Learning from student experiences for online assessment tasks

M. Asim Qayyum and David Smith

Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, Australia

Introduction

Searching and finding information is a human trait that has been transformed with the advent of Web based technologies. The use of common search engines such as Yahoo, Google and Bing has increased exponentially the amount of data that individuals can have access to (Jansen, Liu, Weaver, Campbell and Gregg, 2011) and the sharing of information through platforms such as Wikipedia, as well as social media networks, effectively creates knowledge sharing communities. However, with so much data available it raises questions on how to effectively search for information and then, just as importantly, how much of that information is effectively absorbed and retained by this new generation of students entering the higher education system today. To address these questions, this study was conducted to examine the availability and selection of information tools and impact of their usage on the design of online assessments in the academic environments of students. A mixed methods approach was adopted to explore the information and learning behaviour of students when they engaged with online course-related reading material.

The emphasis of this study is on investigating the tool usage patterns and information behaviour of students in the context of their learning needs in an online academic environment. The specific research goal was then to investigate distinct patterns of information behaviour in online assessment tasks by investigating the use and management of information tools, as well as the subsequent manipulation of information by students. The online assessment tasks used in this study were of the Web based task types, which are normally embedded within distance learning education modules to quickly test student learning on a specific topic.

For the purpose of this project, the term information tools has been defined as any computer based application that students may use to find information on the Web, for example search engines, video dissemination services like YouTube, library catalogues, social media (including blogs, wikis), and even organizational Web portals that package relevant information according to the needs of their viewers. Emphasis is on computer applications that provide users with several varied sources of linked information to choose from. Findings from this study are expected to enhance our understanding of how the structure and scaffolding of an online assessment can be improved by observing selection and use of information tools by students, and the related information-seeking and browsing activities that happen when such tools are used.

This study is significant because a better understanding of online behaviour of new university students will help educators across a range of disciplines plan and create improved online learning assessments and activities. Creating online learning exercises for the appropriate academic stage of degree study is important as it provides a scaffold for students whose tertiary study settings and requirements vary. In such cases, learning from the learner's online behaviour using video monitoring, interviews, and eye tracking devices is a great way to optimise and design material suited to a student's needs.

The value and need of the study relates to preferences for online information formats and content by students, and thus to the quality and effectiveness of user/information interactions. Given the trends identified in the literature, online information tools, learning materials and other services are here to stay, making this investigation important. Prior research in the fields of education and information science come together to make a contribution in this regard as indicated in the design of this study.

Review of the literature

Customising technology use to enhance learner experience provides users with an affordance (McLoughlin and Lee, 2007) to capitalise and benefit from technology. Current applications in cloud computing, augmented reality and 3-D printing ensure that multimodal information is available at any time, experiments can be conducted through simulations and designs can be produced quickly and cheaply; these are just some examples where technology is meeting learning needs by design. However, the well practiced and familiar ability to use Internet search engines and social media platforms are not at the forefront of technology development when it comes to learning needs of students. University students often struggle with various aspects of information literacy even though their access to technology has improved and they appear to be very comfortable in its usage (Rowlands et al., 2008). Thus finding the right information, using the right tool, from the right (credible) source is still problematic for most students. Moreover, radical use of technologies in a sophisticated manner to make use of the increasing set of information platforms is still considered a myth for even the digitally knowledgeable students (Margaryan, Littlejohn and Vojt, 2011) because students will try to conform to a conventional pedagogy with minimal use of only the technologies that deliver content, such as, for example, Google or Wikipedia. One reason stated is that the teaching staff, which does experiment with newer technologies, usually reverts back to established tools and methods and is reluctant in the use of emergent social technologies. The students then simply follow the trends set by their instructors.

The need for information is pivotal and foundational to the learning experience and the students must be able to develop effective search strategies to find, refine, and absorb that information. These trends indicate an opportunity to learn from and customise the online practices of students through improvements in learning materials to increase the efficiency of information retrieval. Garrison, Anderson and Archer (2000) suggest that there is a lack of guidance given to students when lecturers design online information seeking activities, however, if attention was given to refining technology's capacity to generate information then it is likely that students would be better able to construct and convey their understanding (Oliver, Harper, Wills, Agostinho and Hedberg, 2007).

There are a few studies that explore the use of Internet resources technologies by students in general (for example (Kennedy, Judd, Churchward, Gray and Krause, 2008; Li, 2012; Rowlands et al., 2008; Thompson, 2013) but none that specifically focus on the informative components of these technologies for student learning. Moreover, the use of these technologies and tools in online assessment tasks has not been explored previously. For example, Head (2007) looked only at the use of resources available to thirteen undergraduate students enrolled in humanities and social sciences classes for a four- to six-page research paper, and concluded that most students used library or instructor provided resources rather than relying on Internet based tools like Google and Wikipedia. Li (2012) reports from a study, including eleven undergraduate students over three semesters in Hong Kong, that a search engine is often used as a starting point before switching to university provided resources.

Some of the technological tools identified from the literature that are commonly used by students in their learning are: content made available by instructors (in Learning Management Systems); Google, Google Scholar and Google Books; mobile phones and messaging (including text messaging); Wikipedia; and other Websites (Head, 2007; Kennedy et al., 2008; Li, 2012; Margaryan et al., 2011). Interestingly, Kennedy's study indicates most students still wanted some training in technology use for university learning despite the fact that they were reportedly comfortable in its usage. This fact highlights the importance of an investigation into the use of these tools for informational and learning design purposes, which has not been explored much in the literature; a gap this current research project aims to fill.

The reading habits of students are experiencing a shift in general, and the on-screen reading trends indicate a shift towards nonlinear reading and skimming content rather than following the content very closely (Liu, 2005). The debate on which format (online versus paper) is better will undoubtedly continue for a while, but others (Coiro, 2011; Konnikova, 2014) argue that online distractions affect a reader's focus more than the environment itself. Online readers tend to do more online browsing and spend less time on sustained in-depth reading (Liu, 2005) and hence take longer time to comprehend content given the perceived time pressures. Take away the Internet, hence the distractions, and readers are likely to read on screen as well as they do on paper, especially if they also take notes along the way (Subrahmanyam et al., 2013). The differences may be pronounced however if longer texts are to be read online as, due to the varied distractions, readers can spend longer times in front of the computer screens while reading articles. And the importance of time devotion to reading has been pointed out by Cull (2011):

The power of reading, whether of print or online text, continues to lie in this power of time - time to digest words, time to read between the lines, time to reflect on ideas, and time to think beyond one's self, one's place, and one's time in the pursuit of knowledge.Cull recommends that it then becomes the responsibility of university educators to motivate the students to set aside the time required for in-depth reading. These skills take time to develop and can continue to develop in students even after graduation but the main central theme is that online reading habits of students need to be refined earlier on in higher education institutes. For example, Head (2007) reports that most students in her study felt a little challenged by research assessments and 11 of her 13 participants felt that the instructors should have given them more information. Li (2012) reports similar findings and recommends that lecturers need to address these shortcomings during class times. Also in this context, Coiro (2011) presents a plan to develop the mindset readers need to adopt when they approach online texts to improve their navigating and negotiating skills, develop pathways, and learn to respond to or reflect on the content.

A challenge in learning from Internet based material is the sheer amount of information available online that can potentially hinder deep reading, even if the reader is not distracted by miscellaneous elements that are ever present in cyberspace. In a comprehensive study of the Web browser logs of 25 participants, Weinreich, Obendorf, Herder and Mayer (2008), analysed nearly 60,000 first page visits to conclude that 17% of new pages were visited for less than 4 seconds, while nearly 50% of the first page visits lasted less than 12 seconds. Longer Webpage stay duration measurements in that study carried an error factor as the count included opened sites that people forgot to close as they moved on to other tasks. Or in other words, the users generally glimpse or scan over the information to pick up keywords rather than doing any actual reading. Most user stops on Google search results were even shorter (ranging from 2-12 seconds), and understandably there were no lengthier stays. Thompson (2013) reports similar searching trends from a survey of 388 first year students, where it is suggested that students use the search engines to 'get in, get the answer, get out'. Given these short stays, it is essential that readers be trained in speed reading techniques, or as Thompson recommends, students be given explicit instruction in forming search terms and evaluating the discovered information.

A study (Rowlands et al., 2008) exploring students online interactions with e-books and e-journals made available through an academic library shows little improvement in user retention and reading times. The researchers in this case looked at previous literature and combined it with log analysis of university students to indicate that users typically spend only 4 minutes on e-book sites and 8 minutes on e-journal sites. Indeed, people generally view only a page or two from an academic site before exiting, and then they power browse horizontally through several articles hoping for quick wins and in the process, avoid reading in the traditional sense.

With no distractions and working with a limited set of focused documents, Internet learners seem to perform equally well on screen and on paper, in learning and comprehension, as has been shown by some research works e.g. (Eden and Eshet-Alkalai, 2013; Moyer, 2011). However, paper formats still come out a winner when it comes to lengthier and denser contents (Stoop, Kreutzer and Kircz, 2013). In his overview of digital reading, Liu (2012) concludes that online reading behaviour of young adults is evolving as they develop new strategies to deal with new technologies. However, active reading (including annotations and highlights) usually accompanies in-depth reading and it is unlikely that the preference for paper as a medium for active in-depth reading will disappear soon. Though online reading trends continue to grow and students will continue to use the online media for active reading as much as the technology allows. It is up to the educators to guide them in its usage.

Watching videos on the Internet is another interesting aspect that needs further exploration in conventional education and learning. Time requirements and the sequential nature of content access are some of the visible bottlenecks that need to be overcome, and one suggested manner is make available the text, or at least a summary of the video, to help the readers decide if they wish to spend the time (Schade, 2014). That way, the users have more control over what video, and/or part of it, they wish to access. Otherwise, as Margaryan et al. (2011) discovered, more than 50% of year three university students never use videos during formal learning, while a little over 10% of students use videos regularly in their learning work. Hardly any of them created videos for learning related sharing purposes as virtually all of them were consumers. The latter aspect is very important as videos can be used by educators to create learning communities where all students come together to contribute content (Duffy, 2007). Instructors can benefit from learning some strategies for using videos in learning, as outlined by Duffy, and students should be guided in the use of videos in assessment tasks so that they are encouraged in its uptake.

This paper depicts one aspect of information technology in education by describing an exploratory study that examined how university students use information tools in conjunction with reading and information seeking activities to undertake a learning task. The study is significant as the results can potentially be applied to improve learning assessments across a range of disciplines. The research questions and methodology is presented next, followed by key findings and discussions that will serve as a forerunner for a larger intended piece of research.

Research questions

The emphasis of this study is on investigating the tool usage patterns and information behaviour of students in the context of their learning needs in online academic environments. Research questions were as follows:

- What information tools do students select and use in the context of online assessment activities, and how does this information tool selection and resulting behaviour affect assessment task completion?

- To what extent can the structure and design of online assessment tasks be used to influence the selection and use of information tools and the resulting information retrieval?

Methods

The study was undertaken at a regional university in Australia. Due to the constraints of the summer session for on-campus classes and for convenience, a transition-to-university class was selected in the education school as the students were located on the same campus as the usability laboratory. Ten participants from this class volunteered to participate in the study held in the lab and completed two online assessment tasks. Thus the sample comprised of novice learners who were just getting used to higher education learning environments. Ten was deemed to be an adequate number as Nielsen (2012a; 2012b, Chapter 1) sums up twenty-three years of usability research experience by stating that a handful of user is sufficient in usability studies to identify the big picture.

The study used a mixed methods approach, using digitally recorded observations and retrospective interviews. The recorded observations included every computer based interaction of participants during a usability session, and included the capture of all screen activities and eye movements happening on the computer screen so that the user behaviour could be fully documented and analysed. The online sessions were also watched in real time by the researchers on an adjoining computer. Screen activities captured included the applications used, Web pages visited, documents browsed, mouse and keyboard actions and any words spoken. Eye tracking was done using a Tobii X120 system where all eye movements on the computer screen were made visible in the digital recordings by Tobii Studio software.

Immediately following the tasks completion a short retrospective interview was held with the participant to gather more information on the observed information tool use and search/browse activities in the usability session. Moreover, the participants were questioned about their usual information searching practices and any disparities between the observed and reported behaviour were queried.

The online assessment tasks designed for this study were additional to the required assessment items for the class but modeled similarly and were very concise. Exact task descriptions are attached in Appendix A of this paper. Both tasks required students to search for required information online using any preferred search technique on the Internet and use the discovered information to answer a couple of short questions. Task 2 additionally required that students choose a specific blog or a video to find the necessary information. Student participants were required to provide short answers to the questions posed in the two tasks during the session so that the researchers could assess the quality of response.

The recorded observations and interview transcripts were analysed by conducting a constant comparative audit of data to discover emerging themes as per the grounded theory approach ((Strauss and Corbin, 1998) as described and elaborated upon in Pickard (2013, p. 269-273)). Thus the data was conceptualised into key categories and themes as the analysis progressed. Two researchers and a research assistant individually initiated open coding by examining and developing rules for coding the data, and assigned codes as descriptors of data elements. Therefore, the discovered categories were easier to identify and the process of axial coding was carried out to link the categories with emerging themes. The three coders met as a group several times to compare their codes and the coding rules, and to refine and agree on the terminology used. Emerging categories and themes were discussed at length among the three coders as the clustering of codes continued to happen around the categories. Finally, the selective coding process allowed a 100 percent agreement to be reached on the following four themes:

- Question analysis

- Information tool selection and manipulation

- Information searching, management, and retrieval

- Information synthesis for answer formation

Several limitations are noted for this pilot study: the use of a transition class, concise assessment tasks and the decision not to use timing data. The issue with transition students is that most of them will not have experienced, or been mentored in the use of, academic search techniques nor in the use of available information tools. Hence some of the reported behaviour may differ from students who have studied at a university for at least one full year. Another limitation of this study is that concise online assessment tasks were used under time pressures, and these tasks were not required or compulsory assessments in the subject. Therefore, the results of this study may differ when full length required assessments are used under fewer time constraints. A third limitation is that detailed timing data from the eye tracking system were not considered for analysis, rather the observations recorded during the sessions were analysed as seen by the researchers' in the form of a digital video. This method is different from having a set of fixed texts being read by all participants, as is done in some eye-tracking studies to compare and contrast eye gaze data using mathematical/statistical techniques. Such a comparison was not possible because participants were free to initiate and conduct research on the prescribed topics in any manner they chose to do so. Therefore, participants chose their own tools and Websites, and created their own search paths using the Internet. A final note is that the focus here was to distinguish distinct patterns of information behaviour in online academic learning environments rather than trying to determine attention spans or develop mental/cognitive processing models, which typically characterise psychology studies.

Results and findings

Question analysis

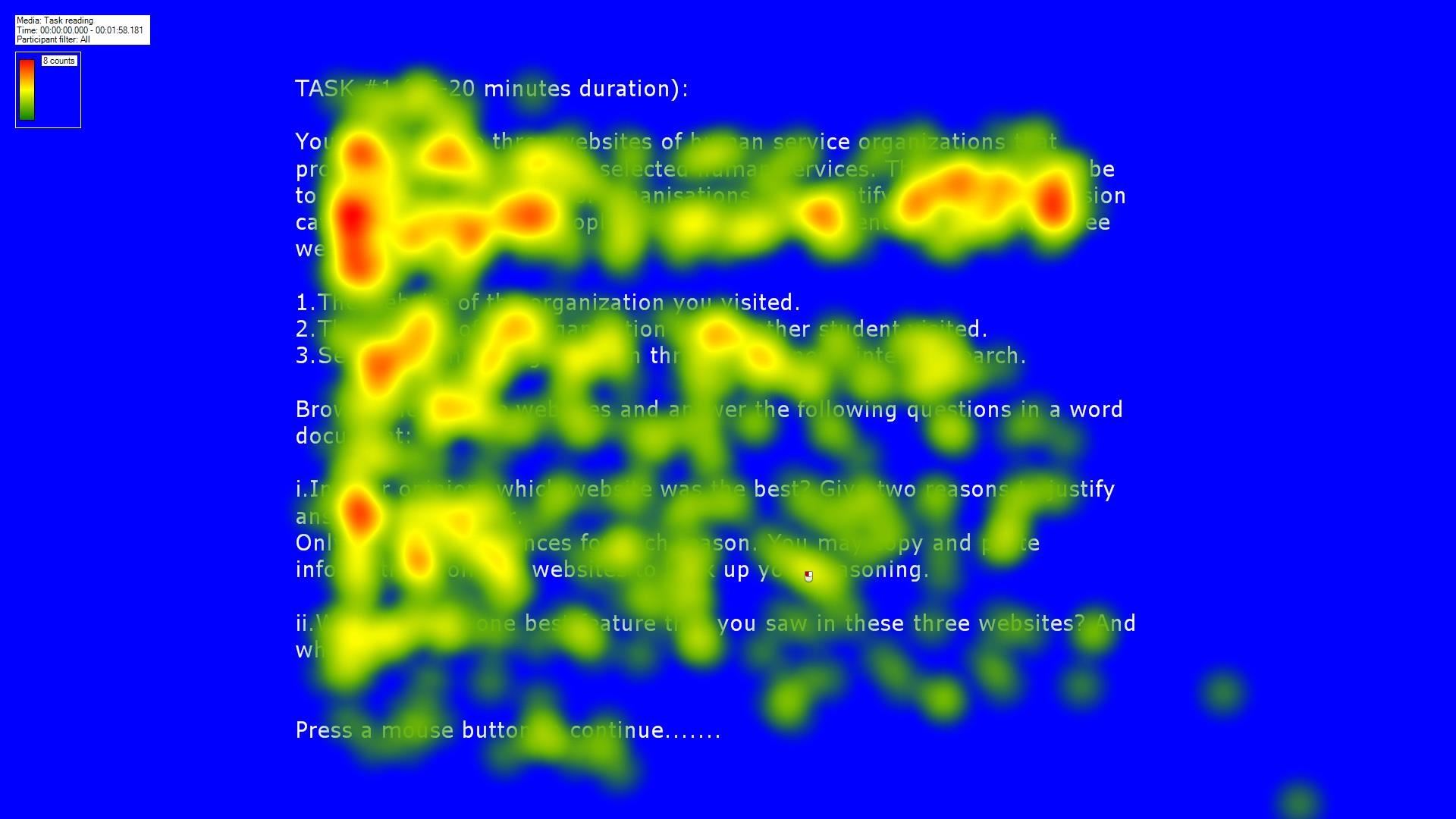

The recorded eye movement/tracking data showed that the task objectives for task #1 were more carefully read compared to the requirements stated below it, and the deliverables at the bottom of the task were mostly skimmed. A heatmap showing the reading pattern of four participants is shown in Figure 1, which conforms to the typical F-shape pattern of Web reading documented by Nielsen (2006). The difference is that the F-shaped pattern only seems to hold for the first reading, and the participants were observed to revisit the task description quite frequently later on to focus on the requirements and deliverables.

On average, the participants spent approximately thirty seconds reading the task description for the first time. This short interval may be the reason that on at least twenty-nine occasions the participants went back to re-read the question (average of approximately three revisits per participant). A couple of participants stated in the interviews that they like taking a printout of the question before doing the assessment online but most other participants appeared comfortable in doing everything online.

There were three participants that continually asked for confirmation about their interpretation of the task from the researchers and when queried about this during the interviews, they attributed the disruptions to their need to reach out to others while working online. For example, one participant stated that

(Communicating) just through our personal emails and, yeah, sometimes the teachers will put up stuff for us that she thinks is important or might help us with an assignment on the forums [P07].

Such behaviour is indicative of the use of frequent messaging among students, as discovered by others, for example (Kennedy et al., 2008; Margaryan et al., 2011), though in a slightly different manner as participants decided to grab this opportunity of having a perceived academic nearby.

Information tool selection and manipulation

From the interviews, popular information tools that most people stated they use were Google, Google Scholar, YouTube and Wikipedia. Information tools in this study have been defined as a computer based application that students use to find information over the Web. Therefore, participants frequently referred to having used these information tools to find information on the Web related to their academic learning environment. Use of subject specific learning management systems was not explored in this study as it was assumed that all students would use those for academic tasks, as has been shown in previous research (Kennedy et al., 2008; Margaryan et al., 2011). One surprising omission from this popular tool list is the library catalogue, which attracted limited attention as discussed further below.

The recorded observations in this research clearly showed that Google was the preferred information tool for this learning exercise with forty-three use instances recorded as shown in Table 1, confirming previous research indicating Google's popularity (Weinreich et al., 2008) and established that users will indeed gravitate to a commonly used simple working solution/behaviour (Bennett and Maton, 2010; Margaryan et al., 2011).

Several interesting explanations emerged when users were questioned about the observed tool usages during retrospective interviews. One user summed up the search sequence by stating,

Normal way of approaching an exercise… start with Google to get a basic understanding of the information, and then I use a mixture of Google scholar, or I will rent books from the library [P03].

The differences between the popular tools Google and Google Scholar were elaborated upon very eloquently by another user in this remark,

Google Scholar doesn't work if you don't understand what you're looking for or you don't understand the topic but Google gives you sort of a broad range of what you need to know and then Google Scholar will give you all your peer reviews, what specific information that you need [P06].

The other popular tool mentioned by 6/10 participants was Wikipedia, as it provided an overview of the topic that they could explore further despite the fact that its use is discouraged in academia. One user explained its popularity:

Because it [Wikipedia] gives me a very broad overview of my topic. I can't quote it. I can't use it because it's not a very reliable source, but it does give me a very general idea [P01].

Recorded observations showed very little use of the library catalogue or its databases, and the reason apparently was that users did not perceive it to be useful for these short online exercises. Though a few participants did recognise that access to articles shown in Google Scholar searches were from their own library. The ease of use and popularity of Google Scholar is the stated reason,

It's just I like the simplicity of it [Google Scholar], and it gives you good results generally [P02]

and

If I can't find what I'm looking for in Google Scholar, I'll search through them [library databases], but otherwise I just use Google Scholar mainly [P08].

However, when asked about their preference with longer learning exercises, that perhaps require an essay to be produced, 5/10 participants stated their preference to search for books and resources using the library's Website.

Other information tool use instances observed were for YouTube (5), social networking (1), blog (1) and somewhat interestingly, trusted organizational sites (4). It was interesting to note that even though the second task required use of a video or a blog, participants preferred Google over YouTube as an information tool, thus casting their information seeking net wider. Interviews revealed that videos were perceived to be good for only some specific instructional tasks (do it yourself or science projects for example) and text was generally preferred for academic learning. One comment in this regard was,

I usually just use like reading material. I don't use videos all that much… I just usually like read stuff, unless a Website links like a really good documentary or something I might have a look, check it out, and see where it leads [P04].

Another problem was identified by one user as video generally not being searchable,

I thought that [the information search] could take a long time finding a suitable video, going through them [P03],

and

sometimes you go through a million videos just to find one and it'll be like right at the end of the pages that you have to search through, which is really annoying [P08].

The latter participant also suggested that categorisation of YouTube videos should happen to assist in information searching and make it a better tool.

No use of social media was observed in this study and interviews indicated that it was generally perceived to be a good information tool for personal communications only, and not useful for academic work. For example, Facebook was generally not considered an academic information tool, as indicated in this remark,

Anyone can put anything on Facebook and I suppose that's the same with YouTube as well, like it's not like known to people in our generation as an academic resource [P02].

This attitude persists despite the fact that Facebook was being used for resource exchanges related to the subject and the course, as suggested by this participant,

We had an exam yesterday and before we got on everyone was sharing information, posting pages, asking questions, which is what we [usually] do [P01].

The distractive aspect of social media was also highlighted by 2/10 participants, and one stated,

Oh well, for personal it's different but not when I'm looking for academic stuff. Although people do say when you're trying to get work done, it's generally 90% Facebook and 10% whatever you're trying [laughter] [P10].

Reliability and trust is another issue that hampers the use of social media and public blogs among this novice group of students as they struggle to find quality material for their academic work. Therefore, participants voiced concerns such as,

Because I don't find it's [social media] like, reliable. Anyone can just write something on there and you can believe it and then the teacher will be like,'Well, that's not right. Where did you get this source from? [P07],

and,

Yeah, I don't know because anyone can write them [blogs] so, who knows what's on them and whether you can trust it anyway [P10].

Finally, this technologically informed generation of newcomers to university generally found all information tools easy to use, and during the interview, almost all participants expressed no issues with the tool interfaces as suggested in this remark,

They [information tools] are all pretty similar. Like, Google and Google Scholar are very similar because they're run by the same company. Sometimes YouTube, when you type in things to search, it comes up with stuff that you just don't even want and you're like, 'No' so you have to try and word it correctly to search for the specific thing that you want so that's probably one of the main points but that's all really [P07].

Browser tabs to keep multiple windows open simultaneously were also used by almost all the participants (8/10) to keep their searches organized when searching for information.

Information searching, management and retrieval

Information search

Observations from eye-tracking data of participants' searching behaviour uncovered some interesting findings that are displayed in Table 1. The first value listed indicates the number of instances observed, while the value in parenthesis indicates the number of distinct participants who engaged in the observed activity. Reading has been termed as careful when the red dot generated by the eye tracker, indicating reader's gaze direction, was observed to travel on the text slowly as the reader read most words. The term skimming, or speed reading, has been used when the reader's eyes were observed to travel through the content really fast, and it was determined by the researchers that the reader could barely grasp the gist of the narrative, let alone fully comprehend it. Scanning is used when researchers observed the reader's eyes bouncing around on the page without any focus, and often with little or no direction.

| Uses Google for searching | Uses browser search bar | Careful reading | Skimming (speed reading) | Scanning or bouncing on page | Skip paid ads | Giving up | Choosing from first few results | Choosing from lower half | Going to second page |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 43 (9) | 5 (6) | 0 (0) | 15 (9) | 7 (6) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 12 (9) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

Table 1 results indicate that Google results were hardly ever read as participants tended to skim (speed read - fifteen instances observed across nine of the ten participants) or scan (bounce round the page - seven instances observed across six of the ten participants) the results page. Most participants (nine out of ten) looked at and chose from the first few results (twelve instances) indicating a very much targeted search, and only one person bothered to scroll down and look at the lower half (one instance) of the page to choose a link. None went to the second page of search results or even looked at it, while two participants just gave up on the search entirely after not seeing seemingly anything of relevance on the upper half of the first page.

| Refines search query | Types in exact target URL | Random flipping between sites | Returns to visited sites for information |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 (7) | 3 (3) | 8 (5) | 6 (3) |

As shown in Table 2, the participants did modify their search terms at times (twelve instances observed across seven participants), but mostly preferred to go with the results returned from their initial query. Three times an exact URL was typed in for known sites while three people went back to some already visited site twice to get new information for another purpose. Finally, being novice academic users, five participants engaged in eight instances of random flipping between sites they opened using the browser's tabs without indicating any engagement with the content, as if hoping that an answer to the query will jump out at them.

Information browsing and retrieval

Presented in Table 3 are observations from eye-tracking data, starting with the browsing and reading of a Website's content. An extraordinarily large number of instances (fifty-one) across all ten participants are noted where the readers' eye gaze quickly moved about on the Webpage in a seemingly random pattern without focusing or pausing on any particular text or image. There were only fourteen instances where eight of the ten readers paused their scanning to carefully read some piece of text. Seven of those instances happened while the reader was at the beginning of the page, and only four participants did this. Only two participants went for a reread (once each), but that is understandable given the perceived shortage of time.

| Careful reading and pausing | Skimming or speed reading | Scanning/ bouncing on page | Using site menus | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14(8) in main content | 7(4) only in beginning | 2(2) when rereading | 13(7) in main content | 13(8) in titles | 3(2) in lists of weblinks | 51(10) | 9 times read carefully | 12 Skims | 5 Scans |

In addition to the data shown in Table 3, there were a further twelve noted instances of skimming to seek further information when participants revisited a site, which in itself happened occasionally (only twelve times by six participants). Interestingly, whenever a participant went back to look at a site, they mostly scanned or bounced around on the page without seemingly any reread. When queried about this trend in interviews, the use of skim or scan was justified by participants as being necessary to pick up keywords. For example, one participant stated,

If you can scan it quickly and try to pick up, or know, keywords and information to help, you know, what you know, what you are looking for, yeah [P02].

Observed use of site menus showed more focus and concentration by users as many either carefully went over the menu items (nine instances) or at least skimmed them (twelve instances) to get an idea of the layout of the whole Website and the sort of content they will encounter on it.

Even for these short tasks where the participants knew they were being observed, there was one instance of distraction where the participant followed an unrelated link. This diversion was justified during interview as,

Sometimes I get bored and I just sit on YouTube and it's really convenient because if you just go through the side bar you can find relevant things. Like if I look up how magnets work I can end up learning how black holes work or why giraffes have long necks because that's what YouTube does [P01].

| Carefully watching photos and videos | Skim images | Scan (bounce) around images | Image/video captions and titles (skim/scan) | Watch full videos | Watch partial videos |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 (6) | 3 (2) | 5 (3) | 7 (4) | 3 (2) | 3 (3) |

A category of visual learners emerged from the data in Table 4 as a segment that engages more with the images than text. It was observed that six participants looked intently at images fifteen times during this research, and one of them justified these actions in the interview by stating,

I like looking at pictures. I like seeing what people are up to ... I think I learn more visual[ly] so I like looking at more the visual pictures and all that rather than just looking at the writing. It bores me out [P07].

Information synthesis for answer formation

The browsing behaviour identified above in Table 3 leads to another layer of information refinement when associated with the participants' answers to the questions posed in the two tasks. The researchers graded participants' answers into three categories, poor (few components of the tasks were answered), reasonable (most of the task components were answered with some justification) and good (most to all of the tasks answered and justified). In Table 5 the observed behaviour is matched against the graded responses, where good response came from only one student who intently compared content on the various visited sites and read slowly.

| Seeks confirmation from researchers | Random skipping between sites | Comparing content on sites | Reading slowly | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor response | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Reasonable response | 1 | 0 | 11 | 2 |

| Good response | 1 | 0 | 14 | 7 |

In addition to this information, elements of slow reading and re-reading also point to a better achievement by the student. It is surprising that as indicated in Table 6, four participants managed to form a response without even finding the required information. One excuse offered was,

it [the discovered information] wasn't exactly what I was looking for, but it sort of stressed the importance of the childhood and stuff. So it sort of, like, it just backed what I was trying to say. Didn't really provide new information though [P04].

| Forming response from memory | Quick look back to seek justification(s) | Changed answer after look back | Formed response without finding required information | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 (7) | 1(1) skimmed on return | 11(5) scanned on return | 1 (1) | 4 (4) |

Table 6 also indicates that there were twelve observed instances by five participants (half of sample) of returning to a Website to look for further information to justify a response while an answer was being formed. On most of these return visits the visitors simply scanned the page(s), except one participant [P10] who skimmed or speed read the content. Only one participant [P06] made changes to the response based on the revisit. Almost 50% of the time (nine occasions out of a maximum possible of twenty), seven participants formed a complete answer without revisiting any site even once.

Discussion

The two basic components of eye movements are called the saccades, when eyes are moving, and the fixations, when the eyes remain quite still and focused so that new information is acquired (Rayner, 2009). As the results of this study indicate, most observed eye-tracking behaviour consisted of saccades rather than fixations, which were mostly observed when people paused to look at pictures, or when they were watching videos. So did the participants acquire the required information during the saccades witnessed in this study? Raynor concludes that although no new information is encoded during saccades, there is some cognitive processing happening in most situations while people read text. This conclusion is partly based on Irwin's investigations (1998), which established that lexical processes (defined as processes devoted to word recognition and word identification) continue during the saccades, or while the eyes are moving, as indeed this study's results tend to demonstrate.

The first research question posed was:

1. What information tools do students select and use in the context of online assessment activities, and how does this information tool selection and resulting behaviour affect assessment task completion?

First is the focus on the selection and use of information tools. Results of this study indicate that Google remains the preferred option as an information tool and as a trusted search provider where students still retain full faith in the top results it produces (Qayyum and Williamson, 2014). This finding is contrary to what Head (2007) reports for regular four- to six-page-long assessment tasks. Other popular information tools like Wikipedia and Google Scholar were usually discovered through the Google search engine, and students preferred to use Wikipedia initially to gain some preliminary understanding of the topic under discussion. Information tools containing video files, such as YouTube, or blogs/social media were usually not very high on the student's priority list of sites to visit as they were either not deemed relevant, or required too much time to search/view (as in videos), or not considered trustworthy in a public environment (for social media) as indicated also by Liu (2010). Social media in the form of Facebook was being used for some question and answer activities with little academic use; a finding which agrees with previous research (Hrastinski and Aghaee, 2012).

Google Scholar seems to be the preferred option as an information tool over the traditional library catalogue for article searches simply because of its ease of use in online assessment tasks such as the one used in this study. Indeed a study of user preferences at the University of Mississippi (Herrera, 2011) indicated a steady increase in students linking to the library databases from Google Scholar. The participants did mention that they still use the library catalogue to find books, but that trend may not hold if Google Scholar or some other provider comes up with an easier interface in future and renders the library catalogue visit-less, especially by these new university students.

Another potential information tool was revealed when four participants opted to keep a particular Website open at all times and followed links from that Website, thus using the discovered site as an information tool. From the literature, McClure and Clink (2009) explored increasing student use of Internet sites and lists popular sites being cited in student essays as being news sites, sites run by advocacy groups, government sites, informational personal blogs etc. Therefore, sites acting like Web portals, and containing a great deal of information and associated links to further resources, are important information tools that students use during routine information search and retrieval. The participants in this research mostly stumbled upon such sites through Google searches, and decided they could be trusted and were worthy of further attention. For example, one popular site as an information tool was that of the Department of Education of New South Wales, which was deemed relevant and useful for this exercise by the participants.

The use of browser tabs to keep their information tools and associated searches organized is similar to the finding of Weinreich et al. (2008), which showed that users on average maintain 2.1 open windows when searching for information. Though, as Weinreich et al. rightly point out, this average is greatly influenced by high tab-users compared to users who do not use this useful feature at all in their work (for example two non-tab-users in this research, or 20%). This issue points to a need for training new students in the organization of information tools so that they are better able to undertake their routine academic learning work. Such a training exercise can also improve the online multitasking abilities of students to tackle the issue of online distractions as pointed out by Subrahmanyam et al. (2013).

This research indicates that observed and recorded use of information tools by students was at a basic level in this study and mostly conforms to the prevalent technology usage trends (Kennedy et al., 2008; Margaryan et al., 2011). As Margaryan's research also indicates, the higher education teaching staff are now routine users of prevalent technologies and are therefore not speaking a different language compared to students, as suggested by Prensky (2001) some years ago. As a result, the conclusion drawn here is that university educators designing online learning activities today are very much in harmony with the technology used by students and therefore educators should keep in mind the popular information tools bound to be used by the students while designing assessment items. Such a design criteria will help them identify some useful tools for the students in the assessment guidelines, which will guide the students towards better and more relevant information resources.

The information tools related behaviour revealed in this study mostly included the search patterns and browsing and retrieval activities of students. Eye movements showed that the participants rarely scrolled down the Google search page, a trend similar to what Weinreich et al. (2008) discovered when analysing the Web logs of 25 participants. The information seeking patterns using Google also indicated some superficial search techniques, which Callinan (2005) states are poor orientation skills usually demonstrated by first year students. Research skills are developed, according to Callinan, as students progress through different levels of subjects with increasing academic expectations. These participants wanted their answers quick and fast from Google, as reported also by Thompson (2013), and this research indicates that they did not spend much time to focus on discoveries and did minimal refinement of search terms. Similarly, Rowlands et al. (2008) point out that this speed of young people's Internet searching means that little evaluation of discovered information is carried out for relevance, accuracy, or authority. That finding is comparable to the behaviour observed in this research as the quality of task responses was often mediocre for most of the participants who displayed poor speed reading behaviour.

When it came to reading the content on discovered Websites, eye tracking observations indicated a big trend towards speed reading, scanning or bouncing around on the Webpage rather than careful reading. Such a behaviour is now the norm with so much information available on the Web and users typically spending less than twelve seconds on a Webpage (Weinreich et al., 2008). How much of that short visit translates into actual cognitive processing of information is yet to be explored. It is assumed that some lexical processing of information is happening during these periods of saccades, as demonstrated by Irwin (1998), and therefore this research recommends that the novice students need to be taught techniques to help them improve their online speed reading abilities, thereby achieving the lexical processing abilities needed for a university level education. Such training will help educators achieve a significant impact on successful completion of online assessments.

While it was not possible to come up with a comprehensive heatmap to compare with Nielsen's (2006) F-shape reading pattern because of high variation in Websites visited, eye movement observations clearly indicated that users in this study looked more often at the content on top of the page, and mostly skimmed or sometimes even ignored anything in the middle or lower parts of the Web pages. These patterns conform to the satisficing behaviour observed when users read pages of linked text as in documents (Duggan and Payne, 2011) and text placed earlier on in Web pages is read more often compared to anything placed lower. Scrolling down a page adds cognitive load on Web users (Weinreich et al., 2008) and observations here indicate that people will generally avoid scrolling. Therefore, the behaviour of the students when they use the identified information tools leads to another recommendation that novice readers, such as the first year university students, need to be trained in information tools usage and Web literacy techniques to help them find and absorb maximum possible information. These findings complement and extend Head's (2007) findings that students are not always sure of what is expected of them, and how to conduct research for assessment tasks. The impact on successful assessment completion should therefore be significant as a result of adopting these changes in assessment design.

The second research question posed by the study was:

2. To what extent can the structure and design of online assessment tasks be used to influence the selection and use of information tools and the resulting information retrieval?

The findings of this pilot study illustrate information tools related behaviour that demonstrates a range of sophistication in search techniques, and the interpretation of tasks and evaluation of search results for answer formation. For example, the lower end of sophistication is indicated in the second task, which required that the students look up a blog or a video. Most students took the perceived easy option in this task and looked for a video instead of focusing on the fact that a well written blog with many entries could possibly provide them with better learning. This is despite the fact that most stated in the interview that a video was not their preferred option of searching for information, so use of videos in this study was done simply for convenience. Another example of low sophistication is that of Google as the most preferred information tool, though sometimes participants used organizational portals that they had discovered for the first task as an information tool. At the higher end of search sophistication behaviour, many participants neatly organized discovered sites and information tools in open tabs within a browser and, while forming the answer, they took a quick look back at the open tabs to confirm what they were writing. Such an action helped them remember the content and any action they performed at a particular site, as demonstrated also by Weinreich et al. (2008).

However, characteristics of higher order thinking were minimally apparent when the participants compared various Websites in the first task. Such a behaviour is suggested in the literature also (Hung, Chou, Chen and Own, 2010; Kirkwood, 2008), and this research indicates that it points to poor information evaluating and analysing habits of participants when they form their answers. For example, nearly half of participants returned to a Website to look for further information to justify a response. But eye tracking trends indicate that most of these returnees simply scanned the page(s) upon revisit, except one [P10] who skimmed or speed read the content. Only one participant [P06] made changes to the response based on the revisit(s), indicating that for most just the look and feel of Websites provided enough confidence that cognitive thoughts and memories captured the first time around had been revived.

The various student behaviour discussed in this section clearly illustrate that students were not maximising the information search capacity of the information tools available to them, and this in turn was hindering the quality of information synthesis done by the student. Goodyear and Ellis (2008) state that online material, or material using the Internet should be sufficiently structured so that students are engaged and know how to approach the particular learning required. No tools related information or scaffolding were used in the tasks in this study and indeed, as Head's (2007) research indicates, many of the undergraduate assessment tasks they analysed lacked necessary guidance and details for students on conducting quality research. Therefore, a recommendation for assessment designers is to scaffold from shortest to the longest of the online assessment tasks, and also bring student's focus to the information tool(s) that will provide better research and learning experience, keeping in context their study level/subject.

Conclusions and future directions

The foremost observation is that online assessment tasks should be structured better to contain some information tools related information and scaffolds for searching and reading. Discussing these things in a traditional classroom setting, as recommended by Li (2012), is not possible in distance settings and may even be overlooked by classroom instructors. Therefore, task structuring should happen in all settings, including pointing students to Websites that package relevant information and associated blogs, and other relevant information tools. Specific guidance such as this in the task should assist students in selecting better tools and avoid lapses as were made in the second task, which required students to look for a video or a blog and students sought convenience over learning by looking for videos. Scaffolding assessment is recommended also to improve their depth of learning as students will engage with the online content and remain connected with the task during their thinking and learning process. A good scaffold in tasks should also reduce behaviour such as aimlessly flicking between search results without reading the content, or relying on others and asking for their interpretation of the question. Finally, on the student's side, teaching multitasking techniques (such as organizing information tools and search results in open browser tabs) and a focus on developing speed reading and information literacy practices will help them improve their online information seeking, reading, comprehension, and multitasking abilities.

These findings provide a foundation for a larger study to examine student responses for a required online assessment in their own work settings and recording their behaviour using wearable tracking devices. Such an extension will seek to confirm and build upon the findings of this study and add to the knowledge base about online learning behaviour by providing a further insight into the structure of online assessment tasks, use of information tools, and student behaviour.

Acknowledgement

The project was funded by Research Priority Areas grant from the Faculty of Education at Charles Sturt University.

About the authors

Muhammad Asim Qayyum is a Lecturer in the School of Information Studies at Charles Sturt University, Australia. His research interests include information needs and uses, knowledge management, and lately a focus on the use of technology in education to improve human computer interaction. Asim can be contacted at aqayyum@csu.edu.au

David Smith is a Course Director in the Faculty of Education at Charles Sturt University. His interests include the integration of technology in learning and and the effective implementation of eLearning strategies in the education and training sector. He can be contacted at davismith@csu.edu.au