Using classroom talk to understand children's search processes for tasks with different goals

Sophie Rutter, Paul D. Clough and Elaine G. Toms.

Introduction. This study provides insights into the talk (defined here as any verbal utterances issued during a search activity) that children (ages 10 and 11) engage in when finding information on the Internet for two teacher-assigned tasks with different search goals: a specific item task where the goal is to find particular information, and a general topical task where the goal is to find information on a topic but no specific information is looked for.

Method. Eight children were observed interacting with their teacher and fellow classmates while using search systems in their classroom.

Analysis. The talk captured in the classroom was analysed thematically and mapped onto an existing and established search process model.

Results. While talk differed for the three key search sub-processes, most noticeable was how talk varied according to search goal. Discussion occurred during the specific item task when children were finding it difficult whereas discussion in the general topical task led children to extend the task.

Conclusion. Children's search processes and the support they need are contingent on search goal. Recommendations are made to educators on how best to support children for the two key goal types.

Introduction

The need to educate and support children in their use of search systems is obvious: 'Students unable to navigate through a complex digital landscape will no longer be able to participate fully in economic, social and cultural life around them' (OECD, 2015, p. 17 ). Although researchers have responded to this concern by producing guidelines for educators, these guidelines tend to focus on supporting children doing research assignments rather than considering all the uses of search systems in school classrooms (Chu, Tse and Chow, 2011; Kuiper, Volman and Terwel, 2009; Nesset, 2013). As valuable as these guidelines are, they are not sufficient as it is likely that search tasks for research assignments have general topical goals (where the goal is to find information on a topic but no specific information is looked for); however, children also complete search tasks with specific item goals (where the goal is to find particular information) for other aspects of their school work (Rutter, 2017). While there are some studies that consider the impact of search tasks with different goals on children's search processes, these studies are usually conducted outside of children's normal educational contexts. In addition, children are commonly taken out of class and are asked to complete tasks designed for the purpose of the study, rather than tasks designed by school teachers (for example Borlund, 2016; Schacter, Chung and Dorr, 1998). We therefore do not know how children are using search systems for their school work, or the influence of the school environment. This is important, however, because to develop search systems that are more responsive to people's needs a good understanding of the environment within which information is used is required (Taylor, 1991).

Primary schools (equivalent to elementary schools in the US) are a key environment (home being another) within which children search and use information. In this study, we observe a primary school class (ages 10 and 11) searching the Internet for two teacher-assigned search tasks with different search goals (specific item and general topical). The research team had no input into the design of the lesson and the search tasks. Analysing verbal interactions within the classroom through talk (defined here as any verbal utterance), we examine how the class teacher and children support each other at the different points of the search process, and the similarities and differences between the two search task types. There is little research on children's talk during the search process and even less on how it varies according to type of task. This study contributes to our understanding of children's collaborative information seeking in the classroom environment. Based on the findings, recommendations are made to educators and search system designers.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows: in the following section, we review related work within areas such as supporting children in the classroom, the search process, and classroom talk. Then we present the two research questions addressed in this paper, followed by the methodology and the approaches we used to gather and analyse data. The next section provides the results of our studies and maps these to an existing model of the search process. We then discuss our results in relation to the past work and our research questions before providing recommendations and concluding the paper.

Literature review

First, we review what guidance researchers have produced for teachers, and how teachers support children in class. Then we review the importance of search task goal on the search process. Finally, we consider how classroom talk has been used in other studies.

Supporting children in the classroom

There have been a number of studies that have considered how primary-age (ages 4-11) children can be best supported when completing research assignments. These studies tend to focus on improving information literacy skills. Most notable of these are the studies by Kuiper, Volman and Terwel (2009), and Nesset (2013). Kuiper, et al. (2009) investigated whether children (ages 10 and 11) can acquire web literacy skills while undertaking a collaborative inquiry project. In three of the four classes they observed children did gain literacy skills, but many children also needed support and guidance. Most notably, children formulated research questions that were too broad and then had difficulty finding appropriate information.

More recently, Nesset (2013) developed two interconnected models of the research process that can be used to support primary-age children complete research assignments. The first model, PSU (Preparing, Searching and Using), is designed for instructors and older children. The second, BAT (Beginning, Acting and Telling) model is a simpler, more visual version designed for younger children. Building on earlier models by Kuhlthau (1991) and others, the PSU and BAT models were developed from a study of how children (ages 7-9) search for information, how they feel when doing so, and the barriers they face. Nesset (2013) found that there were three distinct stages (Preparing, Searching and Using) to completing research assignments, and within each of these stages there were distinct processes and feelings. So, for example, during the searching stage children must plan their search, define the task, then find, gather, evaluate and organise information. While doing this, children may feel happy, diverted, curious, irritated, disappointed, distracted or frustrated. Nesset (2013) also found that, although all three stages were important, the class received little instruction from the teacher for the searching stage.

These studies both provide valuable guidance on the support that children need when completing research assignments. However, because they have focused on the research assignment as a whole what is missing is an understanding of how different types of search task impact on the search process. Furthermore, in general there is a lack of understanding of what happens when children search for information in the school classroom. When researchers have examined the learning cycle the search activity is not actually examined, so it is a black box (Tanni and Sormunen, 2008), and even when researchers have studied children using search systems they have tended to conduct the studies outside the usual classroom (for example Borlund, 2016 ; Schacter, et al. 1998). It is also quite likely that teachers do not have a good understanding of how individual children within a class are using search systems. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, in a busy classroom the teacher does not have time to oversee each child individually (Hongisto and Sormunen, 2010; Rutter, Clough and Toms, 2019). Secondly, teachers often encourage children to collaborate in their information seeking. It has long been known that children learn better if their prior knowledge is activated and so often in the classroom teachers discuss the task topic before starting a search activity (de Vries, van der Meij and Lazonder, 2008). Then, partly because of a lack of resource in some schools, but also so children can support each other, teachers often arrange for children to search in pairs or small groups (Rutter, et al., 2019). At the end of the lesson, teachers then may encourage the class to share information with each other. This is partly so the teacher can check their understanding and also so that children who have been unsuccessful in their search are not penalized by not having any information. These common classroom practices mean that information is shared before, during and after searches, with teachers justifiably more concerned about children being able to use information than about them finding it (Nesset, 2013; Rutter, et al. 2019). However, that some children may not be able to use search systems is a concern, and is particularly problematic in the United Kingdom as it is rare for primary schools to have school librarians.

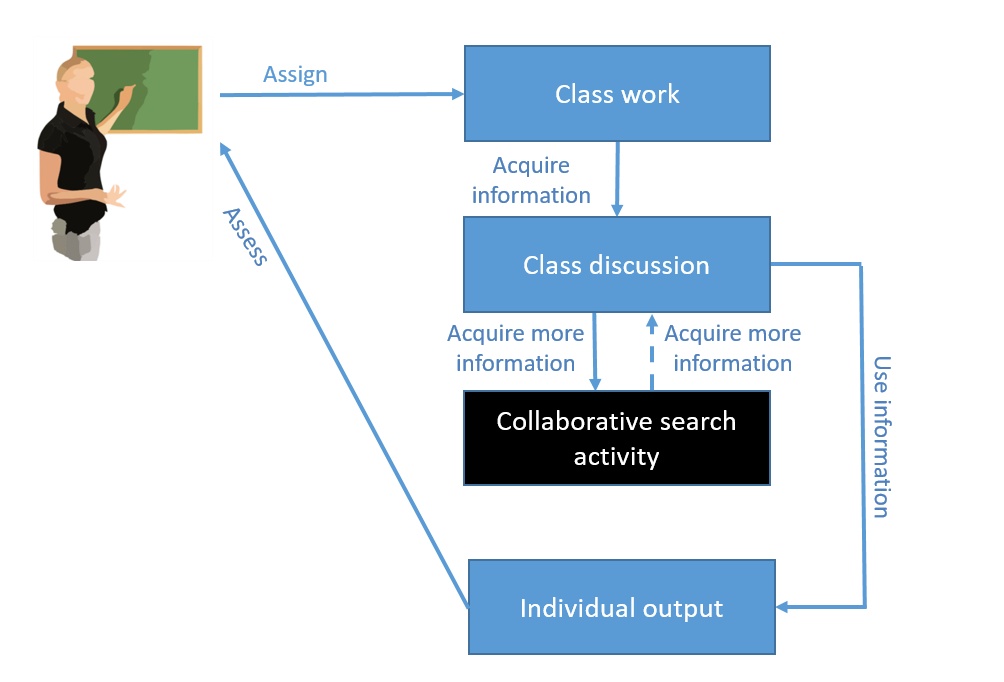

Figure 1: Search as a black box in the classroom

While there is a good understanding of the overall research process, with teachers supporting children to find and use information (and with researchers providing guidance to teachers), it is likely that teachers do not have a good understanding of how individual children are using search systems (see Figure 1). Furthermore, there is little guidance available for teachers as there is scant research on children using search systems within the classroom context.

Search task goal and search process

When children are searching for information in the school setting, what they should search for is often prescribed by their teacher. This statement of the information requirement can be considered a search task. While tasks have multiple characteristics (Li and Belkin, 2008), researchers often distinguish search tasks by goal (Kellar, Watters and Shepherd, 2007; Toms, 2011). There are essentially two key types of search goal, namely specific item and general topical. A specific item goal occurs when the searcher is looking for a particular item, and a general topical goal occurs when a searcher is looking for something (but not a particular something) on a particular subject (Toms, 2011).

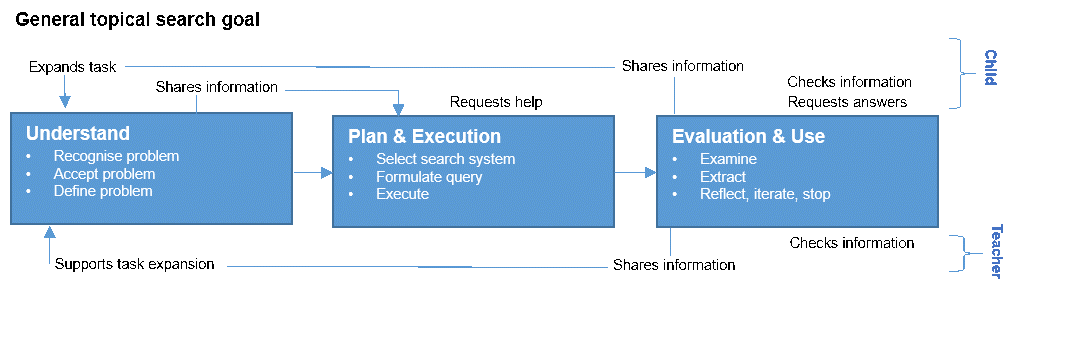

In general, the search process has been well documented. Notably Kuhlthau's (1991) information search process model indicates how search develops over a period of time, and the model describes thoughts, feelings and actions at the six different stages of the entire research process (initiation, selection, exploration, formulation, collection and presentation). By contrast, Marchionini's (1997) search process model explicitly describes interactions with search systems and is not particular to any specific stage of the research process. In Marchionini's (1997) model, there are three key sub-processes: understand (a need for information is recognised, accepted and defined), plan and execution (a resource is found, a query is formulated and executed, the results of the query are examined), and evaluation and use (information is examined and extracted until the information need is either satisfied or abandoned). Each of these sub-processes may be returned to as the search progresses. In this paper, we consider how the verbal interactions in the classroom relate to the key sub-processes identified by Marchionini (1997) for the two key types of search task.

Many studies have found that search goal influences search processes. Search tasks with specific goals are considered easier than those with general goals (Toms, 2011), particularly for children (Bilal, 2002; Schacter, et al. 1998). It is thought that when children are engaged in tasks with specific goals, they will know what they are looking for and will easily recognise information as relevant, whereas if the goal is less defined children cannot anticipate what it is they are looking for. Therefore, they will find it hard to express information needs, and will not know when information is relevant (Bilal, 2002; Schacter, et al. 1998). Nonetheless, it would be hasty to conclude that children will find search tasks with specific goals easier. While studies of search behaviour do indicate that goal accounts for differences in query formulation, results examination, time spent searching and navigation style within a study (Bilal, 2002; Borlund, 2016; Marchionini, 1989; Schacter, et al. 1998; Wu and Cai, 2016), across studies there is a lack of consistency in the pattern of search behaviour. This makes it difficult to either confirm or refute the expectations of how goal will influence children's search processes. A different approach to understanding how goal influences search process is required.

Classroom talk

For many studies of children's search processes the study takes place in a school but the researcher designs the study and children participate individually in the search (for example Bilal, 2002; Schacter, et al. 1998). Yet within the classroom, information seeking is often a shared activity (Knight and Mercer, 2014), even when children use search systems individually. There are, however, three notable studies that examine what takes place in the classroom, and in these studies class conversations are analysed to provide greater insight into children's search processes. When children (age 9) were doing research for a class project, Lundh (2010) analysed snippets of conversation between two children and their class teacher, and between two children and a librarian. It was found that although the children were told to research a topic of their own interest, what they actually looked for was 'constructed and negotiated in social interaction' with their peers, teacher and librarian. To understand students' experiences of inquiry-based learning, Hongisto and Sormunen (2010) analysed children's (age 14) requests for help and their teacher's responses. They found that most of the requests for help were regarding information seeking and use of sources. Other aspects of the assignment, such as planning and scheduling, required less support. Knight and Mercer (2014) examined how three groups of children (ages 11 and 12) collaborated when seeking information in class. They analysed each of the three groups for the type of talk (Disputational, Cumulative, Exploratory) and whether this led to different outcomes. They found that the groups that used Exploratory talk ('partners engage critically but constructively with each other's ideas') were more successful than those whose talk was Disputational (dismissive of others' ideas) or Cumulative (used information from others uncritically).

Our study builds on previous studies of classroom conversations by examining children's talk for two key task types (general topical and specific item) to reveal what support children need, and when, during the search process.

Research questions

Despite the collaborative nature of children's information seeking, children's search processes have primarily been analysed for an isolated individual rather than an individual within a group setting. Goal has been thought a critical factor in children's search, but the results of the different studies have been contradictory; a different approach may help to explain this. While there are a few studies of classroom talk, none of these have examined where classroom talk occurs in the search process, and whether talk differs depending on the search goal. The research questions for this study are (1) does classroom talk differ for the three key search sub-processes, and (2) does classroom talk differ depending on the search task goal? The research questions are answered by analysing what children say to each other and their teacher as they search for information. This is then mapped onto a search process model (Marchionini, 1997) to further analyse and illustrate what is happening.

Method

Research design

The study reported in this paper is part of a wider project that follows a naturalistic methodology, where children's real-life search is investigated (Rutter, 2017). This particular study is based on observations of children (ages 10 and 11) working in a school classroom. The search tasks were part of a planned lesson, and were prepared by the teacher, without any input from the research team. The class received no instruction from the researchers. Using this approach, it is possible to gain rich insights into children's contextual information behaviour.

The lesson

At the start of the lesson the teacher explained to the class that they were to search the Internet to find information about the Tour de France. The teacher displayed on the class interactive whiteboard the question 'There are different colour jerseys that the riders can win. What are they for?'. After approximately six minutes online some of the children told the teacher that they had found the answer. The teacher told the class that if they had finished (and only if they had finished) the Tour de France task they could find information on the World Cup. This task was given orally: 'Our country for the World Cup is Spain. I would like you to find out as much information about Spain and the World Cup as you can. So, I don't want to know about culture, I don't want to know about food. I don't want to know about the tourist industry. I want to know about the World Cup and Spain'. During the lesson, each child spent approximately 17 minutes online. The teacher spent the rest of the lesson de-briefing the class on the search activity.

Search task goal

The Tour de France task is an example of a specific item task in that it requires unambiguous answers that can be obtained from a single source. The World Cup task is an example of a general topical task, in that there is more than one appropriate answer and many information sources may be used. There are also other differences between the search tasks. Firstly, the search tasks were administered differently. However, although one child asked for the World Cup task to be repeated there is no other indication that receiving this task aurally accounted for any differences. Secondly, it might be that the World Cup task was of greater interest but both tasks were based on events likely to be interesting for the children: both were current events that had previously been discussed in the classroom and the Tour de France was shortly arriving in the local area.

Recruitment and participants

A purposive approach to sampling was taken whereby participants were selected because it was thought that they would best inform this study (Patton, 2015). A U.K. school known to the lead researcher was approached and agreed to participate in the research. The deputy head of the school discussed the research with teachers at the school and a teacher of Year 6 children (ages 10 and 11) agreed for the research to take place in their class. Morae screen recording software (http://www.techsmith.com/morae) was used as the main data collection instrument. When installing the equipment at the school it soon became apparent that no more than eight copies could run at any one time without impacting on the performance of the school network. For this reason, screen recordings were collected for eight children, but observations were still collected for the whole class, including browser history. Although studies of search process tend to have larger number of participants, this sample size is in keeping with other studies of classroom talk (Knight and Mercer, 2014; Lundh, 2010).

The study took place on Thursday 12th June 2014 during the afternoon. The school is a large primary school in a disadvantaged urban area. The quality of teaching is rated 'good' by Ofsted (the UK school inspection agency). The class consisted of twenty-five children, seated around three tables. The eight screen recording children were self-selecting (three from table 1, four from table 2, 1 from table 3). At the start of the class, computers installed with the screen recording software were put aside at the back of the class. The teacher briefed the children that they should select these computers if they were happy to have their searches screen recorded. More children wanted to have their searches recorded than there were computers available.

Data analysis

The data were analysed by mapping classroom talk onto an existing and commonly referenced model of the search process (Marchionini, 1997). This involved four steps.

Step 1: Transcription of screen and audio recordings

Each of the eight Morae video files were transcribed into a Word document. The transcripts were carefully prepared so that it would be possible to identify the recorded child's search interface actions (queries entered, results examined and websites visited), as well as what they were saying to whom while performing these actions. The teacher and screen recording children's voices could be clearly heard in the recordings. To protect the anonymity of these children they are quoted as Child 1, Child 2 through to Child 8. Wider classroom talk picked up in the screen recordings was also transcribed. Identifying these other children was harder, although to some extent this was possible by matching where they sat in class in relation to where the recorders were placed. Following the same pattern above these children are also quoted by number starting from Child 9. In the few cases where talk could not be clearly identified as coming from a particular child, a new child number was used.

Step 2: Code development

Four sets of codes were used to analyse the transcripts: (1) who was talking to whom, (2) which task was being completed, (3) where children were in the search process, (4) what was being said. The first three sets of codes required little or no development. Children either spoke to each other and / or to their teacher. The tasks were identified from the teacher's instruction, and which task each child was completing could be identified from classroom talk and / or the search interface. The third set of codes were taken from Marchionini's (1997) search process model. The fourth set of codes (what was being said) were derived inductively and developed over several iterations. Using open coding the explicit meaning of what each individual was saying was identified by taking a semantic approach whereby the analysis is in 'the explicit or surface meanings of the data and the analysis is not looking for anything beyond what a participant has said or what has been written' (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.84). Conversation analysis was not used as this type of analysis focuses more specifically on how phrases (such as 'I don't know') lead to action (Rapley, 2007) rather than the different topics of conversation. The initial open codes were then aggregated into different themes: a 'level of patterned response or meaning within the data set' (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p.10). Whether the themes as a whole were a good representation of the children's and teachers talk was also considered. Table 1 lists the different codes and provides illustrative examples of classroom talk.

| Code | Definition | Example classroom talk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child | |||

| Assesses task | Comments on how easy or difficult the task is | That was kind of easy. | |

| Checks information | Asks someone whether the information they have found is correct | Is yellow first? | |

| Requests answers | Asks someone for information to answer the task | What's that one? | |

| Requests help | Asks someone for help with the search process | What shall I type in? | |

| Shares information | Gives someone else information. This can be un-proffered or in response to a request | I know one that is much more expensive than that. | |

| Won't share information | Will not give someone information in response to a request | You can't copy mine, you know. Stop copying. | |

| Teacher | |||

| Supports | Key word selection | Helps with choosing terms to use in query formulation | So why don't you give me some keywords ... what would you look for? |

| Source selection | Helps with choosing search engine / search site | Do an image search. It's bound to give you pictures of different jerseys isn't it? | |

| Results selection | Helps with choosing which websites to visit from the search results | (Teacher selects websites from search results) | |

| Information extraction | Helps with identifying information either within the search results or websites | Right, can you see any other colour jerseys? | |

| Problem definition | Explains the task either by repeating or rephrasing the task statement | So you need to work out what that is for. | |

| Task expansion | Suggests looking for information that is in addition to the information requirements stated in task statement | Spain is part of the World Cup, so you'd be thinking players, you'd be thinking past success … | |

| Checks | Information | Checks that the right information has been found | Does it definitely mean that? Does the green jersey mean you are in second place? |

| Answer complete | Checks that all the information requirements in the task statement have been satisfied | That's it? You just found yellow jerseys? | |

| Ensures independent work | Checks that information is acquired using search systems and not from other people. May check with individual or make a general statement to class | I don't want you to share anything. | |

| Shares information | Gives an answer or additional information | If you cycle along in a yellow jersey everyone is like WOW, look at him, he's got the yellow jersey. | |

| Schedules tasks | Gives new tasks and ensures that the tasks are completed in the correct order | Only do the Spain thing if you've answered the original question. | |

Step 3: Applying and testing the coding scheme

Whether the four coding schemes could be reliably applied to the data was tested. Applying the first two sets of codes was straightforward. However, determining the units of analysis for the 'search process' and 'what is being said' coding schemes was difficult. Firstly, classroom talk is not linear; people talk across one another and talk in non-sequiturs. Secondly, as we wished to contextualise talk to the search process, the transcripts contained both talk and actions. As inter-coder reliability is dependent on the same code being applied to the same text by more than one coder, this was problematic. Inspired by Campbell, Quincy, Osserman and Pederson (2013), the lead researcher identified the units of analysis by dividing each transcript into 'units of meaning'. The lead researcher then applied all four code sets. As the first three sets of codes required little or no development, a second researcher checked the application of these codes in one transcript. For the fourth set of codes (what is being said), again following the advice of Campbell, et al. (2013), in one of the transcripts the code was replaced with a bracket and the second researcher then re-coded the bracketed section. The same code was applied by both researchers for 47 out of 53 codes (89% reliability). The code definitions were then refined until agreement was reached. To explain this further, this process is illustrated with an extract from one of the coded transcripts (Table 2). In this extract, the teacher has just briefed the class on the Tour de France task. Child 1 and Child 10, who are sitting next to each other at one of the three tables, are requesting help from the teacher.

| What is being said | Search process codes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | Teacher | Current sub-process | Transitions to | |

| TOUR DE FRANCE TASK | ||||

| CHILD 10: 'I don't get it. I don't get it.' TEACHER TO TABLE 1: 'How do you search? How do you find things out? Where do you go?' ACTION: Opens Google. CHILD 10: 'Google.' TEACHER TO TABLE 1: 'He says Google. Google it then.' ACTION: Opens two tabs. Closes second tab. |

Requests help | Supports: Source selection | Understand: Define problem | Plan & Execution: Select search system |

| CHILD 1: 'What shall I type in? What shall I type in? [Pause]. What shall I type in [Teacher]?' TEACHER TO TABLE 1: 'You guys you…' CHILD 1: 'Shall I copy off here?' TEACHER TO TABLE 1: '…need to find out what the different colour jerseys mean in Tour de France, right, so why don't you give me some keywords...' CHILD 1: 'I'm stuck.' TEACHER TO TABLE 1: '...and I'll write them down. [Pause]. What would you look for? [Pause]. What would you type into Google? [Children's responses not picked up in audio recording]. Good, I'll leave you alone. You know what to do.' CHILD 10: 'Do you need to write Tour de France?' TEACHER: 'You could do. You could put Tour de France. Type that in see what you get.' CHILD 10: '[Teacher], it's just come up with that.' TEACHER: 'You must have put something in that it didn't like. |

Requests help | Supports: Problem definition Supports: Keyword selection |

Plan & Execution: Formulate query | Plan & Execution: Formulate query |

Step 4: Mapping onto the search process model

For each of the search tasks the classroom talk was aggregated and mapped onto Marchionini's (1997) search process model (see Figures 2 and 3). It should be noted that we have made a minor amendment to the model: Marchionini (1997) has examine resultsat plan and execution and examine information at evaluation and use. As today so much information is included in the result descriptions and information boxes on the search results page it was difficult to distinguish between examine results and examine information in our data set. For this reason, we consider examine at evaluation and use only.

Ethics

An ethics application was submitted to, and approved by, the University of Sheffield Ethics Committee. The research was discussed with staff at the school. Consideration was given to the potential harm in conducting the research and the need for children to fully understand the nature of the research. A letter detailing the research was sent home with all the class children, and the children were further briefed about the research on the day of data collection. No child, or parent/carer representative of a child, declined to take part in the research. After the study was completed a report including recommendations was sent back to the school.

Results

The following text describes what was said during the different parts of the search process for the two tasks (specific item and general topical). It is then illustrated using Marchionini's (1997) model.

It is only during the Tour de France (specific item) task that children assess the task, and they do this at all three key search sub-processes. This assessment occurs for children who are finding the task easy, as well as those finding it hard.

Child 4: I was rubbish at it, Sir. [Pause]. I can't do it.

Child 9: That was easy. 'Tour de France 101 - What do the different colour jerseys mean?' [reading name of website and strapline off the screen] That was kind of easy.

Those children assessing this task as difficult ask the teacher for help with the search. The teacher helps the children Plan & Execute the search by facilitating source selection and query formulation. None of the class ask for help while completing the World Cup (general topical) task.

Child 3: [Teacher] it's just come up with that.

Teacher: Do an images search. It's going to give you pictures of different jerseys isn't it?

Child 1: What shall I type in?

Teacher: So why don't you give me some keywords. I'll write them down and you can type them in.

Overall, many of the children's requests for help at Plan & Execution are unheeded as the teacher spends more time helping children with other parts of the search process. For both tasks, but particularly for the World Cup task, much of the talk from both the teacher and children is around Evaluation & Use. For both tasks during this sub-process the teacher checks that they have understood what they find and that the information is correct. Children also check with each other.

Child 12: I know what white means. Do you know what white means?

Child 8: 'Fastest overall rider' [reading off screen].

Child 12: Yeah, it is.

Teacher: I've just heard someone say is green second place. [Is that] right?

Child 8: Green is the sprinter's jersey.

Teacher to table 3: Most famous player?

Child 14: Most famous – Iniesta. He won the world.

Child 15: That geezer's right good.

Teacher: Iniesta?

Child 14: Yeah he's a right player.

Child 15: He's the one that won Spain the World Cup. He scored the winning goal.

Child 14: He's a right player.

Teacher: There must be a Spanish player that I've heard of?

Child 14: Jesus, Jesus Nobus.

Child 15: Sergio Lawrence.

Classroom talk at Evaluation & Use often leads back to Understand. However, how and why this happens is different for both tasks. For the Tour de France task, the teacher directs children back to Understand because the task problem has not been fully understood. The teacher does this by further defining the task, initially by repeating the task statement, and later by breaking the problem into manageable parts.

Teacher: You have to answer that question; there are different colours jerseys that riders can wear. What are they for?

Teacher to Child 10: So you've got 'Tour de France', so maybe [add] 'jersey' [to the query]. [Pause] Well done. So you've got white. That's cool. The spotty one. There's green and yellow. So you need to work out what that is for? What's that one for? Do you know? It's yellow. Go on then, what does the yellow jersey mean?

By contrast, for the World Cup task the ensuing discussion leads to an expansion of the task, which then gives the children other areas of the topic to pursue. As the children discuss their findings with each other this then links into query formulation. During the following classroom talk Child 14, Child 15, Child 16 and Child 17 all enter queries based on variations of the 'most expensive player in Spain'.

Child 14: I know who the most expensive player is in Spain.

Child 15: Who?

Child 14: Iniesta.

Child 15: How did you find that out?

Child 16: No, Sergio Ramos.

However, in both tasks not all of the talk at Evaluation & Use leads back to Understand as some information is shared and nothing further happens. Furthermore, in the Tour de France task children request information from each other and if the answer is shared this leads to the stopping of the task as it is considered complete. Notably, the teacher does not want the children to share information on the Tour de France.

Child 19: What's that one?

Child 2: King of the Mountains.

Teacher to Child 20: That's not really using the Internet if you are asking someone else on the table

Task scheduling also differs for the two tasks. At the start of the lesson only the Tour de France task is given. When some of the class have found answers they immediately stop searching. The teacher then orally gives the World Cup task. Many children swap to this task, despite the teacher instructing that the original task must be completed first. Some children also stop the Tour de France task early and conduct their own personal searches.

Teacher: How are we getting on?

Child 6: I've wrote down footy names.

Teacher: Where is the answer to the original question? That's interesting. Is that the answer to the original question? Yellow jerseys. Is that it? You just found yellow jerseys. So there are different colour jerseys, that the riders can win. What are they for? And you've put yellow jerseys and then started to talk about football. You've got 30 seconds. Do something about it.

Child 1 [submits query 'pool cat']: Look! [Much laughter].

Child 3: Pool cat.

Child 1 [submits query 'pole cat']: What are these? They don't grow big. [Later in the lesson both Child 1 and Child 3 submit more polecat queries].

By contrast to the Tour de France task, after finding information about the World Cup additional information is searched for.

We now illustrate in Figures 2 and 3 what children and teachers are saying to each other at the different stages of the search process for the two tasks, and how children transition between the sub-processes. In these figures, what the children are saying to each other and their teacher is shown in the top half of the model, and the talk that the teacher either initiates or responds to is shown in the bottom half. If classroom talk leads to a transition from one part of the search process to another this is illustrated with an arrowed line. In this way, we show all the transitions between sub-processes and all instances of classroom talk at each sub-process regardless of frequency. It should therefore be noted that this diagram indicates where classroom talk occurs but not the amount of talk.

Discussion

Figures 2 and 3 clearly illustrate that classroom talk is different for the key search sub-processes and the two task types. We discuss these differences next incorporating the relevant research literature.Research question 1: does classroom talk differ for the three key search sub-processes?

Classroom talk differed depending on the search sub-process. For both tasks most of the classroom talk is at the sub-process evaluation and use. It is through the information children have extracted at this sub-process that the teacher checks understanding of the task. Similarly, it is at evaluation and use that children share and check information with each other. While the teacher offers considerable support to children both at understand and evaluation and use for both tasks, comparatively little help (in terms of the amount of talk as opposed to the aggregated occurrence as indicated in Figures 2 and 3) is offered at plan and execution, despite children's requests. As Nesset (2013) found, children need more support during the search process, particularly with defining their searches.

Research question 2: does classroom talk differ depending on the search task goal?

Although as described above classroom talk did differ depending on the search sub-process, it is search task goal that accounts for most of the observed differences, and this is reflected in Figures 2 and 3. In the specific item task (Figure 2) much more support is needed, but in the general topical task (Figure 3) there is much more sharing of information.

When carrying out the general topical task (World Cup) children did not assess the task. By contrast with the specific item (Tour de France) task they did do this and children's opinions varied as to how easy / difficult it was. That children experienced the same tasks quite differently could explain why when analysing data quantitatively there is a lack of consistency in the pattern of search behaviour across studies (Bilal, 2002; Borlund, 2016; Marchionini, 1989; Schacter, et al. 1998; Wu and Cai, 2016). For some children it is perhaps the rigidity of this task that makes it difficult rather than it being easy to look for a particular answer (Bilal, 2002; Schacter, et al. 1998). By contrast, the flexibility of the general topical task, which is less structured and more open to interpretation, makes it easier for all children to find some information. However, it should be remembered that these tasks were designed by the teacher and that children may have difficulty designing their own general topical tasks (Kuiper, et al. 2009). Furthermore, studies of secondary school children have shown that to formulate meaningful questions children need to be able to find a focus (Kuhlthau, 2004; Cole, Beheshti, Large, Lamoureux and Abuhimed, 2013); this is generally not well supported by teachers (Limberg, Alexandersson, Lantz-Andersson, and Folkesson, 2008; Sormunen and Alamettälä, 2014; Alamettälä and Sormunen, 2018) and was not observed in this study either.

Notably for both tasks, although the children were nominally working individually to search the Internet, they not only conferred but also used each other as information sources. We note that the general topical task generated much more discussion and sharing of information that led back to problem definition and expanding the task into different topic areas (see Figure 2). As Lundh (2010, n.p.) found, what the children looked for in the general topical task was 'constructed and negotiated in social interaction' with peers and the teacher. This was not the case for the specific item task where there were particular answers that must be found. With the general topical task, the children shared and built upon their understanding of the information they found in the task much more so than they did for the specific item task. The exploratory talk that Knight and Mercer (2014) found so crucial to success only occurred during the general topical task, whereas in the specific item task more of the talk was procedural with children who are struggling with the task requesting help.

Recommendations

As evidenced by the classroom talk, the search process differed for the two task types. When using search systems in the classroom it may be helpful for educators to think about the goal of the search task and the effect this has on information seeking. The following recommendations are made to educators:

Recommendation 1: For children to become proficient searchers it is important that they have practice at searching information for both specific item and general topical search tasks. To develop appropriate search strategies children should be taught the requirements and constraints of each task type.

Recommendation 2: The level of support children need is likely to vary for the specific item search task, and this should be taken into account when planning a search activity. For some children, a specific item search task is hard and the teacher may need to give considerable support. Other children may find the task easier and quickly finish the task. To make the task more challenging for those children, they could be asked to (1) find more than one source for the information, and evaluate the different sources, and (2) find alternative wordings for queries, including finding the fewest number of words needed for a query that still returns the answer.

Recommendation 3: A general topical search task may lead to more diverse information acquisition, and this type of task is more likely to result in children discussing (unprompted by the teacher) the information they find with each other. This in turn may motivate further information-seeking and could help children to select and focus on an aspect of a topic that they find personally interesting.

Recommendation 4: Particularly for specific item tasks where there is less flexibility in the information requirements, determining whether children have understood what information they need before they start searching may benefit struggling searchers and reduce the need for support at the planning and execution stage.

The following recommendation is made to search system designers:

Recommendation 5: While teachers can support the whole class in their understanding of tasks and use of information, it is difficult in a busy classroom for teachers to oversee individual children executing searches. It is perhaps here using a task-based approach to user modelling (Mehrotra & Yilmaz, 2015) that search systems could do more to support children.

Limitations and future work

In this study we examined classroom talk for two tasks within a single classroom setting. While this detailed level of analysis reveals the influence of the class setting and the children's individual experiences of the two tasks with different goals, it is recognised that additional research is required before the universality of the findings can be realised. However, this study adds to and complements studies of how goal influences children's search processes (Bilal, 2002; Borlund, 2016; Marchionini, 1989; Schacter, et al. 1998; Wu and Cai, 2016) and the teacher's pedagogical approach, particularly for the general topical task, is similar to that reported in other studies (Limberg, et al. 2008; Sormunen and Alamettälä, 2014; Alamettälä and Sormunen, 2018). A further limitation is that while a classroom study has high ecological validity, the class completed the tasks in the same order and so t is not possible to determine what learning effects if any there could be between the two tasks.

Conclusions

This paper describes a study into how primary school children (ages 10 and 11) search within a classroom setting. We identify verbal utterances (or talk) that occur during the search process and compare specific item tasks with general topical. For both tasks, through classroom talk children and teachers supported each other in the search process at understand and evaluation and use. However, many of the children's requests for help went unheeded at plan and execution. Classroom talk also differed depending on the search task goal suggesting that children experience the two types of task differently and that the kind of support needed to use search systems effectively is contingent on goal.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the school and children who kindly participated in this study. This research was conducted as part of a PhD, funded by a University of Sheffield Faculty Scholarship.

About the authors

Sophie Rutter has been recently appointed lecturer in Information Management in the Information School at the University of Sheffield, UK. Her research interests are in children's information seeking and how the environment influences the way people interact with technology. She can be contacted at s.rutter@sheffield.ac.uk

Paul D. Clough is Data Scientist at Peak Indicators and also holds the position Professor of Search and Analytics in the Information School at the University of Sheffield, UK. His research interests mainly revolve around developing approaches to assist people with accessing, managing, analysing and using data and information. Paul can be contacted at p.d.clough@sheffield.ac.uk.

Elaine G. Toms is Professor of Information Innovation & Management in the Management School at the University of Sheffield, UK. Her current research focuses on how task shapes (or should shape) the information tools we used, the dilemma of serendipity in the face of technological advancement, and the evaluation of information systems. Elaine can be contacted at e.toms@sheffield.ac.uk

References

- Alamettälä, T. & Sormunen, E. (2018). Lower secondary school teachers' experiences of developing inquiry-based approaches in information literacy instruction. In S. Kurbanoğlu, J. Boustany, S. Špiranec, E. Grassian, D. Mizrachi & L. Roy (Eds.), Proceedings European Conference on Information Literacy (ECIL 2017), (pp. 683–692). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. (Communications in Computer and Information Science, 810),

- Bilal, D. (2002). Perspectives on children's navigation of the world wide web: does the type of search task make a difference? Online Information Review, 26(2), 108-117.

- Borlund, P. (2016). Framing of different types of information need within simulated work task situations: An empirical study in the school context. Journal of Information Science, 42(3), 313-323.

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

- Campbell, J. L., Quincy, C., Osserman, J. & Pederson, O.K. (2013). Coding in-depth semi structured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociological Methods and Research, 42(3), 294-320.

- Chu, S.K.W., Tse, S.K. & Chow, K. (2011). Using collaborative teaching and inquiry project-based learning to help primary school students develop information literacy and information skills. Library & Information Science Research, 33(2), 132-143.

- Cole, C., Behesthi, J., Large, A., Lamoureux, I., Abuhimed, D. & AlGhamdi, M. (2013). Seeking information for a middle school history project: the concept of implicit knowledge in the students' transition from Kuhlthau's Stage 3 to Stage 4. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(3), 558-573.

- de Vries, B., van der Meij, H. & Lazonder, A. W. (2008). Supporting reflective web searching in elementary schools. Computers in Human Behaviour, 24(3), 649-665.

- Hongisto, H. & Sormunen, E. (2010). The challenges of the first research paper: observing students and the teacher in the secondary school classroom. In Lloyd, A. & Talja, S. (Eds.) Practising Information Literacy: Bringing theories of learning, practice and information literacy together, (pp. 95-120). Wagga Wagga, NSW: Centre for Information Studies.

- Kellar, M., Watters, C. & Shepherd, M. (2007). A goal-based classification of web information tasks. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 43(1), 1-22.

- Knight, S. & Mercer, N. (2014). The role of exploratory talk in classroom search engine tasks. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 24(3), 303-319.

- Kuhlthau, C.C. (1991). Inside the search process: information seeking from the user's perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(5), 361-371.

- Kuhlthau, C. C. (2004). Seeking meaning: a process approach to library and information services. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

- Kuiper, E., Volman, M. & Terwel, J. (2009). Developing web literacy in collaborative inquiry activities. Computers & Education, 52(3), 668-680.

- Li, Y. & Belkin, N. J. (2008). A faceted approach to conceptualising tasks in information seeking. Information Processing and Management, 44(6), 1822-1837.

- Limberg, L., Alexandersson, M., Lantz-Andersson, A. & Folkesson, L. (2008). What matters? Shaping meaningful learning through teaching information literacy. Libri, 58(2), 82–91.

- Lundh, A. (2010). Studying information needs as question-negotiations in an educational context: a methodological comment. Information Research, 15(4). paper Colis 722 Retrieved from http://www.informationr.net/ir/15-4/colis722.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76qQmb9WA)

- Marchionini, G. (1989). Information-seeking strategies of novices using a full-text electronic encyclopedia. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 40(1), 54-66.

- Marchionini, G. (1997). Information seeking in electronic environments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mehrotra, R. & Yilmaz, E. (2015, September). Terms, topics & tasks: Enhanced user modelling for better personalization. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on The Theory of Information Retrieval (pp. 131-140). ACM.

- Nesset, V. (2013). Two representations of the research process: the preparing, searching, and using (PSU) and the beginning, acting and telling (BAT) models. Library and Information Science Research, 35(2), 97-106.

- OECD. (2015). Students, computers and learning: making the connection. Paris: OECD. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/publications/students-computers-and-learning-9789264239555-en.htm (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/73GFMhstI)

- Patton, Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. (4th ed.). London: Sage Publications.

- Rapley, T. (2007). Qualitative research kit: doing conversation, discourse and document analysis. London: Sage Publications.

- Rutter, S., Clough, P.D. & Toms, E.G. (2019). How the information use environment influences search activities: a case of English primary schools. Journal of Documentation, 75(2), 435-455.

- Rutter, S. (2017). Activities and tasks: a case of search in the primary school information use environment (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK. Retrieved from http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/19066/1/SR%20thesis%2027%20Nov%202017.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/76TIEaT68)

- , J., Chung, G. & Dorr, A. (1998). Children's internet searching on complex problems: performance and process analyses. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 49(9), 840-849.

- Sormunen, E. & Alamettälä, T. (2014). Guiding students in collaborative writing of Wikipedia articles – how to get beyond the black box practice. In Proceedings of EdMedia 2014 – World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications, 1, (pp. 2122-2130). Morgantown, WV: AACE.

- Tanni, M. & Sormunen, E. (2008). A critical review of research on information behaviour in assigned learning tasks. Journal of Documentation, 64(6), 893-914.

- Taylor, R. (1991). Information use environments. In Dervin, B. & Voigt, M., Progress in Communication Sciences, 10, 217-255.

- Toms, E. G. (2011). Task based information searching and retrieval. In I. Ruthven & D. Kelly (Eds.), Interactive information seeking, behaviour and retrieval. (pp. 43-59). London: Facet Publishing.

- Wu, D. & Cai, W. (2016). Empirical study on Chinese adolescents' web search behaviour. Journal of Documentation, 72(3), 435-453.