Searching databases without query-building aids: implications for dyslexic users

Gerd Berget

Institute of Information Technology, Faculty of Technology, Art and Design, Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, Oslo, Norway

Frode Eika Sandnes

Faculty of Technology, Westerdals Oslo School of Arts, Communication and Technology. Oslo, Norway

Introduction

Online databases are important sources for scholarly information. There is a growing reliance among students on search engines such as Google (Jamali and Asadi, 2010). General search engines often have basic search interfaces as the default option, where the user inputs all the search terms in one search field. Further, these systems often offer full text search, allowing the users to search with natural language. Search engines may also have a high tolerance for spelling errors and offer various query-building aids. Autocomplete is an example of a query-building aid where query-terms are suggested while the user is entering the query. Query-building aids may also return relevant results even if queries are misspelled.

General search engines do not fully accommodate the needs of students and scholars. Additional resources such as library catalogues and article databases are often required to locate articles on reading lists and to find relevant citations for written assignments. Domain specific search systems often contain advanced interfaces with several search fields, which require different content such as author names, titles or keywords. Moreover, these databases do often not offer full text search. Although a database may provide synonym control, there are higher demands on users to input query terms matching the vocabulary of the database. Bibliographic databases often have a low or no tolerance for spelling errors and offer no query-building aids. Such systems require well-developed writing and reading skills, which are typically impaired in dyslexic users. It is suggested that students with impairments such as dyslexia struggle with information seeking (Hepworth, 2007; "MacFarlane, Al-Wabil, Marshall, Albrair, Jones and Zaphiris, 2010; MacFarlane, Albrair, Marshall, and Buchanan, 2012; Habib et al., 2012). Dyslexics may also have difficulties in using physical libraries, and thus rely on extra library support (Mortimore and Crozier, 2006).

The number of dyslexic students entering higher education is increasing (Tops, Callens, Lammertyn, Van Hees and Brysbaert, 2012). Information literacy is often emphasised as a strategy for lifelong learning (Association of College and Research Libraries, 2000) and access to scholarly literature is important to this end. Inaccessible search systems may be an obstacle in completing a higher education qualification for dyslexic students. Consequently, there is a need for more accessible search systems, but to date little is known about the information searching behaviour of dyslexic users in order to facilitate these more accessible search systems (Hepworth, 2007; MacFarlane et al., 2012). The novel contribution of this study is to provide new empirical evidence on how dyslexia affects information search. For example, do dyslexic students take longer and formulate more queries per task than the students without dyslexia, do dyslexics submit shorter queries, make more misspellings and rely more on external resources than users without dyslexia. Such empirical knowledge is needed to develop design guidelines which better accommodate search experiences for dyslexic users.

This study involved forty students (twenty with dyslexia and twenty controls) who each solved ten predefined search tasks in the Web-based Norwegian library catalogue Bibsys Ask. The null hypothesis herein was that dyslexia would not affect overall search performance. It was expected that several search parameters would be affected by dyslexia, which typically causes spelling and reading difficulties (Snowling, 2000). It was assumed that spelling skills would affect the time taken to pursue a query, the number of queries needed to solve a task, query lengths and portion of misspellings. Further, reading skills could affect query lengths, since it was assumed that slow readers would formulate queries with a higher precision level to reduce the effort needed to browse result lists. It was also assumed that a broad range of problem-solving approaches would be applied. The following hypotheses were the basis for the study:

H1: Dyslexic users take more time formulating queries than controls.

H2: Dyslexic users formulate more queries per task than controls.

H3: Dyslexic users submit shorter queries than controls.

H4: Dyslexic users produce more misspellings than controls.

H5: Dyslexic users apply a broader range of problem solving strategies than controls.

Background

Dyslexia is a learning disorder which affects 3-10% of the general population (Snowling, 2000). Although the etiology is disputed (Jones, Branigan and Kelly, 2007; Schuchardt, Maehler and Hasselhorn, 2008), dyslexia is commonly connected to an underlying phonological deficit (Snowling, 2001). Dyslexia typically affects reading and writing activities however impairments in word retrieval, working memory, concentration and rapid naming skills are also prevailing (Snowling, 2000; Snowling, 2001; Mortimore and Crozier, 2006; Smith-Spark and Fisk, 2007). Rapid naming skills concern the ability to connect visual and oral information by assigning appropriate names to, for instance, numbers, colours or objects (Lervåg and Hulme, 2009). Difficulties related to dyslexia persist until adulthood and remain throughout life (Swanson and Hsieh, 2009).

Information searching involves a variety of cognitive skills. For instance, rapid naming skills and word retrieval are used to formulate effective search queries. Spelling skills are needed to input terms correctly (MacFarlane, Albrair, Marshall, and Buchanan, 2012). Reading skills and a good working memory are required when browsing result lists and assessing documents. Several of these skills are often impaired in dyslexic users. Consequently, dyslexia may have a negative effect on search performance, especially in systems with no query-building aids and no tolerance for spelling errors.

The field of human computer interaction has become increasingly concerned with user diversity and the importance of accessible interfaces (Henry, Abou-Zahra and Brewer, 2014). Universal design is included in several national legislations (Imrie, 2012). The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) is often referred to in this context. However, these guidelines may not meet the needs of users with various disabilities (Rømen and Svanæs, 2012) or users in cognitive language and learning areas (W3C, 2008) such as dyslexia (Freire, Petrie and Power, 2011; deSantana, Oliveira, Almeida and Baranauskas, 2012). Further, existing guidelines typically address general Website design, and not specific issues related to search systems.

More knowledge about user behaviour is needed to develop effective interface guidelines. Dyslexics have received little attention in studies on Web accessibility and search systems (de Santana, Oliveira, Almeida and Baranauskas, 2012; McCarthy & Swierenga, 2010). Furthermore, most research on dyslexia and Website design address navigation (Al-Wabil, Zaphiris and Wilson, 2007), font types, font sizes (Rello and Baeza-Yates, 2013; Rello, Pielot, Marcos and Carlini, 2013) and accessible textual content (Evett and Brown, 2005). Consequently, few documented studies exist about information retrieval and the actual use of search interfaces by dyslexic users.

General user-centred theories and models on information seeking behaviour do generally not address users with impairments. Some studies address blind library users, for instance Craven & Brophy (2003) and Sahib, Tombros and Stockman (2012), while cognitive disabilities have received less attention (MacFarlane, Al-Wabil, Marshall, Albrair, Jones and Zaphiris, 2010). Of the few studies that addressed general cognitive abilities as possible predictors of information searching Kim and Allen (2002) investigated whether cognitive abilities such as different levels of perceptual speed, spatial scanning and logical reasoning affected the information seeking behaviour of students searching the Web. Other studies discuss how cognitive style or learning style affects the retrieval process, for instance Palmquist and Kim (2000), Papaeconomou, Zijlema and Ingwersen (2008) and Al-Maskari and Sanderson (2011).

Of the few studies that addressed how dyslexia affects information searching behaviour MacFarlane et al. (2010) compared the search behaviour of 5 dyslexics and 5 controls in the test retrieval system Okapi. The results from this study were that dyslexic users on average exhibited fewer search iterations, took more time on each search and reviewed fewer documents than the controls. The authors found no misspellings and could therefore not explain how such mistakes affect query variables. A later study by MacFarlane et al. (2012) investigated the search behaviour of 8 dyslexics and 8 controls with a focus on the phonological working memory. The phonological working memory includes spoken and written material and is often impaired in users with dyslexia (Smith-Spark and Fisk, 2007). Participants in the control group classified more documents as irrelevant than the dyslexia group. Furthermore, the authors found a correlation between working memory and the ratio of documents classified as irrelevant. The conclusion was that there is a need for more knowledge on the information searching behaviour of users with dyslexia.

Berget and Sandnes (2015) observed the information searching behaviour of 20 dyslexics and 20 controls solving ten predefined search tasks in the general search engine Google with query building aids. Although the dyslexics made more misspellings, there were no significant differences in time usage or number of queries per task compared to controls. The dyslexic students fixated significantly less on the screen and the autocomplete suggestions while entering queries than the controls. Berget and Sandnes (2015) concluded that a high tolerance for spelling errors may be as useful as autocomplete functions for dyslexic users, because of the extensive focus on the keyboard during text entry. Results from this study also indicate that help functions such as displaying a red line beneath misspelled words in the search field, may be helpful to users.

Method

Participants

The study included 40 volunteering students, 20 diagnosed with dyslexia and 20 controls. The participants were recruited through advertisements by the interest association Dyslexia Norway, announcements in classrooms and on Websites. Four of the participants (three dyslexics and one control) were diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) or Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD). ADHD and ADD are typically characterized by short attention span, excessive activity and impulsivity, and comorbidity with dyslexia is well documented (Germanò, Gagliano, and Curatolo, 2010). Participants in the control group were matched against the dyslexia group according to gender, age, field of study and year of study. Prevalence of dyslexia was the only controlled variable.

The participants included 60% females and 40% males, aged 19-40 years with a mean age of 24.2 years (SD=5.2) in the dyslexia group and 23.6 (SD=3.8) in the control group. Dyslexia is typically more prevalent among men than women (Hawke, Olson, Willcut, Wadsworth and DeFries, 2009). Consequently, the portion of male participants should have been higher. However, the skewed gender distribution was caused by recruiting difficulties.

The students were enrolled onto either three-year bachelor-programmes or two-year master-programmes, with mean year of study of 2.4, for both the dyslexia group (SD=1.2) and the control group (SD=1.0) (value 1-3 used for bachelor students, 4-5 for master students). The participants represented a diversity of disciplines and study programmes, for instance nursing, engineering, social sciences and humanities. Students from library- and information science programmes were excluded because of their extensive training in information searching. None of the dyslexic students regularly relied on assistive technologies. All participants were regarded as high-functioning dyslexics since they successfully have been admitted to higher degree programmes and have demonstrated academic progress. This may be a limitation of the study, since other groups with dyslexia may have less academic training.

Formal training and prior experience with search systems may affect information searching (Kuhlthau, 1991). Eight dyslexic participants had received formal training in searching library catalogues compared to nine users in the control group. The controls had slightly more years of experience than the dyslexics, both in using general search engines (M=14.4, SD=3.2 compared to M=13.9, SD=3.3) and library catalogues (M=4.6, SD=3.9 compared to M=3.9, SD=3.1). The students with dyslexia reported a higher frequency of use of the library catalogues than the control group.

All participants were screened for dyslexia using a word chain test (Høien and Tønnesen, 2008). The dyslexic students had previously been diagnosed by psychological or pedagogical professionals. However, the screening test eliminated the need for consulting sensitive medical records to confirm the dyslexia diagnosis and ensured that no controls were dyslexic. The word chain test is a standardised test in Norway which is applied in previous research, for instance Solheim and Uppstad (2011) and Dahle and Knivsberg (2014). A low score is considered indicative of dyslexia and diagnostic tests are recommended for adult scores below 43 (Høien and Tønnesen, 2008). The dyslexic students scored significantly lower (M=39.3, SD=10.3) than the controls (M=60.2, SD=10.0), t(38)=6.52, p<.001, d=2.12.

Visual acuity was measured, since reduced vision can be a source of error. Landolt C charts were used at 4 m for distance and 40 cm for near, in accordance with the European standard (ISO, 2009). All participants had at least acuity of 0.6 on each eye separately and 0.8 with both eyes open for both tests, which is considered within the limits of normal visual acuity (Zhang, Bobier, Thompson and Hess, 2011).

Procedure

The participants were instructed to solve ten predefined search tasks using the library catalogue. Instructions and search tasks were presented orally using pre-recorded speech synthesis files. Oral instructions may prevent misinterpretations of tasks, since dyslexia may affect reading speed and reading comprehension (Ransby and Swanson, 2003). Moreover, oral instructions prevented the participants from seeing the spelling of terms. The experimental design choice of introducing oral instructions places more cognitive load on the participants since they have to remember the tasks. This could be a challenge since dyslexia is also often associated with reduced working memory. However, the task of reading the instructions was considered more cognitively demanding than memorising the short oral instructions. The assumed discrepancy between reading and listening abilities among individuals with reading disabilities is also supported by the literature (Badian, 1999).

An image representing the question was displayed while instructions were given (Figure 1). The task number allowed the participants to track the progress of the session.

At the start of the session the participants were asked about prior experiences with online library catalogues including Bibsys Ask. All ten tasks were completed in one session, and there was no dialogue between the participants and the experimenter besides responses to questions initiated by the participants. The students were allowed to use external online resources as supplementary aids if needed e.g. checking the spelling of a word. They were asked to comment on their search behaviour during debriefing where unusual behaviour had been observed.

Ethics

The study was ethically screened and approved by the Norwegian Social Science Data Services (project number 29348) and all data was anonymised. Moreover, all participants signed consent forms. None of the students were related to the researchers.

Apparatus

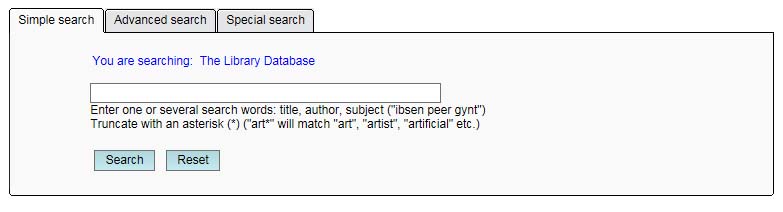

The experiments were run in the visual stimulus presentation software SMI Experiment Center version 3.2.11 using the background screen recorder. The stimulus was displayed on a 21’ Dell LED flat screen with the resolution set to 1680 x 1050 pixels. Windows Internet Explorer version 9 was used for the search tasks, with all functions related to prior use such as browsing history and cookies disabled. All searches were conducted in the basic search mode in Bibsys Ask (Figure 2). Data were analysed using SMI BeGaze version 3.2 and the statistical analysis software IBM SPSS Statistics 22.

Materials

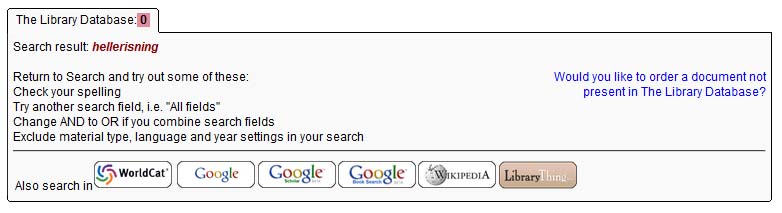

Bibsys Ask is a bibliographic library database used by all the higher education libraries in Norway, in addition to several research libraries and institutions. This database has no tolerance for spelling errors and provides no query-building aids; the system merely instructs the user to check the spelling or modify the query if no results are returned (Figure 3).

The participants were given ten predefined search tasks in Norwegian (see Table 1). Such tasks were used to allow for a direct comparison of search strategies and query formulations between the two groups. Imposed queries may be less motivating to solve than self-generated information needs (Gross, 1995). It was assumed that the participants were motivated to solve the tasks since they had volunteered for the study. Experimental task orders are often randomized to counterbalance learning effects. In this study, however, the search tasks were presented in a fixed order. The students had prior experience with the search system and it was assumed that the learning-effects would be minimal. The key design consideration was not to make the participants feel uncomfortable or lose courage during the session because of the varying difficulty levels of the tasks and poor self-esteem issues among many dyslexic students (Caroll and Iles, 2006). Consequently, the tasks were presented in increasing order of difficulty.

| Task | Task (originally given in Norwegian) | Expected query terms | Translated query terms |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Find a document about Vigeland Sculpture Park? | Vigelandsparken | Vigeland Sculpture Park |

| 2 | In which year was the book “Rock carvings in Hedmark and Oppland” published? | helleristninger Hedmark Oppland |

rock carvings Hedmark Oppland |

| 3 | Find a book written by Sigrid Undset about Kristin? | Sigrid Undset Kristin |

Sigrid Undset Kristin |

| 4 | Find a document on stagecraft and lighting? | sceneteknikk lyssetting |

stagecraft lightning |

| 5 | Find a document on cyberbullying? | digital mobbing |

cyberbullying |

| 6 | Who is the author of the books about Albert and Skybert? | Albert Skybert |

Albert Skybert |

| 7 | Find a document about Norwegian recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize? | norske vinnere Nobels fredspris |

Norwegian recipients Nobel Peace Prize |

| 8 | Find a book on Knut Hamsun and Nazism? | Knut Hamsun Nazisme |

Knut Hamsun Nazism |

| 9 | Find a document about women in Algeria? | kvinner Algerie |

women Algeria |

| 10 | Find a play written by William Shakespeare? | William Shakespeare |

William Shakespeare |

The search tasks were based on gender-neutral and common topics. They were not related to any particular study programmes, preventing prior knowledge to affect search behaviour. One correct answer was deemed sufficient to solve each task. The tasks were designed to provoke spelling errors allowing for a study of how search behaviour is affected by reduced spelling skills. The tasks included words which dyslexic users frequently misspell, such as compound words: fredspris, double consonants: Oppland, consonant clusters: Undset, silent consonants: Sigrid (d is not pronounced), silent vowels: Algerie (e is not pronounced) and words with irregular orthography, where the spelling and pronunciation differs: Shakespeare (Helland and Kaasa, 2005; Lyster, 2007; Høien and Lundberg, 2012). Although the search tasks represent a moderate complexity level, it was assumed that the tasks would be perceived most difficult for dyslexic users.

Results

The query characteristics are summarised in Table 2. Dyslexic students took significantly longer to complete each task (M=47.8 s, SD=14.6 s) compared to controls (M=29.0 s, SD=8.2), t(38)=5.02, p<.001, d=1.63. Although the dyslexia group took longer on each query (M=19.8 s, SD= 5.1) than the control group (M=17.0 s, SD=3.6), the difference was not significant, t(38)=1.95, p>.058, d=0.63.

| Dyslexia group | Control group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p t-test) | |

| Search time (s) per task | 47.8 | 14.6 | 29.0 | 8.2 | <.001 |

| Search time (s) per query | 19.8 | 5.1 | 17.0 | 3.6 | >.058 |

| Number of queries per task, overall | 2.5 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.3 | <.001 |

| Number of queries per task, Bibsys | 2.1 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.3 | <.001 |

| Number of queries per task, external | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | <.001 |

| Portion of misspelled queries, Bibsys | 44% | 10% | 26% | 14% | <.001 |

Dyslexic users formulated significantly more queries per task (M=2.5, SD=0.6) than the controls (M=1.7, SD=0.3), t(38)=5.42, p<.001, d=1.76. A higher submission of queries was found both in the library catalogue and external Websites. In Bibsys Ask, users with dyslexia submitted significantly more queries per task (M=2.1, SD=0.5) than the controls (M=1. 6, SD=0.3), t(38)=4.52, p <.001, d=1.47. Furthermore, the dyslexic students used external Websites significantly more per task (M=0.4, SD=0.3) than the control group (M=0.1, SD=0.1), t(38)=4.31. p<.001, d=1.40. All external searches were conducted in Google, except one online dictionary query. No users in the control group relied on external Websites for task five, six and seven.

Dyslexic students misspelled more queries (M=0.44, SD=0.10) than the controls (M=0.26, SD=0.14), t(38)=4.59, p <.001, d=1.49. The number of spelling errors was higher for all search tasks. None of the controls made spelling errors on task five and six.

Concerning query lengths (see Table 3), dyslexic users included significantly fewer search terms per query (M=2.05, SD=0.23) than the controls (M=2.25, SD=0.18), t(38)=2.92, p<.007, d=0.95. However, when the first query was analysed separately from the remaining queries, both groups submitted similar query lengths, t(38)=1.09, p>.281, d=0.35. There were no significant differences in lengths in the last query for each task, t(38)=1.87, p>.069, d=0.47. Consequently, the shorter dyslexic query lengths appeared mainly in the intermediate queries.

| Dyslexia group | Control group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p t-test) | |

| Submitted terms per query, overall | 2.05 | 0.23 | 2.25 | 0.18 | <.007 |

| Submitted terms per first query | 2.07 | 0.28 | 2.16 | 0.27 | >.281 |

| Submitted terms per last query | 2.18 | 0.23 | 2.30 | 0.21 | >.069 |

| Minimum number of terms per query | 1.75 | 0.33 | 2.01 | 0.20 | <.006 |

| Maximum number of terms per query | 2.35 | 0.16 | 2.33 | 0.22 | >.743 |

The minimum number of terms per query was significantly lower among dyslexic users (M=1.75 terms, SD=0.33) than the controls (M=2.01 terms, SD=0.20), t(38)=3.02, p<.006, d=0.98. There were no significant differences in maximum query lengths, t(38)=0.33, p>.743, d=0.10.

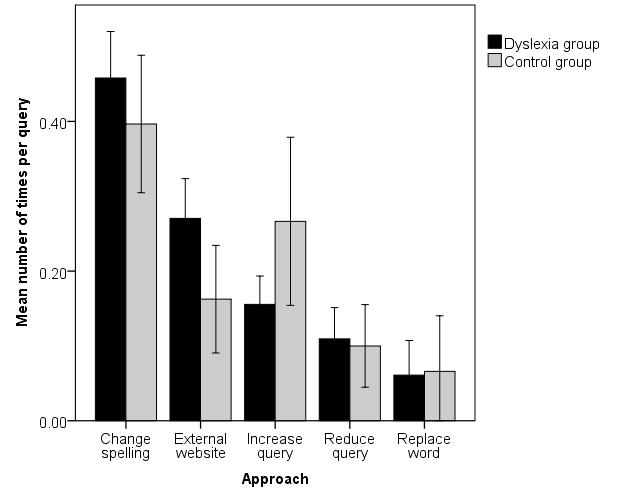

The participants applied different approaches when a query failed to return useful results, for instance using external Websites or query modifications such as altering query lengths, changing the spelling of words or replacing words (see Table 4 and Figure 4).

| Dyslexia group | Control group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p t-test) | |

| Portion of queries with changed spelling | 46% | 13% | 40% | 20% | >.252 |

| Portion of queries where external web sites are applied | 27% | 11% | 16% | 15% | <.017 |

| Portion of queries with increased query lengths | 16% | 8% | 27% | 24% | >.057 |

| Portion of queries with decreased query lengths | 11% | 9% | 10% | 12% | >.774 |

| Portion of queries with replacement of words | 6% | 9% | 7% | 16% | >.905 |

The most frequent approach involved changing the spelling of terms. Dyslexic users changed the spelling in more queries (M=0.46, SD=0.13) than the controls (M=0.40, SD=0.20). However, there were no significant differences, t(38)=1.16, p>.252, d=0.38. Consulting external Websites to identify the correct spelling of terms was the only approach with significant differences. External Websites were used significantly more by dyslexics (M=0.27, SD=0.11) than controls (M=0.16, SD=0.15), t(38)=2.53, p<.017, d=0.82. There were no significant differences in the remaining approaches such as modifying query lengths or replacing terms (see Table 4).

Discussion

Dyslexics often exhibit slow or inaccurate reading and writing (Caroll and Iles, 2006). It was therefore expected that the dyslexic users would take more time on each task than controls. This assumption was confirmed and is in accordance with the findings by MacFarlane et al. (2010). The increased time use could be explained by a higher number of queries and the use of external Websites. It is common that users with dyslexia have difficulties concentrating on a task for a long time (Mortimore and Crozier, 2006). A fatigue-related effect could therefore have caused increased search times. However, the time use did not increase during the experiment. Consequently, a more accessible interface may reduce search times for all tasks.

Users with dyslexia often have reduced rapid naming skills (Smith-Spark and Fisk, 2007), smaller vocabularies, are more limited in their choice of words (Connelly, Campbell, MacLean and Barnes, 2006) and display slower writing speeds than is usual for their age (Hatcher, Snowling and Griffiths, 2002). It was therefore expected that dyslexic users would take longer time per query compared to controls (H1), an assumption which was not confirmed. This result was unexpected. However, some of the search terms, such as author names, were included in the oral instructions, thus reducing the need for good rapid naming skills to quickly identify search terms. Moreover, dyslexic users formulated more short queries compared to the controls. Consequently, dyslexic users may have used more time per query if the query lengths had been similar throughout the experiment. These results imply that help functions which reduce the demands on query content may be helpful.

It was hypothesised that dyslexic users would formulate more queries per task than controls, an assumption which was confirmed. The observations indicate that the higher number of queries among the dyslexics was mainly caused by insufficient or too extensive result lists and misspellings, which led to query modifications and use of external Websites. These findings indicate that dyslexia has a negative effect on search performance in databases with a low tolerance for misspellings and no query-building aids.

Dyslexic users were expected to submit shorter queries than controls (H3). It was assumed that slower writing speed and a high risk of spelling errors would result in shorter queries, thus reducing search times and eliminating misspellings. Dyslexic students did submit significantly shorter queries than the controls. This difference was mainly found in the intermediate queries. There were no significant differences in query lengths when the first or last queries were analysed separately. Consequently, the participants started and ended the search sessions at approximately the same precision levels, which implies that the result lists contained approximately the same number of documents on a similar relevance level for both groups.

Query lengths affect the size and content of result lists. Precision and recall refers to a search engine’s ability to retrieve relevant documents. There is a trade-off between these two measurements. Short and general queries result in long imprecise result lists, while longer and more specific queries lead to higher precision. Precision could potentially be an aim for slow readers. Precise queries may facilitate the browsing process by reducing the size of result lists and increasing the relevance of the first documents in the list. The costs of longer queries include a higher risk of misspellings, which may explain the shorter queries in the dyslexia group. Several dyslexic participants used the built-in search-function in the browser rather than scan the result lists. This behaviour suggests an attempt to reduce work load and solve the issues regarding the contradictory relationship between precision and recall. Moreover, these findings imply that there may be a need for alterations in the presentation of result lists to better accommodate users with dyslexia.

There was a significant difference between the groups regarding minimum query lengths, but not maximum lengths. Dyslexic students submitted shorter intermediate queries, possibly to isolate the misspelling, for instance:

Q1-1: «knut hamsun nasismen», Q1-2: «knut hamsun», Q1-3: «knut hamsun nazismen».

The user removed one word in Q1-2, to verify the spelling of the author name, before the subject term was reintroduced with a different spelling. Query Q2 is an example of a similiar approach, but here the user searched with one term at a time before combining them in the last query:

Q2-1: «Sigrid Unseth», Q2-2: «Unset», Q2-3: «Kristin», Q2-4: «Kristin Unset».

Query Q1 and Q2 indicate that a lack of query-building aids or a low tolerance for spelling errors may lead to more queries to solve a task. It would have been useful if the system provided the user with more substantial information when errors occurred, for instance by indicating which terms were not matched in the database: «no results in the database for the term Unseth» as a response to Q2-1. This function would have counteracted the need for Q2-2 and Q2-3, and thus cut the number of queries by a half.

It was assumed that the dyslexic students would exhibit more spelling errors than the controls (H4). This hypothesis was supported. The number of misspellings increased according to number of search terms, which was also as expected, since the use of more terms is likely to increase the total probability of spelling errors.

The number of errors was mainly related to query lengths and the inclusion of unfamiliar or difficult words, such as helleristninger and Algerie. Previous studies have found that adults with dyslexia may memorise the spelling of familiar words, but have more difficulties with orthographic patterns which results in more errors in unfamiliar words (Kemp, Parrila and Kirby, 2009). The results from the Bibsys searches are in accordance with these findings. Moreover, these findings also support the position that autocomplete functions could be beneficial when task complexity increases. This is in accordance with the students’ comments during the de-briefing interview about the potential problematic features or shortcomings in search systems such as Bibsys Ask. All except one of the students with dyslexia mentioned the lack of spelling aids as the most prominent problem.

Although Bibsys Ask did not offer any query-building aids, the system included an authority file. Such files contain the authorised form of, for instance, author names as well as the addition of different spellings of terms. In these cases, users may retrieve results although a term is not spelled correctly if they have used a spelling which is in accordance with the variations in the file. It was anticipated that there would be many spelling errors in the William Shakespeare task. This task included terms with several challenging linguistic components, such as irregular orthography, double consonants and silent vowels. These complex linguistic components are typically difficult by dyslexic users. The last name of the author may also be regarded as an unfamiliar word. However, the library catalogue actually returned results when the query was formulated without the ‘e’ at the end of Shakespeare, because of the authority file. The participants also received results when adding a ‘d’ at the end of Hamsun. If such a mapping had not been included, the number of registered misspellings and query modifications would presumably have been even higher. Further, the use of external Websites was higher for the Shakespeare task, thus reducing the number of misspelled queries.

Several approaches for resolving misspellings were observed. Nevertheless, many errors could have been averted through autocomplete functions or spelling suggestions. However, in many searches a higher tolerance for spelling errors would have been adequate to accommodate dyslexic users. This was particularly evident in the number of Google searches where relevant results were retrieved despite misspelled queries. These results indicate that a high tolerance for spelling errors reduce the negative effect of dyslexia on search performance. Users with dyslexia often make different spelling errors than their peers (Li, Sbatella and Tedesco, 2013). Consequently, spellcheckers which accommodate the misspellings of users with dyslexia should be implemented. Such technology is already available in proprietary software. Participants without dyslexia also made spelling errors during the search sessions which shows that query-building aids would be useful for a wide cohort of users. This finding supports the work of de Santana et al. (2012).

Many dyslexics in the study claimed that they often guessed the spelling of words rather than spending time compiling the correct query. In other cases Google was used as a dictionary. Schoot, Licht, Horsley and Sergeant (2000) found that guessing while reading is not uncommon for dyslexics. However, results from this Bibsys Ask study may indicate that such guessing behaviour may also be applied during writing.

Users with dyslexia often develop coping strategies to compensate for their impairment (Borkowski, Estrada, Milstead and Hale, 1989). Consequently, it was hypothesised that dyslexic users would apply a broader range of problem solving strategies than controls (H5). However, using external Websites was the only approach that was significantly undertaken by the dyslexic users.

Google was the only external Website used by participants in the study, except for one direct search in an online dictionary. This was not surprising, since Google is a widely used search engine (Westerwick, 2013), and it has a high tolerance for spelling errors and includes autocomplete functions. The high tolerance level for misspelled queries was evident in several searches in this study. For instance, a dyslexic student received relevant results on a query despite three misspellings: «helerystninger i hedemark og oppland» (correct query «helleristninger i hedmark og oppland»).

Using external resources may be an approach based on prior experiences. Such behaviour may also be an example of least possible effort (Bates, 2002) where students try to avoid the system most difficult to use, since Google demands less effort from the users. A majority of the students found the library catalogues difficult to use compared to general search engines. Consequently, they preferred formulating the query in Google to avoid using the library catalogue.

Several dyslexics usually searched Google first to find the proper spelling before pasting the query into the library catalogue search interface. Such a strategy reduced the effort and mental load required in Bibsys Ask to compile the proper query syntax. This approach was apparent in searches with difficult spellings, where students in both groups searched Google directly on the first query. Several students mentioned that such behaviour was a result of past experiences with faulty queries in Bibsys Ask. If the students had not applied this strategy, the number of queries and misspellings could have been even more prevailing. Several students with dyslexia often used Google instead of actual online dictionaries for spell checking of Norwegian words in addition to Google translate for English terms. This may indicate that users regard Google as more accessible compared to online reference works.

Some participants revealed that they normally used Google more extensively than during this particular study. In the experimental setting they wanted to try to solve the tasks in Bibsys Ask as instructed. Consequently, the use of external resources may be even more common in the participants’ usual practices.

Queries submitted to Google were often longer and less formal than those submitted to Bibsys Ask. For instance, one student submitted the query «nobelsfredspris» (correct term Nobels fredspris,) in Bibsys Ask, which returned zero results. The student then submitted the following query to Google: «Norske vinnere av nob», whereas Google’s autocomplete suggested a correct query. This query was copied and pasted into Bibsys Ask. The increased query lengths in Google may be a response to a high tolerance for spelling errors or that the autocomplete function suggests longer queries. In this study, participants uncertain about the spelling of terms typically inputted a few letters in Google’s search interface and then selected or looked at the correct spelling in the autocomplete list. For instance, one user inputted «nob» on the task on Norwegian Nobel Peace Prize recipients and «knut» on the Knut Hamsun and Nazism task. These findings suggest that autocomplete may be helpful. Moreover, Google offers full text searching. Consequently, it may be more useful to submit longer informal queries than in bibliographic databases such as Bibsys Ask, which may explain also explain increased query lengths.

A total of 19 dyslexic users and 13 controls searched Google after submitting an erroneous query in Bibsys Ask, rather than modifying the query in the library catalogue. However, several participants actually resolved the misspellings themselves through the altered query submitted to Google. Consequently, the students could have solved the task directly in Bibsys Ask without relying on Google. This may imply that users do not want to spend much time troubleshooting, but rather go directly to a more familiar and tolerant search system when errors occur. Such behaviour may also be caused by a lack of confidence, which is often seen in users with dyslexia (Jordan, McGladdery and Dyer, 2014).

In one case where Google returned results despite misspellings the user was not given feedback of the spelling error. When a relevant result list was presented despite the misspelling, the student did not realise the spelling error and continued searching Bibsys Ask with the erroneous query. Consequently, this user took more than three minutes solving the task. This behaviour indicates that users may rely on feedback of mistakes. This is also in accordance with general principles of human computer interaction design (Norman, 2013).

Users seem to rely quite uncritically on the suggestions provided by Google. In two searches for Norwegian recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize, the dyslexic users got the suggestion «norske nobel vinnere» by Google, which was pasted into Bibsys Ask. This was not an incorrect suggestion, since these two words do have meaning separately in Norweian. However, in this particular task, the last two words had to be one compound word: «norske nobelvinnere» to solve the task. The users did not notice that the query was incorrect and submitted three additional queries each to Bibsys Ask. This finding indicates that Google´s query-building tool sometimes is suboptimal.

Changing spelling was the most frequent problem solving approach within both groups. The dyslexic users seemed especially aware of common mistakes such as double consonants and compound words, and rephrased queries accordingly, for instance:

Q3-1: «scene teknikk», Q3-2: «sceneteknikk».

Another user tried different ways of spelling, based on double consonants, in addition to the nd- and dt-sound which may also be problematic for users with dyslexia:

Q4-1: «Sigrid Undsett», Q4-2: «Sigrid Unsett», Q4-3: «Sigrid Unnsett», Q4-4: «Sigrid Unnsedt» (...) (correct spelling Sigrid Undset)

These queries indicate that the search performance would have been approved if the system had suggested the correct spelling.

Changing the spelling of a term is a self-evident strategy for modifying a misspelled query. However, other approaches included replacing or excluding difficult words. Such strategies were especially noticeable in the task on the author of the books about Albert and Skybert (in Norwegian the Sk is pronounced sh, making it potentially difficult to spell). On this task, 25% of the dyslexic users searched with «Albert Åberg». This query was based on prior knowledge of this children’s book character’s last name, which was not included in the instructions, thereby avoiding a difficult term. This strategy was also found in 25% of the searches by the controls. The results from this study indicate that word replacement might be a common strategy for all users, and is not a particular characteristic of dyslexic users.

Replacements were also applied in intermediate queries. For instance, one student with dyslexia used this approach when looking for «Helleristninger i Hedmark og Oppland» and Hedmark was regarded difficult to spell (Q5-4):

Q5-1: «helleristinger», Q5-2: «helleristinger hedmark», Q5-3: «helleristinger hedemark», Q5-4: «helleristinger i oppland»

The replacement approach may not always be successful in bibliographic databases such as Bibsys Ask. In a full text database it is plausible that synonyms are applied to vary the writing style. However, in a bibliographic database the query should match the terms included in the metadata, such as names, titles or subject headings. However, tools such as synonym control or thesauri may provide results although the query contains non-preferred terms. In these cases the replacement approach could be productive. Consequently, search systems should support such functions to accommodate users who exhibit this type of query modification.

Finally, several students with dyslexia mentioned asking a librarian as a commonly used problem solving approach. One dyslexic student had given up searching the library catalogue altogether, and always got help from librarians because locating literature by using the database was too time-consuming. This is in accordance with Mortimore and Crozier’s (2006) findings that a majority of the students with dyslexia in higher education used or wanted extra library support. It is also an example of least possible effort (Bates, 2002). However, such situations should be avoided by providing all users with accessible interfaces and excessive training.

Conclusion

The results from this study indicate that users with dyslexia struggle when searching databases with a low tolerance for errors and no query-building aids. Dyslexic users took more time, formulated more queries, submitted shorter queries and made more misspellings than controls. Further, they relied more on external Websites to solve tasks. However, if functions that reduce the demands for correct spelling are implemented, the interface may become more accessible and thus reduce the negative effect of dyslexia. For instance, search systems could contain the following functions:

- feedback on which part of a query where there is no match

- suggest terms if misspellings occur

- allow users to replace difficult terms (synonym control)

- suggest queries while the user is entering queries (autocomplete)

- tolerance for spelling errors, including errors typically made by dyslexic users

Moreover, the result lists should be more accessible, for instance by including more visual information such as images or icons. Further research is needed to identify more effective result list designs and investigate whether textual or visual content is easiest to browse through for dyslexic users.

Users without reading or writing disorders also make spelling errors, which was evident in this study. Misspellings can occur for variety of reasons, for instance if users are inputting text too fast, using an unfamiliar keyboard, inputting unknown words or if the user is tired or unfocused. Consequently, improving an interface to accommodate dyslexic users will enhance the search experience for all users. This finding is consistent with other studies (McCarthy and Swierenga, 2010; Boldyreff, Burd, Donkin and Marshall, 2001).

No significant differences in problem solving approaches were uncovered, except for a more frequent use of external resources among dyslexic users. The widespread use of a system with query-building aids and a high tolerance for errors may indicate that such systems are perceived more accessible. However, this can also be attributable to more experience with Google than the library catalogue.

Query lengths indicated that there were no significant differences in precision levels, which implies that users with and without dyslexia may have similar basic search skills. The differences in search behaviour may be merely caused by impaired reading and writing skills. However, since many search terms were included in the assignments, the study did not reveal if dyslexia affected the selection of proper search terms.

Results from this study seem to strengthen the assumption that search interfaces with a low tolerance for spelling errors and no query-building aids are not accessible for users with dyslexia. More specific guidelines are needed to reduce the need for extra support and strengthen the independence, thus reducing the need for extra library support.

Acknowledgements

This project has been financially supported by the Norwegian ExtraFoundation for Health and Rehabilitation through EXTRA funds grant 2011/12/0258. The authors are grateful to the volunteering students and Dyslexia Norway for help recruiting participants.

About the authors

Gerd Berget is a PhD student at Institute of Technology at Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences. Her research includes universal design, information searching behavior, dyslexia and eye tracking studies. She can be contacted at gerd.berget@hioa.no.

Frode Eika Sandnes is a professor at the Institute of Technology at Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences and at the Faculty of Technology, Westerdals Oslo School of Arts, Communication and Technology. Oslo, Norway. His research interests include human computer interaction, universal design and pattern matching. He can be contacted at frode-eika.sandnes@hioa.no.