Expected and materialised information source use by municipal officials: intertwining with task complexity

Miamaria Saastamoinen and Sanna Kumpulainen

School of Information Sciences, University of Tampere, Finland

Introduction

People often need to seek for information in various information sources to perform both work and leisure time related tasks. Information seeking is an integral part of tasks and, therefore, task traits direct information seeking. Thus tasks and information seeking intertwine and should be studied in tandem in order to understand tasks’ effects on information activities.

Empirical information seeking studies have a long history in which information needs and uses in different environments are analysed. The literature contains several theoretical information seeking models, such as those of Paisley (1968), Allen (1969), Dervin (1983) and Kuhlthau (1991). Paisley discusses different social groups and institutions that affect a person's information seeking behaviour to various degrees. He arranges the factors into a system of concentric spheres. The factor that affects the most is at the centre; that is the information seeker's personality. Allen revises Paisley's model by stating that the effects of social groups, or their strength, on information seeking behaviour are not static. Dervin suggests in her sense-making approach that information seeking is gap-bridging after encountering a problematic situation. Kuhlthau presents six phases of the information seeking process; each phase involves characteristic thoughts, feelings and actions.

It is less common to analyse tasks as variables in an information seeking study. The task aspect may be ignored (Ibrahim, 2004; Taylor, 1968) or, more generally, the whole study is focused on information seeking in one task type, such as everyday problem solving (Savolainen, 2008), searching for health information (Harris, Wathen and Fear, 2006) or the process of writing a dissertation (Kallehauge, 2010). Even Kuhlthau’s classic model of information search process was originally based on information seeking of students writing a term paper (Kuhlthau, 1991). Task classifications in several studies concentrate on only a few specific task types that are difficult to generalise to other environments (for example Du, Liu, Zhu and Chen, 2013; Serola, 2006; Kwasitsu, 2004). Task complexity is a task feature that can be conceptualised to support generalisation. The concept of task complexity is discussed by, for example, Li and Belkin (2008), Campbell (1988) and Vakkari (2003). It has also gained attention in some empirical studies: Byström and Järvelin (1995) and Byström (2002) found that task complexity was clearly connected to information source use. Hansen (2011) connects task complexity to different task types. Kumpulainen and Järvelin (2010) and Saastamoinen, Kumpulainen and Järvelin (2012) discuss task complexity based on empirical research. We still need more information about how tasks affect information seeking because the fact that information seeking happens only for a reason and in a meaningful context, should not and cannot be ignored. Understanding the real work context, where the sources are used, is a key factor in understanding information behaviour and further developing more appropriate information systems.

In this study, we analyse the use of information sources in the context of varying task complexity and from the perspective of task performers. Participants were asked to estimate task complexity with several variables and report the sources they were planning to use and the ones they finally used. The participants were allowed to name the sources freely, and the researchers formed a suitable source categorisation afterwards.

The present study uses Byström's (1999, 2002) work both theoretically and methodically. We also share a common organizational setting. Therefore we discuss Byström's study throughout the paper, and in the discussion section our findings are compared to hers. Moreover, the temporal difference enabled a comparison of current city administration with that of the mid 1990s when Byström's data was collected.

The findings in our two earlier papers (Saastamoinen et al., 2012; Saastamoinen, Kumpulainen, Vakkari and Järvelin, 2013) are based on the same research project and data set. However, they all have distinct contributions that do not fit in a single paper. The first paper (Saastamoinen et al., 2012) discussed the findings based on observation data; information source use, information retrieval and problems the researcher observed while the participants performed their work tasks. The second paper (Saastamoinen et al., 2013) studied the expected and materialised information types (information aggregates, facts, known items) based on questionnaire data. The present paper concerns the questionnaire data, as well, but the focus is on the information sources (human sources, organizational information systems, the Web, e-mail, other sources) the participants used. Different literature and theory are discussed in the two papers, respectively. Presenting all findings of the research project and the versatile data set in one paper would have been impossible both in terms of length and readability.

The specific research questions for this study are:

- Which information sources are expected to be used at task initiation and which information sources are dropped during the task process?

- Which expected information source uses are materialised and which information sources are discovered only during the task process, that is new, unexpected sources?

- How does task complexity affect the expected, dropped, materialised and new information sources?

- Which information types are sought for in different information sources?

The research questions are answered by analysing questionnaire responses concerning fifty-nine tasks of city administration professionals. We take a quantitative approach to the analysis, and shed light on information source use in real-world tasks of varying complexity.

Literature review

A task is a sequence or a group of activities that are performed in order to attain a goal, that is an outcome (Vakkari, 2003). Task traits affect the information seeking process (Leckie , Pettigrew and Sylvain, 1996), and especially task complexity is an important factor (Byström, 2002). Though acknowledged and discussed as a task feature, task complexity does not have a common definition among researchers. (See Saastamoinen et al., 2013 for a more thorough discussion about tasks and task complexity).

Information sources are the means of information seeking, and the bridge between information needs and information use. The theoretical concepts of information needs, seeking and use have been widely discussed in information studies literature (e.g. Case, 2006; Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005), whereas the more concrete concept of information sources has often been regarded as a simple truism. We argue that information sources are theoretically interesting instruments of the information seeking process. In many studies, the theoretical reasoning behind the source types chosen has been neglected although the types reflect the study itself on a meta level (if the data are fitted into a ready-made source classification) and perhaps more importantly the phenomena studied (if the classification is based on the data). Thus the information sources missing from the data are as important as the ones observed, for instance. Common grounds for information source analysis would facilitate comparing studies and hence accumulating knowledge in information science. However, this does not indicate that we should invent a single, all-purpose source classification. Instead, we should introduce and become conscious of the features of the sources and the classifications in order to compare the use of sources sharing similar features across studies. Next, we will propose some useful concepts for analysing information sources. We also give some examples of the use of these concepts in the literature.

Figure 1 distils the contexts that may indirectly affect the selection of features in classification of information sources. Time, place and aims of the research are inevitably defined before the source classification, and the classification is either data- or theory-driven.

Every research project is bound to its physical (temporal and spatial) context. A classification can hardly describe nor needs to describe the sources that have not yet been invented or are used little because of their novelty or antiquity. For example, Web sources and electronic data systems are considered to be more important in city administration contexts today (Saastamoinen et al., 2012) than they were in the mid-1990s (Byström, 2002). The same goes for other contexts, too, such as libraries (Taylor, 1968 versus Ibrahim, 2004). The spatial context of research may be a country or a more specific place such as a rural area (e.g., Harris et al., 2006), which may pose preconditions to the source classification. The place may still affect the classification, even if the spatial context is not an explicit variable in the study (which often is the case).

In addition to the physical context, research goals and questions in each study guide the ways how to construct the source classifications. For instance, work related information seeking studies include special sources needed in the named work context, such as the Web of Science and Google Scholar in the case of researchers (Nicholas, Williams, Rowlands and Jamali, 2010) and bio-databases in the context of molecular medicine (Kumpulainen and Järvelin, 2010). Everyday life information seeking studies are more likely to reveal generic, leisure time related sources such as friends and newspapers (Harris et al., 2006; Savolainen, 2008). Work and everyday related classifications may be partly congruent at the surface level, as well. For example Babalhavaeji and Farhadpoor (2013) study library managers’ environmental scanning, and in that context newspapers and broadcast media are relevant information sources for the participants. Thus the studied tasks (writing a paper, environmental scanning, treating one’s own illness), whether work related or not, define the set of relevant sources. Task types may be a variable in a study (e.g., Du et al., 2013), or they can be implicit whereupon the varying tasks are reduced to one task type, such as problem solving (e.g., Kallehauge, 2010).

Source classifications are either (mainly) data- or theory-driven. By data-driven we mean that the classification stems from the data contrary to theory-driven classifications that are ready-made before the data is analysed or even collected. Theory-driven classifications are naturally applied in questionnaire studies where the use of specific sources is under research (e.g., Morrison, 1993). Data-driven classifications are used in studies that focus first on the participants or the context of information seeking and only then try to analyse the sources used based on grounded theory type of methodology (e.g., Hansen, 2011). Seemingly, the basis of source classification may change from data-driven to theory-driven or vice versa during the research process. The researcher may begin to analyse the data to find meaningful classes and only then realise that a ready-made classification suits perfectly; or the classes used in a questionnaire prove useless and must be rearranged.

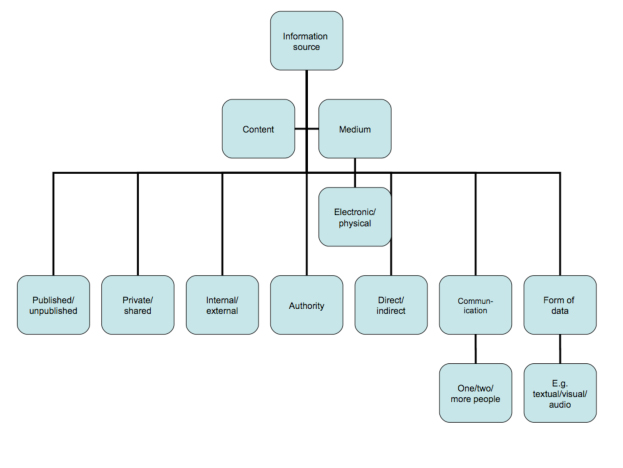

The information sources themselves are characterised by eight facets that describe them (see Figure 2). The facets are:

- content vs. medium;

- published vs. unpublished;

- private vs. shared;

- internal vs. external;

- authority;

- direct vs. indirect;

- communication; and

- form of data.

All of these facets may not be applied to all sources at the same time but various studies and categorisations emphasise them differently. Firstly, all information sources are labelled by either the contents or the medium (1) of the information object. This is an inevitable feature of all sources. Contents are a type of information objects that are named without binding them to a medium but that are still regarded as sources, not information types in a classification. For example Hansen’s (2011) classification has some sources of type medium, e.g., Web sites and online articles. In the empirical domain of his research, patent engineering, Hansen also has content based source classes, such as bibliographic information and classification code schemata.

If a source is of type medium, it must either be electronic or physical. This feature is not applicable to content labelled sources because bringing the aspect to a content actually makes it a combination of both the content and the medium (for example electronic minutes). The classification of Chowdhury, Gibb and Landoni (2011) exploits the medium perspective: they itemise only electronic sources (called digital), e.g., e-journals and e-books. One possible medium type is physical sources including all kinds of papers (Saastamoinen et al., 2012) and printed sources (Savolainen, 2008).

Secondly, published and unpublished (2) sources can be separated. This feature is related to the third facet, private and shared (3) sources. Books are published sources but they may be part of private collections. Private (personal) collections are separated from other sources for example in the classifications of Chowdhury et al. (2011), Kwasitsu (2004), and Taylor (1968). One’s own observations or memory are also private sources as distinguished by, for example, Kwasitsu (2004), Taylor (1968), and Morrison (1993). Shared sources are the opposite of private sources meaning that they are potentially shared with other people and not privately saved on one’s own personal computer, for example.

Many classifications discriminate internal and external (4) sources, resembling the separation between private and shared sources in a larger scale, often regarding an organization. However, there is not just one correct use of the concepts of internal and external; they must be defined again in each study. Naturally, external sources are notably different from internal ones though their boundaries may differ across studies. Internality may also involve all sources, only some of them, or the internality can be judged afterwards based on implicit assumptions though not considered in the initial classification. Du et al. (2013) separate internal and external sources, as well as Kwasitsu (2004) and Babalhavaeji and Farhadpoor (2013). However, unlike Byström (2002), they have different sources in external and internal classes. Byström’s classification is on a more abstract level and thus all her sources, with the exception of visits and registers, have internal and external counterparts (e.g., people concerned in the matter at hand and literature). She judges internality by the location of the source. There are two alternatives, inside or outside the organization. Another perspective to internality is the place of production of the information content of the source (Saastamoinen et al., 2013).

The fifth facet concerns the authority (5) of a source. This aspect is seldom explicitly stated in source classification but in a research setting some sources are often more authoritative than others. This may concern the legal status of a source or other social ways of justifying the use of a source. For example Guo (2011) specifies several implicitly legitimate sources of information in the context of new product development including suppliers and collaborating organizations. Guo’s classification of the sources is pre-made for a questionnaire. Because of the field Guo studied, it is understandable that his classification automatically excludes unauthoritative sources such as a doctor or friends. On the other hand, a doctor may be a self-evidently important and legitimate source in a different context, that is, when searching for health information (e.g., Harris et al., 2006).

Sources have been defined as carriers of information content (Ingwersen and Järvelin, 2005; Byström, 2002). Case (2007) however argues that this application of the term source is actually incorrect. According to him, a source is the primary producer of information, for example the author of a book and the book should be called a channel. A channel may be understood as a broader concept, as well as a medium giving access to sources (Boyd, 2004; Byström, 2002; Serola, 2006). For example libraries, reference books or people can act as channels in this respect. As the relationship of these two concepts is somewhat complicated and equivocal, we only apply the term source for simplicity. The source or channel question may be the sixth facet, which will be called here direct and indirect (6) sources. Direct sources, such as printed journals in Jamali and Nicholas’ classification (2010), provide the information needed directly. Of course arguments may be made against this perspective, depending on the use of the source in question. A printed journal may be browsed in order to attain new references. Jamali and Nicholas have a separate class for reference lists so a journal is obviously a direct source in their study: searching Google is one option to identify relevant articles in their questionnaire. Google may be regarded as a direct source if the information needed is already present in the snippets of the result list; that is if the list in itself satisfies the information need. In many cases, a search engine is unlikely to provide the information right away, providing as it does a list of links to potentially useful Web pages in response to a search. In this sense, Google may rather be described as an indirect source in terms of our classification. Xie and Joo (2012), Kumpulainen and Järvelin (2010) and Chowdhury et al. (2011), among others, separate search engines and single Web pages in their classifications which reveals the underlying aspect of directness.

Communication (7) between people is regarded as a special way of seeking information in many studies and thus it is our seventh facet. If communication is recognised as a source in a classification, it may be done by emphasising the contents of the communication or communication tools. This returns to our first facet common to all sources, the separation between contents and medium. However, contents in the context of communication may be interpreted as the people to be communicated with (friends, a doctor) compared to media (e-mail, mail, telephone, etc.). Many classifications also recognise meetings and/or institutions as sources alongside individual people. Guo’s (2011) classification of sources in product development is oriented toward organization and people, having categories such as competitors and university. Koo, Wati and Jung (2011) study the use of communication technologies and accordingly their information sources are communication tools: blogs, e-mail, telephone, video conferencing and instant messenger. Wilson (1981) makes a classic grouping of information sources to formal information systems in a broader sense than only on-line services, other information sources and other people. This grouping stresses the importance of human sources and the role of, as Wilson calls it, the information exchange that happens between people. A similar division is made by Hansen (2011) between paper, electronic and human source types.

The last source facet concerns the form of data the source provides (8). The data may be for example textual, visual, audio, raw data or programming code (or any combination), sometimes also confusingly called media or content. The division between forms of data is seldom explicit in source classifications but it still exists. Textual data may be assumed as a default when a category such as the Web is formed. However, communication is often a natural application of audio data, and talking to a person may differ from, for example, sending e-mail, in that one can express oneself and react quickly. Therefore some classifications break the communication category down to the level where face-to-face interaction can be identified (e.g., Saastamoinen et al., 2012). Source classifications in general do not analyse, for example, whether a book is used to attain text or images; perhaps because a picture is more often considered as an information type than as a source. However, an opposite view can be fruitful. For example Hansen (2011) found that images played an important role as a source in patent professionals’ information seeking. Furthermore, Serola (2006) discovered a source type of direct observation where city planners went to actually see the place they were intending to plan. They photographed the scene to make the information tangible, which seems to parallel the function that images of inventions have for patent professionals. Both far-reaching planning of city areas and deciding for patents need tangible, visual information. This point of view differs from what Lloyd (2006, 2010) refers to as physical or corporeal information.

Corporeal information is gained through acting in a situation (such as fire fighters in the case of extinguishing a fire) and watching others acting. Thus, this intangible and often implicit information is the opposite of Lloyd's textual information because the former cannot easily be documented. Lloyd does not make a distinction between text and images, as they are both a type of formal information. It cannot be denied that people do gain a lot of information by acting in the world themselves. However, this action may rather be called learning than an information source in the context of information seeking studies. If defined through more tangible source features, corporeal information means actually using human sources; one’s own self or other people (in our classification direct private communication, probably both visual and audio information). Lloyd has a category for social information as well but it relates to forming a 'shared view of practice' (Lloyd, 2006, p. 575). Moreover, Lloyd uses the concepts information and information source quite interchangeably.

Byström (1999) has an information source category similar to corporeal information, namely visits as sources. However, these visits are rare in her data and they seem more equivalent to photographs: visits are clearly defined inspections to the places in question, not implicit information gaining by doing one's work.

Figure 2, above, distils the features of information sources that were discussed above. The feature of content or medium is the most crucial one in the sense that it is compulsory by definition; one would not have a source at all unless it is either contents or a medium. Combining other features forms divergent information source types presented in information seeking studies. A single source in a classification may be loaded with all of the features or just a few. In general, it may not be possible or appropriate to analyse all of them for all information sources in one study. However, differences and similarities of information sources should not be taken for granted. For example, sample questions might be: Does television differ from newspapers as a source and how? Is a different source being used when talking to a person face-to-face instead of sending an e-mail? What is the added value of printouts compared to electronic records?

The classification features presented in Figure 2 and discussed above are intended as components of a generic classification of information sources. In the present paper, we introduce a data-driven and medium-based information source categorisation that portrays our empirical findings and raises the abstraction level of individual sources. The categorisation is presented in the next section, and the consequences to the interpretation of our findings are reflected in the discussion section.

Study design: participants, methods, and data

The participants were a convenience sample of six administrative employees of a city of some 200 000 inhabitants. All participants worked in the central general administration of the city. They were recruited by an internal agent of the city, and the participation was voluntary. Participants were not offered any compensation for their participation. We had two main data collection methods, namely observation and two task specific questionnaires, one to be filled in at the beginning of each task and the other when finishing it (for detailed questionnaire forms, see Appendices). The results of the observation are discussed in Saastamoinen et al. (2012) while information type use and the features of the studied tasks are more thoroughly presented in Saastamoinen et al. (2013). The present paper covers the results of information source use based on the questionnaires.

The data set consists of fifty-nine tasks consisting of task initiation and task finishing form pairs. In the questionnaires, the participants were asked to list the information sources and information types they were planning to use and the ones that were used. Each task was set a complexity value. Task complexity was defined as the average of five task complexity components, namely 1) task complexity estimated in the beginning and 2) in the end of the task; 3) the task performers’ expertise; 4) their prior knowledge about the task process; and 5) their prior knowledge about the information needed in the task. All of these were estimated by the participants themselves in the questionnaire forms. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the composite measure was 0.79 (confidence interval 0.69-0.87). Task complexity varied between 2 % and 67.4 %. The continuous task complexity was also divided in three complexity categories, simple (20 tasks, complexity ranging from 2 % to 18 %), semi-complex (19 tasks, complexity ranging from 18.75 % to 32 %) and complex (20 tasks, complexity ranging from 33 % to 67.4 %) for most statistical tests and to facilitate the interpretations. In other words, task complexity was used both as a continuous and as a categorised variable.

Our conception of complexity applies Byström's (1999, 2002) ideas of task complexity as the degree of a priori knowledge concerning a task at hand. Similarly, we asked about task complexity directly ('How complex is the task?') in addition to a priori knowledge, and the participants estimated the complexity without any interference of researchers. Thus our task complexity is purely subjective. Because Byström (2002) in her study examined the same city administration that was examined in this study, her methods were used to enable temporal comparisons.

In contrast to the method used here, Kumpulainen and Järvelin (2010) have used a similar task complexity measure. They asked the participants to describe the task so that the researcher was able to estimate the degree of a priori knowledge of the task performer. Their complexity estimate was based on the knowledge the participant could present rather than on the gut feeling of the participant. Thus the complexity measure is reliable as the researcher evaluates all tasks against the same criteria.

Every information source in our data set was classified as human sources, e-mail, the Web, organizational information systems or other sources. These rough classes were reliably identifiable in the data; thus the classification is data-driven. Only the medium, not the content, were taken into account. Similarly, all source types can be used to attain information either directly or indirectly. In principle, organizational information systems are the most authoritative sources. Human sources and e-mail can be regarded as communication channels though they belong to different classes (see below).

For the purposes of this study, human sources is defined as the people and organizations that are mentioned in the forms without a reference to a medium. That is, the participants were not necessarily in contact with them face-to-face but they felt that the person mentioned, not the medium of communication, acted as a source. A few times an organization was mentioned, as well, and these cases fell into this category as no medium was mentioned, and as one can contact only a contact person rather than the organization as a whole. E-mail composes a class of its own because simply naming “e-mail” as an information source was quite common among the participants. All employees in the target organization used the same e-mail client. E-mail was used both as a communicational channel and as an archive for important messages and files.

The difference between the Web and organizational information systems in the classification is that the Web is publicly available on the Internet without a fee, and organizational information systems have restricted access. For example, a Web search engine is part of the class the Web, whereas business management software and internal databases are organizational information systems. In the case of a Web source subject to a charge, it was regarded as an organizational source as it would not have been used without the support of the organization. The last class, other, contains only a few instances that cannot be put elsewhere on good grounds, such as printed books.

Information types were classified as well in order to analyse if sources were used differently with respect to information types. (A more thorough analysis of information types is presented in Saastamoinen et al., 2013.) The classes are facts (e.g., a name), known items (e.g., the record of yesterday’s meeting), and information aggregates (larger themes, e.g., the state of municipal health care). The classes were purely based on questionnaire answers. For example, if a known item was mentioned, we did not guess further whether there might have been a useful fact in the known item. A piece of information was a known item only if it clearly was not either a fact or an information aggregate.

We calculated the expected and materialised source use, and the number of dropped initial and new, unexpected sources. Expected sources are the ones recorded in the task initiation form, materialised sources the ones in the task finishing form. Dropped initial sources were expected to be used but not mentioned in the end; and new, unexpected sources (newcomers) were mentioned in the end but were not expected, respectively. Newcomers and dropped sources required reasoning in their assessment. They do not represent just remainders of expected and materialized sources, as the participants may often express the sources ambiguously. Hence, it was left to the researcher to judge the relationships between the information objects mentioned. In our case, only entirely new or completely abandoned sources were reckoned as unexpected or dropped initial sources.

In addition to the number of sources, the share of sources was calculated. By the share we mean the proportion a source has in a task to be analysed. Naturally, the sum of proportions in a task is one hundred per cent. The proportions of each source were then averaged over tasks in each task complexity category.

Findings

In this section, we present the results on the use of information sources related to task complexity. First, we introduce the main findings concerning each information source; second, we analyse the overall findings concerning expected, dropped initial, materialised and new, unexpected sources. Finally, the relationships between information sources and information types are analysed briefly.

| Organizational information systems | The Web | Human sources | Other | N | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| by % of all sources | expected | -0.27 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.06 | -0.04 | 132 |

| dropped | 0.09 | -0.35 | 0.07 | 0.13 | -0.05 | 29 | |

| materialised | -0.29 | 0.39 | -0.04 | -0.04 | 0.29 | 158 | |

| unexpected | -0.03 | 0.34 | -0.11 | -0.11 | -0.03 | 49 | |

| by source count | expected | -0.24 | -0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | -0.05 | 132 |

| dropped | 0.02 | -0.19 | 0.01 | 0.10 | -0.01 | 29 | |

| materialised | -0.20 | 0.21 | -0.11 | -0.12 | 0.19 | 158 | |

| unexpected | -0.03 | 0.24 | -0.14 | -0.11 | -0.03 | 49 | |

Table 1 presents the correlations between continuous task complexity and information source use. The correlations are quite weak, and only four of them are statistically significant. However, the average proportions of sources are more clearly connected to task complexity than the number of sources; and task complexity is a better indicator of materialised than expected information source use. More detailed findings are presented below.

Organizational information systems. The organizational information systems were the most frequently expected source type in all task complexity categories. The share of information systems reduced with growing task complexity from 62% to under a half. However, the number of times organizational information systems were expected peaked in semi-complex tasks and the difference between semi-complex and complex tasks was statistically significant (Mann-Whitney, p=0.031). All expected use of organizational information systems did not materialise. Organizational information systems had a maximum of 57% share of dropped initial sources in semi-complex tasks. On the other hand, only a fourth of abandoned sources were organizational information systems in simple tasks. In simple tasks, 14% of expected organizational information systems were not used. The share increased a little in semi-complex tasks and to a fourth in complex tasks.

As participants expected, organizational information systems were the most used information source. The share of materialised use of organizational information systems reduced from 59% to a third with increasing task complexity. The difference between simple and complex tasks is statistically significant (Mann-Whitney, p=0.045). In addition, the continuous task complexity correlated with the share of materialised information system use (Pearson’s r=-0.293, p=0.026). Discovering new needs for organizational information systems was not as common as the use itself: 36% of new, unexpected sources in simple tasks were organizational information systems and even less in semi-complex and complex tasks.

Organizational information systems were expected to provide mainly known items (39%) and secondly information aggregates (31%). However, of the information acquired using organizational information systems, nearly a half were of known item type, and only 18% information aggregates.

The Web. Expectations of Web use varied from only 6% (semi-complex tasks) to 19% in complex tasks. Up to a third of dropped initial information sources in simple tasks were Web sources, 7% in semi-complex tasks. However, none of the dropped sources were Web sites in complex tasks. Even over a half of expected Web sources were not used in simple tasks. The share decreased to a fourth in semi-complex tasks and as already mentioned, there were no dropped Web sources in complex tasks.

In simple and semi-complex tasks, the use of the Web had only a small share of materialised source use. Compared to this, the share of the Web became prominent in complex tasks (24% of source use). The share of materialised Web use correlated with continuous task complexity (Pearson’s r=0.389, p=0.003), and the use was significantly greater in complex than in simple tasks (Mann-Whitney, p=0.045) or in semi-complex tasks (Mann-Whitney, p=0.017). Interestingly, the Web and organizational information systems were equally popular in complex tasks (Wilcoxon, p=0.419), though the use of systems was significantly greater otherwise, i.e., in less complex tasks. Additionally, the Web use expectations differed from materialised use in complex tasks both in terms of the share of all information systems (Wilcoxon, p=0.026) and the absolute frequency of use (Wilcoxon, p=0.014): the Web was used significantly more than expected.

The share of new unexpected Web sources among newcomers was about a fourth in complex tasks and it was significantly greater than in semi-complex tasks (Mann-Whitney, p=0.017). The share of new Web sources also correlated with continuous task complexity (Pearson’s r=0.340, p=0.046).

Mainly information aggregates and facts were expected from the Web. The materialised use stressed aggregates more heavily (59%).

Human sources. The share of expected human sources grew with increasing task complexity, being 8% in simple, 11% in semi-complex and 20% in complex tasks. Human sources had quite a large share of dropped initial sources.

Human sources were finally used more than expected, ranging from 18% in simple tasks to 25% in semi-complex tasks, staying at about 20% in complex tasks. The expected number of human sources used was significantly smaller than the materialised use in semi-complex tasks (Wilcoxon, p=0.034) and, in addition, more new human sources were needed than dropped in semi-complex tasks (Wilcoxon, p=0.020). In other words, only one human source out of ten was abandoned whereas almost one new human source was discovered during every other semi-complex task. Indeed, human sources had the largest proportion of new unexpected sources in semi-complex and complex tasks and they shared the largest proportion with information systems in simple tasks.

Human sources were mainly expected when seeking information about larger topics, that is, information aggregates. This also materialised: information aggregates were the main information type sought from human sources (49%), but human sources also provided facts.

E-mail. Expected use of e-mail varied from 14% in simple tasks to 24% in semi-complex tasks. E-mail was seldom abandoned. Only 17% and 13% of dropped initial sources in simple and complex tasks were e-mails and there were no abandoned e-mails at all in semi-complex tasks.

The materialised use of e-mail was astonishingly stable across task complexity categories: the share of e-mail kept around 17%. Only a few new, unexpected needs for e-mail were discovered during task processes and they were independent of task complexity. The share of new e-mail needs varied from 3% in semi-complex tasks to 18% in simple tasks.

Using e-mail was mainly expected when seeking for information aggregates (44%) and known items. The relative strengths of information types changed in materialised use: when e-mail was used, it was most frequently used for finding known items (46%), second most frequently used for finding facts and the least frequently for finding about information aggregates.

Other sources. The use of other sources (mainly of physical or paper type) was infrequent. All expected use of other sources concentrated in the semi-complex tasks (6%) and the materialised use in semi-complex (7%) and complex tasks (6%). The materialised share of other sources correlated with the continuous task complexity variable (Pearson’s r=0.292, p=0.026). Two-thirds of other sources were expected to provide information aggregates and a third of them known items. However, their materialised use concentrates on facts and information aggregates (44% both).

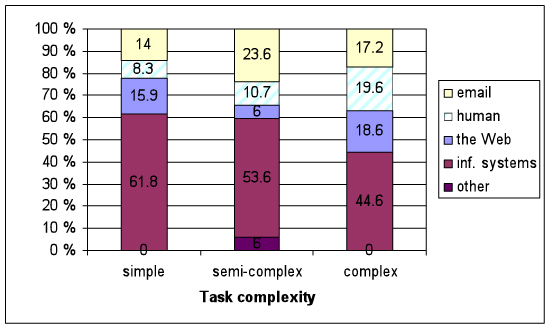

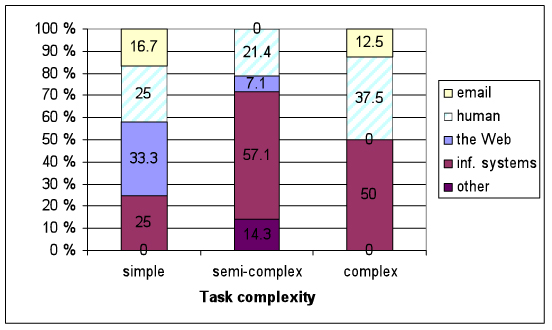

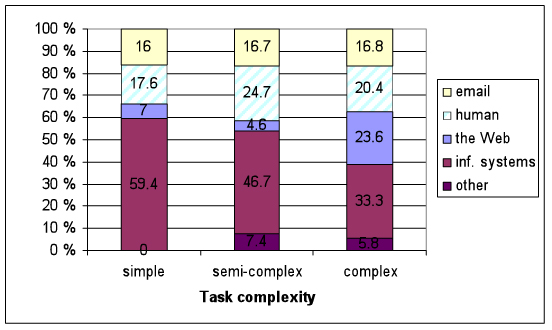

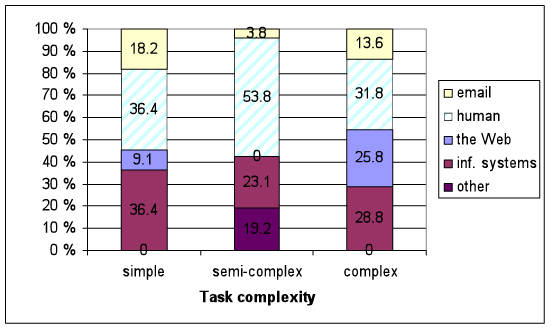

Expected information sources (see Figure 3). Organizational information systems were clearly the most frequently expected information source across task complexity categories though its share decreased with growing task complexity. Human sources were another source that was affected by task complexity: the more complex the task, the larger the share of expected human sources in an average task.

Dropped information sources (see Figure 4). The shares of dropped sources were not rectilinearly affected by task complexity, but for Web sources that had the largest share of dropped sources in simple tasks, a small share in semi-complex tasks and finally, in complex tasks, there were no abandoned Web sources. Apart from simple tasks where the largest group of dropped sources were Web sources, organizational information systems were clearly the most frequently abandoned information source.

Materialised information sources (see Figure 5). Organizational information systems were the most frequently used information source across complexity categories and their share decreased with increasing task complexity as participants expected. However, the total share of materialised organizational information systems was a little smaller than expected. The use of human sources and the Web did not respond to changing task complexity in a linear fashion. In particular, the share of e-mail use was constant despite of task complexity. The sources belonging to the group Other were used little but more often than expected. The data in Figures 3 and 5 are presented in table form in Appendix 4 to enable easier comparison between expected and materialised information sources.

New, unexpected information sources (see Figure 6). The share of new, unexpected Web sources was the only source type where its use correlated with growing continuous task complexity: that is, the more complex task, the more new Web needs were discovered during task process. Overall, human sources had the largest share of new sources regardless of task complexity.

Sources and information types. Information source use was associated with the information types sought for both in terms of expected (Pearson χ2, p=0.021) and materialised use (Pearson χ2 , p=0.000).

| Source | Information type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fact | Known item | Information aggregate | None | Total | N | |

| 8.7% | 34.8% | 43.5% | 13.0% | 100.0% | 23 | |

| Human | 25.0% | 10.0% | 45.0% | 20.0% | 100.0% | 20 |

| The Web | 38.1% | 4.8% | 42.9% | 14.3% | 100.0% | 21 |

| Information systems | 26.2% | 38.5% | 30.8% | 4.6% | 100.0% | 65 |

| Other source | 0.0% | 33.3% | 66.7% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 3 |

| No source mentioned | 26.5% | 20.6% | 52.9% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 34 |

| N | 166 | |||||

Information aggregates were the largest group of expected information types in all information sources with the exception of organizational information systems, which were expected to provide most often known items (Table 2).

| Source | Information type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fact | Known item | Information aggregate | None | Total | N | |

| 32.1% | 46.4% | 21.4% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 28 | |

| Human | 39.4% | 3.0% | 48.5% | 9.1% | 100.0% | 33 |

| The Web | 27.3% | 13.6% | 59.1% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 22 |

| Information systems | 34.8% | 47.0% | 18.2% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 66 |

| Other source | 44.4% | 11.1% | 44.4% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 9 |

| No source mentioned | 44.8% | 0.0% | 55.2% | 0.0% | 100.0% | 29 |

| N | 187 | |||||

In materialised use (Table 3), human sources and the Web were more focused on information aggregates than expected. A larger share than expected was dedicated to searching for known items in organizational information systems, as well. On the other hand, the focus of using e-mail changed from searching for information aggregates to searching for known items and facts. None of the sources were expected to be used nor materialised for searching mainly for facts.

This inspection also included two special categories, namely the ones where the participants either omitted the information source or information type (see Tables 2 and 3). Discussion of that finding is presented below.

Discussion

In this paper, we emphasised both the importance of studying information source use in various real world tasks and also analysing further the meanings the sources and source categorisations carry. Empirical findings from real life accumulate our knowledge better if we are able to analyse sources beyond the ready-made categories that have been formed to support analysis in single studies. To meet these requirements, we will first discuss our own information source categorisation in the light of easily generalisable source features. After this we will discuss the individual empirical findings and their relationships to earlier studies.

The way of categorising information sources

Previous studies influenced the way we categorised and analysed the data. The time and place of a study cannot be ignored. This holds for both physical surroundings and scholarly context. Our information source classification was data-driven in the sense that the participants had a questionnaire with empty boxes in which to fill in the sources they used, not ready categories to be ticked. This approach has the following benefits: it is applicable to many domains, the data can be classified and reclassified easily, the researcher does not have to discover all possible response variants beforehand and the participants can express themselves freely.

The research goals guided the analysis. This is seen in the way that mediums of information, not the contents, are represented in the categorisation: human sources, e-mail, the Web, organizational information systems and other sources. In summary, any of these source types could be used to search for the same piece of information. Our goal with the instrumental source approach was to describe the task effect on information source use. Eventually, this led to some further findings about connections between information sources and information types.

Our information source categories were quite robust as the data set was small, and each category needed to have enough instances to enable indicative statistical testing. Yet a thorough inspection reveals that even these rough categories encompass more subtle features beyond their labels, as well. The features were demonstrated with examples of earlier studies in the literature review of the present paper. Our source categories differ in how many of these features they encompass. Thus following remarks can be made:

- Humans as sources are communicative. The role of human sources was not specified in the categorisation (expert, colleague, etc.). Human sources in our data set represent the facet communication in Figure 2.

- E-mail is a communication tool that often contains unpublished material, usually as text. In principle, it may contain all kinds of data. E-mail in our data set represents mainly the facets unpublished material, communication, and textual data in Figure 2.

- The Web is an external source, and especially a source with all kinds of material (textual, visual, audio, etc.). The material in the Web is published, that is, publicly available. Thus, the Web in our data set represents facets: published material, externality, and different data types as seen in Figure 2.

- Organizational information systems are the internal, restrictedly shared counterpart of the Web that often have high authority (i.e., they are expected to be used in most tasks or the use is even compulsory in some cases). Licensed Web-based software or services were included in the organizational information systems. Organizational information systems in our data set represent the facets of shared and internal information sources with authority facet.

Human sources and the Web are self-explanatory information source types in the sense that their meaning is close to the corresponding layman’s terms. Understanding the role of organizational information systems required more inside information. It was gained both through observational data (Saastamoinen et al., 2012) and the questionnaire responses. Two information source types in particular merit further discussion, namely e-mail and the category Other sources. The latter was so heterogeneous that it could not be labelled in the feature list above.

It was quite surprising how clearly the participants saw e-mail as a source type of its own. They did not just name the people they contacted via e-mail but seemed to feel that e-mail as such is a major resource for working and seeking for information. In observational data from the same tasks (see Saastamoinen et al., 2012), e-mail seemed much used, important and diverse within communicational sources but its intrinsic value crystallised only in consistent questionnaire responses.

Why did e-mail come up so clearly, then? We could argue that the participants named the source type they felt was more important, whether a person or a communicational medium. E-mail may have been used as a source label for example when organizing a complicated issue with several people (the medium uppermost). Alternatively, people are listed by name because they are needed for several purposes (the person uppermost). To separate between these two cases our categorisation considers human and e-mail as separate sources. However, most likely the mere use of the e-mail application was not very helpful in performing the task, whereas the content counts, that is, the information carried by the messages that have originally been sent by people to people. On the other hand, as seen in the observation study (Saastamoinen et al., 2012), the e-mail application was also used as a repository for important attachments and messages. This use of e-mail dissipates the communication function, and actually makes e-mail more like a conventional database. In this sense, habitual boundaries between communicational (human) sources and documentary resources can be questioned. In the case of e-mail, these two perspectives are tightly connected.

Our small category for Other information sources included all printed books and papers the participants had listed in the questionnaire. Other sources were sources that could not be placed elsewhere on good grounds. Though small, the category proved interesting. Because the so-called physical resources were widely used in observational data (see Saastamoinen et al., 2012), it may have implied that this category should have been quite large. This may indicate that though people actually handle plenty of paper documents in their work, they still do not reckon them as sources. Scanning papers may be too habitual to be acknowledged at all. A more probable reason lies in the fact that perhaps little information is found in the scanned papers. This holds for other sources, as well. A source that fails to give the needed information is not a source at all. When studying information seeking behaviour, unsuccessful information seeking is at least as important as the successful one. On the contrary, participants tend to identify a source only when the needed information is found. Of course this does not explain why our participants did not expect that they would use physical sources, either. Perhaps the information should have been found elsewhere but finally they had to turn to paper sources.

Interestingly, observational data revealed that surprisingly many papers were actually printouts even if only files that had been printed during the observation session were counted among printouts (Saastamoinen et al., 2012). A hasty interpretation would be that as a printout contains the same information as an information object in an electronic database, it is an identical and thus an inferior source to the original one. Quite naturally, this is likely to be the participants’ interpretation as well because they were seeking for a piece of information, not a source per se apart from some known items. However, we do not think that printouts are irrelevant sources. Obviously, they were used for a reason, even if only to gratify a habit. Alternatively, reading on a computer screen was sometimes regarded as uncomfortable, and making notes to an agenda easier with pen and paper than in a word processor. Thus, using printouts may relate to usability problems in electronic environments.

Task complexity and information source use

We found indicative results of the effects of task complexity on information source use. Due to the relatively small data set, we were able to detect and analyse further only clearly rectilinear dependencies. We found that task complexity affects the use of

- organizational information systems

- Web sources, and

- human sources.

The use of these three source types is discussed below. We also discuss the possible reasons why e-mail is a relatively important source despite varying task complexity.

First, the more complex the task, the less use of organizational information systems is expected and the less they are used, as well. A natural explanation is that these systems are originally designed to support straightforward tasks so that human resources can be expended on more complicated tasks. It underlines the principle that the processes that are simple and performed often are automated before long to save monetary resources, and is a finding of the observational data as well (Saastamoinen et al., 2012); the more complex the task, the less there are systems to support the tasks. Byström’s (2002) data does not cover electronic information systems because her data were collected before the mid 1990s and electronic systems were not in use then in the administration of the studied city. Byström's categories of official documents and registers are close enough to be compared with organizational information systems. One may state that official documents are found in the (organizational) information systems nowadays. Byström’s trend is thus similar to that found in this study, especially the use of official documents dropping with increasing task complexity. Registers are used little in all tasks, but their share of all information sources is smaller in the most complex tasks (decision tasks) than in less complex tasks (normal information processing tasks).

Second, we found that growing task complexity indicates enhanced Web use. The Web and organizational information systems seem to be two sides of the same coin. A similar trend was also seen in observational data (Saastamoinen et al., 2012). The features of Byström’s (2002) external literature reflect the features of the modern Web environment. They both are publicly available sources (external literature can be found in libraries, for instance) containing documented information and they cover a larger scale of topics than internal literature or official documents. The information one is seeking for on the Web is not stored in any internal databases because it is seldom needed, for instance. Being a publicly available source also means that the information is not confidential. We can assume that any proprietary documents and/or key information of the organization is only internally available either because of frequent need and usage or because of confidentiality. Overall, the use of literature is minor in Byström's study, but it grows along task complexity. At the same time, the internality of literature drops. In other words, using external literature increases in the same way as the use of the Web in our data. As Byström'sinternal literature is probably provided for frequent use, it seems to relate more strongly to everyday decision making (that is simple tasks) than external literature. The same seems to apply to the differences between our organizational information systems and the Web.

Taken together, it would seem that complex tasks and larger scale ('outside the box') information seeking tend to intertwine. If all information needed is found in internal sources, the task may not be regarded as a complex one after all. Thus the performer may evaluate a task as simple afterwards. If performing a task requires plenty of information seeking, especially from external sources instead, the whole task may become more complex. The cause and effect are closely related especially if the task is information-intensive, that is if information seeking forms a major part of task process.

Third, the use of humans as information sources is generally associated with flexibility. They can understand other humans’ information needs even if they are vague. Our participants expected that they would use human sources more as tasks became more complex. This trend did not materialise. Although human sources have a bigger share in semi-complex and complex tasks than in simple tasks, the peak was in semi-complex tasks. Interestingly, semi-complex tasks have a high number of unexpected human sources; 53.8% of all unexpected, new sources. The corresponding share is only about a third in simple and complex tasks. In other words, human sources were mostly used in semi-complex tasks and the use was raised by many human sources that are only discovered during task performance. In contrast to the finding of the questionnaires, our observational data showed that communication (including e-mail) increases moderately with task complexity (Saastamoinen et al., 2012). The questionnaire data does not support this finding even if we added the use of e-mail to human sources. In other words, our data do not indicate any connections between materialised human source use and task complexity. The interdependence is not clearly curvilinear either, though the peak of use is in semi-complex tasks.

However, it is an obvious trend in Byström’s (2002) study that human source use increases along task complexity. Her diary forms were very similar to our questionnaires. Thus this cannot be only a question of choosing a data collection method. One probable explanation of the relationship between human sources and task complexity is rather uninteresting. It may be that people are not aware how much they tend to communicate with other people while performing their tasks. As outside observers we did not assess the significance or success of telephone calls or unofficial meetings; we just calculated them. Another possibility is that these unsuccessful communicational sessions were not reported in the questionnaires. The reader should remember that these are just speculations that are hard to prove without any analysis that only concentrates on communication, which was beyond our research agenda and research questions. Still, the finding that the two data collection methods give different results points to an intriguing area for future research.

Information sources and information types

We discuss here the connections between information sources and information types. The ways task complexity affects information type use are discussed earlier in Saastamoinen et al. (2013). The participants were asked to name the source and the information expected (task initiation form) and used (task ending form). The questionnaire data demonstrated that connections between information sources and information types exist. The results are still only indicative. Organizational information systems and e-mail proved to provide mainly known items in materialised use, that is, official documents and attached files. Thus organizational information systems and e-mail best supported well defined information needs that are answered with known item searches. Human sources and the Web were used when seeking for information on broader subjects, that is, information aggregates. Thus they support more vague information needs. An important result is that no source type was mainly used for fact finding. However, all sources were used for fact finding quite equally in the case of materialised use, though facts were not the distinct main information type for any source. The linkage between sources and information types is clearer in case of materialised use.

The participants expected that e-mail would provide mainly information aggregates. However, in terms of materialised use, e-mail proved to provide mainly known items. E-mail is the only source that changes focus in this sense. The participants may have first had a more vague idea that they would need some information that can be acquired via e-mail. Then finally it proved to be a specific message or a file that was either needed as such or that happened to fully satisfy the information need. On the other hand, the participants did not expect to use e-mail almost at all when searching for facts, either. In the materialised use, however, a third of e-mail use focuses on facts. The explanation could be similar to the one stated above. E-mail is expected to be useful when information needs are relatively general, but what it actually offers is more restricted information.

Byström (1999) found some indicative information about typical sources of information types. She found that people are used as sources of all kinds of information types whereas official documents and registers are used for obtaining task information and literature for accessing domain information. As already stated above, we can conclude that human sources are more flexible than documentary resources. Our facts and information aggregates are roughly comparable to Byström’s task and domain information. In our data, human sources are expected to offer mainly information aggregates, and some factual information, too. Known items were not expected, reflecting the way the use of human sources materialises. In this respect, our data do not support the assumption that people provide evenly all information types. It seems quite natural that people do not hand known items to each other; known items are sent via e-mail or they can be found in organizational information systems. At least in the organization studied, it seemed that known items - though certainly often produced by humans - were mostly not person-sensitive, such as official documents. In this sense, e-mail was seen as a source rather than the person who passed an agreement, for instance. In contrast, person-sensitive known items could be personal e-mailed messages where the sender rather than the medium was marked as the source.

As we noticed in an earlier section, the use of literature in Byström’s study (1999) can be compared to the use of the Web in our study. They both are able to provide information on larger subjects in addition to a single fact or information needed in a single task. Byström found that registers and official documents provide narrow information which holds true for our (materialised) use of information systems, too. Though information aggregates are expected to be found in organizational information systems, those expectations seldom materialise.

However, all these similarities with Byström’s findings do not reckon with two dissimilar information types that the two studies have. They are task-solving information in Byström’s (1999) data and known items in the present paper. Task-solving information was not recognisable in our questionnaire data. It is also a little more challenging to identify than the other information types. In other words, it relates closely to the actual use of information. Other information types discussed here rather exemplify the richness of information or the potential use of it (narrowly or widely exploitable information).

We conclude our discussion with the following propositions: No single source was heavily relied upon when searching for facts (that is narrowly exploitable information). Organizational information systems were used when searching for known items. Furthermore, people were little used for known item needs – thus people were not perfectly flexible regarding information types. On the other hand, people were the source category most often stated as such, without an explicitly named information type, which may indicate the importance of a human source as a whole. The participants expected that the use of information systems be diverse but this did not quite materialize. E-mail proved to be the most flexible source in the end, which may be explained by its versatility as both a documentary and a human resource.

Data asymmetry

Sometimes either the source or the information was not present in the answers provided by the study participants. For the sake of data symmetry, these cases are included in the present analysis of both the sources and the information types. Cases without a source were omitted from the analyses of pure information source use. Obviously, when some expected sources were missing from the questionnaire replies, they may have been unclear to the participants. That is they did not know beforehand where to seek for the information. Thus these unknown sources inherently differ from sources belonging to the group Other, in which category the source was known and written down, but in the analysis phase it could not be placed in any of the existing categories. This happened to printed books, for example. The categories for other sources and unknown sources are naturally the same in the side of materialised sources. Nonetheless, the interpretation of missing materialised sources (where only an information type is present) is more troublesome. Why did the participants not always report the source though clearly asked and certainly known? Some of these twenty-nine cases were certainly accidents and misunderstandings. For instance, sometimes an information type (as we define them in the present paper) was put both in the box for information source and in the box for the information itself (differently framed, of course) rather than naming a medium as a source. Yet there was not a single case where the box for materialised source would have been left blank intentionally. Bearing in mind that the study was descriptive and the analysis was data-driven, the participants’ replies were not restricted to our understanding of information types and sources. These kinds of mistakes, or rather discrepancies, tell us something about a) the nature of questionnaires as a data collection method; and b) the way participants understand their sources. The latter point is why we wanted to analyse the whole data rather than reduce it substantially by omitting the cases without correct source information in the right box. Certainly, the instructions given to the participants could have been more precise, as well. Using questionnaires leaves the interpretation of concepts to participants.

In conclusion, we argue that a task performer holds back (either consciously or unconsciously) the part that is less important for the information seeking process. This resembles the fact that participants often failed to “remember” all paper sources used (see discussion above). In the task initiation forms, either information type or source was missing, whereas in the task ending forms only a few instances were without an information type. The source was still omitted quite often. Perhaps a person is named as a source without information type because she is needed for many purposes in the same task, even as intellectual support. Thus the person as a source was likely to be more important than any piece of information she could give separately. If an information aggregate was needed, and no information source was reported, perhaps pieces of that information aggregate were found in several places. Or, the source is simply secondary because the need for an information aggregate is overpowering. This results in naming an information type as the source as well.

Conclusions

In this study, we analysed the effects of task complexity on expected and materialised information source use and the connections between information sources and information types. Collecting data on information seeking activities in real work tasks is important relative to both accumulating knowledge and developing better information tools. We should understand information seeking as a process that includes using several sources. Furthermore, these processes are part of tasks that inflict information seeking.

We found that organizational information systems were by far the information source type that was expected to be used the most. This is understandable as the organization studied was the administration of a city; the nature of the organization demands most of the tasks to be routine and at least partly predefined and thus also automated. Thus organizational information systems supported many tasks well. However, organizational information systems were more often abandoned during task performance than any other sources.

The materialised use of organizational information systems followed participants’ expectations in the sense that it was the most popular information source type. Human sources were the second most popular source but they were used one half less, so information systems were quite overwhelming in popularity. However, people were the source category that included the most new, unexpected sources, and here organizational information systems came in second.

Our results indicate that task complexity affects the use of some sources more than others. We found that higher task complexity is connected to increasing expected use of human sources and materialised use of the Web, whereas organizational information systems are expected to be used and finally used less when tasks become more complex. Concurrently, the Web’s share of all new, unexpected sources increases and its share of dropped sources decreases with growing task complexity. Also the dropped Web sources’ share of expected Web sources decreases with growing task complexity whereas the dropped organizational systems’ share of expected organizational information systems increases with growing task complexity. Further, the materialised use of e-mail stays surprisingly constant throughout task complexity categories.

None of the sources were expected to be used nor used mainly for fact finding. The study participants expected that they would mainly be looking for known items when using organizational information systems. Within all other source types, information aggregates were the information type they expected to be needed most frequently. The situation changes a little in materialised use, as e-mail is actually used when searching for known items, not information aggregates.

Our results add to the still shallow knowledge on task based information seeking activities in real life environments. A similar study was conducted in the 1990s (Byström, 2002) and thus also historical contrasting is possible. Further, we collected different kinds of data through observation (Saastamoinen et al., 2012) and questionnaires (reported here and in Saastamoinen et al. (2013). This enables fruitful, empirical comparison between data collection methods.

However, a single study, bound to its temporal and spatial limitations, cannot reveal all aspects of the studied phenomena. The main limitation in our study was the relatively small data set and the challenges it posed to the analysis and interpretation. Our indicative findings need to be tested again, preferably in organizations that differ from local government, for example a business environment. It is important to examine whether tasks of similar complexity induce similar information seeking behaviour across different professional contexts.

Acknowledgements

This research was partly supported by the Academy of Finland (project number 133021).

About the authors

Miamaria Saastamoinen is a postgraduate student and researcher in information studies at the School of Information Sciences, University of Tampere, Finland. Her main research interest is task-based information searching. She can be contacted at: miamaria.saastamoinen@uta.fi

Sanna Kumpulainen holds a PhD in information studies and interactive media from University of Tampere, Finland. Her research interests include task-based information access in the 'wild'. She is currently a university teacher at University of Tampere. She can be contacted at sanna.kumpulainen@uta.fi.