Questioning strangers about critical medical decisions: "What happens if you have sex between the HPV shots?"

Lynn Westbrook and Yan Zhang

School of Information, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, 78701

Introduction

Each year, about 12,000 women in the United States get cervical cancer (Centers for Disease Control and Protection, 2014a ), the second leading cause of cancer death for women in the United States (Walhart, 2012 ). In 2010, the most recent year for which numbers are available, the U.S. had 11,818 cases and 3,939 deaths (Centers for Disease Control and Protection, 2014b). Regular Pap tests have contributed significantly to the reduction of cervical cancer deaths over the past several years. Due to the development of two vaccines against the sexually transmitted disease human papilloma virus, the most common cause of cervical cancer, it is now the most readily prevented of all women's cancers. The vaccines (Gardisil, approved in 2006 and Cervarix, approved in 2009) are given in a three-shot series (ideally, before puberty) to provide maximum protection. In women of any age who do not have the human papilloma virus, the vaccine should prove equally efficacious. In addition to being increasingly preventable, cervical cancer has such a slow growth rate that regular screenings can often save the lives of those for whom the vaccine comes too late. The vaccine is also approved for boys and men, protecting them from the human papilloma virus and its potential results, i.e., the anal and throat cancers that can develop from specific sexual activities with anyone who has the human papilloma virus. And, of course, having boys and men protected against the human papilloma virus helps protect the women and girls with whom they interact.

The risk of getting cervical cancer starts before puberty and continues through end-of-life. The disease is embedded in the social stigma of a sexually transmitted disease; it involves both social and medical relationships. Generally, people want anonymous and personalised information on these subjects. Authoritative online resources, such as the National Library of Medicine, provide extensive pre-packaged materials but deliberately decline to answer individual health questions. Customised responses to health questions could come from healthcare professionals, as well as certain social media platforms, such as crowd-sourced question-and-answer forums. The latter presents social media questions on users' health information needs (Zhang, 2010), posted by those for whom such internet use and access is viable. In this study, we analyse individuals' cervical cancer questions posted in a public question-and-answer forum, Yahoo! Answers, to generate insights into how consumers conceptualise their cervical cancer information needs and how those needs relate to each other. Unlike health issues commonly discussed with strangers (e.g., flu, broken arm), cervical cancer's role in the taboo topic of sex acts generally requires an appropriate relationship (e.g., medical personnel, family, or friend) to generate a sufficiently comfortable context for expressing information needs. This study's results can improve the understanding of women's informational struggles in more private medical situations.

Literature review

Medical information seeking

For many in technologically augmented societies, the internet is now a standard source for health information (Fox and Duggan, 2013). It provides both static information and interactive forums on subjects as varied as a specific disease problem, medical procedures, weight control, health insurance, food safety, medical test results, gene therapy and intersections between sexually transmitted diseases and cancer (Oh, Zhang and Park, 2012; Fleming, Chalmers and Wakeman, 2012; Fox and Duggan, 2013; Yoon and Kim, 2014; Bowler, Mattern, Jeng, Oh and He, 2013; Oh, Jeng, He, Mattern and Bowler, 2013; Robillard et al., 2013). Indeed, for some individuals, it fuels cyberchondria, in which high levels of health anxiety lead to excessive online searching (Fergus, 2013). Given the significant impact that health information seeking has on various aspects of human life, it, as a context area in general, merits close examination.

Women are quite likely to (a) search for health information online and (b) use multiple sources, both formal and informal, in combination (AlGhamdi and Moussa, 2012; Blanch-Hartigan, Blake and Viswanath, 2014). When seeking information for intimate personal health issues, such as menopause and fertility, they tend to favor respectful community norms, privacy affordances and factual data (Genuis, 2012; Slauson-Blevins, McQuillan and Greil, 2013). Simultaneously, women value direct and interpersonal support. For example, Kratzke, Wilson and Vilchis (2013) reported that when using mobile technologies in breast cancer information seeking, rural women prefer direct, interpersonal cell phone communication over texting in any format. As might be expected therefore, women tend to feel comfortable in using social media platforms for health communication, including for cervical cancer information (Thorburn, Keon and Kue, 2013; Tran et al., 2010; Koskan et al., 2014).

Social media forums, such as Facebook and YouTube, are abundantly supplied with cervical cancer information (Lyle, Lopez, Pasick and Sarkar, 2013), the information need focus in this study. For example, shortly after their rollout, the new vaccines were the most commonly discussed vaccine on YouTube. A little over half of the videos (55.6%) were positive; 11.1% were industry-sponsored messages deliberately crafted to present the vaccines in a positive light. Notably, 66.7% specifically referred to the relevant drug companies, Merck or Gardasil. Most videos were substantiated by regular reference to cervical cancer's role as a serious disease prevented by the vaccine (Keelan, Pavri-Garcia, Tomlinson and Wilson, 2007). The diversity presented in the information in social media invites examination the nature of information on such platforms. This study takes question-and-answer user-generated questions as reflective of information needs (Taylor, 1968).

Just as information is abundant, so too are women's cervical cancer information needs. For example, interviewing women who had been for cervical screening or a colposcopy, Goldsmith, Bankhead, Kehoe, Marsh and Austoker (2007) found that most patients had no prior knowledge of the human papilloma virus. The U.K. national screening programme leaflets left women with more medical questions than answers. Particularly valued were basic explanations of the human papilloma virus detection, infection, transmission and prognosis. McCaffery and Irwig (2005) reported similar findings on the human papilloma virus viral types, implications for sexual partners, prevalence, latency, management options and risks. The vaccines' efficacy and risk level continue to provoke questions (Allam, Schulz and Nakamoto, 2014; Wong, 2014) as do moral value considerations in preparing pre-pubescent girls to avoid sexually transmitted diseases (Hilpert, Brem, Carrion and Husman, 2012). For cervical cancer patients, however, the most common information matters were diagnosis, stage, prognosis and self-care techniques (Noh et al., 2009).

As this review suggests, the broad areas of women's cervical cancer information are increasingly documented however, little is known about the characteristics or the nature of these needs. Thus, our primary goal is to understand the characteristics of users' needs expressed on question-and-answer platforms.

Question-and-answer sites as a health information resource

The clinical credibility of question-and-answer responses remains a substantive concern (Bowler et al., 2013; Fichman, 2011; Oh and Worrall, 2013). For example, answers to eating disorder questions posted on Yahoo! answers rarely used evidence-based medicine or credible sources (Bowler et al., 2013). Consumers regarded answers' quality more highly than did librarians and nurses, indicating concerns regarding consumers' ability to critically evaluate health information (Oh and Worral, 2013).

Despite such concerns and a desire for privacy, consumers' question-and-answer questions tend to reveal a great deal of personal data, including demographics (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, geo-location), medical situation (e.g., symptoms, diagnoses, treatments, medical test results) and psycho-social explanations (e.g., emotional states, health insurance) (Zhang 2013). Many questioners struggle with medical terminology and frame their medical information needs in terms of negative emotions (Oh et al., 2013; Zhang, 2010). When asking questions with socio-emotional aspects, they often provide personal narratives centered on past experiences and affect (Oh et al., 2013).

These studies suggest that question-and-answer platforms provide a valuable opportunity for better understanding authentic consumer health information needs and concerns. In this study, we will focus in on women's deeply private and potentially high-risk posts concerning cervical cancer through an exploratory analysis of consumer-generated questions posted on Yahoo! Answers, the most popular social question-and-answer site in North America.

Research questions

Information needs posited as natural language questions generally convey the topic and, in some cases, the type of information needed. Many even illuminate users' understandings of their current problems as related to their information search (Taylor, 1968). Our goal is to better understand the characteristics of users' information needs concerning cervical cancer as presented in natural-language questions posted on Yahoo! Answers. To that end we examined the subject and type of information requested, as well as information that users provided to set up the stage for their inquiries. More specifically, we addressed the following research questions in the context of cervical cancer in a question-and-answer forum:

- What are the subject matters of posts?

- What types of answers are solicited?

- What information do posters provide with their requests?

- How can these information needs be characterised?

The first three questions are descriptive, the answers to which are intended to give sufficient context for the fourth question, which is of an interpretive nature.

Research method

To gain an in-depth understanding of users' requests, 250 viable messages were studied using the qualitative content analysis method (Zhang and Wildemuth, 2009) wherein themes emerged from the data. In March 2013, a script was written to crawl the health category of Yahoo! Answers using their API and pool the most recent 2,500 messages containing the phrase cervical cancer. Posts in which no actual question was stated were removed. Of the remaining messages, 250 were randomly selected.

The first 50 messages were used to develop the coding schema. Meeting regularly over several weeks, the authors and a GRA worked collaboratively to generate and organize a codebook complete with definitions and examples. The coding is focused and guided by our research questions. That is, we attempted to code the subject (e.g., treatment, diagnosis and symptoms), type (e.g., factual information, advice and personal experiences) of information requested, the information that users provided to contextualise their requests (e.g., demographic information and emotions), as well as how the needs can be characterised (e.g., by time and by intensity). The group meetings followed a set pattern in which both authors coded the same question independently, results were compared, changes were made in the codebook (if necessary) and the cycle repeated. Five codebook iterations produced a full set of codes in which no changes were required to produce 100% agreement.

Each author then coded 20 of her allocated 100 posts, from the remaining 200 messages. Those posts were then independently coded by the other author and the coding results compared. This inter-coder reliability test reached 96%, more than the commonly required 94% (Miles and Huberman, 1994). In this final review session, the few remaining discrepancies were discussed. No new codes were added and no significant changes were made in definitions. Each of the two coders then completed her set of 100 for a total of 200 coded posts. The 12,668 words in the 200 posts were analysed using 172 codes which were recorded with HyperResearch.

The limitation inherent in this approach pertains to the way in which the posts were selected. Social question-and-answer sites containing a substantial number of cervical cancer queries are readily available, e.g., Wiki-Answers. In choosing one site to work with we missed the opportunity to explore the degree to which, if any, site structure played a role in our research questions.

Results

General demographics of users

Approximately half of the questioners provided no demographic information so the following numbers must not be taken as representative of this sample much less, of course, the entire data pool. Additionally, we took the posters' statements as accurate although individuals could certainly have chosen to misrepresent themselves. Given that critical context, most posts came from females (107) and ten from males. In 17 posts, questioners self-identified as being under 18; in 35, they listed themselves as between 19 and 30 years of age. Posts were primarily for self (135 posts) with 21 posters self-identified as asking on behalf of others. Despite the sexually transmitted disease connection to cervical cancer, only 29 posters self-identified as sexually active while eight identified themselves as not active. In terms of medical condition, questioners primarily identified themselves as having no sign of cervical cancer (104 posts); 36 posts mentioned the cancer in their lives and nine identified it as being in remission. These numbers give a minimalist context for the findings and should not be interpreted from a statistical point of view.

Research question 1: What are the subject matters of the posts?

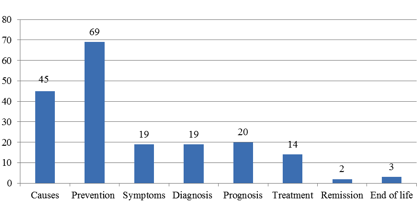

Provided as a single piece of context for this first research question, Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of posts in relation to their explicit mention of the disease process. Prevention topics, including potential causes of cervical cancer and specific prevention strategies, are readily seen as a major concern (57% of all the posts). Although modern prevention consists of both vaccines and screenings, most posts addressed only the former. Other more clinical subjects (including symptoms, diagnosis, prognosis and treatment) received less attention. In addition, several posts, not shown in the graph, asked questions unrelated to the disease process, such as health insurance plans and medical personnel availability.

As with any numerically descriptive data points herein, Figure 1 provides only baseline contextual information. The posting excerpts, however, indicate a strong pattern of placing these disease-centric subjects within the realm of posters' concerns of their sexual behaviour. For example, several posts were generated by multi-pronged education campaigns concerned with female school children taking the vaccine. Particularly, the discrepancy between what some authority figures expect of young females in regard to their sexual behaviour and the reality of their sexual practices underpinned a number of posts on the vaccine.

it said on the leaflet we received at school that [the vaccine] needed to be administered before your daughter (it was aimed at parents) became sexually active. I'm worried because I am already sexually active. Does this mean it won't work? Will it harm me? HELP!

Some posts were driven by highly specific sexual activities.

I Heard that if you're not a virgin, you can't get the cervical cancer injection. What about if you've been fingered?

Across all disease-centric topics, the intensely personal nature of the questions raised the issue of emotional vulnerability in medical information seeking.

Research question 2: What types of answers are solicited?

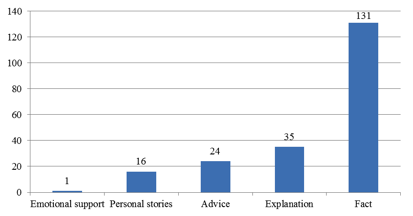

Users elicited five types of answers: emotional support, personal stories, advice, explanation and fact – primarily the latter two (in seven questions, two types of answers were solicited.).

Having a single post explicitly seeking emotional support and only 16 asking for personal stories reflects the norm of this particular social question-and-answer site which does not encourage affectively based questions.

Advice posts guided social interactions with family, sexual partners and friends. Several sought strategies for strengthening and supporting relationships.

How can i convince my ex man that i didn't know i had it or if i gave it to him i didn't know i did ? ?

How do I help my friend who has just been diagnosed with cervical cancer? My friend is 35 and found out yesterday that she has cervical cancer. She says she threw up most of last night (not because she's sick, it's because she's so upset). I know that many people can overcome cervical cancer and that this is a cancer that can be treated. If you have any suggestions on how I can support her, that would be appreciated.

These advice posts on interpersonal connections called for concrete responses rather than emotional sympathy.

Finally, some advice posts focused on medical decisions of life-long impact.

How do you prevent cervical cancer when already diagnosed with HPV? I understand that regular pap testing can prevent cervical cancer when already diagnosed with HPV, but is there anything else you can do with diet or suppliments (for example) that can help prevent the cells from turning cancerous?

The stages of cervical cancer move from the vaccines to screening to dangerous screening results and on into types of treatment. This longitudinal view across stages is uncommon.

Fact posts, on the other hand, sought fodder for decision-making, some of which was quite immediate.

Can we have sex cause we're planning on having sex for the first time Saterday night and I wanna make sure its safe. AND I know that the vaccine doesn't protect against all types of cervical cancer but does it protect against getting throat and anal cancer from having anal and oral sex?

The expectation that high-risk situations are simple enough to be addressed by factual posts reflects the very nature of cervical cancer. Pre-puberty, it's just a matter of a vaccine; post-puberty, it's a matter of survival.

Finally, explanation posts tended to interpret and elaborate on medical experiences.

How uncomfortable were your side effects from radiation therapy? I'm wondering how bad it really feels. I have heard it is like a bad sunburn with blisters... Did you have to wear different types of clothing due to the pain? My radiation is for Cervical Cancer and I'm just trying to get a heads up on what I am really going to feel like and for how long...

All of these question types were characterised by a desire for privacy and a need for immediate response. Posters wanted actual information, not referrals to authoritative sources or bridges to communities, suggesting that practical problem solving rather than general knowledge development is their goal.

Research question 3: What information do posters provide to contextualise their requests?

Posters provide facts, examples, justifications, histories and similar contextual narratives to accompany their actual questions. Some of these elaborations explain the posts' intensity while others extend personal situation descriptions. Telling their own medical story, as well as those of people in their socio-familial groups, questioners lay open a view of their social and medical situations.

Contextualization frequently places posts in a personal context that frames concrete, if not directly relevant, information. Consider the following question that, although it has no simple answer, is posited as susceptible to a numeric response.

How long does it take for precancerous cells to become cancer?

The following augmentation to this question, however, provides additional information that, among other purposes, might be viewed as justification for using the free question-and-answer service and/or providing clues to the intensity of the need.

A few years ago my gyn found precancerous cells on my cervix. My husband lost his job and we lost our medical insurance. How long does it take for precancerous cells to become cancer?

Finally, the this might help get me a useful answer motivation appeared to extend medical history for posters.

I also have two little sisters, if that even matters.

Research question 4: How can cervical cancer information needs be characterised?

Users' cervical cancer-related information needs can be characterised and viewed through the lenses of four types of continua. Several temporal continua place cervical cancer across women's life times. The intensity continuum references questioners' personal determination of a situation's risk level. The sexual behaviour continuum places cervical cancer in relationship to expected, planned and current sexual activity. Finally, the personal agency continuum addresses the questioner's control over cervical cancer.

The temporal continua

Cervical cancer, as a possibility or experience, crosses four temporal continua, two biological and two social. Biologically, from women's perspectives, cervical cancer is part of their lives from the years immediately preceding puberty through menopause and into end-of-life.

I haven't had a checkup since Aug 2003 and I made an appointment for one. First I didn't have insurance and then I was just putting it off. Somehow almost 4 years have gone by. They say that you should have one every 2-3years. Tonight, I caught a med-tv show and this young woman of 23… they found cervical cancer and it was too late to do anything and she died. Now I am completely freaked out! I'm 26. Part of me can't wait and wishes that it was tomorrow and the rest of me is now terrified to go. How set in stone is that 2-3 years rule?

From a disease perspective, cervical cancer's temporal trajectory can appear counterintuitive, moving slowly in long-term monitoring of pre-cancerous cells or moving rapidly in patients suffering metastasised cancer.

Socially promulgated, female sexual-behaviour norms shift across temporally framed periods drawn from the child-maiden-mother-crone progression. From this social norm perspective, women are viewed in term of their pre/post sexual activity, childbearing potential, middle age and post-sexual activity.

could the injection leave me infertile? or if i wanted to get pregnant in about 4 years time would it harm the baby in any way?

Finally, women's private, personal views of themselves shift in relationship to life experience, among other factors. For example, the sexually transmitted disease aspect of cervical cancer may loom larger at 15 than at 50.

The intensity continuum

The term intensity is used here as a characteristic of a question's emotional weight and/or immediacy. Low intensity posts include casual language even when they concern high-risk situations. High intensity posts incorporate affect, often as a motivation for asking.

I've heard its three needles in the arm. Its not the needles Im scared of, its the pain. :( So is it painful and how painful?

I am 17 and suspect that I do have HPV, though my last pap in July was normal - I have to go back next year to check if there's any abnormal cells. What are the chances of HPV turning into cervical cancer over time? Please help!

I have never got a pap smear in my life. I just turned 20 in july. I'm too scared to get one now because I'm afraid I will have hpv and of cervical cancer.

(Many posts included hpv which is the common abbreviation for "human papilloma virus".)

These three posts include statements of emotion (scared and afraid) as well as the emotion's instigator (needle pain, cervical cancer in follow-up pap and cervical cancer/human papilloma virus in a delayed Pap smear). Although no coding technique can determine the intensity of any particular emotion in relationship to any specific emotional instigator, posters obviously vary in their willingness to express their own intensity perceptions.

The sexual behaviour continuum

Within a wide social context, the physical and emotional intimacy of sexual behaviour might encourage the use of these anonymous social question-and-answer sites by questioners interested in the intersections between cervical cancer and their own sexual activities.

…my last [of the three shot series] is in three months and honestly I don't want to wait that long. I have a boyfriend and I would really love to lose my virginity to him soon. I mean if we use a condom that should be fine won't it?

On a clinical level, the connection between sexually transmitted diseases and cervical cancer is clear, but the permutations of sexually transmitted disease transfers vary sufficiently to raise questions about specific activities among laypeople.

If one is a lesbian would the cervical cancer jab still be useful? I am aware STDs and STIs can be passed through girl-girl sexual contact by the way

A friend told me that when many sperms (even healthy) of different men gets injected in a single vagina (not necessarily at a time) then it raises chances for some STDs. This happens when a girl is in a habit of having sex with different men in shorter interval of days & doesn't clean her inner vagina properly after sex or before next intercourse with diff. partner.Sometimes even properly cleaning doesn't help at all.Is this somewhat true?

Personal agency continuum

Personal agency refers to awareness of the nature of an individual's control over a specific situation or life context (MacMurry, 1957; Vallacher and Wegner, 1989). The agency that girls and women bring to the problem of cervical cancer has several aspects:

- legal, e.g., minors required to take the vaccine;

- social, e.g., timing and circumstances under which to become sexually active;

- medical, e.g., frequency of screening tests;

- affective, e.g., emotional perspective on the relationship between self-worth and sexually transmitted diseases.

In the cervical cancer context, agency generally shifts across individuals' life stages from pre-pubescent through end-of-life. The agency continuum is, therefore, the most complex of the four.

Cervical cancer considerations begin with the vaccine, when girls are minors and, in some cases, already sexually active. The girls' personal agency in this first stage would seem to be severely limited but several posts indicated an interest in controlling their sexual history narrative.

Do nurses inquire about how sexually active your are before giving you the jab against cervical cancer either at school or the doctors?

Do docters ask the parent to leave when they are asking the child about sex?

When sexual activity begins to play a larger role in their lives, their sense of control over the cancer increases as well.

Is the only way you can get cervical cancer is by having sex? I'm 16 and I don't want the cervical cancer jab [84]because I'm only having sex when I'm married. I'm not the kind of person that 'gives into temptation in the heat of the moment' and I've said no many times before. But my mum really wants me to get it. Help?

Is it possible when a totally healthy girl having more than 10 male sex partners (all healthy) has a chance of getting infected just because she has so many sex partners no matter if all are healthy?

A human papilloma virus diagnosis becomes one more point of sexually-related inevitability for some; other questioners' agency, however, strengthened as they recognised their ability to actually prevent the cancer.

I have hpv an i'm only 14. What are the things i can do to stop it before i get the cervical cancer?

Finally, the vaccines are also available for men in terms of reducing human papilloma virus as a precursor to throat and anal cancers and as a means to avoid passing the human papilloma virus to girls and women. As is common with birth control (Fennell, 2011), however, the vast majority of cervical cancer education puts all responsibility for human papilloma virus prevention on women. A few posts addressed or acknowledged that pattern.

since most girls catch HPV from a guy, wouldn't it reduce the number of girls who have it if we reduced the number of guys who have it? Does anybody have any idea why it's only for girls?

Given women's potential control over cervical cancer, through vaccines and screening, the agency continuum lies at the heart of a healthier life. Of course, screenings identify but do not prevent active cancer. Acting on early detection notification does significantly increase successful treatment. Including vaccines and screenings as part of sexual wellbeing requires women's personal agency to, at the very least, complete uncomfortable and highly intimate procedures on a life-long basis.

Discussion

Our findings concerning three research questions (the subject of information requested, the types of answers solicited and the information provided to contextualise the requests) provide insight into the cervical cancer-related queries in the social question-and-answer environment. The primary subjects were causes and prevention of cervical cancer; clinical questions, (including symptoms, diagnosis, prognosis and treatment) were less commonly posted. A contextual factor to be noted is the relatively recent release of two vaccines with significant ability to limit cervical cancer. The commercial, school and medical promotion of the vaccines makes prevention more realistic and causes a more immediate information need than the much less common situations of cervical cancer as a disease (e.g., treatment, prognosis). Undoubtedly, the Yahoo! question-and-answer platform's structure as a general social question-and-answer service encourages more immediate (e.g., the vaccine) than on-going (e.g., chemotherapy) concerns. An established discussion forum on women's health would garner more posts on the latter (Noh et al., 2009), providing a valuable contrast between the two formats.

Consistent with prior studies on social question-and-answer questions (Zhang, 2013; Westbrook, 2015), the requested information types included fact, explanation, advice, personal stories and emotional support. In this work, the majority of the questions asked for simple or binary factual answers; a small portion sought elaborate explanations, advice or personal stories. Many requests for simple factual answers appeared to seek validation of anecdotes or myths that had emerged from social conversations.

Does genital warts lead to high risk cervical cancer. I'm hearing yes and no which is the truth?

Just as some social connections fail to provide clean answers, so too do the more static Web sites fail to provide sufficiently specific data.

i look everywhere online and they just show percentage of survival. Obviously my my mom isn't going to survive. I want to know how long she has at most.

Perhaps distilling complex situations to simple binary or factual posts assists questioners determine their absolute priority. Other information seeking patterns, such as the monitoring/blunting style (Case, Andrews, Johnson and Allard, 2005), foreground the affective nature of cancer situations. People with blunting style would choose to offset the impact of distressing information by limiting the amount of information sought (Miller and Mangan, 1983). Seeking binary and factual answers in a single-contact forum (e.g., a social question-and-answer site) gives questioners great control over the nature and amount of information they receive. Certainly other studies' use of in-depth interviews and focus groups would reveal more of the why between these deceptively simple queries.

This current study extends earlier work (e.g., Zhang 2010) by identifying supporting information posters include in their questions. Examples, justifications (suggesting their own beliefs and knowledge), medical histories and emotional states personalise their requests. Additional research can illuminate these information need post augmentations. Such work would have significant implications for defining relevance in the social media environment (Kim and Oh, 2009).

This current study also contributes to a better understanding of the characteristics of users' information needs related to cervical cancer. It suggests that posters construct their information needs concerning cervical cancer along four dimensions: time, intensity, sexual behaviour and personal agency. The time dimension is both biological and social. The former refers to the fact that users' concerns can take place at any time during their lifetime or any stage of the disease. The latter indicates that users' concern can take place at any stage of their social life, such as child-maiden-mother-crone. The intersections of these biological and social temporal frames shape individuals' relevance criteria (Kim and Oh, 2009). To take but one example, questioning Gardisil's immediate side effects (a specific point in the disease life cycle) requires different answers to a pre-pubescent girl and that girl's mother.

he intensity dimension refers to the concentration of emotions involved in the questions. Merely identifying this continuum is problematic in that intensity cannot be reliably deduced from reading a single message. Choosing to share an indication of intensity does not mean that a poster is more concerned than one who does not choose to do so. On the grounds that many questioners made explicit efforts to express the intensity of their need, this continuum merits a provisional discussion.

The sexual behaviour dimension reflects the fact that many users perceived strong relationships between their personal sexual choices and the human papilloma virus and, by extension, cervical cancer. This conceptualization indicates that cervical cancer should certainly be part of sexual health decisions. Both prevention efforts and contextualised sexual behaviour significantly affect a woman's chances getting cervical cancer. This conceptualization also calls for respect for individuals' personal choices with no outside expectations of normative female sexual lives.

The personal agency dimension refers to awareness of an individual's control over a specific situation or life context (MacMurry, 1957; Vallacher and Wegner, 1989). Given women's potential control over cervical cancer through vaccines and screening, this agency dimension lies at the heart of a healthier life. Including vaccines and screenings as part of sexual wellbeing requires women to maintain sufficient personal agency to, at the very least, make private health decisions on a life-long basis.

Conclusion

Social question-and-answer sites provide a high degree of anonymity and the likelihood of a rapid response, both qualities valued by women facing personal questions on cervical cancer. This study of 200 cervical cancer-related posts from Yahoo! Answers suggests that women in this context:

- have a high demand for cause and prevention-related information;

- want simple or binary answers to clarify information received from social conversations or to guide decisions on sexual behaviour;

- expect to receive highly personalised from social question-and-answer sites;

- have information needs characterised by (a) life or disease stage, (b) emotional intensity; (c) personal and social sexual behaviour norms; and (d) cervical cancer agency.

This study begins to suggest practical implications for print, Websites and interactive educational materials, as well as for intervention programmes, on cervical cancer. Extended direct work with girls and women would, for example, examine the most effective means of providing the cause-and-prevention data most commonly requested. Perhaps, in addition to providing clinical materials about cervical cancer, further educating the general public would prove effective. Users' heavy demand for factual information evokes the potential to study the means by which productive information could be presented at both factual and explanatory levels. The four characteristics of the information needs further provide a set of decision-making lenses that can be used to customise, or allow questioners to customise, their information seeking. For example, simply ranking the four continua for any single question (e.g., is intensity more critical than time?) indicates preferences among answers (e.g., intensity calls on unambiguous, direct answers while temporal drivers call on material that pertains only to a single life-stage, such as puberty).

Building personally responsive, robust information infrastructures for these critical care situations requires research rooted in the affective and cognitive aspects of information engagement within and beyond social media forums. Of the numerous opportunities for extending this study, we urge the following two, in addition to those mentioned above. The first is analysis of gynaecological information quality and accuracy (see Genuis, 2012; Oh and Worrall, 2013), with particular attention to the medical-social power dynamics of reproductive rights (see Burke, Coles and Di Meglio, 2014; Stidham-Hall, Moreau and Trussell, 2012). For example, do information quality standards and characteristics shift in relationship to socially normed sexual behaviour? The second area is the bird's eye view of multi-modal active information seeking on high-risk gynaecological concerns, including cognitive (see Vechtomova, 2009), affective (see Nahl and Bilal, 2007) and behavioural (see Wilson, 1999) frameworks. For example, are women who are behaviourally comfortable with social media more likely to take their factual questions to question-and-answer forums rather than their gynaecologist? In better understanding this relatively straightforward women's cancer, Information Studies scholars work from an information baseline on extended questions with somewhat enhanced efficacy.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Jin Gao for her assistance with data collection and part of the data analysis and Zixiao Wang for his assistance with data collection.

About the authors

Lynn Westbrook is an Associate Professor at the University of Texas School of Information with an MLS from the University of Chicago and a PhD from the University of Michigan. Her research interests focus on the cognitive and interpersonal aspects of human-information interactions with emphases on women in crisis situations, particularly intimate partner violence, gynecological cancers and sexual human trafficking. She can be contacted at

lynnwest@ischool.utexas.edu.

Yan Zhang is an assistant professor in the School of Information at the University of Texas at Austin. She received her PhD from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her current research interests focus on information behaviour with emphases on consumer health information search behaviour and consumer health information system design. She can be contacted at yanz@ischool.utexas.edu.