Validation of the visitor and resident framework in an e-book setting

Hazel C. Engelsmann, Elke Greifeneder, Nikoline D. Lauridsen and Anja G. Nielsen

Royal School of Library and Information Science, University of Copenhagen

Birketing 6, 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark

Introduction

Developing and validating new theories is at the heart of every science. A relatively new theory in information behaviour research is the visitor and residents framework (hereafter, generally, 'the framework') (Connaway, Lanclos and Hood, 2013), which was developed as an answer to the digital natives and digital immigrants theory (Prensky 2001a). The visitor and resident framework suggests that context and motivation are of more significance than age or skills, in regards to user's digital behaviour. The framework suggests two behaviour categories, visitors and residents, dependent on digital literacy (Connaway et al. 2013). The aim of this paper is to apply the framework in a new setting and to examine its validity. Instead of focusing on general Internet use behaviour, the study applies the framework to users' e-book use.

From December 2011 to November 2012 the number of adult Americans reading e-books increased from 16% to 23% (Rainie, Zickuhr, Purcell, Madden and Brenner, 2012). While it was only a handful in the beginning, the number of e-books in university library catalogues is now increasing every year (Lamothe 2013) and academic libraries are generally putting more effort in, and spending more money on, e-resources. But these are not used or are not used to their full intent.

By applying the visitor and resident framework on e-book use, this paper explores whether the concepts of a resident and a visitor can help to explain e-book use behaviour, and can help to gain a better insight into users' motivations for e-book use or non-use. Data for validation of the framework came from a questionnaire survey conducted earlier in 2013 by library staff, to determine users' perceptions of the library's e-book services (referred to as the CULIS Soc e-book survey), and from interviews by the researchers with users of the Social Science Faculty Library, which is a faculty library at the University of Copenhagen in collaboration with the Danish Royal Library. The follow-up, qualitative interviews were conducted to further explore users' behaviour and motivations towards e-book use. The interview questions were based on the visitor and resident framework.

Background

Users have problems finding, accessing and reading e-books. The following literature review outlines some main concerns and obstacles to e-book adoption and acceptance. Survey results from vendors (Springer 2008, Springer 2010, Ebrary Global 2011 and Ebrary UK 2012), combined with results from the CULIS Soc e-book questionnaire survey made at the Social Science Faculty Library in 2013 are presented.

E-book use and awareness

Academic libraries have difficulty in making users aware of their e-services (Kennedy, 2011, Lonsdale and Armstrong. 2010, Cole. Graves and Cipkowski, 2010). E-books are often promoted along with other e-resources, but are not visible enough (Vasileiou and Rowley 2011). Courses in information literacy may help in locating and using e-books, and results from the UK Ebrary study (2012) were promising in that regards, because they stated that 24.2% of participants would find e-books more attractive, if they had better training and instruction and 49.2% rated instruction or training as very important.

It is not surprising that a recurring theme in the e-book literature is user's struggle to find relevant e-books. A large percentage of users are aware of the concept of e-books, but some still refrain from using them (Slater 2010). In the survey from Springer (2010) 87% of the participants were aware of the service, and in the CULIS Soc e-book survey 74% indicated that they know e-books. This means that still today about a fifth of all library users are unaware of e-books. Of the users who are aware of the services, 11% have never used an e-book (Springer 2008) or respectively in the CULIS Soc e-book survey 19% have never used an e-book. Being unable to locate e-books was named as one main reason for not using them (Ebrary UK 2012).

Most of these problems are solvable. Better marketing of e-books, an integration of e-books into the catalogue or more training in how to find and use e-books are manageable tasks (Lamothe 2013; Connaway et al. 2013). The sales numbers from Amazon.com clearly show that if e-books are available and easy to download and easy to read on a device, users will indeed use e-books. Already in 2012, for every 100 print books sold through the Website, Amazon.com said it sold 114 titles for its Kindle e-reader device (BBC News Technology 2012). Making popular titles available both as e-books and as printed books is one current approach that aims at inviting more students to pick the e-book version and then get used to reading e-books (Vasileiou and Rowley 2011). Patron-driven-acquisition, a model where the library only purchases digital materials upon a user's request, gives access to a broader selection without buying in advance. It means that the user helps building the e-book collection (Fischer, Wright, Clatanoff, Barton and Shreeves, 2012).

E-book access and adoption

Access and ease of use are further issues that are frequently stated in the research reviewed below. Users should not need to be technical experts to be able to use e-books, but a fifth of the participants in the UK Ebrary survey (2012) found e-books to be difficult to access remotely. Different hard and soft restrictions make the user experience differ from e-book to e-book. Hard restrictions are those that prevent certain actions, while soft restrictions just make these actions difficult, but not impossible. An example of the latter is to not show a print button on the interface, when printing could be effected (on a Windows machine) by pressing CTRL+P (Eschenfelder 2008). If consistency in the way e-books can be used is lacking, users will become frustrated (Slater, 2010).

Some of the digital rights management restrictions disable the natural advantages of e-books: if a restriction makes it impossible to download and share e-books between mobile devices, the mobility of the e-book, an advantage of the digital format, is lost (Walters 2014). Different vendors have different ways of enforcing these rights and users can feel frustrated by the lack of transparency. These issues about licenses might be resolved over time when more e-books are available and both publishers and libraries will probably use e-books.

If users have found an e-book and were able to overcome all technical barriers accessing it, reading it on the screen is another challenge they face. Shelburne (2009) states that 33% of her survey participants saw screen reading as a core problem of e-book use. In the questionnaire survey on e-book perceptions conducted by library staff at the Social Science Faculty Library only 8% read e-books on an e-book reader, while 83% used their laptop or desktop computer. These obstacles might be irrelevant in a year or two. The latest predictions (Anderson 2013) suggest that the bestselling smartphones in 2014 will be available for less than $100 and that the bestselling e-book readers will be at the same price level, if not cheaper. At the same time, a new smartphone (heise.de 2013) was released in December 2013, which has two interfaces incorporated: a normal screen interface and an ink-paper interface for better reading quality. It is thus predictable that - if not all - at least a large portion of academic library users will have the technology to comfortably read e-books in the next couple of years. This could be an interesting development if it will also be transferred to other devices like tablets and computers.

If the issues in user experience can also be unravelled, then the expectation could be that library users will heavily rely on e-books in the near future. Yet, if user needs and motivations for e-book use do not change, then the prediction fails. Thus, this paper looks at academic library users and their motivation for e-books use.

Theory

The basis for this investigation is the visitor and resident framework, which is a follow-up on Prensky's theory of digital natives and digital immigrants (2001b). Prensky describes the digital natives as members of a generation that grew up in a different environment than their parents. According to Prensky, the digital natives spend more time playing videogames and watching TV than reading books. He argues that the digital natives have learned the digital way of thinking from birth, and compares this with speaking one's mother tongue. The older generations have to learn this language as a second language, and as a result they always will have an accent. Prensky illustrates this accent by stating that digital immigrants print out e mails or call people into their office to see a funny Webpage instead of sending a link (Prensky 2001a).

Prensky's theory received a lot of attention, but it also received much criticism (Bennett, Maton and 2008; Margaryan and Littlejohn 2008). The two major criticisms are that a) the Internet has changed considerably since 2001 (Prensky's article was published before the invention of Facebook) and that the predictions of how people will behave did not come true (Bennett et al. 2008); b) the hard divide between being either native or immigrant is an unjustified claim and that research has shown that older people can have a higher digital literacy than younger people and that not all young people are automatically equally native in a digital environment (White and Le Cornu, 2011).

White and Le Cornu argue that the rise of social media over the last years has had a profound influence on online behaviour. In their understanding, the Internet has changed from being a tool for finding information to being a place that allows people 'to project their personas online as a "digital identity" via text, image and video' (White and Le Cornu, 2011, Section III, para. 1). Hence, their framework uses the metaphors of place and tool to describe users' motivations. The focus of the framework is on motivation and not on age. White and Le Cornu further introduce two types of users: the visitors and the residents. In short, visitors see the Internet as a tool shed where they can pick out the right tool to solve their problem, using the Internet as a mean to obtain their goal. The residents on the other hand, use the Web as a mean in itself, a way to extent their identity, a place to discover and develop themselves. According to White and Le Cornu the difference between a visitor's and a resident's behaviour is that visitors think offline while residents think online, seeing the Web as a community of which they are part (White and Le Cornu, 2011). Visitors and residents can be attributed the following characteristics:

| Visitors | Residents |

|---|---|

|

|

An important difference to Prensky's natives and immigrants theory is that White and Le Cornu abandoned the idea that a user would fit in a single box. Instead, they introduced the concept of a continuum. Their new framework stresses that users are neither only visitors nor only residents, but that most users will probably be in both categories, depending on the situation. Users can have a visitor approach in their work life, but have a strong online identity and thereby a resident approach in their personal life.

The framework aims at mapping Internet use behaviour by placing users in an axis of coordinates with a visitor or a resident approach on the two ends of horizontal axes and personal and institutional on the ends of the vertical axes. The horizontal axis expresses the visitors' and residents' behaviour, dependent on the characteristics displayed, whereas the vertical axis shows the engagement span between personal (private life) and institutional (academic) life (White et al., 2012). User's behaviour can be placed on any point of the continuum between the four poles. The mapping allows visualization of qualitative data and helps to display an engagement landscape on to which the user behaviour can be tabled. At a later stage, the mapping will visualize motivation trends of groups of users (Connaway et al., 2013).

The framework is developed through collection of data in several stages. Phase 1 consisted of semi-structured interviews with participants from United Kingdom and the United States. In phases two and three selected participants contributed diaries of their online behaviour, either by e-mail or video. These diaries were supplemented with follow-up interviews. For the purpose of generalization and comparison, a larger survey is planned for phase four beginning of 2014 (Connaway et al. 2013).

Methods

The data collection took place at the Social Sciences Faculty Library, which is part of the Danish Royal Library. The library was selected because of their emphasis on making room for users instead of just holding a collection of books. Therefore the library has a real need of making students aware of the e-resources, rather than solely on physical books. The library covers anthropology, political science, psychology, economics and sociology. It specialises in serving the social science students enrolled in the university, researchers, professors and other institutions, as well as being a public library.

The research design aimed at having participants with some experience with e-books and thus users were chosen who frequently faced e-books in their research library. The results would have likely looked different at another faculty library, such as for example history, where the use of e-books is much lower. Since the study aimed at understanding how information use took place, participants needed to be exposed to e-books in a higher degree.

The empirical data includes results from both the questionnaire survey conducted by library staff and semi-structured interviews undertaken by the researchers. The qualitative interviews further explored user's behaviour and motivations regarding e-books.

Ten qualitative interviews were conducted, of which six participants were female and four were male. The ages ranged from 21 to 37. Two of the participants were Anglophone (exchange students from Canada and England) and eight were Danish. Nine of the participants were students and one was not. The participants were chosen on the premise that they were patrons of the library and of course by their willingness to participate. All inter-views were conducted in a conference room at the library.

An interview guide ensured that the participants would elaborate on their everyday-life online behaviour and afterwards on their behaviour and attitude towards e-books, leading to an understanding of the participant's behaviour in the interaction with e-books. Questions such as 'Are you always logged on to your Facebook, Mail or Twitter accounts?' aimed at uncovering visitor and resident behaviour as described in the original framework, whereas questions such as 'When you read an e-book, do you use the tools or services available with the e-book technology' or 'Do you download e-books?' uncovered the specific e-book behaviour. This approach set the e-book behaviour into a wider context, as well as gaining insight into their motivation in regards to the particular e-book setting explored.

The annotation software TagPad was used for data collection. The role of interviewer and note taker and observer alternated among the researchers. All participants will be referred to by a pseudonym, and for ease of reading all Danish quotes were translated into English.

Results

The interview questions aimed at uncovering if participants showed a visitor or a resident behaviour in their interaction and use of e-books. The remaining result part of this study is structured as followed: First, a modified version of the visitor and resident framework in an e-book setting is presented and explained using examples from the interviews. Afterwards, core findings of the study are discussed and finally the results of the study are visualised by a mapping of the identified e-book behaviour.

Modified e-book characteristics

Frameworks and models help to understand behaviour. In the present case, the research framework was used as theoretical foundation for data analysis. The central question was whether the framework allows an explanation of e-book use behaviour and if it can help in gaining a better insight into users' motivations for e-book use or non-use. To identify users' behaviour in relation to e-books, a modified version of characteristics based on the visitor and resident concept was developed. The empirical data will continued to be discussed on the basis of this modified model:

| E-book visitors | E-book residents |

|---|---|

|

|

The model is split, like the original, into two groups: one group shows the behavioural characteristics relating to e-book visitor behaviour when dealing with e-books, the other group shows the characteristics related to e-book resident behaviour. E-book visitor behaviour in this revised model covers a behaviour that applies tool shed thinking, e.g., a user will use e-books when a clear benefit is perceived. E-book resident behaviour covers a sense of belonging to a community and an approach to use what is available regardless of the format, that is an e-book resident will do untargeted searches and will use randomly available sources.

E-book visitors and residents

E-book visitors actively make the choice for or against an e-book; they prefer printing out e-books and use them as they would use a printed version by making notes or highlighting by hand. E-book visitors see e-books as a tool to achieve a goal in their personal or institutional life. The questionnaire survey and the interviews show that most participants are e-book visitors, who see e-books primarily as a tool. Some participants used e-books for both personal and institutional purposes and considered them to be a tool in all aspects of life.

This behaviour is recognised in several of the participants' actions, because they choose to print and make notes in the printed text. George found it difficult to read online and saw e-books as something you print from and not something you use and read online:

To the extent possible I try to print the things... I prefer to read on paper rather than on a screen (George, age 23, no. 2)

This thinking offline tendency can be explained by the fact that participants in the interviews rated the tools and services as insufficiently transparent to exploit the advantages of the format.

The e-book visitor's first choice would be the printed version. Typically participants would rather obtain the printed book with the digital version as second choice. Only if the printed option was not available, would they settle for an e-book. Felicity emphasised this by stating:

When you can't get the [printed] book... then sometimes you can choose an e-book... I have used that (Felicity, age 26).

This behaviour was reflected by several other participants in stating that if the goal was to write an assignment they definitely would use e-books as a tool to achieve this goal, but not as the first choice. They were generally interested in foremost finding a title and would deal with the question if it was an e-book or a print version when they got that far. If participants used e-books, it usually meant that the printed version was not available.

In contrast, e-book residents do not make explicit choices for or against a tool, but will use whatever is at hand. They will not necessarily be aware that they are using e-books and do not care what source e-books are from. This attitude was also present among participants when they were looking for some kind of information that could fill their needs and did not notice the format in particular. When asked if they had used an e-book one of them answered:

I am not sure... it's probably both e-books and articles from REX [the library catalogue] and things like that we use? But again it is Facebook that we use, so if someone has found something from the curriculum, that everyone needs, it is [posted], and then I am not sure which channel it comes from (George, age 23, no. 3).

In the questionnaire survey participants were asked to indicate where they had found e-books. Despite the fact that Facebook study groups are quite typical according to the interviews, none of the participants mentioned a digital study group as a place to find e-books. This emphasises that some users show an e-book resident behaviour, because they are not aware of the resources they use.

E-book residents have a high level of interaction with e-books. They live, to use the original framework terminology, in the e-book by reading e-books on tablets and computer screen and by making notes in the e-books:

I think it works well you can underline and write comments (Felicity, age 26, no. 4).

E-book residents feel comfortable in the digital world and in using e-books:

I think I prefer e-books, of course it's nice to have a text in front of you, but I think it's just as easy to have an e-book... I think it's easier than having to carry multiple books with you home and return to the library (Henrietta, age 25, no. 5).

Whenever there is an online version of a book available Henrietta will choose it. However, Henrietta only shows this behaviour in relation to her academic life, because when reading fiction she expressed a need for printed books to get the full enjoyment out of reading.

Core findings

One of the core findings of this research is that Henrietta's behaviour is not unique. Frequently participants showed one type of behaviour in an institutional context and another type in a personal context. For example, Christina,

spend[s] a lot of hours in front of the computer, so it is nice not to, that's why [she] never read[s] online in [her] spare time (Christina, age 25).

On the other hand, some participants opted for an e-book in their private, but not in their institutional life:

And here we borrow them, the children's books, and then we can use the iPad and read them (Beth, age 27, no. 6).

When asked if she uses her iPad to read study related e-books, Beth answered:

No, then I use the computer (Beth, age 27, no. 7).

Beth shows an e-book resident behaviour when she uses her iPad in her private life to read children's books to her daughters. She does not show this behaviour to the same degree in her academic life, as she says that the tools related to academic e-books are not transparent enough. This finding is in agreement with the original framework, which underlines that users can have a visitor approach in their work life, but have a strong online identity and thereby a resident approach in their personal life, or vice versa.

A second core finding is that there were several instances, in which respondent's behaviour could be interpreted as both being an e-book visitor and a resident. The previous quote from George on finding materials through Facebook highlights an e-book resident behaviour that is the use of social media as a facilitator in academic life. Several of the participants used Facebook as a communication tool in study-related matters by sharing texts from the curriculum with fellow students in a Facebook study group. One can argue that these actions show that participants trust the content no matter who uploads it and thus express a strong e-book resident behaviour.

On the other hand, George's quote illustrates the tool-oriented way participants use e-books in relation to Facebook, which qualifies as e-book visitor behaviour. Visitors, as understood in the original framework, are reluctant in their use of social media and do not feel comfortable having a profile or another form of online imprint. All participants in this research had an online persona in form of a Facebook profile, but the participants' attitude towards Facebook differed. Not all of them actively engaged in online discussions, but most of them, like George, used Facebook as a tool for communicating with fellow students in study groups or for work connections. Residents, on the other hand, see the Web as a social place, a community, in which people live. Following the framework, one can argue that if someone is always logged on to social media services, these are an embedded part of people's lives where the distinction between online and offline gets increasingly blurred. Respondent Christina showed a strong resident behaviour by saying that:

if my computer is on, I'll have [Facebook] on (Christina, age 25).

Iris, a respondent who often showed visitor characteristics, felt excluded by the resident behaviour of her fellows:

a lot of our [study-related] work takes place on Facebook... here I am always the last to answer, because I have to start my computer and log on the Internet, which I only do when I am at home or at school, so I won't see it throughout the day (Iris, age 22, no. 8).

The findings showed that indeed some participants did not have a permanent online presence and are more like visitors. But the reason for that behaviour was not always the wish to avoid a permanent presence, but because a person's circumstances did not allow it. Jacob, an exchange student from Canada, stated that he did not:

have a very good phone, no, especially not over here (Jacob, age 21),

which limited his online presence.

Another example of the blurred boundaries between e-book visitor and resident behaviour was Google Books. It was used by participants to browse and get a sense if a certain book held the information they needed. Even though the participants occasionally use Google's version of e-books, they do not recognise it as an e-book, which is apparent when the participants answered 'No' to using e-books, but further on in the interview, talk about using Google's e-book service:

If I am looking into getting a book I'll read like the first couple of things online in Google Books (Jacob, age 21).

The use of Google Books could be considered e-book visitor behaviour, because the service is used as a specific tool. Since the participants imply that they did not consider Google books as e-books, and the fact that they sometimes end up in the e-book by accident, shows that their actions are on the contrary evidence of an e-book resident behaviour.

E-book residents live in the e-book and use it to its full extend. Some participants read e-books on a digital device and also used some of the functions available. However, several of these participants used many functions, but still wrote notes by hand:

I mean things like the highlighting tool is useful... to go back and remember things that are important, but I find that actually I end up writing down [by hand], and that will be what I prefer to do (Christina, age 25).

Even though participants might have a residential behaviour, they sometimes do not access the e-book fully as e-book residents. This offline thinking was a recurrent finding, as the majority of the interview participants would use e-books in an emergency rather than with a particular purpose. The fact that only a few users would live entirely in an e-book corresponds with the questionnaire survey findings regarding reading preference, where only 5% of the participants always preferred to read an e-book over a printed book.

The third core finding is that users' attitudes and motivations might matter much less than contextual factors. Respondents' behaviour might be like an e-book visitor or a resident, but that does not mean that one can make predictions about a user's behaviour in a new situation. For example, the participant Eric had an iPad for a while that he used to search specifically for e-books, but now that he only has a computer he does not see e-books as an option, so he uses printed books again. This means his e-book resident behaviour primarily depended on having an appropriate device. Another example comes from Christina, who states that she prefers printed books, and thus qualifies as an e-book visitor. Yet, she used e-books to acquire course literature and had not used printed books at all during the entire school year due to external circumstances:

No I do not think it is as good as a physical book - [but] it is easier because, in a [study-related] context like this where there is so much to read I can't afford to buy everything (Christina, age 25).

It is the context of the use situation that makes some users behave more like e-book visitors or residents, not necessarily the underlying attitude towards e-books.

Mapping e-book visitor and resident behaviour

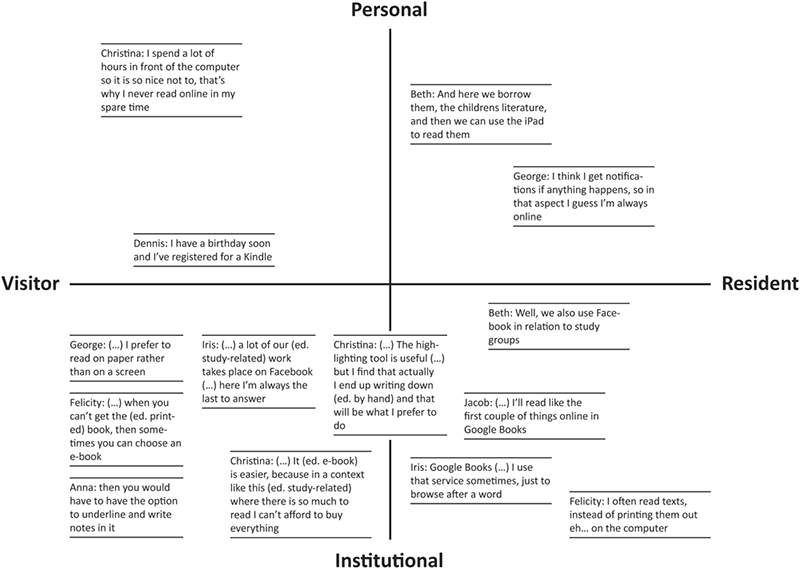

The framework uses mapping to visualize identified behaviour (White et al., 2012). This paper equally illustrates tendencies of user behaviour by plotting quotes describing different degrees of e-book visitor and resident behaviour. The e-book behaviour map uses quotes from the entire sample and not only from individual participants. The quotes used in the map were selected on the basis of identified behaviour throughout the interviews and the questionnaire. The map below illustrates the identified behaviour regarding e-books:

Figure 1: Map of visitor and resident behaviour regarding e-books

The map shows that it is possible to plot the results of the analysis in the framework and that researchers can use the framework to examine e-book behaviour. Yet, the actual plotting was challenging, because in many instances it was unclear whether behaviour was more like a visitor or a resident. In fact, most of the quotations could have been interpreted as either visitor or resident. While the theoretical framework embraces the idea of a continuum where users can be closer or farther away from a pole, it is a weakness that in practice many behaviour instances do not indicate any kind of clear direction. Most participants show a behaviour that has characteristics from both visitors and residents and that is strongly influenced by context.

Conclusion

This research explored if a) the visitor and resident framework can be applied to an e-book context in an academic setting, and b) if the concepts of an e-book visitor or resident can help to explain e-book use behaviour and thus can help to gain a better insight into users' motivations of e-book use or non-use. The first question can be answered without hesitation: yes, the framework can be applied to an e-book context and yes, it was possible to plot participants' behaviour into the framework map.

The answer to the second question is more ambiguous. By using the framework to develop questions for the interviews, it was possible to investigate users' behaviour in a new light and to understand better some of the difficulties users meet when they interact with e-books. The results show that social media were widely used to connect and collaborate in an academic context. Libraries should promote e-books in these circles in order to catch the students where they are comfortable as residents, and perhaps in the same instance give guidance on how to use the tools in the individual e-book. Also they should view users as the complex human beings they are where e-book use is not a yes/no question but depends on how users act in their online life as a whole.

Many behaviour instances could not be interpreted as either e-book visitor or resident. Respondents showed characteristics for both types in the same behaviour situation. If participants' e-book behaviour does not indicate any direction, it is difficult to use the framework to explain behaviour. And that might be the actual result of the mapping: the difficulty of clearly positioning people indicates that people's e-book behaviour is not just one or two types of behaviour. E-book use is just as complex as any other human information behaviour and should receive the same attention.

Without doubt, the framework can help to explain e-book use behaviour, but it is unclear how much it can be used to predic More than once, a respondent acted like a visitor, because of external circumstances and not out of a personal motivation. This research hypothesized that if the issues mentioned in the background section on access, user experience or a better marketing could be unravelled, the expectation would be that library users would rely more heavily on e-books in the near future; that is assuming that user's needs and motivations toward e-book use are not fundamentally against e-books. The results showed that the motivations towards e-book use are less inflexible than expected, and that motivations maybe play a smaller role for e-book adoption than external factors. It is very difficult for libraries to change user's attitudes and motivations. The results show that if libraries would only change some of the external influencing factors, they would not need to worry so much about the motivations.

About the authors

Hazel C. Engelsmann, Nikoline D. Lauridsen and Anja G. Nielsen are Master students at the Royal School of Library and Information Science, University of Copenhagen. Elke Greifeneder is an Assistant Professor in the same university. She holds a PhD from the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany, where she also graduated with a Magister degree in French studies and library and information science.