Using empirical data to refine a model for information literacy instruction for elementary school students

Valerie Nesset

State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA

Introduction

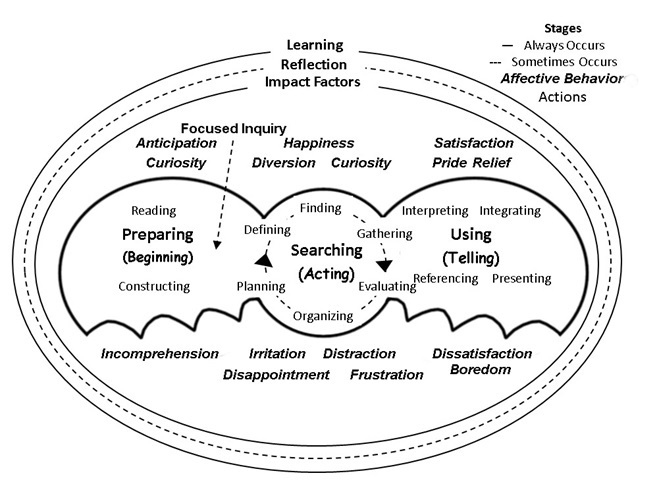

Empirical research in 2006 with two third-grade classes in a Canadian public elementary school led to creation of a model of children's information-seeking behaviour (Nesset, 2009). Subsequent examination of prior research in information behaviour revealed that few, if any, models that have been developed using empirical evidence from studies of young people (e.g., Agosto, 2002; Kuhlthau, 1988, 1991, 2004; Shenton, and Dixon, 2003; Shenton, and Hay-Gibson, 2011) have been based on research with students in the early grades of elementary school. Furthermore, while these models begin to address the research process more holistically, they still tend to focus heavily on the search task. Since the findings of the 2006 study indicated that younger students, before they can begin searching for and using information may require much more preparation in terms of instruction than older students, the data from the study were re-examined through the lens of information literacy instruction (e.g., Bruce, 2000a, 2000b; Herring, 1996, 2009; Wray, and Lewis, 1995), leading to revisions to the model which included adding concepts reported in the information-seeking behaviour literature (e.g., Kuhlthau, 1991, 1993). As a result, two versions of the original model were developed: the rather complex preparing, searching, using model, designed to inform educators, and the simplified beginning, acting, telling model, designed to present to children (Figure 1) (Nesset 2013).

Method: the second, pilot study

In spring 2012 a pilot study using a similar methodology to that used in 2006 in Montreal, Quebec (Nesset, 2009) was conducted in two third-grade classes in a public elementary school in Buffalo, New York. The original purpose of this study was to determine if and how the presentation of a visual of the beginning, acting, telling model (using the full preparing, searching, using model to inform the lessons) could help the students to identify, internalize, and assimilate the information literacy skills necessary to conduct successful research; there were no plans to further revise the model.

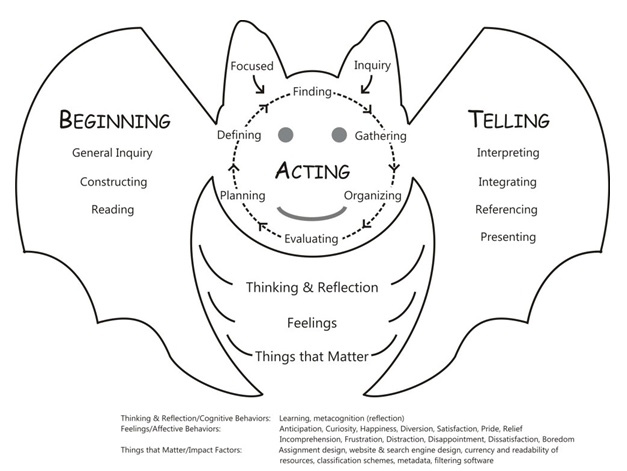

A phenomenological, qualitative methodology was used, including interviews, participant observation, and surveys and questionnaires. Several posters of the simplified beginning, acting, telling model (Figure 2) were placed in the classroom to be used as visual aids. The researcher acted as a co-educator (participant observation), starting each class instructing the children on how to use the beginning, acting, telling model to help them with all aspects of the work required to successfully complete their projects. Each class had a different project: in one class students examined biospheres while in the other, countries of the world. While each individual student was required to submit a completed project, the students often worked together in groups, as they had to share resources. A research assistant observed the classes and made extensive field notes and the classroom sessions were audiotaped. Pre- and post-questionnaires were distributed to the students to determine any changes in behaviour and/or perceptions of the research process before it began and after it ended. Throughout the study, informal, semi-structured interviews were conducted with the teacher who acted as the main instructor for the two classes and of the two individual classroom teachers. Any non-textual data was transcribed. Analysis of the data consisted of coding for major themes and patterns according to practices outlined in Lincoln and Guba (1985) and Patton (2002).

Results

Study results demonstrated that with its engaging mnemonic and visual depiction of a stylized bat, the beginning, acting, telling model did help most of the students to successfully navigate the basics of the research process. As one student stated, 'I went back to Mr. Bat when I forgot to write down [necessary information]'. Another student mused, 'When I thought I was done I looked at the Bat and I [realized that I] was not done'. Further analysis of the observational data, however, indicated that the model was likely effective because the teacher often verbally provided more information about the actions and other concepts associated with each stage. As research into intellectual development (e.g., Piaget and Inhelder, 1969) indicates that children of this age think in more concrete terms, it would follow that these verbal instructions and explanations may not have been as easily assimilated or remembered as would a visual depiction. This important finding suggested the need for a more robust visual representation, something that was less complex and textual than the original preparing, searching, using model to better appeal to younger students, but that would still provide in one visual all pertinent aspects of the research process.

Discussion: the revised beginning, acting, telling model

The findings indicated that the two versions of the model, one for informing instruction and the other for presentation while useful, could be an even better teaching and learning tool if integrated into one. As the preparing, searching, using model was rather complex and did not make effective use of imagery and mnemonic, it was decided to integrate its most important, more abstract concepts such as metacognition, affect, and impact factors into the beginning, acting, telling model (Figure 3).

While all of the main features from the preparing, searching, using model were integrated into a stylized image of a bat in motion, some of the more sophisticated and/or complicated concepts were translated into child-friendly language. For the benefit of educators, the more pedagogically correct terms along with their associated sub-concepts (e.g., affective behaviour and impact factors) were included in textual form below the image. As with the original preparing, searching, using model, the revised model consists of three fluid stages. In the highly instructional beginning stage, so named as it is the start of the entire research process, the teacher introduces the topic of study at its broadest using activities related to the two main concepts, reading (e.g., vocabulary exercises, reading aloud and/or silently) and construction (e.g., concept mapping) to prepare the students to work on their own in the following two stages. The second stage, acting, is prefaced by the 'focused inquiry', similar to Gross' (1995, 2000) 'imposed query' and Kuhlthau's (1991, 2004) task initiation stage. The focused inquiry, assigned by the educator, is typically an explicitly worded, narrower aspect of the broad topic introduced towards the end of the beginning stage. In the acting stage, so named because students begin to act on their own, taking charge of their own behaviours and learning as they actively engage in the research process, activities centre on the six main actions: planning, defining, finding, gathering, evaluating, and organizing. The third and final stage, telling, is more cognitive as the students, with help in the form of direct intervention by the educator if necessary, strive to interpret the information they have found in the acting stage, integrate it into a form that satisfies the assignment requirements, reference their work, and then present it. As the research process is an iterative one, metacognition is encouraged and made explicit by the term "reflection" included in the image.

The model also makes use of representation to provide additional depth and meaning. The first and last stages, beginning and telling, depicted as the bat's wings, its supporting structure, are meant to represent the role instruction plays in the process, whether corporate, where the educator instructs the entire class, characteristic of the beginning stage, or individual, where the educator directly intervenes to instruct a student, characteristic of the telling stage. The acting stage, as the head of the bat, signifies the individual and take-charge nature of the search process, with the focused inquiry incorporated into the bat's ears, which in the real world act as the bat's guide. Finally, the more abstract concepts integral to the entire process, such as metacognition, affect, and impact factors, are explicitly presented in child-friendly language (Thinking & Reflection, Feelings, and Things that Matter) within the implied motion of the bat's wings, representing things that can affect the bat's flight.

Conclusion

While the original purpose of the second study, that is to test and validate the efficacy of the two representations of the model was not realized, the study was successful in its informing of a more holistic iteration of the model. The final beginning, acting, telling model uses a familiar and intriguing image and mnemonic to promote recognition and facilitate memory of information literacy concepts to empower these young students to become self-learners.

Further research

Now that the final iteration of the beginning, acting, telling model has been completed, the plan is to conduct a larger validation study involving elementary school librarians in collaboration with classroom teachers in all the elementary schools within a Western New York school district. To help accomplish this, in addition to copies of visual depictions of the model, appropriate curriculum support such as lesson plans and training modules will be designed and created.