retrieval, CHIIR ’16, (pp. 151–151). New York: ACM.

- Broadbent, S. (2016). Intimacy at work: how digital media bring private life to the workplace. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press.

- Burnett, G. (2015). Information worlds and interpretive practices: Toward an integration of domains. Journal of Information Science Theory and Practice, 3 (3), 6–16.

- Burnett, G. & Jaeger, P. T. (2008). Small worlds, lifeworlds, and information: The ramifications of the information behaviour of social groups in public policy and the public sphere. Information Research, 13(2). Retrieved from http://informationr.net/ir/13-2/paper346.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2GZUqKp)

- Chang, S.-J. L. & Lee, Y.-Y. (2001). Conceptualizing the context and its relationship with information behavior. The New Review of Information Behaviour Research, 2, 29–46.

- Chatman, E. A. (1991). Life in a small world: Applicability of gratification theory to information-seeking behavior. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42 (6), 438–449.

- Chatman, E. A. (1992). The information world of retired women. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Choo, C. W. (2007). Information seeking in organizations: epistemic contexts and contests. Information Research, 12 (2). Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/12-2/paper298.html(Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2OLs0tJ)

- Clarke, A. E. & Star, S. L. (2008). The social worlds framework: A theory/methods package. In E. J. Hackett, O. Amsterdamska, M. Lynch & J. Wajcman (Eds.) The handbook of science and technology studies, (pp. 113–137). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, (3rd ed.).

- Courtright, C. (2007). Context in information behavior research. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 41 (1), 273–306.

- Cox, A. M. (2013). Information in social practice: A practice approach to understanding information activities in personal photography. Journal of Information Science, 39 (1), 61–72.

- Dervin, B. (1997). Given a context by any other name: methodological tools for taming the unruly beast. In ISIC ’96: Proceedings of an international conference on Information seeking in context, (pp. 13–38). London, UK: Taylor Graham Publishing.

- Dervin, B. & Foreman-Wernet, L. (2012). Sense-making methodology as an approach to understanding and designing for campaign audiences. In R. E. Rice & C. K. Atkin, R. E. Rice & C. K. Atkin (Eds.), Public Communication Campaigns (pp. 147–162). Los Angeles: Sage.

- Dijk, T. A. v. (2008). Discourse and context: A sociocognitive approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dourish, P. (2004). What we talk about when we talk about context. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 8 (1), 19–30.

- Fisher, K. E., Durrance, J. C. & Hinton, M. B. (2004). Information grounds and the use of need-based services by immigrants in Queens, New York: A context-based, outcome evaluation approach. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 55, 754–766.

- Ginman, M. (1988). Information Culture and Business Performance. IATUL Quarterly, 2 (2), 93–106.

- Gregg, M. (2011). Work’s Intimacy. Cambridge: Polity.

- Habermas, J. (2004). Autonomy and solidarity: interviews with Jürgen Habermas. London: Verso.

- Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble : making kin in the chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hartel, J., Cox, A. M. & Griffin, B. L. (2016). Information activity in serious leisure. Information Research, 21 (4). Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/21-4/paper728.html(Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2yUnSwZ)

- Hiebert, P. (1978). Conversion, culture, and cognitive categories. Gospel and Context, 1 (4), 24–29.

- Hjørland, B. (2004). Domain analysis: A socio-cognitive orientation for information science research. Bulletin of ASIS&T, 30 (3), 17–21.

- Huizing, A. & Cavanagh, M. (2011). Planting contemporary practice theory in the garden of information science. Information Research, 16 (4). Retrieved from http://informationr.net/ir/16-4/paper497.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2ZU1Oyh)

- Huotari, M.-L. & Chatman, E. (2001). Using everyday life information seeking to explain organizational behavior. Library & Information Science Research, 23 (4), 351–366.

- Huvila, I. (2008). Work and work roles: a context of tasks. Journal of Documentation, 64 (6), 797–815.

- Huvila, I. (2009). Analytical information horizon maps. Library and Information Science Research, 31 (1), 18–28.

- Huvila, I. (2012). Information Services and Digital Literacy: In search of the boundaries of knowing. Oxford: Chandos.

- Huvila, I. (2013). How a Museum Knows? Structures, Work Roles, and Infrastructures of Information Work. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64 (7), 1375–1387.

- Huvila, I. (2016). Affective capitalism of knowing and the society of search engine. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 68 (5), 566–588.

- Huvila, I. & Ahmad, F. (2018). Holistic information behavior and the perceived success of work in organizations. Library & Information Science Research, 40 (1), 18–29.

- Jacob, E. K. (2001). The everyday world of work: Two approaches to the investigation of classification in context. Journal of Documentation, 57 (1), 76–99.

- Jaeger, P. T. & Burnett, G. (2010). Information worlds: social context, technology, and information behavior in the age of the Internet. New York: Routledge.

- Jarrahi, M. H. & Nelson, S. B. (2018). Agency, sociomateriality, and configuration work. The Information Society, 34 (4), 244–260. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2018.1463335 (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2KtySYH)

- Jeffreys, H. & Jeffreys, B. S. (1988). Bounded, unbounded, convergent, oscillatory. In Methods of Mathematical Physics, (pp. §1.041, 11–12). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, (3rd ed.).

- Johnson, J. D. (2003). On contexts of information seeking. Information Processing & Management, 39 (5), 735–760.

- Just, W. & Weese, M. (1997). Discovering modern set theory, vol. 2. Providence: American Mathematical Society.

- Koselleck, R. (2004). Futures past on the semantics of historical time. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Latour, B. (2005a). Reassembling the social: an introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Latour, B. (2005b). What is given in experience? a review of Isabelle Stengers’ Penser avec Whitehead’. Boundary 2, 32 (1), 222–237.

- Lloyd, A., Pilerot, O. & Hultgren, F. (2017). The remaking of fractured landscapes: supporting refugees in transition (spirit). Information Research, 22 (3), paper 764. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/22-3/paper764.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2KtOTh6)

- McKenzie, P. (2003). A model of information practices in accounts of everyday-life information seeking. Journal of Documentation, 59 (1), 19–40.

- Mowbray, J., Hall, H., Raeside, R. & Robertson, P. (2017). The role of networking and social media tools during job search: an information behaviour perspective. Information Research, 22 (1), paper 1615. Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/22-1/colis/colis1615.html(Archived by the Internet Archive athttp://bit.ly/2MTkHO9)

- Normore, L. (2011). Information needs in a community of reading specialists: what information needs say about contextual frameworks. Information Research, 16 (4). Retrieved from http://informationr.net/ir/16-4/paper496.html(Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2YDYivr)

- Pettigrew, K. E. (1999). Waiting for chiropody: contextual results from an ethnographic study of the information behaviour among attendees at community clinics. Information Processing and Management, 35 (6), 801–817.

- Purves, R. S., Winter, S. & Kuhn, W. (2019). Places in information science. Forthcoming in JASIST.

- Saracevic, T. (2010). The notion of context in "Information Interaction in Context". In Proceedings of the third symposium on Information interaction in context, IIiX ’10, (pp. 1–2). New York: ACM.

- Savolainen, R. (1995). Everyday Life Information Seeking: Approaching Information Seeking in the Context of ¨Way of Life¨. Library and Information Science Research, 17 (3), 259–94.

- Savolainen, R. (2006a). Spatial factors as contextual qualifiers of information seeking. Information Research, 11 (4). Retrieved from http://informationr.net/ir/11-4/paper261.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2YDCRuk)

- Savolainen, R. (2006b). Time as a context of information seeking. Library & Information Science Research, 28 (1), 110–127.

- Savolainen, R. (2008). Source preferences in the context of seeking problem-specific information. Information Processing & Management, 44 (1), 274–293. Evaluation of Interactive Information Retrieval Systems.

- Savolainen, R. (2012). Conceptualizing information need in context. Information Research, (4) , 17. Retrieved from http://informationr.net/ir/17-4/paper534.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2YX0Bc9)

- Sazonov, V. (1997). On bounded set theory. In M. Dalla Chiara, K. Doets, D. Mundici & J. van Benthem (Eds.) Logic and Scientific Methods, (pp. 85–103). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Sonnenwald, D. H. (1999). Evolving perspectives of human information behavior: Contexts, situations, social networks and information horizons. In T. D. Wilson & D. K. Allen, T. D. Wilson & D. K. Allen (Eds.), Exploring the Contexts of Information Behavior (pp. 176–190). Cambridge: Taylor and Graham.

- Sonnenwald, D. H. & Wildemuth, B. M. (2001). Investigating Information Seeking Behavior Using the Concept of Information Horizons. University of North Carolina, School of Information and Library Science. Retrieved from http://sils.unc.edu/research/publications/reports/TR-2001-01.pdf

- Tabak, E. (2014). Jumping between context and users: A difficulty in tracing information practices. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 65 (11), 2223–2232.

- Talja, S., Keso, H. & Pietiläinen, T. (1999). The production of ´context´ in information seeking research: a metatheoretical view. Information Processing and Management, 35 (6), 751–763.

- Talja, S., Tuominen, K. & Savolainen, R. (2005). “Isms” in information science: constructivism, collectivism and constructionism. Journal of Documentation, 61(1), 79–101.

- Thomas, N. P. & Nyce, J. M. (2001). Context as Category: Opportunities for Ethnographic Analysis in Library and Information Science. The New Review of Information Behaviour Research, 2, 105–118.

- Tuominen, K., Talja, S. & Savolainen, R. (2002). Discourse, cognition, and reality: toward a social constructionist metatheory for library and information science. In H. Bruce, R. Fidel, P. Ingwersen, & P. Vakkari, H. Bruce, R. Fidel, P. Ingwersen & P. Vakkari (Eds.), Emerging Frameworks and Methods: CoLIS 4 : Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Conceptions of Library and Information Science, Seattle, WA, USA, July 21-25, 2002 (pp. 271–283). Greenwood Village, CD: Libraries Unlimited.

- Vakkari, P. (1997). Information seeking in context: A challenging metatheory. In P. Vakkari, R. Savolainen & B. Dervin (Eds.) Proceedings of an International Conference on Research in Information Needs, Seeking and Use in Different Contexts, (pp. 451–464). London: Taylor Graham.

- Waller, V. (2011). Not just information: Who searches for what on the search engine Google? Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(4), 761–775.

- Widén-Wulff, G. (2000). Business information culture: a qualitative study of the information culture in the Finnish insurance industry. Information Research, 5(3). Retrieved from http://informationr.net/ir/5-3/paper77.html (Archived by the Internet Archive at http://bit.ly/2ZSdUYX)

- Wilson, T.D. & Walsh, C. (1996). Information behaviour: an interdisciplinary perspective. British Library Research & Innovation Centre (British Library Research and Innovation Report 10). Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/tdw/publ/infbehav/prelims.html

- Zerubavel, E. (1991). The fine line: making distinctions in everyday life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

How to cite this paper

| Find other papers on this subject | ||

|

|

© the author, 2019. Last updated: 14 December, 2019 |