The information mapping board game: a collaborative investigation of asylum seekers and refugees’ information practices in England, UK

Kahina Le Louvier and Perla Innocenti

Introduction.This paper discusses the use of an information mapping board game for collaboratively identifying information practices of a small group of asylum seekers and refugees in the North East of England, UK.

Methods. Drawing on participatory visual methods, an original information mapping board game was designed.

Analysis. Qualitative results are discussed and analysed using grounded theory, constant comparative analysis, and situational mapping.

Results. The use of an information mapping board game allows participants going through the asylum process to become actively involved in mapping and sharing their own information practices, sources and barriers within a playful collaborative environment. It enables participants to become aware of their acquired information literacy by sharing knowledge, and to adapt the game to reflect their needs and knowledge.

Conclusion. This study indicates that participatory techniques such as the information mapping board game have the potential to engage hard to reach populations in the research process, to foster their agency, confidence, and capacities, and to inform actions at a local level.

Introduction

This paper discusses the use of the information mapping board game in research involving refugees and asylum seekers. This novel technique was designed as part of a pilot study investigating the information practices of applicants going through the asylum process in the North East of England, UK.

From the Brexit campaign to the implementation of ‘hostile environment’ policies (Kirkup and Winnett, 2012), the hospitality crisis in the United Kingdom led to a need to rethink the social inclusion of refugees in the British context. In the field of Library and Information Science, social inclusion has been defined as an information problem (Caidi and Allard, 2005), whereby migrants and refugees in particular are confronted with a ‘fractured information landscape’ (Lloyd, 2017) that prevents them from taking an active part in society. A number of studies have sought means to foster inclusion by identifying the information practices of refugees in Australia (Lloyd, 2014), Canada (Quirke, 2012), Sweden (Lloyd, Pilerot and Hultgren, 2017) and more recently Scotland (Oduntan and Ruthven, 2017). This pilot study brings this investigation to England with two aims:

- Draw an initial overview of the information landscape experienced by people who have been resettled in North East England as part of the asylum dispersal programme.

- Allow those who experienced the UK asylum process to exercise their agency and share their own information practices by experimenting with participatory methods via the vehicle of an information mapping board game.

Literature review

In information science, social inclusion is defined as an information problem (Caidi and Allard, 2005): without the capacity to access and make sense of information, newcomers cannot play an active part in society. Consequently, social inclusion requires understanding how migrants interact with information. Various studies have sought to identify the information practices of refugees, highlighting the following needs:

- Digital technology (Alam and Imran, 2015; Gifford and Wilding, 2013; Díaz Andrade and Doolin, 2016).

- Health information (Allen, Matthew and Boland, 2004).

- Compliance information, such as societal rules, policies, asylum refusal, legal rights and representation (Kennan, Lloyd, Qayyum and Thompson, 2011; Oduntan and Ruthven, 2017; Lloyd et al., 2017).

- Everyday information, such as education, employment, health, daily living, communication with family and friends, language, social life and leisure activities (Kennan et al., 2011; Oduntan and Ruthven, 2017; Lloyd et al., 2017; Quirke, 2015).

Studies identified interpersonal interactions as the preferred sources of information for most refugees (see Olden, 1999; Kennan et al., 2011; Shankar et al., 2016). These include interactions with friends and family (Quirke, 2012; Lloyd et al., 2017; Oduntan and Ruthven, 2017), or service providers, caseworkers and volunteers (Kennan et al., 2011; Quirke, 2012; Lloyd et al., 2017; Oduntan and Ruthven, 2017; Qayyum, Thompson, Kennan and Lloyd, 2014). Further information sources include digital sites such as social media (Lloyd and Wilkinson, 2016; Lloyd et al., 2017), leisure activities (Quirke, 2015; Lloyd and Wilkinson, 2016) and libraries (Varheim, 2014). These sites are described as information grounds (see Pettigrew, 1999) that facilitate the spontaneous exchange of information and the building of social capital through which refugees acquire information literacy (Varheim, 2014; Quirke, 2015; Lloyd and Wilkinson, 2016; Lloyd et al., 2017). They also allow newcomers to develop collective coping strategies such as information pooling (Lloyd, 2014; Lloyd, 2015; Lloyd et al., 2017).

The pilot contributes to such body of work by using an original technique that allow participants to express and map their own information practices.

Method

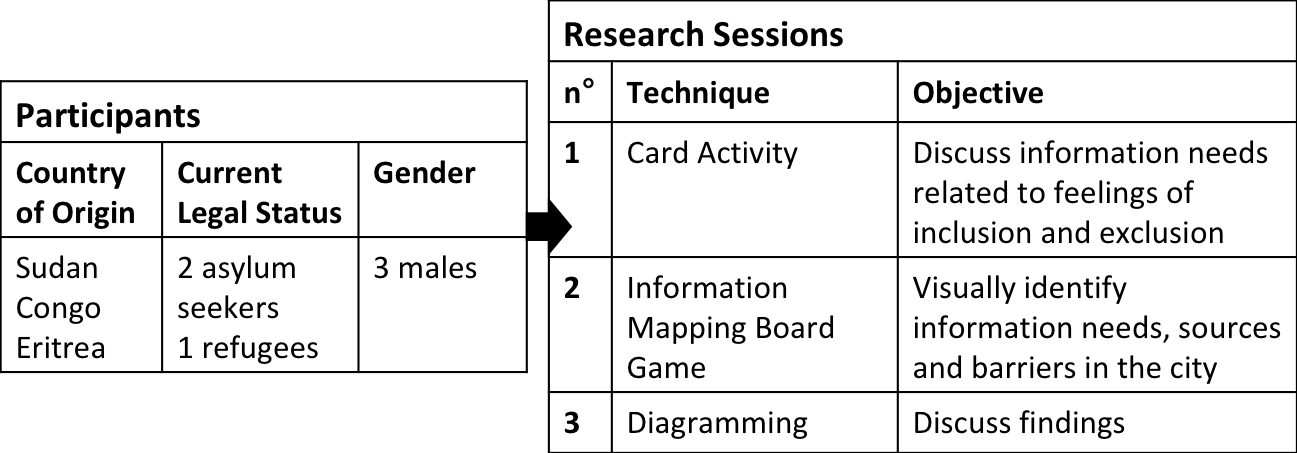

The pilot study used three focus groups employing qualitative participatory action research (Kindon, Pain and Kesby, 2007) to identify the information practices of refugees and asylum seekers settled in a city of the North East of England (Fig.1). This approach addresses the ethical implications of researching marginalised groups whose agency is often denied. Although participation was limited to a collaborative mode (Biggs, 1989), whereby the researcher designed the research questions and activities, the aim was to experiment on research techniques that are non-coercive, provide mutual benefits and allow participants to reflect on how to improve their situation. Participatory approaches are increasingly used in Library and Information Science research for they allow socially excluded groups to have their voice heard (Hicks and Lloyd, 2018), however they rely on a high level of participant engagement. Moreover, asylum seekers include people with diverse English language skills and education, precluding the use of traditional research methods. Visual methods such as photovoice have been suggested as powerful alternatives as they allow mitigation of language and literacy levels, and give participants an opportunity to be in control of the information they provide (Hicks and Lloyd, 2018). While the use of photovoice was considered for this pilot, it was judged as too time-consuming for participants.

Figure 1: Research design

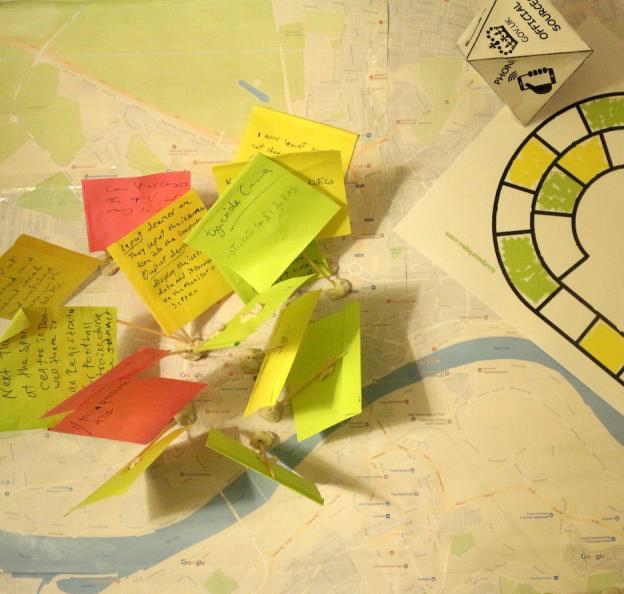

Another visual method was needed to investigate information practices, respecting participatory principles whilst adapting to the players. The information mapping board game was thus designed and composed of five different elements: a detailed street map of the urban area, a progression board, an eight-sided dice, green, yellow and pink flags, and coloured pieces (Fig.2). At the beginning of the game, each player placed their piece on the progression board. The colour of the square on which their piece stood determined their possible actions:

- Yellow – Players indicate a type of information they need in their everyday life and the source of information used to seek it on a yellow flag, and place it on the map.

- Green – Players indicate a type of information they share in their everyday life and the medium they used to share it on a green flag, and place it on the map.

- White – Players throw a die showing different information media (radio, official sources, printed media, TV, computer, phone, people and observation). They indicate information they either seek or share using the medium visible on the appropriate flag and place it on the map.

- Pink – After each turn, players can put a pink obstacle flag next to the flag just placed to indicate a barrier to that information activity.

Figure 2: Information Mapping Board Game: Progression board, information sources die, city map.

Each action was explained and discussed with the participants. Players moved two squares forward for each green and yellow flag they placed, one square forward for a pink flag, and one square backward when being stopped. The session lasted about two hours; participants had to leave before anybody won. The competing and playful nature of the game meant that participants joked whilst arguing their case. It may be considered that this game did not facilitate a deep investigation of each information activity. However, the rules of the game, as well as the possibility to break them, promoted insightful data capture, enabling participants to become aware of their capacities.

Data was analysed during the session with a grounded theory method and between each session using constant comparative analysis (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). At the end of the three sessions situational mapping (Clarke, 2005) was used to account for the complexities of participants’ situation, highlighting both the structure in which they are immersed and the way they experience it.

Findings and discussion

This original information mapping board game was designed to address three identified challenges:

- Mutual benefits. The game provided a space for participants to practice English in a friendly and non-judgmental environment. Participants played in turns, which enabled equal contributions. The game did require speaking as well as multisensory engaging by observing, listening and moving things around. It was perceived as a diverting time and allowed everybody to actively take part.

- Horizontality and agency. The game structure allowed the researcher to act as a facilitator rather than as a leader, setting the rules at the beginning of the session before letting the participants appropriate them. The playfulness fostered a positive group dynamic that increased participants’ engagement.

- Collaborative information mapping. The game built on the information horizons mapping technique, which graphically represents individual’s information seeking behaviour (Sonnenwald, Wildemuth and Harmon, 2001). However, it shifted the focus from information seeking to everyday information practices, thus including information sharing activities. Moreover it used a real city map which participants collaboratively interacted with, helping each other navigate the city.

Participants indicated functional needs, such as food, English language and IT skills, as well as leisure activities. Their main barrier to information was lack of money, preventing internet access, or affording bus tickets between the accommodation provided by authorities and the city centre, where most flags were located. Social interactions – as suggested by previous works - appeared to be their main source of information. Social networks were developed through the activities and services provided by local charities and community groups, which allowed them to meet their needs and represented most of the locations flagged. When reflecting on this finding, participants concluded that there were sufficient services to help them, since they had managed to collectively map them, but that these were difficult to find for a newcomer alone because the charities providing them lacked visibility, due to their lack of resources. To mitigate this gap, participants discussed the creation of a website where all information necessary for new asylum seekers could be centralised, although internet connection and digital literacy would limit its access.

The most interesting aspect of the information mapping board game was an unexpected one: the possibility to break its rules. In the middle of the session, participants took over the game and, rather than indicating instances when they sought or shared information in the past, they started sharing information with their co-players directly during the game. They shared tips on where to find free food, courses, leisure activities, and cheap mobile phone companies. Thus, they transformed the game into an information ground and displaced the competition to who knew the city best and could make the most of their situation. As they became aware of how they had managed to make sense of the system and make the most of it, they seemed to gain confidence. Sharing information thus appeared more important than seeking information, for it meant appropriating the city and showcasing expertise.

Conclusion and next steps

The information mapping board game provides a novel exploratory technique for the identification of refugees’ and asylum seekers’ information practices on a city scale. The game’s playfulness allows engaging people with different language and education levels, and fosters participants’ agency by providing them with tools to play with and the possibility to take over the game. Its friendly competition allows participants to work collaboratively and become aware of their acquired information literacy by sharing their knowledge with others. The contextual nature and limited volume of data collected from the game means that findings cannot be generalized and would not be sufficient to enable a satisfactory analysis as a stand-alone technique. Subsequent data collection will further address this. A cross-analysis of results emerging from different groups may provide a rich picture of information affordability and barriers to inform local community-based actions and policies.

Acknowledgements

This pilot study is part of a research project funded by the University of Northumbria. We would like to thank the participants for playing along. We are grateful to Gobinda Chowdhury and Ed Hyatt for their comments on earlier versions of this paper and inputs to this research, and to the reviewers for their helpful suggestions and observations.

About the authors

Kahina Le Louvier is a Ph.D. candidate in the department of Computer and Information Science at the iSchool of the University of Northumbria, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK. Her research focuses on the information and heritage practices of people going through the British asylum system. She can be contacted at kahina.lelouvier@northumbria.ac.uk.

Perla Innocenti is a Senior Lecturer in Information Sciences at the iSchool and NorSC Lab of the University of Northumbria, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK. Her research focuses on preserving, curating and making accessible cultural heritage. She is currently investigating articulations between technology and intangible heritage practices, together with ways in which cultural institutions might support the social inclusion of marginalised groups. She can be contacted at perla.innocenti@northumbria.ac.uk.

References

- Alam, K. & Imran, S. (2015). The digital divide and social inclusion among refugee migrants. Information Technology & People, 28(2), 344–365.

- Allen, M., Matthew, S. & Boland, M.J. (2004). Working with immigrants and refugee populations: issues and Hmong case study. Library Trends, 53(2), 301–328.

- Biggs, S. (1989). Resource-poor farmer participation in research: a synthesis of experiences from nine national agricultural research systems. The Hague: International Service for National Agricultural Research.

- Caidi, N. & Allard, D. (2005). Social inclusion of newcomers to Canada: an information problem? Library and Information Science Research, 27(3), 302– 324.

- Clarke, A.E. (2005). Situational analysis: grounded theory after the postmodern turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Díaz Andrade, A. & Doolin, B. (2016). Information and communication technology and the social inclusion of refugees. MIS Quarterly, 40(2), 405–416.

- Gifford, S. M. & Wilding, R. (2013). Digital escapes? ICTs, settlement and belonging among Karen youth in Melbourne, Australia. Journal of Refugee Studies, 26(4), 558–575.

- Glaser, B.G. & Strauss, A.L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York, NY: Aldine Publishing.

- Hicks, A. & Lloyd, A. (2018). Seeing information: visual methods as entry points to information practices. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 50(3), 229-238.

- Kennan, M.A., Lloyd, A., Qayyum, A. & Thompson, K. (2011). Settling in: the relationship between information and social inclusion. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 42(3), 191–210.

- Kindon, S., Pain, R. & Kesby, M. (Eds.). (2007). Participatory action research approaches and methods. London, New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kirkup, J. & Winnett, R. (2012, May 25). Theresa May interview: we're going to give illegal immigrants a really hostile reception. The Telegraph. Retrieved from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/immigration/9291483/Theresa-May-interview-Were-going-to-give-illegal-migrants-a-really-hostile-reception.html.

- Lloyd, A. (2014). Building information resilience: how do resettling refugees connect with health information in regional landscapes – implications for health literacy. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 45(1), 48-66.

- Lloyd, A. (2015). Stranger in a strange land; enabling information resilience in resettlement landscapes. Journal of Documentation, 71(5), 1029–1042.

- Lloyd, A. (2017). Researching fractured (information) landscapes. Journal of Documentation, 73(1), 35–47.

- Lloyd, A., Pilerot, O. & Hultgren, F. (2017). The remaking of fractured landscapes: supporting refugees in transition (SpiRiT). Information Research, 22(3), paper 764. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/21-1/paper764.html (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/6tTRmq2S2).

- Lloyd, A. & Wilkinson, J. (2016). Knowing and learning in everyday spaces (KALiEds): mapping the information landscape of refugee youth learning in everyday spaces. Journal of Information Science, 42(3), 300–312.

- Oduntan, O. & Ruthven, I. (2017). Investigating the information gaps in refugee integration. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 54(1), 308-317.

- Olden, A. (1999). Somali refugees in London: oral culture in a Western information environment. Libri, 49(4), 212–224.

- Pettigrew, K.E. (1999). Waiting for chiropody: contextual results from an ethnographic study of the information behaviour among attendees at community clinics. Information Processing and Management, 35, 801–817.

- Qayyum, M.A., Thompson, K.M., Kennan, M.A. & Lloyd, A. (2014). The provision and sharing of information between service providers and settling refugees. Information Research, 19(2), paper 616. Retrieved from http://InformationR.net/ir/19-2/paper616.html

- Quirke, L. (2012). Information practices in newcomer settlement: a study of Afghan immigrant and refugee youth in Toronto. In Proceedings of the 2012 iConference (pp. 535–537). New York, NY: ACM.

- Quirke, L. (2015). Searching for joy: the importance of leisure in newcomer settlement. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 16(2), 237–248.

- Shankar, S., O’Brien, H.L., How, E., Lu, Y., Mabi, M. & Rose, C. (2016). The role of information in the settlement experiences of refugee students. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 53(1), 1–6.

- Sonnenwald, D.H., Wildemuth, B.M. & Harmon, G.L. (2001). A research method to investigate information seeking using the concept of information horizons: an example from a study of lower socio-economic students’ information seeking behavior. Association of Library and Information Science Education (ALISE), 2, 65–86

- Varheim, A. (2014). Trust and the role of the public library in the integration of refugees: the case of a Northern Norwegian city. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 46(1), 62–69.