Using an infrastructure perspective to conceptualise the visibility of school libraries in Sweden

Ulrika Centerwall and Jan Nolin

Introduction. An emerging research area within the social sciences is infrastructure studies. This article conceptualises school libraries as an infrastructure among others, allowing for a fresh look at the role of the school library. We review and discuss what constitutes the school library as an important infrastructure at a school site.

Method. Empirical data drawn from a qualitative interview study, including qualitative observations of Swedish school libraries was analysed using the concept of infrastructure.

Analysis. The analysis was conducted with the support of a model including structures and arrangements of infrastructures.

Results. A central objective of school library practices is to make the library more visible as one of the infrastructures of a school site. Different aspects of school library infrastructure can work for and against visibility.

Conclusions. By conceptualising school libraries as an important infrastructure among others at school sites, it was possible to develop a deeper understanding of school library practices and visibility. Findings from this study contribute to the research on school libraries as contested functions within the context of schools.

Introduction

Infrastructure studies build on the notion that infrastructure encompasses more than hardware, such as roads, railways and pipes (e.g., Larkin, 2013). It has been argued that discussions, strategies and investments concerning infrastructure tend to be misleading, as they often ignore the invisible workers who build and service the hardware (Bowker, Baker, Millerand and Ribes, 2010). Therefore, studies have aimed to investigate the complexity of infrastructures.

School libraries stand out in relation to other library types as being one of the functions within a larger educational institution. The isolated positions held by school libraries make them interesting to study with infrastructure theories to generate new insights. The current text is part of a larger project aiming to explore theoretical viewpoints regarding school libraries. Different contributions within the project are therefore aimed at testing the potential of a variety of perspectives. Infrastructure theory appears to be promising as a theoretical tool through which school library practices are deemed of equal importance with other infrastructures at the school site, not merely supporting that which happens in the classroom. The current approach is also inspired by the notion of site from Schatzki (2002; 2010).

The article will also introduce several fruitful concepts to explore the constitution of the school library as an important infrastructure in schools. This is done in the context of addressing the following research question: How can an infrastructure approach be useful to make school libraries visible and what new knowledge can be developed within such a perspective?

The approach of this article is to view schools as sites for a multitude of practices that are supported by various infrastructures. Theoretically, this approach connects to one of the central ambitions within infrastructure studies, to make the invisible visible (Star and Ruhleder, 1996).

The concept of school libraries is used in this article to describe libraries or media (resource) centres in primary, secondary and upper-secondary schools serving pupils between the ages of six and nineteen. Furthermore, school libraries are viewed not just as facilities with collections of media and resources, but also as places where professionally trained and/or qualified librarians and/or teacher-librarians work with teachers and pupils using specific skills.

At the outset of this article, previous school library research will be reviewed and the theoretical framework outlined. Thereafter, in the method section, the empirical data generated by a qualitative study of Swedish school libraries is presented. The results and analysis are obtained by applying the model presented in Figure 1, which focuses on the structures and arrangements of the school library. The article finishes with conclusions drawn from the study.

Literature review

School libraries are required to adapt to national educational policies, such as the Educational act, as well as to local school traditions and prerequisites for development of unique school library practices. The role of the individual library at each specific school is negotiated between management, teachers, pupils and librarians. Previous research on school libraries is rather scant compared to investigations of other library types. Development of appropriate theoretical perspectives has been slow (cf, Gärdén, 2017).

School libraries have been developed as part of the wider library and information network in accordance with, for example, the principles of the IFLA and UNESCO school library manifesto. In the manifesto it is suggested that the school library should offer ‘learning services, books and resources that enable all members of the school community to become critical thinkers and effective users of information in all formats and media’ (IFLA..., 1999, para. 1 ). Even though the ideals of UNESCO have been formative, there are substantial local variations. For instance, the American Library Association states that the mission of the school library is ‘to ensure that students and staff are effective users of ideas and information’ (American Association of School Librarians & Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 1998). Comparatively, the IFLA School Library guidelines from 2015 (Schultz-Jones and Oberg, 2015) emphasise the importance of the school library as a support for teaching and learning at schools. According to IFLA the goal of all school libraries is to develop information literate pupils who will become responsible and ethical participants in society.

A school library is a specialised library with the character of an educational library, similar to the academic library. In Sweden, the school inspectorate defines school libraries as a ‘communal and orderly resource of media and information made available to pupils and teachers … who undertake to support pupils’ learning’ (translated from Swedish original, Swedish School Inspectorate, 2011, p. 5). However, despite these guidelines we know that school libraries in Sweden devote most of their time to the promotion of reading (Limberg and Lundh, 2013a). To study visibility is not entirely new in school library research. In 1994 Stratfield and Markless reported an American national research programme on the role of school libraries in teaching and learning with the title Invisible learning (Stratfield and Markless, 1994). They identified much of the work of the school librarian as having a hidden, or taken for granted, character. In 1997 Hartzell introduced the term invisible professional. Referring to librarianship she talks about,

- teachers lacking education of the value of libraries and librarians,

- difficulties in measuring the classroom value of librarians,

- school librarians lacking visibility in professional organizations of educators (Hartzell, 1997, p. 24-29).

As part of a study on the pastoral care of pupils Shaper and Streatfield draw the conclusion that the pastoral care is an ‘often unsung third strand’ of the school librarian’s role (2012, p.74). Arguably, school libraries suffer higher problems of visibility than other library types. To determine if a library can be recognised as having low or high visibility, Lawton (2015) used five questions to ascertain the level of visibility for a school library:

- Is the library recognised by name?

- Is it clear for visitors how to get to the library?

- Do readers know where the library is located within the building?

- Do people know or understand what the library has to offer?

- Do people value the library as an institution? (Lawton, 2015, p. 215)

Taking a professional perspective, Todd states that the question of visibility ‘has plagued the school library profession’ (2012, p. 8). Todd holds the view that the body of school library research, which tends to be on advancing school goals, instruction, curriculum and leadership can add to the understanding of the dynamics of visibility (2012, p. 9). Furthermore, scholars and professionals agree on the need for more visibility (cf. Ballard, 2008; Hartzell, 1997; Shaper and Streatfield, 2012; Todd, 2012). Through an infrastructure perspective we are in the current text able to explore the visibility of the school library in an innovative way.

The infrastructure approach of this article aligns with previous research that has conceptualised the school library as both virtual and physical, as well as local and global (Limberg and Alexandersson, 2003). Furthermore, the school library can be seen as part of a complex and dynamic school site involving a multitude of practices that shift over time. Therefore, the school library meets substantial changes in conditions and practices, depending on shifts in politics, pedagogics and technology (cf, Limberg and Lundh, 2013b). In recent years emphasis has shifted gradually from books and other media to an interest in computer-based learning and the use of digital media (Alexandersson and Limberg, 2012; Huvila, Holmberg, Kronqvist-Berg, Nivakoski and Widén, 2013; Lewis, 2016). Owing to the increasing use of broadband and wireless Internet it has become ever more vital for schools to develop the information literacy of their pupils (cf, Sundin, 2015). Within the school library field there is a clear awareness of this challenge and its importance for new ways of working and thinking about school libraries, a challenge which is reflected in, for example, policy documents and professional network discussions.

Discrepancies between the different professional groups that are active in schools and in their understanding of school libraries have been accounted for in previous research (cf, Cooper and Bray, 2011; Hartzell, 2002). Furthermore, studies of the ways in which school library media programs affect academic achievement reveal that planning and collaboration between school librarians and teachers positively influence pupils’ learning processes (Cooper and Bray, 2011; Lance, 2002; Lance, Rodney and Schwarz, 2010; Markless and Streatfield, 2013). To study school libraries in relation to pupils’ achievements is one area of school library research. Pioneering work in this area was carried out by Gaver in 1963 (Farmer, 2006; Hartzell, 2002). Her studies were followed by many others, mostly American, so called school library impact studies (e.g. Lance, 2002) or empirically-based studies (Gretes, 2013; Todd, 2012).

Infrastructure theory

Before exploring the potential of talking about school libraries as infrastructure, we must first articulate what an infrastructure can be for the purposes of this text. There is a wide range of positions regarding what an infrastructure is. In the following, we will borrow from several different perspectives to construct a usable approach for analysing school libraries.

The main thrust of any kind of infrastructure perspective is to position certain practices in the foreground and others in the background (Star, 1999). However, Star and Ruhleder (1996) emphasise that infrastructures are relational and that what is seen to function in the background depends on the type of activity involved. Consequently, different infrastructures shift from background to foreground. To a substantial extent, such shifts are associated with people moving from one place to another within the school and infrastructures having different functions for them.

The infrastructure approach of this article is also influenced by some basic notions from practice theory. The concept of practices has been defined in numerous ways. Schatzki (2002) conceptualises practices as sayings and doings in which relationships between people and things are organized and arranged in time and space. Leaning on Schatzki (2010), Kemmis et al. (2014) thus conceptualise practices as involving sayings, doings and relatings that occur at sites. In our understanding the school is a site of numerous practices (Schatzki, 2002). Pilerot and Limberg (2011) understand a practice as ‘composed of a set of actions that are organized by understandings of how to do things; by rules; and by teleoaffective structures, i.e., beliefs, hopes, expectations, emotions and moods that have bearing on what is being done’ (p. 315). Although practice theory offers a rich array of interpretive tools when approaching specific sites, we use it solely as a support for the infrastructure approach.

In general, the school focuses on learning and pupils. However, the school engages in a multitude of practices related to various designated tasks. Some of these are regulated in policies and curricula, while others are intrinsic or embodied. Furthermore, some of the practices at a school site can be described in terms of formal or informal learning. However, from a practice theory approach it can be problematic to approach the site with preconceived labels and notions about what is going on. Rather, the school can be seen as ‘a site of the social’ (Schatzki, 2002), a platform for sayings and doings. Shifting the understanding of the site from a place of learning to a place of social practices allows other kinds of understandings, beyond what is commonly pursued within educational research. In consequence, the classroom can be regarded as one site for sayings and doings and the school library as another site with other forms of activities. In such an approach, there are no preconceived assumptions regarding hierarchical relationships. Practices enacted within the school library are seen as connected to other sites, but not as subordinate to them.

Usually, the classroom is seen as the most central and visible infrastructure at the site of the school. From such a perspective, many of the other involved infrastructures are geared towards supporting the doings and sayings of the classroom. This is a common view in educational research (Lu, Chin-Chung and Wu, 2015; Ott, 2017; Stevens, 2016). However, again, it can be seen as a problem that other infrastructures are not really recognised as producing other values beyond support of classroom practices. The approach of this study is therefore to view the school as a site involving a broad range of school practices. Several infrastructures enable the sayings and the doings at the school site. To describe and make manifest various kinds of invisible work, it can be instructive to view all of the infrastructures as equally important. This symmetrical approach is a methodological strategy, allowing a fresh look at what goes on at the school site, where teacher-led classroom practices are not ascribed a privileged position. This is yet another reason why we in our analysis take the perspective of the school library.

The concept of infrastructure

The concept infrastructure is most commonly used when referring to physical structures and facilities serving the economy, typically roads, railways, electrical networks, docks, sewers and water supply. The innovation of the Internet, slowly emerging from the 1960s, created a foundation for talking about telecommunication networks as infrastructure. Notably, during an influential speech in 1986, US Senator Al Gore talked about the evolution of a ‘telecommunication highway’ (Wiggins, 2000). The use of ‘highway’ as a metaphor can be seen as a way of communicating the potential of the Internet in a more concrete way, i.e., as infrastructure. The Internet itself did not reach a broad popular breakthrough until the mid-90s. The World Wide Web, a bundle of protocols that ran at the upper level of the Internet, was introduced in 1991. Following this, the metaphor of surfing the web started to gain popular acceptance. This also involved concrete associations with physical travel. Given such developments in technology and language, the concept of infrastructure emerged as a means of understanding the networked devices of information technology.

Infrastructure studies

In their seminal paper on infrastructure, Star and Ruhleder (1996) characterised the traditional hardware view of infrastructure as mythological, arguing that the crucial involvement of people and organizations in the construction and maintenance of technology was ignored. There was a kind of double invisibility involved in this rethinking of the concept. Star and Ruhleder (1996) emphasised the fundamental character of well-functioning supporting infrastructure running in the background and as such taken for granted. However, the people involved in making and maintaining infrastructure tend, to an even greater extent, to be invisible workers. These insights spurred several Science and Technology Studies (STS) to render the various aspects of infrastructure more visible (Edwards, 2003; Ribes and Baker, 2007; Star, 1999). The current study builds on that tradition.

Star and Ruhleder (1996) were inspired by Jewett and Kling (1991) who argued that infrastructures should never be understood merely as thing, but rather as relation. Different people and practices have separate infrastructures for various activities. For instance, those maintaining bridges or sewers rely on other infrastructures to allow them to do what they do. In this sense, people utilise various infrastructures for different tasks, relying in various situations more on some than on others.

This study is also inspired by an approach within educational research on infrastructure (Guribye, 2005; Guribye and Lindström, 2009). Guribye (2005) suggests that infrastructures ‘comprise a foundation for how we go about living our lives’ (p. 9). This is a broad definition with both strengths and weaknesses. Seemingly, just about everything (and anybody) can be talked about as infrastructure. However, the strength of this approach is that it permits an extensive and non-biased inventory of available infrastructures. This aligns well with the ambition of this article to situate and investigate school libraries as one of several infrastructures at the site of the school. The definition can also be used as a foundation for looking specifically at certain practices.

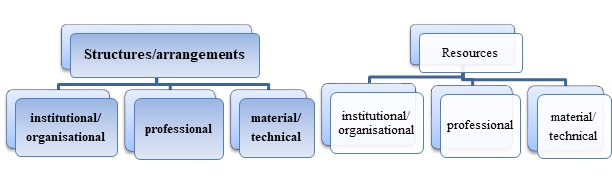

Further, Guribye and Lindström (2009) defines an infrastructure for learning as ‘a set of resources and arrangements – social, institutional, technical – that are designed to and/or assigned to support a learning practice’ (p. 154). Bowker and colleagues (2010) state that to understand an infrastructure, the technical, social and institutional activities need to be examined. This led us to construct a model for analysis (figure 1.) with the starting point that school libraries can be seen as a set of institutional, professional and technical structures, arrangements and resources that support various practices going on at schools. However, this definition is limited by the fact that school libraries not only support other practices but also have their own practices. Furthermore, various other practices in schools can be seen as supporting the school library. We see school libraries as infrastructures consisting of institutional, organizational, professional, material and technical structures, arrangements and resources that support various practices going on at schools.

For the infrastructure to function well it requires structures and arrangements, as well as resources. All of these have institutional, organizational, professional, and material and technical aspects. In addition, structures, arrangements and resources must also be aligned with and connected with other involved infrastructures. However, to find a way to describe the infrastructure of the school library we separated structures and arrangements from resources (see Figure 1). Consequently, in the results and analysis section we identify the institutional, organizational, professional, material and technical structures and arrangements of Swedish school libraries, the lack of necessary structures and arrangements, as well as problems in connection with other infrastructures.

Infrastructures at the school site

Building on previous research, as well as empirical data, we have identified nine infrastructures that in varying degrees interact and support each other, the pupils and the school as a whole. The infrastructure of the school site can be conceptualised in various ways. For the purposes of this article, we have identified nine infrastructures connected to different professions or occupations and spaces or places.

| Infrastructure/function | Profession/occupation | Space/place |

|---|---|---|

| Administration | Economics, scheduling personnel | Allocated office space, reception |

| Classroom teaching | Teacher, other teaching staff | Allocated office space, classroom, common room, schoolyard |

| Cleaning, maintenance | Cleaners, caretaker | Whole school building |

| Food | Cooks/kitchen staff | Kitchen, restaurant |

| Guidance | Career guidance counsellor | Allocated office space |

| Healthcare (and) guidance | School counsellor, nurse, doctor, school curator | Allocated office space |

| Information technology-service | Information technolgy technician, Information technology or Information and communication technologies teacher | Allocated office space, computer room |

| Library services, librarianship | School librarian | Library, classroom |

| Management, leadership | Principal, school leader | Allocated office and meeting spaces |

The model is a simplification and generalisation of the school site and could thus be further problematised and developed. Some of these infrastructures may not exist at every school, they might be labelled differently, or organized in other ways. However, this model worked well with our methodological approach and at the same time functions as an example of the infrastructures of the Swedish secondary and upper-secondary schools included in our empirical data. Furthermore, for the purpose of viewing school libraries as part of school infrastructure, we have here articulated what an infrastructure can be in this text and borrowed some concepts from a practice theory approach. This entails that practices of school libraries are seen as included within other practices at the school site. The analysis of the data has led to development of new theoretical concepts:

- Infrastructure maintenance: upholding, sustaining or managing the efficient function of an infrastructure.

- Classroom infrastructure maintenance: sustaining the practices and activities of the classroom infrastructure.

- Self-managed library maintenance: librarians maintaining the infrastructure of the library on their own.

- Infrastructure minimisation: an infrastructure supplied a bare minimum of resources, as a consequence being understaffed or mismanaged.

These concepts emerged at a relatively late stage of processing the empirical data, when the lens of infrastructure theory was applied. These concepts were thereafter found useful for discussing infrastructure issues related to school libraries.

Method

Even though schools in the global north have numerous characteristics in common, it must, nevertheless, be recognised that different school sites are shaped by their various national, cultural and local contexts. We will therefore contextualise our study through a presentation of school library practices in Swedish secondary and upper-secondary school libraries. A limitation of this approach is that our empirical data is focused on the school library, although there are several other invisible infrastructures at the school site in need of similar theoretical treatment.

In Sweden, as in many other countries, school libraries frequently suffer from a lack of resources, including professionally educated staff (cf, Gärdén, 2017, p. 25). Bearing this in mind, and as part of a pilot study, observations were conducted at six schools. The pilot study revealed difficulties in finding well-functioning school libraries. Several sites visited in this first phase had poor staffing situations and lacked strategic agendas. Therefore, a strategy was developed for identifying well-functioning school library practices. Consequently, we selected school libraries which had earned awards from a Swedish professional association. The first selection resulted in fourteen interviews with school librarians at upper secondary and secondary public schools. A second round of interviews built on a broader selection to include primary school levels and even some school libraries that not necessarily (but yet in some cases) had been awarded distinctions. The second round of interviews consisted of eight participants. In sum twenty-two librarians at fourteen schools in twelve municipalities have contributed to the overall understanding of Swedish school libraries.

Empirical data

The twenty-two participants interviewed were not asked to account for their age or gender identity, although we assumed from outer attributes that their age ranged from thirty to sixty years and that five participants were male. Experience in librarianship ranged from two years to over twenty years. Several had worked as children’s and public librarians before becoming school librarians. Some of the participants worked in close collaboration or partnership with other professionals such as the information and communication technologies-teacher, information technology-personnel or school attendants, while others had the help of library assistants or teacher-librarians i.e., teachers with some responsibility for library duties, who attended to the information desk during opening hours. Others worked more or less isolated from the rest of the school staff. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with all participants at their workplace, the school library or media centre, between April 2015 and October 2016. The interviews lasted for forty to ninety minutes, they were recorded and transcribed verbatim and the participants were offered the chance to read the transcriptions. The data has been treated with confidentiality and accordingly the participants are given pseudonyms. The study was introduced as a study of the school librarian’s professional role and identity, their daily work and challenges, and their views on work with management, teachers and pupils.

The conversational themes discussed during interviews concerned roles, tasks and general work in and outside of the library, norms in the library and the school, as well as how they worked with such values. As Meyers, Nathan and Saxton (2007) also found, we argue that we cannot know the extent to which our participants take an advocacy stance (cf, Markless and Streatfield, 2013). Rather, what we study are their expressions concerning school library work, together with the impressions we gained from the field visits and interviews with other participants at the same school.

Aiming to understand the practices, as well as the connected problems and challenges , we were interested in where these practices were enacted at the school site; therefore, interviews were combined with observational field visits of the school library. However, the empirical data was mainly generated by interviews. A methodological dimension of this project was that the interviews were characterised by co-construction, in which the interviewing researcher could utilise her previous experiences as a school-librarian (cf, Denzin, 2001). Having worked at both school and public libraries, the interviewing researcher had her own knowledge and views on how to perform the school librarian practices. This relative insider position, together with previous professional experiences, was used in interactions with the participants to enable uninhibited conversations characterised by a climate of trust.

Early on in the interview process it became clear to the interviewing researcher that the narratives which emerged at the different school sites were similar, leading to a sense of saturation (cf, Silverman and Marvasti, 2008). This was indicated by the use of common phrasings and expressions by the participants and also that the interviews tended to dwell on, or skip, the same issues. With the help of Atlas TI the transcripts were analysed to find common themes. The citations were translated from Swedish to English.

The data is used for several articles (e.g. Centerwall, 2019). In this article, however, the focus is on practices through exploring the usefulness of the infrastructure theory. More specifically, the paper focuses on connections to (in)visibility and the concept of infrastructure. The results and analysis section are structured by a mapping of the different practices and thereafter ordering and relating them to the organization, the site, the profession, the materials, as well as relationships with other actors at the school.

Results and analysis: school libraries as part of structures and arrangements of schools

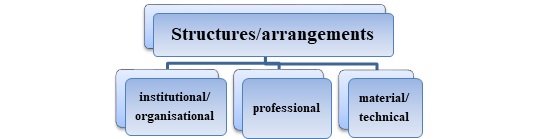

The following section is structured according to the model presented below (Figure 2.) and builds on the empirical data seen through the lens of the infrastructure approach, where the school library is one of nine infrastructures at the school site (Table 1.).

Figure 2: Structures and arrangements of an infrastructure

The different infrastructures at the school site are upheld by workers from different vocations and professions, with various degrees of visibility. Arguably, teachers and pupils are the most visible actors at the school site. Some infrastructures appear to strive to become more visible to teachers and pupils, whilst for others it appears to be a case of becoming more visible to management.

The school site is characterised by infrastructures being fixated with certain spaces and types of staff. Hence, pupils move between different spaces, engaging with specific staff, who attend to various needs. From an infrastructure perspective different spaces are (mainly) served by separate and specialised professions or vocations. These groups of professionals vary, for example in number, educational level, agency, visibility and autonomy in relation to the others. Taking numeracy as an example, teachers stand out as the largest professional group at schools and thus have a high degree of visibility. Similar to, for example, the study counsellor, nurse or doctor, the librarian is often the only representative of the profession. However, our selection of award-winning school libraries were sometimes staffed by two, or in one case even three, professionally educated librarians.

A key aspect for the approach of this article is the relative autonomy of various infrastructures and the professions that maintain them. Of the infrastructures articulated above, the school library is the one most closely aligned with the infrastructure of classroom teaching. Since management places an emphasis on classroom practices, library practices, as well as other practices such as counselling, become situated in a subordinate position. Whilst work in the other infrastructures at the school site could be understood, at least to some extent, as autonomous from teaching practices, this is not the case for the library. Instead our empirical data is filled with statements from librarians strategically aiming to change their subordinate positions to achieve relative autonomy in performing their work and become more visible as important actors in the practices enacted at the school site.

Working through the empirical data, using an infrastructure lens, several new concepts were developed. The first key concept introduced here is infrastructure maintenance, of which there are two main aspects. Firstly, individual infrastructures must be allowed to update, refresh and reinforce involved resources. This can be a matter, among other things, of re-staffing, professional development, buying classroom materials, or acquiring new technology. Secondly, connections between interlinked infrastructures must be tended carefully, for instance in the form of upholding communication between those working in the classroom and the library. Traditionally, the maintenance of the classroom infrastructure is seen as the most important. In our exploratory approach of probing the value of the infrastructure perspective, we suggest that it might be useful to disregard such a classroom-centrist perspective. In doing so, it becomes possible to view classroom infrastructure maintenance as involving activities distributed among many professionals, not only teachers. Crucially, school library staff were involved in classroom infrastructure maintenance.

Institutional and organizational structures and arrangements

Swedish school libraries are regulated locally by each municipality, but with unique national regulation requiring schools to allow pupils access to a school library (Swedish school law, 2010). The school librarians state that both the national and the local frameworks were used as guidance for their work. For example, when local documents appear insufficient the librarians rely on the national policy regulations. Whilst the Educational Act can be a tool in strategic discussions with management, such discussions can also position librarians in an adversarial position in relation to management. Management, usually with a background in teaching, has to allocate resources, but can do so without committing to anything beyond what is here termed infrastructure minimisation, i.e., supplying the minimum required by the letter of the law. For instance, it seemed to be common to bypass the relevant profession and instead staff the library with teachers, IT-staff or trainees.

Infrastructure minimisation is a fundamental difficulty for the library profession in interaction with other professions and overlapping with other infrastructures. Members of other infrastructures can point to specific and necessary tasks to avoid breakdown of functionality. It is more difficult to identify a point of breakdown for the school library. There were many examples in the empirical data (including the pilot) where the school library was just a room with some old books, irregular opening hours, or very poorly staffed. Participants in this study invariably wished for better staffing. However, when visualising their ambition, their views were limited to their actual situations and the reality of the library being minimised, non-prioritised or invisible. After observing variations of severe infrastructure minimisation within the bounds of the pilot study, the sites visited to obtain the empirical data were relatively better equipped, had relatively extensive open hours, as well as several professionally educated school librarians involved in developing collaboration and educational practices. Having said that, infrastructure minimisation remained a substantial problem, even for these libraries.

Star (1999) defined a dimension of the infrastructure as something that becomes visible upon breakdown. In other words, when invisible structures and arrangements of the infrastructure breakdown they can become visible. For instance, a breakdown in the food infrastructure will quickly lead to problems of functionality for all those working at the school. The food infrastructure is upheld by largely invisible workers, but when it breaks down it becomes visible for others. Other functions can in some cases become visible not just upon, but because of, breakdown.

Infrastructure maintenance

Lack of support from management was found throughout the empirical data, either as something experienced earlier in a career, at previous work places, or as a challenge in the present. However, most of the school librarians in this study worked at school libraries that enjoyed, in national terms, uncommon support from management. This was evidenced by funding for library resources or staffing, although the management´s knowledge on school libraries was still questioned.

I don’t think that the management really understands what a great library they have, in every kind of way. (Julian)

Consequently, participants in our study signalled a need for school leaders to create some kind of framework for collaboration, i.e, a document where the teaching role of the librarian is acknowledged. Such a document could support and guide collaboration between librarians and teachers and be seen as an acknowledgment of classroom infrastructure maintenance. Developing appropriate structures would therefore require intensified connections and communication between teachers, librarians and possibly even school leaders in the creation of a framework and particularly in its implementation. When a framework or document was not produced by management, the librarians tended to write such texts themselves.

We’ve constructed a library plan ourselves although it’s not very detailed. Still, management hasn’t asked for anything like that. (Fran)

In doing so, the librarians are then in a sense covering for those that are assigned to lead them. Given management’s lack of knowledge and interest in the development of the school library, we identified what we call self-managed library maintenance. When plans or policies do not exist the librarians tend to construct their own, or point out the importance of making such plans to the management. Lynn explained pressing the school leader on the issue.

I started straightaway by saying that we need a proper plan, we don’t have a document. I’m ambitious enough to write it myself but I don’t think that’s the way it should be. There has to be some kind of plan for what we do and how it should be done. (Lynn)

The librarians had to constitute their own role in the infrastructure by creating links between, and thereby defining, practices. In time, such practices are perceived as obvious and taken for granted as the infrastructure is ‘learned as part of membership’ (Star, 1999, p. 381). This is shown in the empirical data when librarians suggest that they no longer regularly reflect on the lack of management and that the teachers take their services for granted. At the same time, however, it was common to view collaboration between teachers and librarians as something management ought to enforce on the teachers.

I think that the role of the principal is to steer teachers a lot. Partly this forces them [the teachers] to collaborate but also encourages collaboration, and I don’t think that anything like that has actually happened in any way or form. (Shannon)

However, without strategic discussions on what school leaders and teachers want the library to be, the image of the school library is likely to be fuzzy for teachers, as well as for pupils. In the empirical data examples of occasions were given where management have simply ignored the practices of the school library. In such situations it appeared that management did not understand that school librarians needed to be involved in classroom infrastructure maintenance and that effective leadership is required to make progress. A strategy for increased visibility can thus be to initiate discussions on what a school library is, and to articulate a strategic role in classroom infrastructure maintenance. This could be expressed as follows:

It varies a lot why all these people are proud of it [the school library]. Because school libraries can be such multi-facetted places and we work with, and really try to relate to this depth that can exist in a school library. And I think that if you are proud of something, you also take part. (Gil)

According to Star and Ruhleder (1996) the aspect of being taken for granted characterises a well-functioning infrastructure. However, this is not the case for school libraries, since the school library room, as well as its practices, can be visible while at the same time be well-functioning and taken for granted.

There are advantages with relative autonomy and self-managed library maintenance, as librarians talked about the experience of freedom in how to manage the library and in the decisions and choices made. When there was only one librarian, this person was expected to staff the service desk in the library, as this is often regarded as the most important school librarian task from the management point of view. This restricted opportunities to attend meetings, interact with teachers and to teach pupils in classrooms.

The librarians in this study were used to school leaders that perceived classroom teaching as the most important part of school work, and therefore viewed library work merely as a kind of classroom infrastructure maintenance. Some of the librarians agreed with this view, using the word support when identifying their own role and emphasising a view that support is equally as important as teaching. Alex encapsulates the mission for school library work as:

our main mission is to support and contribute to other school activities in order for pupils to maximise their efforts. (Alex)

Other librarians carefully underlined that the function of the library is not just support, but has its own, even more important, agendas and practices. In other words, while some librarians saw a conflict between having a support function or having their own agendas, others saw these different understandings of the school library as possible to combine. In this context librarians needed to construct narratives concerning their practices that signalled legitimacy and importance, trying to figure out, or learn, how to reach out, through various work tasks. In other words, they had to establish some form of relative autonomy as best they could. The librarians could then seek support from other colleagues at the school. Peyton, for example, was working to increase the respect for the library.

It is not so much the respect for the room but rather the respect for me. That this is my workplace. And the teachers are really good at explaining that to the children. (Peyton)

The lack of regulating structures and arrangements at the school site was seen as highly problematic, not only for the librarian, but also for other involved actors. While it became difficult for school librarians to work optimally, the lack of effective guidance also prevented them from facilitating the work of the teachers, i.e, the classroom infrastructure maintenance.

In general, librarians operate in the library and teachers in the classroom. The library room is a site where the school librarian, who in many respects is dependent on teachers for access to classrooms, is the expert, who sets the rules, and makes decisions concerning library maintenance. These institutional structures can be both strengthening and limiting for the professionals. Librarians voiced that the professions should work in each other’s areas and spaces. There are, however, several problems connected to stepping into other professionals’ areas of expertise and, even to physically entering others’ rooms. Librarians are continually faced with the challenge of trying to reach and gain access to pupils in classrooms. Reaching the pupils is sometimes expressed as a goal of school library work.

We can reach as many as possible. That is what we aim for. I do not strive to reach all teachers; I strive to reach all pupils. (Noel)

At the site of the school there are ongoing formative meetings of infrastructure maintenance, but disconnected from librarians. These can take the form of scheduled meetings, phone calls, as well as the use of other information and communication technology tools. The disconnection between such formative meetings and the librarians makes the school library explicitly positioned as something invisibly supporting and maintaining other infrastructures. This is emphasised through continuous infrastructure minimisation, as well as through differences in professional training; exclusion from meetings, as well as exclusion from the intensive evaluating and grading processes.

Summing up then, infrastructure minimisation can take many forms, resulting in staffing restrictions, bypassing the library profession, utilising inappropriate facilities, cutting down on opening hours and mismanagement of information resources. Infrastructure minimisation can also be described as a vicious circle. Lacking distinct management support, librarians in the study signalled the need for formalised guidelines to prioritise, focus on, or avoid certain work tasks. The outcome of the request for formalisation varied from no response from management to collectively drafted policies. This problem can be connected to the vicious circle of infrastructure minimisation. The more the school library seems to be unable to fulfil its tasks, and the less insight management has, the more difficult it becomes for management to visualise a well-functioning school library. Lacking appropriate resources, the infrastructure can become dysfunctional having difficulty in becoming seen as valuable, which in turn can lead to further infrastructure minimisation. Even though the vicious circle is here introduced as a way of understanding the school library, it can be valuable for discussions on other infrastructures at the school site or elsewhere.

Professional structures and arrangements

While the school library should be understood as an infrastructure in its own right, it is also crucial to understand that its level of autonomy is fragile. Therefore, the relative autonomy of librarians is crucial for understanding the school library as infrastructure. Most of the infrastructures at the school site appear to have a high degree of autonomy in relation to each other. At a glance, the autonomy of librarians appears to be similar in nature, as they maintain their own space. However, our empirical data shows a close connection between the relatively well-staffed classroom infrastructure and the school library.

A fundamental aspect of the professional practices of school librarians is that they are not part of the teachers’ community of practice with similarly trained staff (cf, Lave and Wenger, 1991), and therefore tend to be isolated. For instance, a school of around 1000 pupils might have between fifty and 100 teachers, but only one or two school librarians. This was the situation in one of the schools in our study. Self-managing library maintenance owing to systematic understaffing is, again, a fundamental aspect of infrastructure minimisation. The interviewed librarians testified to a sense of being positioned outside the collective formations at the site, experiencing a lack of recognition and belonging in relation to other school professionals (cf, Centerwall, 2019).

Examining the professional structures and arrangements of libraries in schools it was evident that they were organized in and through networks, projects and meetings.

Networks

The school library does not exist in a vacuum, but is part of an institutionalised infrastructure for formal learning that can be conceptualised as the school site. Within this infrastructure various professional networks exist. Spaces for such networks include conferences, meetings, courses and social network sites. The networks can consist of librarians, such as those connecting all kinds of librarians in a municipality; or connecting all school librarians or teacher librarians in a municipality or region; or connecting different kinds of librarians nationally. These are support networks for the library profession, as well as for further education. In the accounts of the librarians participating in this study the networks were also used strategically to gain more visibility.

In this way, there is a professional structure available that transcends the local boundaries of the school site. There may also be networks including librarians at the site of the school. It may be possible to participate in teacher teams, or other kinds of work teams devoted to furthering education in various subject areas.

Projects

Another common form of work is through formalised projects. These can take a variety of shapes, frequently of a temporary character centred around a course and sometimes on a more long-term basis. Although the initiators of the projects can vary, the librarians stated that, in general, they led the projects.

it’s part of our job to search for projects together with the teachers and then they just roll on. (Eddie)

A positive side effect of project work is that it creates collaboration that strengthens the connections between infrastructures. Examples of a common project subject in the Swedish context were projects on school policies and practices regarding democracy, equity or anti-discrimination. In Sweden, with relatively high levels of immigration, as well as an explicit political emphasis on gender equality, such projects are commonly referred to by the librarians in this study as being part of democracy-oriented work and thus, seen as a core mission.

Meetings

In the professional structure of the school, more or less formal meetings between staff are common. Routines and the regularity of meetings vary greatly from weekly, biweekly, monthly or even annually. The meetings range from face to face conversations between two people to meetings between groups, for instance teacher meetings, staff meetings etc.. Thus, in the everyday work of teachers, there are numerous formal or informal meetings that librarians can have sporadic and random access to.

Suddenly you are not summoned to meetings anymore and you don’t know why. You thought that you really had something great going. (Marion)

To have meetings is part of the conventions within schools and various infrastructures are linked to these meetings. Librarians may attempt to gain more access to meetings to become more visible (cf, Cooper and Bray, 2011). Such access may however be of low priority for teachers. A common impression among the participants was that it had to do with lack of time and understanding on the part of teachers.

They have an old fashioned, or maybe not even old fashioned but traditional, incorrect, view of what happens [in a school library]. (Casey)

These outdated or incorrect views of what librarians do, do not match the standards of best practice school libraries (Church, 2008) and this constitutes a substantial problem for school librarians, as does management’s lack of awareness. Frustration over management’s ignorance is a known issue in the school library context and consequently has been documented before (e.g. Ballard, 2008). Furthermore, there are occasions when school librarians try to uphold or maintain other infrastructures active at the school site using their own skills.

I’m their technical support as far as laptops are concerned. The staff is technically immature, and there aren’t many of them that understand the Chromebox. The IT-technician we have has a locked door and limited opening hours. So I help them get it to work. (Darcy)

Adapting the function as information technology support for pupils was a way for the librarian to maintain the information technology infrastructure. In sum, the librarians prefer meetings and to be part of work groups and networks, rather than standing outside of them or being invited at times. Apart from physical meetings the e-mails and e-mail-lists are important means for communication. Collaborative projects can grow through meetings.

Having reviewed institutional, organizational and professional structures and arrangements, we now consider the material and technical.

Material and technical structures and arrangements

School libraries can be seen as existing infrastructures for practices at schools that change when faced with new challenges and functions. For example, given the digital transformation, focus tends to lie on information and communication technology tools and digital artefacts. This entails a risk of missing out on other important aspects, on how these new artefacts are interconnected and intermeshed with the institutional, social and technical arrangements and structures of school libraries (cf, Guribye and Lindström, 2009).

To use the material approach as a theoretical perspective when studying sayings and doings can help make activities in practices visible (cf, Schatzki, 2010; Pilerot, 2014). Leaning on Star (1999), Pilerot (2014) argues that material objects are embedded in social structures and technologies. This entails that they can be described as transparent, invisibly supporting work tasks. Furthermore, Pilerot (2014) argues that objects have the ability to reach beyond time and space and practices. Again, leaning on Star (1999), it is thus possible for objects to be learned through membership in a practice, to shape and be shaped by conventions of that practice and, as infrastructure, become visible upon breakdown.

It should be noted from the outset that everything that happens at the site of the school plays out within various material structures. It is not possible to deal with all kinds of materiality in the context of this article; rather, the focus is on documents and rooms.

The library room

One of the most fundamental aspects of any school library is the room and its location. A form of infrastructure minimisation is to provide a small room, for example a storeroom, with a limited number of non-indexed books and to call it a library. Equally important is the actual dimension of the facilities. Several of the librarians underline the importance of situating the library centrally as ‘the heart’ of the school and how it affects visibility in a positive way. The school library where Brett works had such a location.

We think we’re at the heart and center of the school. Our strategic position is central in this building where the pupils have their common subjects. Administration is located here too as well as the cafeteria, career guidance and some of the other staff. (Brett)

Given the technical developments in recent decades the mission, function and practices of school libraries have transformed the school library from a unit concerned with the utilisation of an internal repository of texts and other media into, at least ideally, a vital part of the infrastructure of the school site. One of the most dramatic aspects of pervasive information technology and the Internet at schools is that pupils have their own Internet access in their pockets through a smartphone and even through other devices. In Sweden, three out of four upper secondary pupils have access to a personal computer or tablet through their school (Swedish National Agency for Education, 2017). However, we encountered infrastructure minimisation, systematic underfunding and mismanagement of the school library. Examples of this could be that the Internet did not work properly in the school library room, there were no computers for the pupils to use, or that lack of funding had led to out of date collections. In several schools the Wi-Fi connection was unavailable to the pupils, or did not work in all areas of the school. At these sites, the school library offered unique access to computers (mainly used to watch films) and Internet (because not every pupil had a smartphone).

Documents

Documents in schools can foster learning, as well as bring professionals and their practices and activities together. They can thus be viewed as material artefacts with both social, as well as mental features, located in the practice (cf, Pilerot, 2014).

As other professionals and workers of the school, librarians are regulated and guided by laws, policies, guiding documents, curricula, etc. The mission statement of the school library contributes to its legitimation in the school as support to various school infrastructures. Regarding the guiding documents, we identified some that are shared by all staff members of the school, such as the national school law and the overarching plans and policies of the school. Other documents guide only one, or a few of the professions at the school; for example the curriculum guides teachers, librarians and other teaching staff, but not caretakers or kitchen staff. In various ways, documents can function as coordinators for activities, directing activities (task lists) as well as goals for certain activities (i.e, policy documents).

Documents, in the form of regulatory texts and policy directives, play at least two roles. First, as discussed above, there is a need for, and often absence of, local texts that can serve as guidance to what the librarians should focus on in a specific school. Given the frequent lack of such documents, it becomes difficult for the librarians to be a part of the otherwise necessary school practices. Not only could such policy documents provide indications of which practices are valued by management, but such documents also legitimise librarian practices. This kind of legitimacy is sometimes needed in relation to the teachers. When the library or library professionals are excluded from policy documents or local guidelines, such texts function as boundaries between practices at the site.

Secondly, the national regulatory documents exercise considerable power and they clearly require the existence of a school library. However, there is also some tension involved in referring to national legislation in professional sites that otherwise are structured by local ideas. In the interview material it was found that in municipalities where local documents regulate school libraries, the librarians often refer to them together with national regulations, such as the school law and curricula.

Having reviewed the material and technical structures and arrangements of the school library as infrastructure, in the following, we will sum up with some concluding remarks.

Concluding remarks

To be able to discuss school libraries as infrastructures in school sites we developed the concepts of infrastructure maintenance, classroom infrastructure maintenance, infrastructure minimisation, and self-managed library maintenance. These concepts revolve around the visibility and autonomy of school libraries and thus proved helpful when discussing school libraries as infrastructures, but could also possibly be used for discussing teaching practices in classrooms or the work of public libraries.

This article also deals with the development of concepts relating to infrastructure studies being brought into school library research, whilst borrowing some ideas from practice theories. This highlights the two different roles that libraries play at schools; the one where they are managing their own infrastructure maintenance and the other where they play a vulnerable yet important role in classroom practices and the school as a whole.

The school is a site of several infrastructures, engaged in a multitude of practices. The classroom where teachers are educating pupils is the most visible and often regarded as the most important. From a classroom perspective other practices are seen as supporting the teaching and learning practices. Arguably, it is the dominating notion of the centrality of classroom practices that creates a context for rendering other infrastructures less visible. The current study should be placed in context with others that investigate practices at school from an infrastructure approach (Guribye, 2005) and with studies of other professions that perceive themselves to be performing invisible work in a similar sense (e.g. Bonini and Gandini, 2016; Szekeres, 2004).

The school library as infrastructure can seem to be backgrounded to classroom teaching. In identifying the school library as one of nine infrastructures, we employed a symmetric approach, where every infrastructure has its own characteristics and importance for practices at schools. Such practices are integrated with each other to some extent, having various and relative autonomy, and thus affect each other substantially.

These conclusions align with earlier research within infrastructure studies, where an infrastructure is typically seen as something that exists in the background, invisible and often taken for granted, but to an even greater extent, the workers themselves remain unrecognised (Bowker, Baker, Millerand and Ribes, 2010; Star and Ruhleder, 1996). We found accounts that aligned with how infrastructure studies discuss the role of invisible workers, silently upholding the functionality of the infrastructures in the background. This covered a range of nuances which have been described in the text. To sum these up, we see two variations in how the library can be an invisible, or hardly visible infrastructure. The library might:

- Not be seen as an infrastructure of value to pupils i.e. insights into the ways in which school libraries are important for enhancing pupils’ learning are lacking.

- Not be seen as valuable for other infrastructures, in particular the teaching part of classroom practices, or for the school site as a whole.

Furthermore, based on our study we argue that the institution of the school library is much more recognised than the invisible workers involved, i.e., library professionals. Similarly, the materials and media were more recognised than the competences of professionally trained librarians as a resource. In conclusion we can point to two aspects of visibility that relate to supplying value to the school site; either as valuable to pupils and learning, or to teaching staff and teaching.

A further conclusion that could be drawn is that the degrees of visibility for school libraries as a function are increasing. It could thus be stated that school libraries are not (completely) invisible in Swedish political agendas. For example, a revision of curricula in 2017 entails changes for the position of school libraries, as there is a greater requirement to help pupils develop source critical abilities and understand digital media, texts and tools. In Sweden, the school library is the responsibility of the principal of each school. This responsibility involves ensuring that the school library is used as a pedagogical resource to develop the literacy and digital literacy of pupils (Swedish national agency of education, 2017).

It should be noted that there are other school infrastructures that can be characterised as invisible, or being held together by invisible workers. As argued above, this could be the case for infrastructures involved in caretaking, economic support, information technology support, career guidance and healthcare. Each of these infrastructures is upheld by a workforce who, to various degrees, can be described as invisible workers. However, there are significant differences between the objectives of these infrastructures. Library professionals working at schools may share some of the problems of invisibility with these other supporting infrastructures, but mostly with infrastructures with educational objectives.

Of the infrastructures mentioned above, it is arguably the school library that has least relative autonomy in relation to classroom practices. Furthermore, the librarian is presumably the only professional, other than teachers, who also have a teaching role, i.e., an unacknowledged role to play in classroom infrastructure maintenance. This means that the two professional groups have a shared concern in skills, study results, democratic issues, critical thinking and source evaluation in a digitalised society. It is therefore problematic when the connection to school libraries is not being made by teachers and management. For those researching and working in the area of school libraries, however, the connection is obvious and the previous research unambiguous.

The problem in the discrepancy between different professions at the school site often lies in different perspectives. Given the understanding of infrastructure as highly complex and invisible to outsiders, it can never successfully be changed by outside actors with regulatory authority (Star, 1999, p. 382). School leaders need therefore to actively discuss the problems and challenges of infrastructure minimisation with librarians to deal with the problem.

The organizational arrangement that positions librarians under a school leader can support or hinder librarians, depending on the quality of management’s contribution. Although it may be impossible to redesign an entire infrastructure, the school librarian and leaders can collaborate on amendments and improvements. In our case, as the school library infrastructure is interwoven with all the other institutional, organizational, professional, material and technical structures and arrangements of the school, it is difficult to find solutions to problems in isolation. A prime example is the way in which the national requirement to provide access to a school library does not also include a stipulation that such a service is well-functioning. Since an infrastructure’s invisibility cannot be rendered visible by a single agent, but has to be negotiated with several actors, this means that librarians need allies. In line with previous school library research, a main aspect of the participants’ accounts was experiences of being seen as invisible, while actively attempting to gain more visibility.

The aim of the present article was to discuss the constitution of the school library as an important infrastructure of a school site. This approach is valuable in understanding how different infrastructures are connected and work together at the site of the school. As an additional contribution, when using the concept of infrastructure to understand school libraries, we make school libraries visible as a vital part of the school site. This article addresses the autonomy and visibility of the school library as an infrastructure in relation to other infrastructures at the school site. As workers within an infrastructure, school librarians uphold a specific kind of position characterised, as several researchers have noted before, by a need for more visibility (cf, Ballard, 2008; Hartzell, 1997; Shaper and Streatfield, 2012; Todd, 2012).

In developing the use of the infrastructure concept, together with ideas from practice theory, the school site is seen as constituted by social practices and not solely by practices oriented towards learning. This conceptual switch creates opportunities for a wider range of strategic discussions concerning schools, education and learning than is currently the case. Nevertheless, by viewing school libraries as infrastructures for practices at schools it becomes possible to understand the institutional, organizational, social and material or technological arrangements of learning practices (cf. Guribye and Lindström, 2009).

The work enacted by school librarians is always connected to teaching and learning, and we have not yet focused specifically on library professionals when performing their work as resources for teaching and learning. Such a focus may contribute to their visibility and counter the well-documented underuse of school libraries as pedagogical resources (cf, Sheldon, Davis and Connolly, 2014). It is as part of the infrastructure of the school site and its structures and arrangements that librarians do their work and aim to become highly valued resources for teaching and learning. This would be an interesting topic for future studies.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted within the frame of the Linnaeus Centre for Research on Learning, Interaction and Mediated Communication in Contemporary Society (LinCS) at the University of Gothenburg and the University of Borås, Sweden (registration number: 349-2006-146).

About the authors

Ulrika Centerwall is a Doctoral Student at the Swedish School of Library and Information Science (SSLIS), University of Borås, and is also a member of the Linnaeus Centre for Research on Learning, Interaction and Mediated Communication in Contemporary Society (LinCS). She has a Master’s in Library and Information Science. She can be contacted at: ulrika.centerwall@hb.se

Jan Nolin is Professor at the Swedish School of Library and Information Science, University of Borås, Sweden. He received his PhD in the Theory of Science at Gothenburg University, Sweden. He can be contacted at: jan.nolin@hb.se

References

- American Association of School Librarians & Association for Educational Communications and Technology. (1998). Information power: building partnerships for learning. Chicago, IL: American Library Association.

- Alexandersson, M. & Limberg, L. (2012). Changing conditions for information use and learning in Swedish schools: a synthesis of research. Human IT, 11(2), 131-154. Retrieved from http://etjanst.hb.se/bhs/ith/2-11/mall.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6cT55Q2Y7)

- Ballard, S. (2008). What can teacher-librarians do to promote their work and the school library media program? Be visible, assess, and provide evidence. Teacher Librarian, 36(2), 22-23.

- Bonini, T., & Gandini, A. (2016). Invisible, solidary, unbranded and passionate: everyday life as a freelance and precarious worker in four Italian radio stations. Work organization, Labour and Globalisation, 10(2), 84-100.

- Bowker, G.C., Baker, K., Millerand, F. & Ribes, D. (2010). Toward information infrastructure studies: ways of knowing in a networked environment. In J. Hunsinger, L. Klastrup & M. Allen (Eds.), International handbook of Internet research (pp. 97-117). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

- Centerwall, U. (2019). Performing the school librarian: using the Butlerian concept of performativity in the analysis of school librarian identities. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 51(1), 137–149

- Church, A.P. (2008). The instructional role of the library media specialist as perceived by elementary school principals. School Library Media Research, 11(1), 1-35.

- Cooper, O.P. & Bray, M. (2011). School library media specialist-teacher collaboration: characteristics, challenges, opportunities. TechTrends, 55(4), 48-55.

- Denzin, N.K. (2001). The reflexive interview and a performative social science. Qualitative research, 1(1), 23-46.

- Edwards, P.N. (2003). Infrastructure and modernity: force, time, and social organization. In T.J. Misa, P. Brey and A. Feenberg (Eds.), The history of sociotechnical systems. Modernity and Technology (pp. 185-225). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

- Farmer, L.S. (2006). Library media program implementation and student achievement. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 38(1), 21-32.

- Gaver, M.V. (1963). Effectiveness of centralized libraries in elementary schools (2nd. ed.). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- Gretes, F. (2013). School library impact studies: a review of findings and guide to sources. Owings Mills, MD: Harry & Jeanette Weinberg Foundation.

- Guribye, F. (2005). Infrastructures for learning: ethnographic inquiries into the social and technical conditions of education and training. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) University of Bergen, Norway.

- Guribye, F. & Lindström, B. (2009). Infrastructures for learning and networked tools. The introduction of a new tool in an inter-organizational network. In L. Dirckink-Holmfeld, L. Jones & B. Lindström (Eds.), Analysing networked learning practices in higher education and continuing professional development, (pp. 103-116). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Gärdén, C. (2017). Skolbibliotekets roll för elevers lärande: en forsknings- och kunskapsöversikt år 2010-2015. [The role of the school library for pupil´s learning: a research- and knowledge review year 2010-2015]. Stockholm: Kungliga biblioteket.

- Hartzell, G. (1997). The invisible school librarian: why other educators are blind to your value. School library journal, 43(11), 24-29.

- Hartzell, G. (2002). Capitalizing on the school library's potential to positively affect student achievement: a sampling of resources for administrators. Knowledge Quest, 31(1; SUPP), 65-93.

- Huvila, I., Holmberg, K., Kronqvist-Berg, M., Nivakoski, O. & Widén, G. (2013). What is librarian 2.0 – new competences or interactive relations? A library professional viewpoint. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 45(3), 198–205.

- IFLA and UNESCO. (1999). School library manifesto. The Hague: International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. Retrieved from https://www.ifla.org/publications/iflaunesco-school-library-manifesto-1999. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74I9q63yc).

- Jewett, T. & Kling, R. (1991). The dynamics of computerization in a social science research team: a case study of infrastructure, strategies, and skills. Social Science Computer Review, 9(2), 246-275.

- Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P. & Bristol, L. (2014). Changing practices, changing education. Singapore: Springer.

- Lance, K.C. (2002). How school librarians leave no child behind: the impact of school library media programs on academic achievement of US public school students. School Libraries in Canada, 22(2), 3-6.

- Lance, K.C., Rodney, M.J. & Schwarz, B. (2010). The impact of school libraries on academic achievement: a research study based on responses from administrators in Idaho. School Library Monthly, 26(9), 14-17.

- Larkin, B. (2013). The politics and poetics of infrastructure. Annual Review of Anthropology, 42, 327-343.

- Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning. Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Lawton, A. (2015). The invisible librarian: a librarian's guide to increasing visibility and impact. Waltham, MA : Chandos Publishing, Elsevier

- Lewis, M. (2016). Professional learning facilitators in 1:1 program implementation: technology coaches or school librarians?. School Libraries Worldwide, 22(2), 13-23.

- Limberg, L. & Alexandersson, M. (2003). The school library as a space for learning. School Libraries Worldwide, 9(1), 1-15.

- Limberg, L. & Lundh, A.H. (2013a). Skolbibliotekets roller i förändrade landskap: en forskningsantologi. [The school library’s roles in changing landscapes: A research anthology]. Lund, Sweden: BTJ förlag.

- Limberg, L. & Lundh, A.H. (2013b). Vad kännetecknar ett skolbibliotek? [What characterises a school library?]. In: L. Limberg & A. Lundh (Eds.). Skolbibliotekets roller i förändrade landskap: en forskningsantologi [The school library’s roles in changing landscapes: a research anthology]. Lund, Sweden: BTJ förlag

- Lu, C., Chin-Chung, T. & Wu, D. (2015). The role of ICT infrastructure in its application to classrooms: a large scale survey for middle and primary schools in China. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 18(2), 249-261.

- Markless, S. & Streatfield, D. (2013) Evaluating the impact of your library. (2nd. ed.). London: Facet Publishing.

- Meyers, E.M., Nathan, L.P. & Saxton, M.L. (2007). Barriers to information seeking in school libraries: conflicts in perceptions and practice. Information research, 12(2), paper 295. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/12-2/paper295.html. (Archived by the Internet Archive at https://bit.ly/2Yt0BkJ)

- Ott, T. (2017). Mobile phones in school: from disturbing objects to infrastructure for learning. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Gothenburg University, Sweden. Retrieved from https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/53361/1/gupea_2077_53361_1.pdf

- Pilerot, O. (2014). Making design researchers' information sharing visible through material objects. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(10), 2006-2016.

- Pilerot, O. & Limberg, L. (2011) Information sharing as a means to reach collective understanding: a study of design scholars' information practices, Journal of Documentation, 67(2), 312-333

- Ribes, D. & Baker, K. (2007). Modes of social science engagement in community infrastructure design. In Steinfield, Pentland, Ackerman, and Contractor (Eds.), Communities and Technologies 2007: Proceedings of the Third Communities and Technologies Conference, Michigan State University, 2007, (pp. 107-130) London: Springer.

- Schatzki, T.R. (2002). The site of the social: a philosophical account of the constitution of social life and change. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Schatzki, T. (2010). Materiality and social life. Nature and Culture, 5(2), 123-149.

- Schultz-Jones, B.A. & Oberg, D. (Eds.) (2015). Global action on school library guidelines. Berlin: De Gruyter Saur.

- Shaper, S. & Streatfield, D. (2012). Invisible care? The role of librarians in caring for the ‘whole pupil’ in secondary schools. Pastoral Care in Education, 30(1), 65-75.

- Sheldon, S.B., Davis, M.H. & Connolly, F. (2014). A library they deserve: the Baltimore elementary and middle school library project. Baltimore, MD: Baltimore Education Research Consortium at John Hopkins University.

- Silverman, D. & Marvasti, A. (2008). Doing qualitative research: a comprehensive guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Skolinspektionen. (2011). Skolbiblioteket som pedagogisk resurs. [The school library as a pedagogical resource]. Retrieved from https://www.skolinspektionen.se/sv/Beslut-och-rapporter/Publikationer/Granskningsrapport/Kvalitetsgranskning/skolbiblioteket-som-pedagogisk-resurs/. (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/74IB5AvJv)

- Star, S.L. (1999). The ethnography of infrastructure. American Behavioral Scientist 43(3), 377-391.

- Star, S.L. & Ruhleder, K. (1996). Steps toward an ecology of infrastructure: design and access for large information spaces. Information Systems Research, 7(1), 111-134.

- Stevens, R., Jona, K., Penney, L., Champion, D., Ramey, K.E., Hilppö, J. & Penuel, W. (2016). FUSE: an alternative infrastructure for empowering learners in schools. Singapore: International Society of the Learning Sciences.

- Stratfield, D. & Markless, S. (1994). Invisible learning? The contribution of school libraries to teaching and learning. London: The British Library Research and Innovation Centre. (Library and Information Research Report 98)

- Sundin, O. (2015). Invisible search: information literacy in the Swedish curriculum for compulsory schools. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 9(4), 193-209.

- Sweden. Statutes. (2010). Skollag (2010:800). [School law (2010:800)] Stockholm: Department of Education.